Document

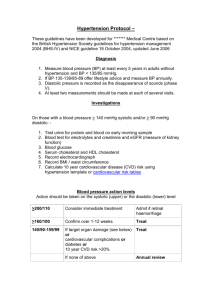

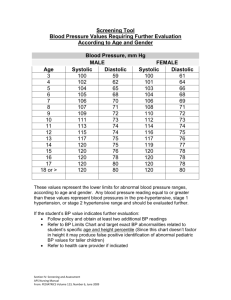

advertisement

Problems in the Elderly Hypertension • hypertension accounts for 35 million office visits per year • slightly >33% of patients with hypertension under control (goal for 2010, 50%) • affects 50 million people in United States • person 55 yr of age with normal blood pressure (BP) at 90% lifetime risk of developing hypertension • higher BP associated with greater risk for myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF), stroke, and kidney disease • in persons 40 to 70 yr of age with BP of 115/75 mm Hg to 185/115 mm Hg, increase of 20 mm Hg in systolic BP (10 mm Hg in diastolic BP) doubles risk for cardiovascular disease (even if still in normal range) BP monitoring • home BP monitoring helpful • 135/85 mm Hg at home correlates with 140/90 in office • ask patients to bring home measuring cuff to office at least once yearly to check for accuracy and correlation with office cuff • Arm cuff more accurate than finger or thumb cuff • Ambulatory BP monitoring—can be helpful for identifying whitecoat hypertension • normal BP, 135/85 mm Hg (120/75 mm Hg when asleep) • results correlate better with end-organ injury, compared to office monitoring • may be difficult to obtain insurance coverage Classification • normal—<120/80 mm Hg • prehypertension— systolic BP 120 to 139 mm Hg, diastolic BP 80 to 89 mm Hg; • stage 1—begin treatment; systolic BP 140 to 159 mm Hg, diastolic BP 90 to 99 mm Hg • stage 2—systolic BP >160 mm Hg, diastolic BP >100 mm Hg • isolated systolic hypertension—common; systolic BP >140 mm Hg, diastolic BP <90 mm Hg • present in most hypertension patients, especially in elderly • widened pulse pressure >50 mm Hg and low diastolic BP (eg, <70 mm Hg) independent cardiovascular risk factors Pathophysiology in elderly patients • increase in arterial stiffness • coincides with increased sympathetic activation (eg, increased adrenaline, norepinephrine, and epinephrine) • larger arteries dilate and thicken, which leads to hyperplasia of intimal layer, increased systolic BP, widened pulse pressure, and greater cardiovascular mortality and morbidity • isolated systolic hypertension is a natural result of aging that causes cardiovascular problems • increased total peripheral vascular resistance • Lowered cardiac output • BP lability (due to changes in baroreceptor function and decreased autoregulation in brain, heart, and kidneys) • in patients 65 to 94 yr of age, average systolic BP 133 mm Hg (±19 mm Hg), diastolic BP 77 mm Hg (±11 mm Hg; prehypertension range) Whitecoat hypertension • occurs in nearly 50% of patients 65 yr of age • diagnosed in patients with hypertension in clinic who have documented accurate BP readings <134/84 mm Hg outside clinic • prognosis in end-organ damage is the same as in normotensive patients • treat patients with other risk factors, and watch symptoms (eg, dizziness) Pseudohypertension • advanced arterial stiffness prevents compression by arm cuff • results in higher BP reading • Osler’s sign—after pumping arm cuff, brachial artery palpable, but no audible beats • intraarterial pressure not reflected by cuff pressure • difficult to reproduce • accurate diagnostic test not currently available Treatment goals • reduce cardiovascular and renal morbidity and mortality • help prevent vascular dementia • focus on systolic BP • goal for patients without diabetes or renal disease, 140/90 mm Hg (130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes or renal disease) • treatment decreases risk for stroke by 35% to 40%, MI by 20% to 25%, and CHF by 50% • 5-yr treatment of 19 elderly patients with isolated systolic hypertension prevented 1 cardiovascular event (number needed to treat [NNT] to prevent 1 cardiovascular death, 50 • NNT to prevent1 all-cause death, 63) • NNT lower in all categories for older patients Treatment goals • how low is too low? • trial looking at patients with mean age 61 yr found best effect of treatment on cardiovascular events with systolic BP 130 to 140 mm Hg and diastolic BP 80 to 85 mm Hg • another study in older patients found lowering systolic BP to <150 mm Hg did not provide further prevention of stroke, and diastolic BP <55 mm Hg showed twice rate of cardiovascular events • systolic BP <130 mm Hg showed increase in cardiovascular events • suggested goals—diastolic BP 90 mm Hg; higher systolic BP possibly acceptable for older age groups Lifestyle modification • • • • • • • • • • • • • • initial treatment of stage 1 hypertension and diabetes weight reduction (level C recommendation clini-cal data lacking) reduction of BP with Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan equivalent to that with monotherapy reduce dietary sodium increase physical activity (level A recommendation) moderate alcohol consumption and cessation of tobacco smoking (level A recommendations) Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) recommends 6-mo trial of lifestyle modification before considering medication paced breathing—some case reports and small nonrandomized trials found deep breathing exercises with device that helps slow breathing reduced systolic BP by 15 mm Hg and diastolic BP by 8 mm Hg over 1 mo one study found paced breathing no better than placebo in patients with type 2 diabetes other studies show good