2.4 Consumer Behaviour & Holidays

advertisement

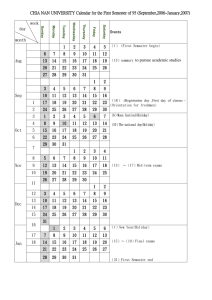

Business Pod 2.4 Consumer Behaviour & Holidays At the core of all business activities is the concept of understanding consumers. Businesses and other organisations look to understand how consumers think, feel, react and make choices, trying to match what they do to how their customers/consumers behave. A large part of this understanding is centred on how consumers reach their buying decisions, often referred to as Buyer Behaviour. A number of models have evolved over the years to map out this behaviour, usually as a linear model eg the Consumer Buying Decision Process originally identified by Engel, Kollat and Blackwell. The problem that you are considering in this assessment is whether the traditional linear model applies to the purchase of a holiday. You look at some of the theoretical approaches in this area and apply them to the purchase of holidays. Learning Objectives The project will help you: To describe a range of theories related to consumer buyer behaviour and their role in analysing markets To appraise your own and others’ motivation in the light of a range of purchase situations The Task Read the case study and answer the questions set at the end. Each question has a word allocation of up to 400 words, making a total of 1200 words for your submission. Assignment 2.4 Page 1 of 10 Business Pod What We Are Looking For To pass this assessment you MUST include the following information: Answers that separately address each of the three questions, using essay format Accurate and complete referencing. Material from the case study and the FCB grid should be referenced T o achieve a higher grade in this assessment you SHOULD clearly demonstrate that you have: An ability to go beyond simply re-stating what is presented in the case. In particular you should avoid repeating at length the individual cases set out in the case A good understanding of popular consumer behaviour theories including the Consumer Buying Decision Process and the FCB Grid Sensible and logical application of these theories in your responses An ability to analyse how consumers buy holidays. Analysis means to use theory to help you explain why something happens as it does. To achieve a grade at the highest level you COULD: Move well beyond the examples in the case study, recognising that they are not necessarily representative of all holiday purchasing and providing your own alternative evidence from the literature For question three, provide sensible and pragmatic advice clearly linked to your findings Resources You have the following help available: Lecture slides and your notes from the consumer behaviour lecture in Phase 2 Week 4. The chapter on consumer behaviour in the textbook (Volume One, p399) The additional notes provided with this case Lecture slides on referencing Material on referencing in the Referencing folder on BREO. Feedback on how you tackled 2.1 Competitive Pricing Strategies and other previous assessments Assignment 2.4 Page 2 of 10 Business Pod Submission Details Remember that we have now covered referencing and plagiarism in detail so you need to meet the rules on this (and all future assignments). Feedback Feedback will be provided by Friday 28th February 2014. You will find your feedback linked to your Turnitin document. Mitigating Circumstances If you are going to have difficulty submitting this assessment on time due to exceptional circumstances you should contact the Student Engagement Team as soon as possible. You can phone them on 01582 489622 or visit the team in the Campus Centre Level 2. Alternatively you can complete an online application for mitigating circumstances at: http://www.beds.ac.uk/studentlife/student-support/academic/extenuating Assignment 2.4 Page 3 of 10 Business Pod Decision-making: an adaptable and opportunistic ongoing process Adapted from a case study by Alain Decrop, University of Maumur, Belgium in Consumer Behaviour A European Perspective (2006) by Michael Solomon, Gary Bamossy, Soren Askegaard and Margaret K Hogg, FT Prentice Hall. Traditional Views Consumers have traditionally been portrayed as rational and risk averse in their purchase decision making. As a consequence, consumer decision-making has been presented from a problem-solving or information processing perspective. Models such as the Consumer Buying Decision Process and the FCB Grid start from the assumption that any consumer need or desire creates a problem within the individual. The consumer undertakes to solve that problem by deciding a course of action in order to satisfy this need or desire. An alternative view has seen consumers’ decision-making as a hierarchy of cognitive, affective and behavioural responses (ie the C-A-B sequence). Within the context of these two main approaches, existing models of holiday decision-making have seen it as: and a rational process implying high involvement, high risk perception, extensive problem-solving information search and a sequential evolution of plans which starts from the generic decision to go on holiday. Study of Holiday Decision-Making The objective of this case is to show how consumer decision-making – within the context of going on holiday – may vary from these traditional models. We followed the holiday decision-making process of 27 Belgian households (single, couples, families and groups of friends) over the course of a year. They were interviewed in-depth four times: three times before their summer holiday and once after it. Many interesting findings emerged which challenged traditional ways of understanding consumer decision-making. Holiday Decision-Making Process Assignment 2.4 Page 4 of 10 Business Pod Holiday decision-making proved to be an ongoing process which was not necessarily characterised by fixed sequential stages, and which did not stop once a decision had been made. Firstly, the generic decision about whether or not to go on holiday was not always the starting point: and sometimes this generic decision was irrelevant (for instance, in the case of regular holidaymakers). For example, a young family had