Art and Space

advertisement

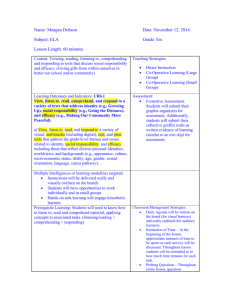

2MED443 Approaches to Media Week Six Art and Space Session Topics The Gallery Space Graffiti and Street Art Graffiti and the City The Gallery Space “The ideal gallery subtracts from the artwork all cues that interfere with the fact that it is ‘art’. The work is isolated from everything that would detract from its own evaluation of itself. This gives the space a presence possessed by other spaces where conventions are preserved through the repetition of a closed system of values” (O’Doherty 1999: 14). The Gallery Space “A gallery is constructed along laws as rigorous as those for building a medieval church. The outside world must not come in, so windows are usually sealed off. Walls are painted white. The ceiling becomes the source of light. The wooden floor is polished so that you click along clinically, or carpeted so that you pad soundlessly, resting the feet while the eyes have at the wall. The art is free, as the saying used to go, ‘to take on its own life.’” (O’Doherty 1999: 15). Graffiti and Street Art By ‘graffiti’, it is generally understood that we mean any form of unofficial or illegal application of a medium onto a surface. ‘Graffiti writing’ is the movement most closely associated with hip hop culture (though it precedes it), whose central concern is the ‘tag’ or signature of the author. Graffiti and Street Art Graffiti writing, particularly tagging or ‘bombing’ points to the idea of destruction as a form of creativity, an ‘anti-art’. Despite all of its destructive tendencies, tagging is a highly aestheticised form of vandalism… …graffiti writers spend years practising and cultivating their personalised alphabets, primarily to write the same word over and over again! Graffiti and Street Art “This new graffiti started to appear on the walls of buildings, at playgrounds, in subway stations, on commercial vehicles, and even inside subway cars. Unpopular with subway riders, beginners’ crude scribbles were helter-skelter, invading the public’s space with what appeared to be no more than vandalism. However, as the writers became more inventive, graffiti developed and matured as quickly as it was produced” (Stewart 2009: 1920). Graffiti and Street Art The ‘aesthetic code’ of graffiti exists in such an internalised language that the main group of people who can fully appreciate it are other graffiti writers. This language that no-one else understands is then used for destroying or defacing cities. Street art and graffiti both have the peculiar ability to exist in the mainstream of culture and at the same time on its margins. Graffiti and Street Art Graffiti writing is an almost always involves ‘tagging’. The majority of street artists, however, are not involved in tagging, even though they may have a pseudonym. Graffiti writing generally revolves around typography and letter formation. This is sometimes combined with figurative elements or ‘characters’. Graffiti characters are generally done with spray paint. Street art embraces a much wider range of media than graffiti, such as stenciling and painting, and breaks with the tradition of the tag. Banksy (2007) Untitled, Bethlehem barrier Graffiti and Street Art “Street art is more about interacting with the audience on the street and the people, the masses. Graffiti isn’t so much about connecting with the masses: it's about connecting with different crews, it's an internal language, it's a secret language. Most graffiti you can't even read, so it's really contained within the culture that understands it and does it. Street art is much more open. It's an open society” (Falie, in Lewisohn 2008: 15). Graffiti and Street Art Graffiti writers can be argued to work in a similar way to major corporations: they reduce themselves to a brand – or ‘tag’ – that comes to have a far greater meaning than the actual word itself. Graffiti writers, through their use of tags, are reducing content down to an absolute minimum. They then expand on this purified form. This is achieved through scale, by enlarging the tag to massive proportions with elaborate designs or ‘pieces’, or through repetition, by placing the tag in as many spaces as possible. Graffiti and the City Both graffiti writing and street art incorporate the urban environment; as such, the city is a space that is ‘claimed’ by the artist. Graffiti takes an anti-modernist position against urban developers and architects. The largely illegal practices of graffiti can be seen to oppose official and corporate culture; the authority manifest in the police, local administration and the train authorities who define graffiti as a form of vandalism. Cultural resistance is signified in the militaristic language of graffiti: writing graffiti is ‘bombing’; a tag is a ‘hit’, and advanced letter formations are ‘burners’. Graffiti and the City “The quality of a hit was the most important