reduction in BP No outcome studies about cardiovascular disease prevention Low risk no side effects expensive ($300-$500) Pharmacologic treatment • • • • • • • • all effective in lowering BP and improving cardiovascular mortality and morbidity Thiazide diuretics—basis of most outcome trials unsurpassed in preventing cardiovascular complications of hypertension; enhance efficacy of multidrug regimens diuretics do not widen pulse pressure in elderly patients Affordable Recommended by JNC 7 as first-line therapy for uncomplicated hypertension; Pharmacologic treatment • can consider angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), calcium channel blocker, combination therapy • Beta-blocker (in certain cases; meta-analysis showed poorer outcomes [especially with atenolol] than with thiazide diuretics) • Can progress in stepwise fashion starting with thiazide diuretic and then moving on to other medications as needed • Can consider starting 2 drugs initially if systolic BP 20 mm Hg and diastolic BP 10 mm Hg above goal • most patients eventually need 2 or more medications Key trials • Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering treatment to prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)—1) compared amlodipine, lisinopril, and doxazosin to chlorthalidone in 42,000 patients with risk factors (eg, diabetes, overweight) • 2) added either atenolol, clonidine, or reserpine • 3) added hydralazine • doxazosin stopped early due to higher incidence of CHF (avoid alpha-blockers unless treating benign prostatic hyperplasia with hypertension) • at 5-yr follow-up, no difference in primary end point of combined fatal coronary heart disease or nonfatal MI, but chlorthalidone better than lisinopril or amlodipine at preventing HF Key trials • Second Australian National Blood Pressure Study (ANBP2)—1) openlabel randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 6000 healthy patients • looked at ACE inhibitor vs diuretic; • 2) added Beta-blocker, alpha-blocker, or calcium channel blocker • primary end point changed at midpoint of study from total cardiovascular events (including death) to all cardiovascular events and all-cause morbidity • primary end point with ACE inhibitors marginally lower (56.1 events vs 59.8 per 1000 patient-years) • stroke rate lower with diuretic • problems with study include change in primary end point, open-label design (may have introduced bias), and use of diuretics in ACE inhibitor group • reanalysis found differences in primary end points almost exclusively attributed to BP control Key trials • Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial–Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA) • 1) open-label RCT compared amlodipine to atenolol in 20,000 patients with 3 cardiovascular risk factors • atenolol least beneficial Beta-blocker for BP control • 2) added perindopril vs thiazide diuretic with potassium, then doxazosin • patients followed for 5.5 yr, trial stopped early • no significant difference in end point between amlodipine and atenolol • reduction in all-cause mortality (secondary end point) slightly better with amlodipine • differences between arms attributed to BP control (ie, BP control, rate of stroke, and cardiovascular mortality better in amlodipine arm) • validity issues include change in statistical significance, use of lipophilic Beta-blocker • (less effective), few patients on Beta-blocker and diuretic, and openlabel design • shows lowering BP helpful Chlorthalidone • At higher doses lowers potassium • lower doses provide good control of BP with less effect on potassium levels • longer acting and more potent diuretic than hydrochlorothiazide • (no head-to-head data [uncertain whether it reduces cardiovascular events]) Treatment trials in elderly • in 12 studies, average drop in systolic BP 17 mm Hg (diastolic BP, 8 mm Hg) with 30% decrease in relative risk for coronary artery disease (CAD), CHF, and overall total cardiovascular diseases • Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) study of chlorthalidone, atenolol, and reserpine in 5000 patients (average age 72 yr) with isolated systolic • hypertension saw BP decrease from 177/77 mm Hg to 143/68 mm Hg (NNT to prevent stroke, 50 • NNT to prevent cardiovascular event, 20) • another trial using calcium channel blocker, ACE inhibitor, and thiazide diuretic saw 25-mm Hg drop in systolic BP (diastolic BP, 8 mm Hg • NNT to prevent stroke, 100; NNT to prevent cardiovascular event, 50) Treatment trials in elderly • Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2 (STOP-2)—looked at • 1) diuretics and Beta-blockers, 2) ACE inhibitors, and 3) calcium channel blockers • no difference between 3 arms in outcome or lowering of BP • Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE) saw no difference in lowering of BP with candesartan (compared to placebo), but nonfatal stroke lower with ARB Treatment trials in elderly • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET)—4000 patients >80 yr of age with low prevalence of diabetes and CAD, and systolic BP >160 mm Hg exclusion criteria included CHF, dementia, and nursing home care; target BP 150/80 mm Hg indapamide (Lozol; nonthiazide diuretic) and perindopril compared to placebo beneficial effects seen within 1 yr Patients treated for 2.1 yr BP lowered by 15 mm Hg decrease in primary end point (stroke) not statistically significant; trial stopped due to statistically significant decreases in stroke deaths (39%) and all-cause deaths (21%) in treatment arm 21% decrease in cardiovascular deaths not statistically significant 64% decrease in CHF highly statistically significant fewer adverse events (ie, side effects) reported in treatment group (statistically significant) conclusions include importance of screening for hypertension in patients >80 yr of age, systolic BP of 160 mm Hg key point for starting treatment, and indapamide and perindopril (ie, thiazide diuretics and ACE inhibitors) effective; other studies using perindopril may indicate inherent quality of drug provides added benefits (eg, protection against repeat stroke) unclear whether results due to BP lowering alone or inherent qualities of indapamide and perindopril ideal systolic BP for patients >80 yr of age, 150 mm Hg (uncertain whether lower better) The DASH Studies Goals (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) • • • • • • • • • Daily Nutrient Goals Used in (for a 2,100 Calorie Eating Plan) Total fat 27% of calories Sodium 2,300 mg* Saturated fat 6% of calories Potassium 4,700 mg Protein 18% of calories Calcium 1,250 mg Carbohydrate 55% of calories Magnesium 500 mg Cholesterol 150 mg Fiber 30 g BOX2 * 1,500 mg sodium was a lower goal tested and found to be even better for lowering blood pressure. • It was particularly effective for middle-aged and older individuals, • African Americans, and those who already had high blood pressure. • g = grams; mg = milligrams Following the DASH Eating Plan • • • • • • • • Grains 6–8 /d1 slice bread1 oz, dry cereal, 1/2 cup cooked rice, pasta, or cereal. Whole grains are recommended for most grain servings as a good source of fiber and nutrients. Vegetables 4–5/d 1 cup raw leafy vegetable, 1/2 cup cut-up raw or cooked vegetable, 1/2 cup vegetable juice Fruits 4–5 /d1 medium fruit, 1/4 cup dried fruit, 1/2 cup fresh, frozen, or canned fruit, 1/2 cup fruit juice Fat-free or low-fat, milk and milk products 2–3/d 1 cup milk or yogurt, 11/2 oz cheese Lean meats, poultry, and fish 6 or less/d 1 oz cooked meats, poultry, or fish, 1 egg Nuts, seeds, and legumes 4–5 per week 1/3 cup or 11/2 oz nuts, 2 Tbsp peanut butter, 2 Tbsp or 1/2 oz seeds, 1/2 cup cooked legumes (dry beans and peas) Fats and oils 2–3/d 1 tsp soft margarine, 1 tsp vegetable oil, 1 Tbsp mayonnaise, 2 Tbsp salad dressing Sweets and added sugars 5 or less per week 1 Tbsp sugar, 1 Tbsp jelly or jam, 1/2 cup sorbet, gelatin, 1 cup lemonade How to Lower Calories on the DASH Eating Plan • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • The DASH eating plan can be adopted to promote weight loss. It is rich in lower-calorie foods, such as fruits and vegetables. You can make it lower in calories by replacing higher calorie foods such as sweets with more fruits and vegetables—and that also will make it easier for you to reach your DASH goals. Here are some examples: To increase fruits— ● Eat a medium apple instead of four shortbread cookies. You’ll save 80 calories. ● Eat 1/4 cup of dried apricots instead of a 2-ounce bag of pork rinds. You’ll save 230 calories. To increase vegetables— ● Have a hamburger that’s 3 ounces of meat instead of 6 ounces. Add a 1/2-cup serving of carrots and a 1/2-cup serving of spinach. You’ll save more than 200 calories. ● Instead of 5 ounces of chicken, have a stir fry with 2 ounces of chicken and 11/2 cups of raw vegetables. Use a small amount of vegetable oil. You'll save 50 calories. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • How to Lower Calories on the DASH Eating Plan To increase fat-free or low-fat milk products— ● Have a 1/2-cup serving of low-fat frozen yogurt instead of a 1/2-cup serving of full-fat ice cream. You’ll save about 70 calories. And don’t forget these calorie-saving tips: ● Use fat-free or low-fat condiments. ● Use half as much vegetable oil, soft or liquid margarine, mayonnaise, or salad dressing, or choose available low-fat or fat-free versions. ● Eat smaller portions—cut back gradually. ● Choose fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products. ● Check the food labels to compare fat content in packaged foods— items marked fat-free or low-fat are not always lower in calories than their regular versions. ● Limit foods with lots of added sugar, such as pies, flavored yogurts, candy bars, ice cream, sherbet, regular soft drinks, and fruit drinks. ● Eat fruits canned in their own juice or in water. ● Add fruit to plain fat-free or low-fat yogurt. ● Snack on fruit, vegetable sticks, unbuttered and unsalted popcorn, or rice cakes. ● Drink water or club soda—zest it up with a wedge of lemon or lime. DASH Diet • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Because it is rich in fruits and vegetables, which are naturally lower in sodium than many other foods, the DASH eating plan makes it easier to consume less salt and sodium. Still, you may want to begin by adopting the DASH eating plan at the level of 2,300 milligrams of sodium per day and then further lower your sodium intake to 1,500 milligrams per day. The DASH eating plan also emphasizes potassium from food, especially fruits and vegetables, to help keep blood pressure levels healthy. A potassium-rich diet may help to reduce elevated or high blood pressure, but