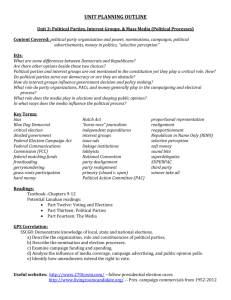

Campaign Laws and the Federal Election

advertisement

Campaign Finance Laws and the Federal Election Commission GOVT 2305 In this set of slides we touch on the history of US campaign finance laws, as well as the nature of the Federal Election Commission and the current state of campaign finance law in the United States. We will also look at Supreme Court decisions regarding constitutional issues surrounding campaign finance laws, as well as critiques of the effectiveness of these laws. Here are a few sites you might want to visit to get a preliminary look at the subject. From the Washington Post: A Special report on Campaign Finance. Wikipedias: Campaign Finance in the United States Campaign Finance Reform in the United States And Some Past Blog Posts on Campaign Finance, Citizens United, Money in Politics, and the Money Primary. It might be helpful to scroll through this: Open Secrets: Glossary of Terms. Notice that this subject will allow us to look at activities of each other three branches of government. Rules regarding campaign finance constantly evolve due to the interrelationship between each branch. A key question that will underlie the bulk of this section is whether campaign funding – especially the fact that funding is unequal – distorts democracy and. Does it cancel out the principle of majority rule and allow the wealthy to dominate the political process? Beyond that, is this a problem that requires a legal solution and if so, what type of solution? But this concern has to be balanced against the claim that campaign finance laws, by placing limits on campaign spending actually limit speech – which is a constitutionally protected right. First Amendment Center: Campaign Spending Campaign Spending, Free Speech, and Disclosure What follows is a walk through legislative, executive and judicial activities regarding campaign finance. It’s a good illustration of the checks and balances. A Walk through the History of Federal Campaign Finance Laws Campaign finance laws have four basic purposes: 1 - Limit contributions to ensure that wealthy individuals and special interest groups did not have a disproportionate influence on Federal elections 2 - Prohibit certain sources of funds for Federal campaign purposes 3 - Control campaign spending 4 - Require public disclosure of campaign finances to deter abuse and to educate the electorate. There were no federal laws related to campaign finance until the late 19th Century. Recall that politics in the early decades of the republic, as well as the colonial era, was explicitly elitist. Limiting suffrage to property owners restricted participation to the wealthy. Political bias towards wealthy property owners was a fact of life. As described elsewhere, campaigns during this period of time were informal and not all that expensive. Campaigning – as we know it - was considered undignified. There was no need to mobilize a large population. Campaigning involved connecting with a small handful of established elites. The need to have campaign laws did not arise until suffrage expanded and campaigns were necessary in order to win office. These needed to be funded. The need to campaign emerged with the rise of mass politics when suffrage was expanded to the nonproperty owners during the era of Andrew Jackson and the birth of the spoils system. “In the early nineteenth century, the spoils system was instituted, under which election winners rewarded their supporters with lucrative government jobs in return for their support. Government employees were then taxed an "assessment" to fund the political campaigns of the elected leaders and the political party in power. This led to the birth of modern political campaigns, in which politicians travel the state or country attempting to persuade citizens to vote for them. In order to succeed in these larger platforms, such campaigns required additional financial contributions from supporters. The first attempt to regulate campaign finance came in 1837, when Congressman John Bell of Tennessee, a member of the Whig Party, introduced a bill prohibiting assessments. Congress, however, did not vote on it.” – Source. These assessments became part of the glue that bound the various components of the political machines that began to dominate urban politics. Control over the flow of campaign cash allows for control over the political system. Contributions were expected from corporations and government employees, and anyone or anything with interests from the government. Recently, in Texas, this has been referred to as pay-to-play. The first federal campaign finance law, passed in 1867, was a Naval Appropriations Bill which prohibited officers and government employees from soliciting contributions from Navy yard workers. The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883. Established the United States Civil Service Commission and mandated that public jobs be awarded on the basis of merit, not political connections. It prohibited firing government employees for political reasons and soliciting campaign donations on federal property. Congress had been resistant to passing the law since they were politically dependent upon patronage. But the law’s passage was pushed following the assassination of James Garfield by an allegedly disgruntled office seeker. By making the agency a commission headed by a three person appointed panel it was hoped that the organization would be semi-independent and be able to make appointments without the control of the president. Note that the commission “was dissolved as part of the Civil Service Reform Act of 1978; the Office of Personnel Management and the Merit Systems Protection Board are the successor agencies.” The Tillman Act of 1907 prohibited monetary contributions to national political campaigns by corporations. It was promoted by Theodore Roosevelt after the 1904 when he was criticized for accepting corporate contributions. Note that TR had been William McKinley’s vice president who was elected president in 1896 and 1900. McKinley’s campaigns were run and funded with the assistance of the industrialist Mark Hanna. The 1896 campaign set records for campaign spending – mostly from businesses and corporations – that would last for 25 years. Click here for a timeline that