thing, followed by the difficulty of accessing the location. However, even if a writer made a particularly difficult hit, his reputation would die out if he failed to produce enough hits. From the start, the primary objective was to get one’s name up in as many places as possible” (Stewart 2009: 31). Graffiti and the City The ideal of modernism was the design of social architecture, such as the productions of the Bauhaus, aiming for the perfect living space in post-war reconstruction. One Bauhaus member, Henri Le Corbusier (1887-1965), became a pioneer in the design of ‘mass production housing’ and urban planning. For Le Corbusier, good modern design should be a rational fusion of new technology and classic ideals: it can have the socially beneficial effect of helping people adapt to the conditions of modern life; a house is a ‘machine for living in’. Unité d'habitation, Marseille, 1947-1952 [example of Bauhaus modernist design, by Henri Le Corbusier] Graffiti and the City In practice, many mass-produced buildings and urban spaces which were developed in accordance with modernist principles translated into ‘concrete jungles’, cheaply made and badly designed housing projects; spaces which suggested exclusion and isolation. Those involved in the graffiti of the 1970s were members of the first generation to grow up in and around this social architecture. The tags and images of those working can be seen as a direct reaction to their architectural surroundings, fighting for a sense of individualism and territory in the face of an everexpanding metropolis; a by-product of a failed rationalist system. Graffiti and the City Graffiti writing in particular was extremely inward-looking, and a major element that developed early on in its history was the complex typographic forms of ‘wild style’ lettering, which were intended to be indecipherable to the general public. Like Pop Art, its images are often drawn from popular culture, such as Fab 5 Freddy’s Campbell’s Soup train (1979), which alludes to Warhol’s own images of Campbell’s Soup tins. This serves to question the corporate ownership of popular cultural signs and images, as well as to undermine traditional ideas about authorship and originality. Andy Warhol (1962) Campbell’s Soup Tins Fab 5 Freddy (1979) Untitled, New York Tracy 168 (1979) The Darkness Surrounds Us, New York Zephyr (2009) Untitled, New York, Lower East Side Graffiti and the City In the early 1970s, individual artists began to work in isolation from crews. Some of the most well-known tags featured numbers at the end of names. These turn the writer’s address into a stylistic accessory. Graffiti has also been examined as a form of abstract anti-representation in urban spaces which are seen as centres of commerce and sources of cultural language and discourse. Graffiti and the City “The city was first and foremost a site for the production and realisation of commodities, a site of industrial concentration and exploitation. Today the city is first and foremost the site of the sign's execution... radical revolt effectively consists in saying ‘I exist, I am so and so, I live on such and such street, I am alive here and now’...” (Baudrillard 1993: 77-78). Graffiti and the City “…SUPERBEE SPIX COLA 139 KOOL GUY CRAZY CROSS 136 means nothing... Such terms are not at all original, they all come from comic strips where they were imprisoned in fiction. They blasted their way out however, so as to burst into reality like a scream, an interjection, an antidiscourse, as the waste of all syntactic, poetic and political development, as the smallest radical element that cannot be caught by any organised discourse” (Baudrillard 1993: 77-78). Graffiti and the City “Hip hop replicates and re-imagines the experiences of urban life and symbolically appropriates urban space through sampling, attitude, dance, style, and sound effects. Talk of subways, crews and posses, urban noise, economic stagnation, static and crossed signals leap out of hip hop lyrics, sounds and themes. Graffiti artists spray-painted murals and (name) 'tags' on trains, trucks and playgrounds, claiming territories and inscribing their otherwise contained identities on public property” (Rose 1993: 22). References Baudrillard, J. (1993) Symbolic Exchange and Death, London: Verso. Lewisohn, C. (2008). Street Art: the Graffiti Revolution, Tate Publishing: London. O’Doherty, B. (1999) Inside the White Cube: the ideology of the gallery space, Berkeley/London: University of Columbia Press. Rose, T. (1993) Black Noise: rap music and black culture in contemporary America, Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. Stewart, J. (2009) Graffiti Kings: New York City mass transit art of the 1970s, New York: Melcher Media. Seminar Questions Spend 5 minutes discussing each question. How important are galleries for giving meaning and value to art? Is graffiti a form of legitimate art or urban vandalism?