Week 13-14 (5/6-5-9) -

advertisement

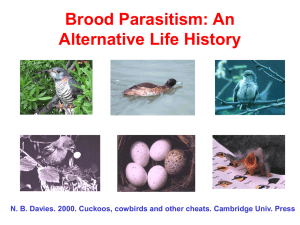

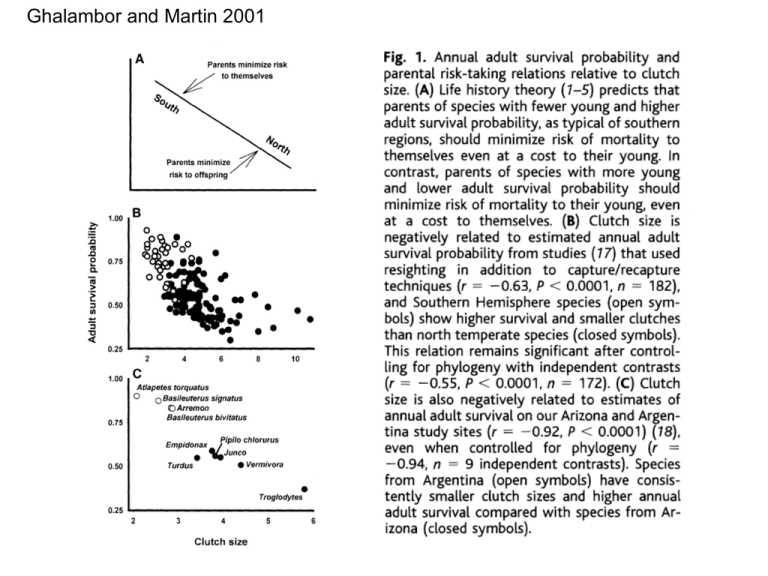

Ghalambor and Martin 2001 Ghalambor and Martin 2001 Figure 12.2 Parental care is provided by females in the Membracinae Figure 12.5 Parental care costs female St. Peter’s fish more than it costs males Figure 12.6 Male water bugs provide uniparental care Figure 12.7 Evolution of brood care by males in the Nepoidea Brown and Wilson 1992 Scott 1998 Figure 12.12 Male baboons intervene on behalf of their own offspring when young baboons start fighting with one another Yamazaki et al. 2000 Yamazaki et al. 2000 Wedekind et al 1995 Figure 12.10 Call distinctiveness facilitates offspring recognition by parents Figure 12.13 Why seek adoptive parents? Figure 12.14 Specialized brood parasitism by cuckoos has evolved three times Figure 12.15 Evolution of brood parasitism among cowbirds Figure 12.16 Widowbirds parasitize closely related species Figure 12.17 The size of an experimental “brood parasite” nestling relative to its host species determines its survival chances Figure 12.18 The transition to obligate parasitism was probably abrupt in most groups of birds Figure 12.19 The probability that a female prothonotary warbler will nest again in her territory is a function of the number of potential nest sites in her territory Figure 12.20 Egg removal by a cuckoo Figure 12.21 The mafia hypothesis as tested with parasitic cowbirds and prothonotary warblers Figure 12.22 A product of an evolutionary arms race? Figure 12.23 Adjustment of investment in sons and daughters by the red mason bee Osmia rufa Figure 12.24 Discriminating parental care by the burying beetle Nicrophorus vespilloides Trumbo and Fernandez 1995 Figure 12.25 Sibling aggression in the great egret Mock 1990 Ploger and Mock 1986 http://www.birdsasart.com/231/cattle%20egret%20feeding%20chick.jpg Schwabl et al. 1997 (cattle egrets) Mock and Ploger 1987 Figure 12.27 Parent boobies can control siblicide to some extent Figure 12.29 The color of the mouth gape affects the amount of food that nestling barn swallows are given by their parents