argues that the election of 1896 was seen by the public as having been corrupt and it set the stage for campaign finance reform. Also note: “The 1896 campaign is often considered to be a realigning election that ended the old Third Party System and began the Fourth Party System.” This marked the rise of the business sector over the agrarian sector. The impact of the law was minimal. There was no enforcement mechanism and it did not apply to primary elections. Corporations found ways around the limits imposed by the law. The Publicity, or Federal Corrupt Practices Act, enacted in 1910 and amended in 1911 and 1925, placed limits on spending on campaigns and required that spending by political parties be disclosed to the public. Hatch Act of 1939 Prohibited members of the executive branch – with the exception of the president, vice president and a few other high ranking officials – from partisan political activity. The Hatch Act of 1939 and its 1940 amendments asserted the right of Congress to regulate primary elections and included provisions limiting contributions and expenditures in Congressional elections. – source. In 1936, labor unions began spending union dues to support federal candidates sympathetic to the workers' issues. This practice was prohibited by the SmithConnally Act of 1943, Pub. L. No. 78-89, 57 Stat. 163 (1943). Thus, labor unions, corporations, and interstate banks were effectively barred from contributing directly to candidates for federal office. Smith-Connally Act (1943) Prohibited unions from making direct contributions in federal elections. They soon found ways to make indirect contributions. In 1944, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), one of the largest labor interest groups in the nation, found a way to go around the constraints of the SmithConnally Act by forming the first political action committee, or PAC. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 further barred both labor unions and corporations from making direct expenditures and contributions in Federal elections. Labor unions moved to work around these limitations by establishing political action committees, to which members could contribute. PACs grew into major mechanisms for funneling corporate and union funds for campaigns. From Open Secrets: “PACs have been around since 1944, when the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) formed the first one to raise money for the reelection of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The PAC's money came from voluntary contributions from union members rather than union treasuries, so it did not violate the Smith Connally Act of 1943, which forbade unions from contributing to federal candidates. Although commonly called PACs, federal election law refers to these accounts as "separate segregated funds" because money contributed to a PAC is kept in a bank account separate from the general corporate or union treasury.” When the FEC was created, PACs were required to register with them and report their financial activities including where they received their money and how they spent it. Here’s a definition of a political action committee from the FEC’s website: “The term "political action committee" (PAC) refers to two distinct types of political committees registered with the FEC: separate segregated funds (SSFs) and non-connected committees. Basically, SSFs are political committees established and administered by corporations, labor unions, membership organizations or trade associations. These committees can only solicit contributions from individuals associated with connected or sponsoring organization. By contrast, non-connected committees--as their name suggests--are not sponsored by or connected to any of the aforementioned entities and are free to solicit contributions from the general public. For additional information, consult our Separate Segregated Funds and Nonconnected Committees fact sheet.” In addition to connected and nonconnected PACs, two types of PACs are worth pointing out: Super PACs Leadership PACs From Open Secrets: “A super PAC, also known as an independent expenditure-only committee, is a type of political action committee that came into existence in 2010 following a federal court decision in SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission. Super PACs may raise and spend unlimited sums of money for the sole purpose of making independent expenditures to support or oppose political candidates. Unlike traditional political action committees, super PACs may not donate money directly to candidates. Super PACs are required to disclose their donors to the Federal Election Commission, although some super PACs get around this requirement by listing 501(c) nonprofit groups as their donors -- these groups are not required to disclose their funders.” From Open Secrets: A leadership PAC is a “A fund-raising committee formed by a politician as a way to help fund other candidates’ campaigns or pay for certain expenses not related to the campaigns. Leadership PACs are often used by politicians who aspire to leadership positions in Congress. By making donations to other candidates, lawmakers hope to gain clout among their colleagues that the lawmaker will utilize in a bid for a leadership post or committee chairmanship. Politicians also use leadership PACs to lay the groundwork for their own campaigns for higher office. In recent years, leadership PACs have become commonplace, even among freshman members of Congress. Leadership PACs are considered separate from a politician’s campaign committee, providing donors with a way around limits on contributions to a candidate’s campaign committee. Individuals can contribute up to $5,000 per year to a member’s leadership PAC, even if they have already donated the maximum to that member’s campaign committee.” In recent elections, SuperPACs have spent more money on campaigns than have candidates. Here is a list of political action committees from Wikipedia For detailed information about PACs, click here for Political MoneyLine. Revenue Act of 1971 This law helped establish the system of presidential public funding used in the United States. The Revenue Act also placed limits on campaign spending by Presidential nominees who receive public money and a ban on all private contributions