Lecture 10 - Plattsburgh State Faculty and Research Web Sites

advertisement

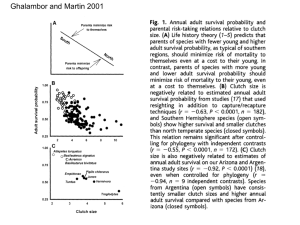

Evolution of parental care Parental care does not always take place. In many species (e.g. clams, barnacles, many fish) eggs are shed into the water and abandoned. Similarly, turtle young are on their own once they hatch Costs and benefits of parental care The decision to offer parental care depends on whether such care will increase the caregiver’s lifetime reproductive success. Greater investment in individual young necessarily reduces the number of young that can be produced. Costs and benefits of parental care Consequently, species choose between producing many, small, uncared for young or fewer, larger, cared for young. Whales and humans represent one end of the continuum and barnacles and clams the other. Costs and benefits of parental care If parental care enhances survival and growth of young enough to compensate for the reduction in young produced then we would expect parental care to evolve. Costs and benefits of parental care Obviously, one constraint of parental care is the ability the parent has to affect the offspring’s survival. Barnacles produce many thousands of eggs which are shed into the water and drift away. They develop into larvae and one day settle permanently on a fixed substrate. Costs and benefits of parental care Barnacles are sessile and can do nothing to actively assist their young. Not surprisingly, barnacles have not evolved parental care. Costs and benefits of parental care Parental care in organisms that can give it may significantly enhance the prospects of the offspring surviving to adulthood. For example, higher bodyweight at fledging significantly increases a small birds chances of surviving to adulthood. Costs and benefits of parental care Extra investment (i.e. the parent’s working harder to supply food) comes at a cost though as it may reduce the parent’s prospects of surviving over the winter. This effect has been documented in many studies in which brood sizes of parents were increased. Costs and benefits of parental care The costs associated with increased investment in a given offspring cause parents to limit the investment they make so as to increase their prospects of survival and also to allow them to invest in future offspring. This decision causes parent offspring conflict. Parent-offspring conflict. In many species parents invest huge quantities of resources in their offspring. Initially, both parent and offspring agree that investment in the offspring is worthwhile because it enhances the offspring’s prospects of survival and reproduction. Parent-offspring conflict. However, a parent shares only 50% of its genes with the offspring and is equally related to all of its offspring, whereas the offspring is 100% related to itself, but only shares 50% of genes with full siblings (and less with half-siblings). Parent-offspring conflict. As a result, at some point, a parent will probably prefer to reserve investment for future offspring rather than investing in the current one, while the current offspring will disagree. When might parent be prepared to sink all its effort into a current offspring? Parent-offspring conflict. This leads to a period of conflict called weaning during which the offspring tries to acquire resources and the parent attempts to withhold them. Parent-offspring conflict. The period of weaning conflict ends when both offspring and parent agree that future investment by the parent would be better directed at future offspring rather than to the current offspring. For full siblings, this is when the benefit to cost ratio drops below ½. Fig 11.18 Figure shows B/C benefit to cost ratio of investing in the current offspring. Benefit is measured in benefit to current offspring and cost is measured in reduction in future offspring. Parent-offspring conflict In instances where parents produce only half siblings, we should expect weaning conflict to last longer because the current offspring is les closely related to future offspring. This has been confirmed in various field studies. Costs and benefits of parental care In general, the willingness of a parent to invest in or take risk for an offspring should be influenced by (i) the parent’s future prospects of reproducing and (ii) the relative value of the current offspring. This is borne out by studies of the behavior of long-lived versus short-lived birds. Costs and benefits of parental care In general, one would predict that longlived birds should be less willing to risk their lives to protect their young, but that short-lived birds should be more willing to do so. Costs and benefits of parental care In general, North American birds are shorter lived than comparable South American species. Ghalambor and Martin (2001) compared the behavior of matched pairs of North and South American birds to evaluate the birds’ willingness to take risks on behalf of their young. Costs and benefits of parental care E.g. compared American Robin to Argentinian Rufous-bellied Thrush. When researchers played tapes of Jays (which raid nests) near the birds’ nests both species avoided returning to the nest, but robins reduced their activity more. Consistent with robins being less willing to risk the current