two possible holiday plans. They had already decided on transportation (car), accommodation (camping), activities (beach and visits), and organisation (independently). However, in April they still did not know whether or not they would go on holiday: Anne (F, 41, family): “Actually, it’s not up to us to decide. There are administrative factors that stand in the way at the moment, and it is clear that if we’re looking for a job, and he [her husband] finds a job starting on June 15th, it’s not entirely appropriate to ask for holidays for the entire month of August! It would be a bit stupid to refuse a job on the grounds that you cannot go away on vacation this year. It is the second year running where we do not have control over anything!” Secondly, there is seldom a linear (ie sequential and hierarchical) evolution of holiday plans. Situational factors as well as levels of involvement are responsible for many deviations and changes of mind. Daydreaming, nostalgia and anticipation are other important influences. Thirdly, final decisions and bookings are often made very late. There are a number of reasons for this eg risk reduction, expectancy (situational variables), availability (opportunism), loyalty and personality. Finally, informants often expressed cognitive dissonance or post-decision regret, which they strove to reduce. Information Search for Holidays In the same way, information search is not always a well-defined stage in the holiday decision-making process. Information collection tends to be ongoing, and it does not stop when the holiday has been booked. Substantial amounts of information are gathered during and/or just after the holiday experience. Cognitive dissonance and prolonged involvement are the major explanations for this. Moreover, information search is much less intensive and purposive than is usually assumed. A majority of holidaymakers could be described as low information searchers: they do not prepare their trip in much detail nor for a long time beforehand, rather they prefer serendipitous discoveries and the unexpected. When they were asked about whether or not they had already collected a lot of information about their forthcoming holiday in Tenerife in June, Vincent replied on behalf of a group of friends: Vincent (M, 26, friend party): “No, it’s on the spot. That’s better unplanned, to decide on the day: ‘we’ll go and visit this, we’ll go and visit that’. It’s…Planning everything in advance is a bit annoying.” Assignment 2.4 Page 5 of 10 Business Pod Interviewer: “So you prefer the unexpected and to organise everything once you arrive?” Vincent: “Yes, it’s better…to say already, to see the images and everything. When you arrive, you no longer see it in the same way. You pass it by and you do not even inquire about it because you have read about it, you are…It’s better to go without having seen anything. You go, you discover and you’re more amazed because you’re discovering that…” Searching for holiday information tends to be memory-based (internal) rather than stimulus-based (external). Information is often collected accidentally and passively. Moreover, when information is collected it is not always used and/or sometimes it is put aside for later on. Finally, information collection is a weak predictor of actual choice but rather indicates preferences. Of course, the extent of information collection depends on the holidaymaker’s levels of involvement and risk aversion. Informants found it difficult to say when they started thinking about their current holiday project(s). “Ever since our last holiday ended” was a typical answer. This is another indication that holiday decision-making is an ongoing circular process: as one holiday ends, then planning starts for the next one. The time during and just after a holiday is particularly fruitful for nurturing other projects. In fact, it appears that most holidaymakers are involved in a number of holiday plans all at the same time. These involve different time horizons, different types of decision-making processes. In general, holiday decision-making seems to be adaptable and opportunistic. Incidental learning seems to play a bigger role than intentional learning. This is different from most existing models which assume the existence of a rational, problem-solving holidaymaker. Holiday decision-making often takes account of contextual contingencies, and is triggered off incidentally through information collection or opportunities: Daniele (F, 44, family): “Sometimes, we still want to go somewhere, and then the opportunity arises. Our parents tell us ‘Oh, we are going to Spain, would you like to join us?’ and we say ‘why not?’ and off we go. The times when we have gone away with Intersoc as monitors, it was also because your brother-inlaw said: ’you really don’t want to go? You know, I need leaders…’ And that’s how it was decided! Six months earlier we wouldn’t have known we were going there.” Assignment 2.4 Page 6 of 10 Business Pod Making the Decision about a Holiday Adaptability and opportunism are even more obvious when looking at holidaymakers’ decision strategies. Overall, these strategies are adapted according to the situation and, more particularly, to the type of decision-making unit in which they are involved. The decision-making process tends to be constructed on the spot rather than being planned in advance. Moreover, a substantial number of informants did not use any well-defined strategies in making their holiday decisions. Needs and desires were connected with choice solutions just because they were evoked at the same time. Finally, holidaymakers preferred simple decision rules although these might not be accurate. In line with the general properties of choice processes, it seems that holiday-makers decision-making strategies are characterised by a limited amount of processing, selective processing (the amount of processing is not consistent across alternatives or attributes), qualitative rather than quantitative reasoning, attribute-based and non-compensatory rules (as contrasted with alternative-based and compensatory), and the lack of an overall evaluation for