to them. Beginning with the 1973 tax year, individual taxpayers were able to designate $1 to be applied to the Presidential Election Campaign Fund. Controversy: Should elections receive public financing? What is public finance? Overview of state laws An Idea Worth Saving Ballotpedia Federal Election Campaign Act (1971) Required full reporting of campaign contributions and expenditures, limited spending on media advertising, and allowed for corporations and unions to “use treasury funds to establish, operate and solicit voluntary contributions for the organization's separate segregated fund (i.e., PAC). These voluntary donations could then be used to contribute to Federal races.” It also attempted to establish such a framework, but it was complex, decentralized and ineffective: ”. . . the Clerk of the House, the Secretary of the Senate and the Comptroller General of the United States General Accounting Office (GAO) monitored compliance with the FECA, and the Justice Department was responsible for prosecuting violations of the law referred by the overseeing officials. Following the 1972 elections, although Congressional officials referred about 7,000 cases to the Justice Department, and the Comptroller General referred about 100 cases to Justice,5 few were litigated. – source.” Reported campaign abuses in the 1972 presidential election – the Watergate era - led to a series of amendments in 1974. Support emerged for an independent body “to ensure compliance with the campaign finance laws.” This would be the Federal Election Commission. Question: Was the 1972 election especially corrupt? 1974 Amendments to FECA The amendments placed limits on both campaign contributions and expenditures. These applied to both candidates and PAC’s. As we will see below, some of these were declared unconstitutional. More importantly it established the Federal Election Commission: “ . . . an independent agency to assume the administrative functions previously divided between Congressional officers and GAO. The Commission was given jurisdiction in civil enforcement matters, authority to write regulations and responsibility for monitoring compliance with the FECA. Additionally, the amendments transferred from GAO to the Commission the function of serving as a national clearinghouse for information on the administration of elections.” This was the original process for placing people on the commission: “ . . . the President, the Speaker of the House and the President pro tempore of the Senate each appointed two of the six voting Commissioners. The Secretary of the Senate and the Clerk of the House were designated nonvoting, ex-officio Commissioners.” “The 1974 amendments also completed the system currently used for the public financing of Presidential elections. The amendments provided for partial Federal funding, in the form of matching funds, for Presidential primary candidates and also extended public funding to political parties to finance their Presidential nominating conventions.” The FECA was further amended in 1976 and 1979. The 1976 amendments repealed expenditure limits, changed how commissioners were appointed and limited PAC solicitations. The 1979 amendments “simplified reporting requirements, encouraged party activity at State and local levels and increased the public funding grants for Presidential nominating conventions.” The 1976 amendments retained a six member commission but changed how they were appointed: They were to be “appointed by the President of the United States and confirmed by the United States Senate. Each member serves a six-year term, and two seats are subject to appointment every two years. . . . The Chairmanship of the Commission rotates among the members each year, with no member serving as Chairman more than once during his or her term.” But the commission was to be evenly divided politically: “By law, no more than three Commissioners can be members of the same political party, and at least four votes are required for any official Commission action. Critics of the Commission argue that this structure regularly causes deadlocks on 3 -3 votes.” The purpose of the 1979 amendments was to draw a distinction between contributions to a specific candidates’ campaign and contributions intended to build parties and get out the vote. This was also a response to the decision in Buckley v Valeo – see below for more on that. This distinction became know as hard money and soft money. The former is regulated, the latter is not. But the problem was distinguishing between the two. The use of soft money negated the impact of the limits placed on hard money. From Open Secrets: “Hard Money” refers to the “regulated contributions from an individual or PAC to a federal candidate, party committee or other PAC, where the money is used for a federal election. Hard money is subject to contribution limits and prohibitions and can be used to directly support or oppose a candidate running for federal office. Hard money can pay for television ads, mass mailings, bumper stickers, yard signs and other communications that mention a specific candidate.” From Open Secrets: “Soft Money” refers to “Contributions made outside the federal contribution limits to a state or local party, a state or local candidate or an outside interest group. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 banned the national political parties from raising soft money. Unlike hard money, soft money was not supposed advocate the election or defeat of a federal candidate. At one time, unlimited soft money contributions were routinely solicited and accepted by the national political parties. The money was supposed to be used for state and local elections and generic “partybuilding” activities, including voter registration campaigns and get-out-thevote drives. However, the parties increasingly used soft money for so-called “issue” ads that criticized or touted a federal candidate’s record just before an election, as well as other activities that were intended to influence the outcome of a federal election. Soft money was considered by many to be a major loophole in campaign finance law that allowed the parties to raise hundreds of millions of unregulated dollars. The Democrats and Republicans together collected more than $500 million in soft money during the 2002 election cycle.” The amendments also provided opportunities for funding for generic advertising and the creation of “issue ads” intended to educate voters, not advocate for a specific candidate. But the line between advertisement for a specific candidate and a general issue ad was easily blurred. Which led to calls for further reform. Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), 2002 This law was passed to address the increased use of soft money and the proliferation of issue ads. It also increased contribution limits, addressed coordinated and independent expenditures, and increased disclaimers on advertising. It also included The millionaires amendment. The use of soft money was banned by national parties: It prohibited national political party committees “from raising or spending any funds not subject to federal limits, even for state and local races or issue discussion.” It limited issues ads “defining as "electioneering communications" broadcast ads that name a federal candidate within 30 days of a primary or caucus or 60 days of a general election, and prohibiting any such ad paid for by a corporation (including non-profit issue organizations such as Right to Life or the Environmental Defense Fund) or paid for by an unincorporated entity using any corporate or union general treasury funds.” It included the Stand By your Ad provision. Advertisement explicitly endorsing a candidate and stating the candidate’s opinions has to be endorsed by the candidate. I am X and I approve this message. See the FEC’s description of the act here. These would be challenged to the courts – more on this below. One consequence of the law: The rise of 527 Organizations. A definition from open secrets: A tax-exempt group organized under section 527 of the Internal Revenue Code to raise money for political activities including voter mobilization efforts, issue advocacy and the like. Currently, the FEC only requires a 527 group to file regular disclosure reports if it is a political party or political action committee (PAC) that engages in either activities expressly advocating the election or defeat of a federal candidate, or in electioneering communications. Otherwise, it must file either with the government of the state in which it is located or the Internal Revenue Service. Prior to the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court in January 2010, many 527s run by special interest groups raise unlimited "soft money," which they used for voter mobilization and certain types of issue advocacy, but not for efforts that expressly advocated the election or defeat of a federal candidate or amount to electioneering communications. The Citizens United ruling allows 527 committees to raise unlimited funds from individuals, corporations and unions to expressly advocate for or against federal candidates, and since the controversial ruling, several so-called 527 groups have registered with the FEC as "super PACs." An unsuccessful recent proposal: Democracy Is Strengthened by Casting Light On Spending in Elections Act. The Disclose Act This was a response to the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decisions. “The bill, as introduced, included banning U.S. corporations with 20 percent or more foreign ownership from influencing election outcomes through the use of campaign contributions; preventing Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) recipients from making political contributions; giving shareholders, organization members, and the general public access to information regarding corporate and interest group campaign expenditures; and requiring disclosure of membership information by organizations with more than 500,000 members that made political ads” It was successfully filibustered in the Senate in 2010, but has been revived periodically. Basic Provisions of Current Campaign Finance Law. It might be wise to walk through the specific provisions in current campaign finance law. In these following slides, we’ll walk through the content of this FEC webpage. In brief, the page states what donations do and do not need to be disclosed, describes contribution limits, details what contributions and expenditures are prohibited, defines independent expenditures, explains limits on corporate, union or party activities, describes the Presidential Campaign Fund Act and the grants available for primary and general elections as well as party conventions. Note that constitutional questions are commonly raised about all of these issues. Here we go: Disclosures: “The FECA requires candidate committees, party committees and PACs to file periodic reports disclosing the money they raise and spend. Candidates must identify, for example, all PACs and party committees that give them contributions, and they must identify individuals who give them more than $200 in an election cycle. Additionally, they must disclose expenditures exceeding $200 per election cycle to any individual or vendor.” Contribution Limits: The following table outlines campaign contribution limits for 2013-2014. Prohibited Contributions and Expenditures: “The following are prohibited from making contributions or expenditures to influence federal elections: Corporations, Labor organizations, Federal government contractors, and Foreign nationals. This refers to direct contributions, not independent expenditures. That is a controversial topic we’ll highlight below. Furthermore, with respect to federal elections: No one may make a contribution in another person's name or make a contribution in cash of more than $100. In addition to the above prohibitions on contributions and expenditures in federal election campaigns, the FECA also prohibits foreign nationals, national banks and other federally chartered corporations from making contributions or expenditures in connection with state and local elections. Independent Expenditures: “Under federal election law, an individual or group (such as a PAC) may make unlimited "independent expenditures" in connection with federal elections. An independent expenditure is an expenditure for a communication which expressly advocates the election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate and which is made independently from the candidate's campaign. To be considered independent, the communication may