brood. Costs and benefits of parental care When a stuffed Sharp-shinned Hawk (a predator of adults) was placed near the nest and calls played, again both species avoided visiting the nest, but this time the Rufous-bellied Thrushes reduced their visits more. Costs and benefits of parental care These results suggest that the thrushes were less willing to risk their lives by feeding the current brood. Selection on robins and thrushes thus appears to have fine-tuned behavior to take account of costs and benefits of risktaking behavior. Maternal parental care In general maternal parental care is more common than paternal care. In some instances maternal care is a result of internal fertilization and the delay between mating and birth. Fig 12.1A Maternal parental care Other general reasons for maternal care being more common focus on the relative costs to the two sexes of being the caregiver. For males there is uncertainty about paternity, which will reduce the benefit to cost ratio of engaging in parenting. Maternal parental care In addition, for males when there are opportunities to mate with multiple females, males that give up that opportunity to engage in parental care will pay too high a price. Paternal care (either with the female or alone) would be selected for only when the payoff is sufficient to outweigh the costs. Paternal Care In fish male parental care is quite common. Many males mouth brood eggs or care for eggs in nests. Costs of parental care seem to be lower for males than for females. Paternal Care Male sticklebacks can care for 10 clutches of eggs at once. Males grow more slowly when caring for young, but because males are territorial and cannot range widely to look for food the additional cost of parental care is low. Paternal Care For a female stickleback parental care would severely limit her ability to forage and grow. Because body size is closely correlated with egg production loss of foraging opportunities would have a significant effect on future reproduction. Paternal Care Because, in many fish, costs of parental care are higher for females than they are for males, paternal care may have evolved because males lose less from parental care than females do. Discriminating Parental Care Misdirecting parental care towards nonoffspring obviously would be a costly mistake for any organism. Many animals rear their young in colonies and there is plenty of opportunity for confusion. Fig 12.7 Young free-tailed bats at a creche. Discriminating Parental Care Mexican free-tailed bats use vocal and olfactory cues to identify their offspring from among thousands in the creche. The bats do occasionally make mistakes but the benefits of leaving a baby in a creche (mainly thermoregulatory) appear to outweigh the cost. Discriminating Parental Care Cliff swallows, often nest in large colonies, and their young produce much more variable calls than do Barn Swallows, which generally nest solitarily. Cliff Swallow parents are also much better at distinguishing between calls than are Barn Swallows. Fig 12.9 Discriminating Parental Care Similarly, the young of colonial Bank Swallows produce distinctive vocalizations that their parents can easily recognize, but the non-colonial Rough-winged Swallow does not. Adoption Obviously, it would appear beneficial to avoid adopting other individual’s offspring, but such adoptions sometimes happen. In colonially nesting gulls chicks that have been poorly fed in their own nests sometimes leave their natal nest and join another brood, where they often are adopted. Adoption Moving is often a good decision for the chick because it may end up being better cared for in a different nest. However, adoptive parents on average lose 0.5 young of their own as a result of the adoption so why do they tolerate the intruder? Adoption Most likely explanation is that parents use an imperfect behavioral when deciding who to feed. Any chick that begs confidently is accepted and fed. Adoption The reason that gulls do not discriminate more is probably that recognition errors would be too costly. Errors in which a gull fails to feed or worse attacks and kills its own chick because it thinks it is a stranger would be very costly. The cost of occasional adoptions appears to be low enough that selection has not favored higher levels of discrimination in gulls. Adoption In some instances adoption appears not to come with a cost and may be beneficial to the adopter. It is common in ducks for females to accept extra eggs laid in their nests and to accept stray ducklings into their broods. Adoption In ducks there is little or no cost to adoption because chicks forage for themselves. The benefit appears to be that there is a predator dilution effect with larger broods. Additional young in the brood reduce the odds of a chick taken from the brood being the parents own young. Brood parasitism There are several species of birds that are obligate interspecific brood parasites. These include Old World Cuckoos, Old World Honeyguides and New World Cowbirds. These birds lay their eggs in the nests of other birds and provide no parental care. European Cuckoo removing host’s egg Brood parasitism Based on phylogenetic analyses brood parasitism appears to have evolved independently three times in the cuckoos and a large number