be sure to get your potassium from food sources, not from supplements. Many fruits and vegetables, some milk products, and fish are rich sources of potassium. (See box 12 on page 21.) However, fruits and vegetables are rich in the form of potassium (potassium with bicarbonate precursors) that favorably affects acid-base metabolism. This form of potassium may help to reduce risk of kidney stones and bone loss. Follow-up • JNC 7 recommends monthly (or more frequent) visits until good BP control achieved, then follow up every 3 to 6 mo • check potassium and creatinine twice per year • when starting low-dose aspirin, wait until BP under control Choice of medications • • • • • • • • • • • quality of life—difficult to measure discuss with patient no class of medication clearly superior ACE inhibitors and ARBs appear more helpful for dementia and memory with less sexual dysfunction CHF—diuretics; Beta-blockers (eg, carvedilol, bisoprolol, metoprolol start slowly and titrate up slowly) ACE inhibitors and ARBs (level A recommendations) antialdosterone agents effective in patients with metabolic syndrome, and help with remodeling of cardiac tissue post-MI— Beta-blockers standard of care ACE inhibitors (if patient stable and has normal left ventricular function) aldosterone antagonists shown helpful for remodeling after MI Choice of medications • high cardiovascular risk—diuretics and Beta-blockers (level A recommendations) • ACE inhibitors; calcium channel blockers in diabetes—thiazide diuretics can increase patient’s blood glucose (consider indapamide) • Beta-blockers (level B recommendation) may mask hyperglycemia in patients on insulin • ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and calcium channel blockers recommended • chronic kidney disease—combination of ACE inhibitors and ARBs causes side effects, worsening renal function, and no significant improvement in BP • consider direct renin inhibitor (eg, aliskiren) in patients who do not do well on ACE inhibitor or ARB • recurrence of cerebrovascular accidents—prevent by lowering BP • risk reduction with perindopril and indapamide, 43% Improving control • relationship with patient important • Provide treatment and follow-up within context of patient’s cultural beliefs • agree on BP goal • consider costs and complexities of care • once-daily medications ideal for elderly patients • use combination therapy and low-cost medications • focus on widespread and cost-effective care Resistant hypertension • failure to reach goal despite taking 3 drugs • look at identifiable causes • explore reasons with patient • consider higher medication doses or use of loop diuretic in patients with kidney disease • BP may increase due to renal feedback loop (consider increasing or adding diuretic) Pseudohypertension • Pseudohypertension refers to falsely elevated systolic BP readings in elderly patients with very stiff arteries. • Pseudohypertension occurs because the BP cuff cannot completely occlude the artery. • Osler's sign, the ability to palpate the stiff, thickened radial artery when the sphygmomanometric cuff is inflated to suprasystolic BP, was once thought to suggest pseudohypertension, but more recent studies suggest that Osler's sign is an unreliable marker for this condition. • Alternative ways to distinguish true systolic hypertension from pseudohypertension include arm x-rays to document extensive vascular calcification and Doppler flow studies, but neither is routine practice. • More commonly, pseudohypertension is diagnosed when elderly patients do not respond to treatment, have markedly elevated systolic BP without signs of end-organ damage, or develop signs of hypotension (eg, fatigue, orthostasis) despite persistently elevated BP measurements Secondary hypertension • Secondary hypertension should be suspected when BP is resistant to treatment or increases rapidly over weeks to months or to very high levels. • An abdominal bruit over one or both of the renal arteries, especially in a patient with other manifestations of vascular disease, suggests renal artery stenosis. • Hypokalemia unrelated to diuretic therapy and accompanied by metabolic alkalosis suggests primary aldosteronism. • Other tests for secondary causes of hypertension may include polysomnography (for obstructive sleep apnea) • Thyroid examination and thyroid function testing (for hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism), magnetic resonance angiography (for renal artery stenosis • Measurement of 24-h urinary cortisol (for Cushing's syndrome) • Measurement of plasma metanephrine (for pheochromocytoma) • Ratio of plasma aldosterone activity to plasma renin activity (for primary aldosteronism), and abdominal CT (for adrenal tumors associated with primary aldosteronism or pheochromocytoma). Conclusions • controlling systolic BP more important than diastolic BP in patients >50 yr of age • thiazide diuretics mainstay of treatment • tailor treatment recommendations to patient’s medical conditions • lowering BP in patients and populations more important than which agent used Questions and answers • thiazide diuretics and sulfonamide allergy—indapamide recommended (cross-reactivity, 20%- 25%) • consider ACE inhibitor, ARB, or loop diuretic • BP measurements—repeating BP measurement at end of office visit helpful (often 10-15 mm Hg lower) • diuretics and swollen