each alternative. Emotions or Plans? Findings further indicate that emotional factors are particularly powerful in shaping holiday choices. Sometimes, people make their holiday decisions according to momentary moods or emotions. The sudden and unforeseen nature of choices is highlighted: a person chooses according to a sudden impulse or falling in love with a holiday idea. This suggests that the affective (emotional) choice mode is more relevant than the traditional information processing mode as far as a highly experimental product such as holidays is concerned. This hedonic (pleasure-seeking) and experiential view of consumer behaviour focuses on product usage, and on the hedonic and symbolic dimensions of the product. It is especially relevant for particular categories of products such as novels, plays, sporting events and travel. However, some systematic elements can be detected in holiday decisionmaking. Holiday plans (destinations) move from being dreams (preferences or ideal level) to reality (expectation level) as time elapses. There is a growing commitment to choice. Sometimes, the preferred aspects of a holiday are replaced by second choices or alternative solutions. While holidaymakers tend to be optimistic and idealistic at the outset of their holiday plans, they become more realistic over time. Initially they focus on external factors which make a holiday possible such as their family situation and occupation. Later in the process they consider factors which limit their choices such as time or budget. Another interpretation of this shift from dream to reality is in terms of the FCB grid. The “feel-learn-do” and the “feel-do-learn” sequences appear to be more salient than the traditional “learn-feel-do” model in holiday decision-making. Assignment 2.4 Page 7 of 10 Business Pod Moreover, holiday plans are instrumental (and dynamic) in achieving higherorder (and quite stable) goals. Major goals are satisfaction maximisation (hedonism) and return on investment (utilitarianism). Finally, information accumulates in a natural, non-purposive way from one source to the other without much searching effort. Information collection becomes more important in the very last days just before a booing is made and during the holiday experience. Further, there is a shift from internal to external sources of information and from general (destination) to more specific (practical) information. In conclusion, holiday decision-making is not necessarily as rational and cognitive as it has often been assumed to be. It entails emotions, adaptability and opportunism to a large extent. There is not one process but a plurality of holiday decision-making processes. Questions 1. Compare and contrast the FCB and CBDP models in relation to the purchase of a holiday and indicate which you think is more appropriate. 2. Compare the information search process for a holiday with the search process that consumers might follow for one other product category (eg a household appliance or a perfume). 3. What do you think the implications of your findings would be if you were advising the manager of a holiday company? Assignment 2.4 Page 8 of 10 Business Pod Additional Note to Help You The FCB Grid Think Feel High Involvement Informative (Economic) Learn –Feel – Do Affective (Psychological) Feel – Learn – Do Low Involvement Habitual (Responsive) Do – Learn – Feel Satisfaction (Social) Do – Feel – Learn The FCB grid was developed as a way to help explain why different types of advertising are appropriate for different types of purchases. One axis distinguishes between high and low involvement or the level of significance that a purchase has for a consumer. The other distinguishes between purchases which are made on the basis primarily of thought and rational assessment or of feeling and emotion. Putting those together, you have the following characteristics for each quadrant, with examples of the buying process in terms of Feeling (our attitudes to something), Learning (the information we seek) and Doing (our behaviour). Increasingly, the “feeling” side of the spectrum is influencing more and more of our purchases, even ones positioned on the left of the grid. The Informative quadrant covers significant purchases which consumers spend time researching and finding out about before making the decision. Traditionally, cars and household furniture fall into this category. Assignment 2.4 Page 9 of 10 Business Pod Learn – I find out a lot about this really expensive purchase, comparing the information about features and prices for several different models. Feel – I feel comfortable about the one I’m going to choose. Do – I make my purchase and drive my car. The habitual quadrant covers small purchases we make on a day-to-day basis such as food. Do – I need toothpaste so I buy a pack. Learn – The pack says it protects my teeth. Feel – It leaves my mouth fresh and I feel fine about buying this brand. I’ll buy it again and not bother about thinking about which brand. The affective quadrant is for significant purchases which we make on a more emotional basis such as fashion clothing. They matter to us as expressions of our personality and may be quite expensive but we don’t choose on the basis careful and rational research. Feel – I look at a lot of different ads and packs of perfume and see which one appeals to me most. Which one expresses my personality best? Do – I buy my perfume. Learn – I find out whether I was right. Am I comfortable with this brand? Purchases in the satisfaction quadrant are about self-satisfaction. They are small purchases but emotionally satisfying ones such as chocolate or cigarettes. Do - I buy a new chocolate bar on impulse. Feel – It’s lovely and comforting. Learn – It’s easy to make myself feel good with little treats Which quadrant would traditional theory have suggested for holidays? Which does the case suggest? What does FCB stand for? It’s not a useful aid to remembering the grid but the name of the advertising agency (Foote, Cone and Belding Advertising) which Richard Vaugn worked for when he developed the grid in the 1980’s. Assignment 2.4 Page 10 of 10