of cuckoos (53 of 136 species) are brood parasites. Obligate brood parasites indicated in blue. Occasional parasites in red. Brood parasitism Interspecific brood parasitism is believed to have originated as intraspecific brood parasitism. Intraspecific brood parasitism is common in birds and has been recorded in more than 200 species. A plausible transition to interspecific brood parasitism would be for birds to begin laying eggs in the nests of closely related species. Brood parasitism Today cuckoos concentrate on species that are not closely related to them, but as parasitism in cuckoos may be 60 million years old this may simply reflect the long period of evolution that has occurred since the origin of the behavior. Brood parasitism In cowbirds, which much more recently evolved brood parasitism (in past 3-4 million years) the living species believed most like the ancestral parasite parasitizes only one other species and that belongs to its own genus. Since then increasingly general brood parasitism appears to have evolved. Brood parasitism Brood parasites have a significant effect on the reproductive success of the hosts. Baby cuckoos eject the eggs and young of the host so the host rears no young of its own. Brood parasitism Brood parasites exploit the host parents tendency to feed the largest young in a brood the most food and to reward the young that can reach highest for food. By laying in the nests of smaller birds, cuckoos give their young an advantage in the competition for food. So do cowbirds whose eggs hatch after a shorter incubation period which allows them to hatch before the host’s young. Brood parasitism The advantage of laying in the nests of smaller species has been shown in experiments in which nestlings of nonparasitic Great Tits and Blue Tits were switched between nests. The smaller Blue Tits did badly in Great Tit nests, but Great Tits prospered in Blue Tit nests. Why tolerate parasite’s eggs? Given the heavy costs of rearing a parasite, why don’t hosts reject parasitic eggs? Rejection also comes with costs so costbenefit analysis is needed. Why tolerate parasite’s eggs? Some birds do recognize parasitic eggs and remove them from the nest. However, there is a risk that the host will discard one or more of its own eggs in error. Reed Warblers have been shown to make this mistake. Why tolerate parasite’s eggs? Accepting a parasite’s egg is even more likely to be adaptive when the host is too small to remove the parasitic egg. Such hosts must either accept the egg or abandon the nest, which is an expensive option, especially if nest sites are scarce (e.g. as in cavity nesters). Why tolerate parasite’s eggs? Consistent with this hypothesis, Prothonotary Warblers parasitized by cowbirds are much more likely to abandon their nest if there are alternative nest sites on the male’s territory. 12.18 Why tolerate parasite’s eggs? Similarly, Yellow Warblers parasitized near the end of the breeding season tend to accept parasitic eggs, presumably because there is too little time to start over. Why tolerate parasite’s eggs? Another reason for hosts to tolerate parasite eggs is that the parasite may monitor the nest and harm the host’s nest if its egg is removed. This “Mafia hypothesis” has been supported by studies of Great Spotted Cuckoos and their Magpie hosts. Why tolerate parasite’s eggs? Magpie nests from which cuckoo eggs were ejected suffered a much higher rate of predation (87%) than nests that accepted cuckoo eggs (12%). Threatening the clutch of the hosts appears to be an effective strategy because renesting is costly in the magpies’ seasonal environment. Arms race between hosts and parasites. As selection operates on both hosts and parasites the differing selection pressures have resulted in an arms race between hosts and parasites. In the case of the European cuckoo and its hosts selection has led to extremely good mimicry of host eggs. Arms race between hosts and parasites. Individual cuckoos specialize on one host species and lay eggs that closely mimic only that species’ eggs. Historical interactions between cuckoos and some hosts appear to have resulted in victory for the host. Arms race between hosts and parasites. E.g., European blackbirds are rarely parasitized by cuckoos and even though under no current selection pressure, these birds reject parasitic eggs at a very high frequency. Apparently, blackbirds evolved rejection behavior in the past and cuckoos have moved on to other host species. Arms race between hosts and parasites. With many other species race arms-race between parasites and hosts is ongoing. Horsfield’s Bronze-cuckoo parasitizes the Superb Fairy Wren. Fairy-wrens respond to cuckoo eggs laid before they have started laying by abandoning nest or building over the egg. They also abandon if cuckoo lays egg after incubation has begun Arms race between hosts and parasites. Bronze-cuckoos have responded by inserting eggs during fairy-wren laying period. Such eggs are generally accepted and incubated. However, when young cuckoo pushes young wrens out of nest, fairy-wrens abandon the nest about 40% of the time and cuckoo starves. Arms race between hosts and parasites. In other cases cuckoo appears to fool parents into believing their sole chick is a fairy-wren. An important