Historical Ethnobotany and the Need to Study Medicinal

advertisement

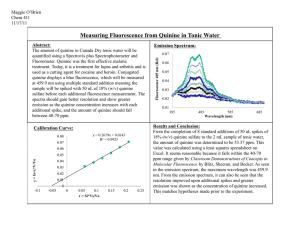

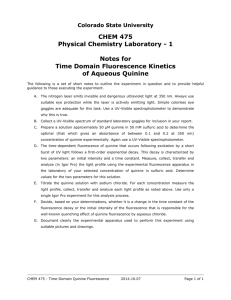

Historical Ethnobotany Hildegard of Bingen 1098 - 1179 Joseph Smith 1805 - 1844 Fertile Crescent King Assurbanipal – 668-626 BCE In his garden with Queen and Servants Babylonian Medicine Datura stramonium Cannabis sativa Mandrake – Atropa mandragora Mandrake – Atropa mandragora ca. 1474 Water lily – Nymphaea alba Vitis vinifera var. Pinot Noir Opium poppy – Papaver somniferum Ergot – Claviceps purpurea Fly agaric – Amanita muscaria Amanita muscaria ornaments? Sumerian Headdress Sun god Horus and Tuth-Shena Urgent need to study medicinal plants 1. To rescue knowledge in imminent danger of being lost Inventory by WHO found 20,000 plant species in use for medicine in 90 countries Only 250 of those species are commonly used or have been checked for main active chemical compounds Urgent need to study medicinal plants 2. The utility of plants in current therapy There has been a rush to develop synthetic medicines based on plant medicines, but often the synthetic medicines don’t work as well as the original plant medicines. For example – quinine and malaria Efficacy of Quinine • Quinine is traditional and effective preventative of malaria • Synthetic preventatives such as chloroquine, maloprim, and fansidar have largely replaced the use of quinine • Many strains of Plasmodium have developed resistances to the synthetics and the synthetics are more toxic. It is recommended that people do not take fansidar for more than 3 months due to potential liver damage. Malaria Cycle Anopheles freeborni mosquito – intermediate host and vector for Plasmodium sp. Historical distribution of Malaria Red areas show countries with malaria today One of the sources of Quinine – Cinchona succirubra Cinchona pubescens Timeline of Quinine Use • 1633, a Jesuit priest named Father Calancha described how to use quinine bark to cure fevers • 1645 Father Bartolome Tafur took some bark to Rome and many of the clergy used it • Cardinal John de Lugo wrote a pamphlet to be distributed with the bark - use of the bark became so widespread that in the papal conclave of 1655 no one died of malaria • 1654 – English aware of use of quinine bark • 1735, a French botanist named Joseph de Jussieu journeyed to South America and found and described the tree that is the source of the bark - he sent samples to Sweden where in 1739, Carl Linneaus named the tree genus Cinchona Timeline of Quinine Use • 20 to 40 species of Cinchona - the species are very hard to tell apart and the species will hybridize, so the exact number of species is unknown – mostly understorey trees • 1820 the French chemists Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Caventou isolated the alkaloid quinine from the bark and identified it was the active ingredient in Peruvian bark • 1861, an Australian named Charles Ledger obtained seeds from an Aymara Indian named Manuel Incra • by 1930, the Dutch orchards in Java produced 22 million pounds of quinine, 97% of the world’s market Chemical structure of quinine Properties of Quinine • Quinine itself is an odorless white powder with an extremely bitter taste • It can be used to treat cardiac arrhythmias as well as malaria - it is also used as a flavoring agent • Quinine prevents malaria by suppressing reproduction of the Plasmodium and also helps prevent some of the fevers and pain associated with malaria Quinine fluoresces under UV light Raymond Fosberg in the field in 1948 Cinchona bark drying in the sun in Ecuador, 1944 Turriabla, Costa Rica agricultural center Urgent need to study medicinal plants 3. To find new molecular models in plants Many times we can take a plant chemical and modify it or make synthetic copies of it that are very valuable to us. Lippia dulcis – sweetener from Pre-Columbian America Hernandulcin Lippia as a sweetener • In Pre-Columbian America, several plants of the genus Lippia were used as sweeteners. (F. Verbenaceae – the verbenas). • In the 20th century, L. dulcis was chemically analyzed and a new sweetener was found, hernandulcin, that is 800 to 1000 times sweeter than sucrose. Urgent need to study medicinal plants 4. The wide use of plants in folk medicine One positive aspect of the use of medicinal plants is their low cost compared to the high price of new synthetic drugs that are totally inaccessible to the vast majority of the world’s people. Another benefit is that most medicinal plants don’t have the kinds of harmful side effects seen with synthetic drugs. Diospyros lycioides – source of chewing sticks in Namibia Ceanothus americanus – Native American chewing stick Modern Chewing Sticks • Most chewing stick plants have a wide range of antibacterial activity against a number of odontopathic bacterial species, and many also contained healing and/or analgesic compounds Bloodroot – Sanguinaria canadensis Rhizome of Bloodroot Bloodroot extracts to treat dental plaque • Bloodroot extracts have been identified as potentially valuable in controlling plaque • Blood root has many alkaloids, known as sanguinaria alkaloids, and sanguinarine in particular, is thought to be a potential problem limiting the usefulness of blood root as a dental medicine • There is an indication that sanguinarine may provoke glaucoma in predisposed humans and cats.