feet—consider chlorthalidone (more potent) • clonidine (eg, Catapres, Duraclon)—useful for hypertensive urgency; systolic BP >240 mm Hg—send patients to emergency department • associated with high risk for stroke • hyponatremia and thiazide diuretics—if mild, no action needed; if more severe (eg, 123 mEq/L with dizziness and confusion), switch agents or consider another class of medications • use low-dose chlorthalidone or indapamide (associated with less sodium loss than thiazide diuretics) Questions and answers • isolated systolic hypertension—ARBs, ACE inhibitors, and thiazide diuretics effective • key to lower BP • small study showed slight decrease in nonfatal stroke with ARBs • thiazide or thiazide-like diuretic recommended (lowers BP without widening pulse pressure) • thiazide diuretics and urinary frequency and urgency— lowering of BP can be obtained with doses as low as 6.25 mg to 12.50 mg with little diuresis • recommend taking in morning • in patients >80 yr of age start at 6.25 mg and do not exceed 25 mg • Antialdosterone agents—can be effective in patients without primary aldosteronism Demographics of the elderly • presently, 13% of population in United States >65 yr of age • for statistical purposes, 65 yr of age used to define elderly • by 2030, 20% of population >65 yr of age • elderly divided into young old (65-75 yr of age), middle old (75-85 yr of age), and old old (>85 yr of age) • old-old group fastest growing segment of population Emergency department (ED) • Emergency department (ED) visits: >15% from elderly • Regional variations present (eg, greater elderly population in Florida) elderly stay 20% longer and undergo more extensive work-up (more laboratory tests and studies), with higher rate of misdiagnosis • poor tolerance of delays in diagnosis • higher rates of morbidity and mortality Coronary artery disease (CAD) • • • • • • • • • • • • leading cause of death in elderly in United States age most powerful predictor 85% of deaths from cardiac disease occur in the elderly population; 30-day mortality after myocardial infarction (MI) significantly increased as patient’s age increases (<65 yr of age, mortality 3% young-old group, 9.5% old-old group, 30%) even higher mortality if MI missed in patients >65 yr of age in elderly patients discharged from ED with MI, mortality 50% within 3 days overall, MI leading cause of malpractice payouts in emergency medicine (20%); major causes for missed diagnosis include failure to consider high-risk groups failure to recognize atypical presentations, overreliance on negative tests Physiologic Changes of Aging • Heart: increased stiffness of aorta results in increased arterial blood pressure and afterload, and left ventricular hypertrophy • (LVH) more common (risk factor for early MI and worse outcome after MI) • delayed or impaired diastolic filling produces atrial stretch, placing elderly at higher risk for atrial fibrillation (AF), including after MI • higher filling pressure leads to development of LVH • after 35 yr of age, cardiac output reduced by 1% per year (reversed by exercise exercise to some extent), Physiologic Changes of Aging • resulting in greater risk for development of congestive heart failure (CHF) with any medical stress • in elderly, sepsis, and sometimes even emotional stress, can produce heart failure (lack ability to compensate) • decreased response to endogenous and exogenous catecholamines • inadequate production of catecholamines, and response from adrenoreceptors poor • poor response to catecholamines may require maximization of dose, with • higher risk for tachycardia and other side effects • most of elderly on Beta-blockers, which mitigate response to epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine, and dobutamine drips • may need to consider nonadrenergic vasopressors when elderly patient in shock • for CHF, consider milrinone if patient not responding • for septic patient, add vasopressin to norepinephrine; Physiologic Changes of Aging • • • • • • • • • • • glucagon—used only in acute overdose of Beta-blockers; significant dose required because of saturation of receptors with -blockers and chronically downregulated adrenoreceptors; main adverse effect vomiting; not as effective in patients with long-term Beta-blocker use shock—develops earlier and more easily elderly unable to compensate for reduced cardiac output (unable to increase heart rate [HR]) instead, rely on increasing ventricular filling and stroke volume (cardiac output equals stroke volume multiplied by HR) most elderly patients dehydrated due to decreased thirst response and renal vasopressin response (unable to hold water) Consider intravenous (IV) fluid bolus in all elderly patients with systemic illness (unless obviously fluid overloaded) Endothelial dysfunction—one of most prominent causes of development of atherosclerosis irritation or dysfunction within endothelium of coronary arteries decreased coronary vasodilatory response, angiogenesis, and collateral vessel formation Kidneys • decreased renal cell mass and drug clearance result in greater risk for drug toxicities • serum creatinine not good marker for renal function • use creatinine clearance instead • elderly patient with creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL actually in mild renal insufficiency, because renal cell mass decreasing, so