factor in the chick’s ability to fool the fairy-wren parents is its ability to mimic the begging call of young fairywrens. Chicks of Horsfield’s Bronze-cuckoo closely mimic calls of host fairy-wrens. Shining Bronze Cuckoo which rarely parasitizes fairy wrens does not resemble fairy-wren chick and does not sound like it either. Arms race between hosts and parasites. Another example of the use of calls in the arms race between parasites and hosts is that of calls by European Cuckoo chicks in Reed Warbler nests. The rate at which cuckoos call simulates that of a whole brood of Reed Warblers which encourages parents to feed at a much higher rate than they otherwise would. Blackbird chick placed in nest. Control is delivery rate when no tape played. Cuckoo is delivery rate when cuckoo begging call played. Reed warbler brood is delivery rate when tape of a brood of reed warblers in played. Parental favoritism and siblicide Parents may be related to all of their offspring equally, but often do not treat them equally well. In many cases parents actively discriminate against certain offspring and either allow them to starve or allow their siblings to kill them. Parental favoritism and siblicide For example, in African Black Eagles the first hatched of two chicks attacks its younger sibling as soon as it hatches and pecks it to death. Similarly in egrets, boobies, pelicans and other birds older siblings attack and drive younger offspring out of the nest where they starve to death. Young great egrets fight while their parent ignores the behavior. At a Brown Booby nest the older chick (under its parent) has driven its smaller sibling from The nest where it will die of exposure and starvation. Parental favoritism and siblicide Despite the fact some of their offspring are being killed, parents seem not only to tolerate the behavior, but to actively encourage it. Parental favoritism and siblicide For example, in Black Eagles incubation begins as soon as the first egg is laid. As a result the first egg hatches 3-7 days before the second and so the older offspring has a huge size advantage over its younger sibling and can easily kill him. Parental favoritism and siblicide Such hatching asynchrony is very common among birds and results in hatching asynchrony, which establishes an age and size hierarchy within the brood. Birds do not have to hatch their young asynchronously and many birds (e.g. ducks) even though they lay large clutches hatch their young synchronously. Parental favoritism and siblicide In cattle egrets (and other birds) in addition to promoting hatching asynchrony, parents spike the earlier laid eggs with high doses of androgens (male hormones). The hormones make the earliest hatched chicks more aggressive and gives them an extra advantage over later hatched chicks. Parental favoritism and siblicide Why do parents play favorites and facilitate siblicide? There are two major reasons: Insurance against failure Environmental uncertainty Insurance The most extreme form of brood reduction is obligate brood reduction in which younger offspring essentially always die. Examples of obligate brood reducers include: Black Eagles, Harpy Eagles, Giant Pandas, and Hooded Grebes. Insurance These animals have no intention of rearing more than a single offspring. The second offspring represents an easily cancelled insurance policy against the failure of the first offspring to hatch or develop normally. Insurance When the first offspring arrives it kills its sibling (Black Eagle), the parents cover over the second egg (Harpy Eagles), the parents abandon the second egg (Hooded Grebes) or abandon the second born cub (Giant Pandas). Thus, the parents avoid prolonged investment in a back-up offspring. However, if the first offspring fails the second can step in and take its place. Insurance Why don’t these animals go ahead and rear the second baby once it arrives? In many cases parents would appear to be capable of rearing two young, but don’t do so? Why not? Trade-offs Because there are trade-offs between offspring number and quality as well as between offspring number and parental future reproductive success. For these species it is usually not possible to provide enough food to rear two high-quality young. Pandas feed on low quality food and the burden of providing milk for two cubs is too much for most mothers. Two weakling offspring are worse than a single sturdy cub. Trade-offs In addition, extra effort invested in trying to rear two young in a season generally reduces future reproductive success by reducing lifespan and ability to produce eggs or babies. Environmental uncertainty Many other species are facultative brood reducers which means that brood reduction does not always occur. These species practice a policy of parental optimism. They lay a clutch size that can be reared in a good year, but in a bad year will result in brood reduction. Environmental uncertainty In these species the brood contains two classes of offspring: core and marginal offspring. Marginal offspring are handicapped by the parents and as in obligate brood reducers have insurance value, but mainly are produced so that parents can take advantage of a good year if one occurs to rear bonus offspring. Environmental uncertainty Consistent with this idea, in facultative brood reducers, the handicap the parents create is enough to create a clear hierarchy in the brood but not so great that it cannot be overcome. Environmental uncertainty Thus, in cattle egret broods the effects of A and B chicks (the eldest chicks) aggression towards younger C and D chicks is moderated by food supply. If food is plentiful, the younger chicks can tolerate the beating and may survive to fledge. If food is scarce the younger chicks quickly starve or are driven out of the nest and die. Environmental uncertainty The cattle egret parents’ policy of hatching asynchrony thus creates a situation in which in good years conditions can be taken advantage of and extra babies reared, but in bad years the brood can be efficiently reduced to what foraging conditions will support. Environmental uncertainty The amount of asynchrony in cattle egret broods appears to have been tailored by natural selection to maximize parents reproductive success and efficiency in rearing babies. Artificially synchronized nests produced fewer survivors and required more food because offspring fought more and so expended more energy. Environmental uncertainty Nests in which asynchrony was exaggerated produced similar numbers of young as normally asynchronous nests, but brood reduction took place at younger ages, which may limit the ability of the parents to rear large broods in good years. Brood reduction and humans Discussions of brood reduction are applicable to humans also. Twin births are rare, but twin conceptions are much commoner and only one in ten to one in fifty twin conceptions produce twins. The other pregnancies result only in singleton births. Brood reduction and humans This phenomenon has been dubbed the “vanishing twin” syndrome. Part of the phenomenon may be that producing extra eggs is an insurance strategy against pregnancy failure due to defective embryos. Some of these early embryos have chromosomal defects and are quietly aborted by the mother. Brood reduction and humans This idea is supported by the fact that older women are more likely to give birth to twins than younger women. Apparently this is because older women polyovulate more than younger women and older women are much more likely to produce chromosomally defective eggs. Brood reduction and humans It is possible that other cases of disappearing twins may not be caused by an embryo failing because it is defective, but from a “decision” by the mother to reduce her brood, although a mechanism by which this might occur has not been identified. Evaluating the reproductive value of offspring As we have seen not all offspring are created equal and even in the absence of parental manipulation of quality we would expect parents to assess offspring quality when deciding how to allocate scarce resources. Evaluating the reproductive value of offspring It has been suggested that the gape color of baby birds may signal the quality of their immune system and thus offspring quality Red gape color is produced by carotenoid pigments in the blood and these are believed to enhance immune function. Evaluating the reproductive value of offspring In an experiment on barn swallows in which chicks gapes were colored with food coloring chicks whose gapes were reddened received more food, although chicks whose gapes were yellowed did not receive less food. Evaluating the reproductive value of offspring Alternative explanations for the role of gape coloration have been put forward, however. An obvious alternative is that parents are not assessing offspring quality, but just feeding those chicks whose gapes are more conspicuous under the prevailing lighting conditions. Evaluating the reproductive value of offspring Consistent with this idea Great Tit chicks whose mouths were painted yellow received more food than chicks whose mouths were painted red and were less conspicuous in a dark nest box. When a plexiglass lid was placed on the nest box however, both sets of chicks were equally well fed. Evaluating the reproductive value of offspring Although gape color may not signal offspring quality or value other traits may. Coots have an unpleasant way of reducing brood size. They peck certain babies in their brood when they beg for food and these ones quickly die. Evaluating the reproductive value of offspring Baby coots have prominent long orange tipped plumes on their backs and throats and these may be a cue parents use in deciding which chicks they wish to feed. When these plumes were trimmed from half the members of a brood the unaltered members of the brood received more food and grew faster than the trimmed birds. Evaluating the reproductive value of offspring Control broods in which all birds were trimmed survived as well as broods in which no chicks were trimmed. Coots thus appeared to discriminate against trimmed chicks because they lacked orange plumes not because they could not recognize them. Thus, it may be that the orange plumes are a signal of offspring quality. Magpie assessment of offspring value Magpie young are increasingly likely to survive as they age. Thus their value increases and one would expect parents to value them more. Consistent with this parents are more likely to engage in defensive behavior when a predator approaches a nest if the brood is older.