creatinine should decrease also • normal creatinine for elderly 0.5 to 0.8 mg/dL • creatinine clearance <30 mL/min indicates renal insufficiency and requires reduced dose of any drug cleared through kidneys • drugs include enoxaparin and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors Acute MI • major high-risk groups include elderly, women, and patients with diabetes • OLDCARD—mnemonic for obtaining history of patient presenting with pain • Onset • Location • Duration • Character • what aggravates pain • what relieves pain • activity of patient (doing) when pain started • associated symptoms • whether pain radiates Textbook presentation of unstable angina or acute MI • onset associated with exertion and gradual (over 10-15 min) • location midsternum and left-sided; duration minimum of 10 min to 2 hr • character substernal pressure and tightness • relieved by rest or nitroglycerin • aggravated by exertion • performing exertional activity when pain occurred • associated symptoms include shortness of breath (SOB), nausea, vomiting, and diaphoresis; pain radiating to left side of neck, jaw, and arm • actual presentation different Actual presentation • onset—70% of patients present with abrupt onset of pain • location—chest pain absent in 20% of patients (have abdominal pain instead) • Obtain electrocardiography (ECG) emergently in elderly patient who presents with upper abdominal pain (only symptom in 6% of elderly with MI) • always consider atypical presentations and obtain ECG • duration—few minutes to few hours • if pain momentary or constant for days, unlikely cardiac in origin • crushing pressure sensation seen in 24% of MIs and 30% of unstable angina • may also present as mild ache • sharp stabbing pain also common; Actual presentation • • • • • • • • • • • • • burning pain or indigestion—described in 20% of Mis and 21% of unstable angina “indigestion” has highest predictive value for ruling in MI reflux esophagitis or peptic ulcer disease most common misdiagnosis for missed MI 15% of patients with MIs obtain partial relief and 7% obtain complete relief with antacids 15% report pain as pleuritic or positional, and 15% report worsening with palpation 7% have completely reproducible pain with palpation study found that 6% of patients with acute costochondritis ruled in for MI should consider MI even if pain reproducible with palpation European study of >10,000 patients ruled in for MI found 7% associated with emotional stress, and 8% eating meal when pain occurred associated symptoms—SOB, nausea, vomiting and diaphoresis common studies found diaphoresis most specific of all symptoms patients with chest pain and diaphoresis almost always require admission; Actual presentation • almost 50% of patients with MI complain of increase in belching (probably due to diaphragmatic irritation from inferior MI) • radiation—pain radiating to right side more specific than pain radiating to left side (worse if pain radiates bilaterally); • pain absent in 33% of patients, especially diabetics and elderly • pain absent in two-thirds of patients >85 yr of age on presentation; instead present with anginal equivalent, with SOB most common • SOB most common chief complaint in elderly with acute MI • neurologic presentation (eg, confusion) possible; acute weakness common in old-old patients • in patients >85 yr of age, generalized weakness and malaise extremely common, and physician should obtain ECG • also obtain ECG in patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who presents with episode of exacerbation of COPD (may precipitate cardiac ischemia) Diagnosis • • • • • • • • Electrocardiography more often nondiagnostic in elderly also consider patient risk factors other cardiac problems (eg, left bundle branch block, LVH, Q wave from old MI) that occur more frequently in elderly may interfere with interpretation of ECG elderly less capable of mounting ST elevation non-ST segment elevation MI (non-STEMI) more common than STEMI in elderly computers programmed to read ischemia only if ST elevation >1 mm (nonspecific if <1 mm) Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) • do not treat • routine treatment increases mortality • routine prophylaxis with lidocaine for ventricular tachycardia (VT) decreases in-hospital incidence of ventricular fibrillation arrest but increases in-hospital incidence of asystolic arrest, increasing overall mortality • sustained VT only time to treat ventricular ectopy • sustained VT defined as wide regular QRS complexes, with rate of >120 beats/min • sustained VT defined as run of VT that either causes instability or lasts >30 sec • (if <30 sec, nonsustained VT does not warrant antiarrhythmic treatment) • treatment of condition other than sustained VT increases overall mortality by increasing asystolic death • in nonsustained VT, look for underlying cause (eg, hypoxia, ischemia, electrolyte abnormalities) • consider – Beta-blocker in intermittent VT Management • Polypharmacy • average elderly patient in United States on 7 medications (4-5 prescription medications, 1-2 herbal medications, • and 1-2 over-the-counter medications) • Anticholinergic toxicity common in elderly because of antihistaminic and anticholinergic side effects of medications (cause mental status changes) • impairment of renal and hepatic function, • decrease in lean body mass • increase in adipose tissue seen as individual ages Beta-blockers • no longer recommended in current American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines for acute MI (also not core measure) • routine use of early IV or oral Beta-blockers associated with increased incidence of cardiogenic shock (specific risk factor in patients >70 yr of age) • not indicated in first 24 hr for elderly patients with MI • sinus tachycardia (>110 or 120 beats/min) also risk factor for cardiogenic shock; presence of tachycardia requires more aggressive treatment for ischemia • only indication in acute MI presence of tachydysrhythmia (eg, rapid AF) or intractable hypertension • (higher dose of nitroglycerin first choice) Nitrates • consider possibility of hypotension • (elderly patient most likely hypovolemic) • ask specifically about other drugs patient taking • sildenafil Aspirin • highly effective • elderly patients often underdosed or not dosed • relative benefits greater in elderly, compared to young patients • if patient has ulcer or history of gastrointestinal bleeding, current guidelines still recommend aspirin but given with proton pump inhibitor • if patient develops rash, give diphenhydramine (Benadryl) • Promethazine (Phenergan) if patient develops nausea and vomiting Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents • clopidogrel—not given with thrombolytics if patient >75 yr of age • Current guidelines state insufficient data to suggest any difference in treatment in elderly (also true for glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors) • patient overdosed if given glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor without calculating creatinine clearance • Data show increased bleeding complications when creatinine clearance not calculated • enoxaparin—data show increased bleeding complications and mortality if creatinine clearance not considered • unfractionated heparin—data show increased bleeding and mortality if patient not weighed before dosing • thrombolytics—age not contraindication • overall, greater benefit seen in elderly than in young patients • percutaneous intervention treatment of choice and only effective treatment for elderly patient in cardiogenic shock Resuscitation • give IV fluids because elderly patient usually dehydrated • consider nonadrenergic vasopressors because of poor response to catecholamines treat shock aggressively • lactate rises before changes in vital signs seen in shock • occult shock relatively common in elderly and should consider obtaining lactate level as early indicator consider empiric magnesium because data show elderly patients most commonly hypomagnesemic due to dehydration, kidney dysfunction, and diabetes • beware of postintubation hypotension • 2 major causes include hypovolemia and tension pneumothorax due to decreased lung compliance • use low tidal volumes and lower ventilatory rates to avoid barotrauma • intubation causes increased intrathoracic pressure that decreases venous return and cardiac output • severe hypotension right after intubation common if patient hypovolemic • cardiac arrest—age alone not significant determinant of survival, but comorbidities are Take-home message • should not rely on presence of chest pain for diagnosis • obtain ECG in elderly patients presenting with malaise or shortness of breath • treat aggressively, except with Betablockers • calculate creatinine clearance if giving anticoagulants and weight if giving unfractionated heparin A patient with a blood pressure (BP) reading of 127/87 mm Hg would be classified as having: (A) Normal BP (B) Prehypertension (C) Stage 1 hypertension (D) Isolated diastolic hypertension Answer • (B) Prehypertewernsion Whitecoat hypertension is diagnosed in patients with hypertension measured in the clinic, and documented accurate BP readings of _______ outside of the clinic. (A) <140/90 mm Hg (B) <134/84 mm Hg (C) <134/80 mm Hg (D) <130/84 mm Hg Answer • (B) <134/84 Hg When managing elderly patients with hypertension, treatment should focus more on controlling systolic BP than diastolic BP. (A) True (B) False Answer • (A) True All the following lifestyle modifications are level A recommendations for hypertension, except: (A) Moderate alcohol consumption (B) Tobacco smoking cessation (C) Weight reduction (D) Increased physical activity Answer • (C) Weight reduction The Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure recommends which of the following classes of drugs as first-line therapy for uncomplicated hypertension? (A) Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (B) Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (C) Calcium channel blockers (D) Thiazide diuretics Answer • (D) Thiazide diuretics The Dash Diet can Lower BP by _______ mmHg • • • • • A) 5 mmHg B) 7 mmHg C) 9 mmHg D) 11 mmHg E) 13 mmHg Answer • D) 11 mmHg One antihypertensive Medication can lower blood pressure by • • • • • A) 10 mmHg B) 12 mmHg C) 15 mmHg D) 18 mmHg E) 20 mmHg Answer • C) 15 mmHg What number is the lowest risk for MI, stroke, Heart Disease and renal failure • • • • • A. 115/75 B. 120/80 C. 125/85 D. 130/80 E. 140/90 Answer • A. 115/75 In persons 40 to 70 yr of age with BP of 115/75 mm Hg to 185/115 mm Hg, an increase of ________in systolic BP (________in diastolic BP) doubles your risk for cardiovascular disease • A. 10, 5 • B, 10, 10 • C. 15, 5 • D. 15, 10 • E. 20, 10 Answer • E. 20, 10 A widened pulse pressure of _______and low diastolic BP (eg,_________) are independent cardiovascular risk factors • A. >40 mm Hg and low diastolic BP (eg, <60mm Hg) • B. >50 mm Hg and low diastolic BP (eg, <70 mm Hg) • C. >60 mm Hg and low diastolic BP (eg, <70 mm Hg) • D. >55 mm Hg and low diastolic BP (eg, <65 mm Hg) Answer • B. >50 mm Hg and low diastolic BP (eg, <70 mm Hg) Choose the correct statement about chlorthalidone. (A) High doses increase potassium levels (B) Lower doses do not provide adequate lowering of BP (C) Longer acting and more potent diuretic than hydrochlorothiazide (D) Associated with fewer cardiovascular events than hydrochlorothiazide Answer • (C) Longer acting and more potent diuretic than hydrochlorothiazide Antialdosterone agents • (A) Effective in patients with metabolic syndrome; help with remodeling of cardiac tissue • (B) Standard of care for treating hypertension after myocardial infarction • (C) Can increase blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes • (D) Shown to reduce relative risk for cerebrovascular accidents by 43% Answer • (A) Effective in patients with metabolic syndrome; help with remodeling of cardiac tissue Beta-blockers • (A) Effective in patients with metabolic syndrome; help with remodeling of cardiac tissue • (B) Standard of care for treating hypertension after myocardial infarction • (C) Can increase blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes • (D) Shown to reduce relative risk for cerebrovascular accidents by 43% Answer • (B) Standard of care for treating hypertension after myocardial infarction Thiazide diuretics • (A) Effective in patients with metabolic syndrome; help with remodeling of cardiac tissue • (B) Standard of care for treating hypertension after myocardial infarction • (C) Can increase blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes • (D) Shown to reduce relative risk for cerebrovascular accidents by 43% Answer • (C) Can increase blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes Perindopril and indapamide • (A) Effective in patients with metabolic syndrome; help with remodeling of cardiac tissue • (B) Standard of care for treating hypertension after myocardial infarction • (C) Can increase blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes • (D) Shown to reduce relative risk for cerebrovascular accidents by 43% Answer • (D) Shown to reduce relative risk for cerebrovascular accidents by 43% Antialdosterone agents can be effective for resistant hypertension in patients who do not have primary aldosteronism. (A) True (B) False Answer • (A) True Which of the following factors is the most powerful predictor of coronary artery disease? (A) Sex (B) Age (C) Presence of comorbidities (D) Lifestyle Answer • (B) Age Which of the following is(are) the major cause(s) for missed diagnosis of myocardial infarction (MI)? (A) Failure to consider high-risk groups (B) Failure to recognize atypical presentations (C) Overreliance on negative tests (D) All the above Answer • (D) All the above In individuals >35 yr of age, cardiac output has been shown to decrease by _______ per year. (A) 0.25% (B) 0.5% (C) 1% (D) 2% Answer • (C) 1% Glucagon is used only in _______ overdose of Beta-blockers. (A) Acute (B) Chronic Answer • (A) Acute Which of the following statements are true about the presentation of MI in the elderly? 1. “Indigestion” has highest predictive value for ruling in MI 2. Reflux esophagitis or peptic ulcer disease most common misdiagnosis for missed MI 3. 15% of patients with MI obtain partial relief and 7% obtain complete relief with antacids 4. 7% of patients with MI have completely reproducible pain on palpation (A) 1,3 (B) 2,4 (C) 1,2,3 (D) 1,2,3,4 Answer • 1. “Indigestion” has highest predictive value for ruling in MI • 2. Reflux esophagitis or peptic ulcer disease most common misdiagnosis for missed MI • 3. 15% of patients with MI obtain partial relief and 7% obtain complete relief with antacids • 4. 7% of patients with MI have completely reproducible pain on palpation (D) 1,2,3,4 Of the symptoms associated with MI, studies show that _______ is the most specific, while _______ is the most common. (A) Shortness of breath; diaphoresis (B) Diaphoresis; shortness of breath Answer • (B) Diaphoresis; shortness of breath Electrocardiography should be obtained in an elderly patient who presents with which of the following? (A) Upper abdominal pain (B) Generalized weakness and malaise (C) Episode of exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (D) All the above Answer • (D) All the above Antiarrhythmic treatment is indicated in ventricular tachycardia lasting <30 sec. (A) True (B) False Answer • (B) False Current guidelines for acute MI still recommend aspirin in patients with peptic ulcer disease or history of gastrointestinal bleeding, but it should be given with: (A) Histamine (H)2-receptor antagonists (B) Antacids (C) Proton pump inhibitors (B) Antacids (D) Prostaglandins Answer • (C) Proton pump inhibitors Data show increased bleeding and mortality if creatinine clearance not calculated before administering _______, and if patient’s weight not determined before administering _______. (A) Enoxaparin; unfractionated heparin (B) Unfractionated heparin; enoxaparin Answer • (A) Enoxaparin; unfractionated heparin