not be made with the cooperation, consultation or concert with, or at the request or suggestion of, any candidate or his/her authorized committees or a political party, or any of their agents. While there is no limit on how much anyone may spend on an independent expenditure, the law does require persons making independent expenditures to report them and to disclose the sources of the funds they used.” Here’s more detail on how the FEC deals with coordinated communications and independent expenditures. Corporate and Union Activity: Although corporations and labor organizations may not make contributions or expenditures in connection with federal elections, they may establish PACs. Corporate and labor PACs raise voluntary contributions from a restricted class of individuals and use those funds to support federal candidates and political committees. Political Party Activity: Political parties are active in federal elections at the local, state and national levels. Most party committees organized at the state and national levels as well as some committees organized at the local level are required to register with the FEC and file reports disclosing their federal campaign activities. Party committees may contribute funds directly to federal candidates, subject to the contribution limits. National and state party committees may make additional "coordinated expenditures," subject to limits, to help their nominees in general elections. Party committees may also make unlimited "independent expenditures" to support or oppose federal candidates, as described in the section above. National party committees, however, may not solicit, receive, direct, transfer, or spend nonfederal funds. Finally, while state and local party committees may spend unlimited amounts on certain grassroots activities specified in the law without affecting their other contribution and expenditure limits (for example, voter drives by volunteers in support of the party's Presidential nominees and the production of campaign materials for volunteer distribution), they must use only federal funds or "Levin funds" when they finance certain "Federal election activity." Party committees must register and file disclosure reports with the FEC once their federal election activities exceed certain dollar thresholds specified in the law. The Presidential Election Campaign Fund Act: Under the Internal Revenue Code, qualified Presidential candidates receive money from the Presidential Election Campaign Fund, which is an account on the books of the U.S. Treasury. Primary Matching Payments: Eligible candidates in the Presidential primaries may receive public funds to match the private contributions they raise. While a candidate may raise money from many different sources, only contributions from individuals are matchable; contributions from PACs and party committees are not. Furthermore, while an individual may give up to $2,600 to a primary candidate, only the first $250 of that contribution is matchable. To participate in the matching fund program, a candidate must demonstrate broad-based support by raising more than $5,000 in matchable contributions in each of 20 different states. Candidates must agree to use public funds only for campaign expenses, and they must comply with spending limits. Beginning with a $10 million base figure, the overall primary spending limit is adjusted each Presidential election year to reflect inflation. In 2012, the limit was $45.6 million. General Election Grants: The Republican and Democratic candidates who win their parties' nominations for President are each eligible to receive a grant to cover all the expenses of their general election campaigns. The basic $20 million grant is adjusted for inflation each Presidential election year. In 2012, the grant was $91.2 million. Nominees who accept the funds must agree not to raise private contributions (from individuals, PACs or party committees) and to limit their campaign expenditures to the amount of public funds they receive. They may use the funds only for campaign expenses. A third party Presidential candidate may qualify for some public funds after the general election if he or she receives at least five percent of the popular vote. Party Convention Grants: Each major political party may receive public funds to pay for its national Presidential nominating convention. The statute sets the base amount of the grant at $4 million for each party, and that amount is adjusted for inflation each Presidential election year. In 2012, the major parties each received $18.25 million. Other parties may also be eligible for partial public financing of their nominating conventions, provided that their nominees received at least five percent of the vote in the previous Presidential election. Supreme Court Cases Almost all campaign finance laws have been challenged in court. This should not be a surprise given the stakes associated with elections, as well as the degree to which financing campaigns overlaps constitutionally defined freedoms. Some of these challenges have been successful. An ongoing question: Do campaign finance laws, as designed and implemented, violate constitutional freedoms, especially the freedom of speech? Frontline: The Constitution and Campaign Finance. Many of the laws outlined above were challenged before the courts. Here is a look at some of these cases and what the courts decided. 1921 - Newberry v. United States Struck down the part of the Federal Corrupt Practices Act that placed spending limits on primary campaigns or other nominations processes for federal office: “Justice James Clark McReynolds held that the U.S. Constitution did not grant Congress the power to regulate primary elections or political party nomination processes.” 1934 – Burroughs v United States The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the reporting requirements of the Federal Corrupt Practices Act against a constitutional challenge. Congress has the power to pass laws that protect the integrity of the federal election process. The Hatch Act was challenged as being a violation of free speech, but the Supreme Court disagreed. “In passing the Hatch Act, Congress affirmed that partisan activity government employees must be limited for public institutions to function fairly and effectively. The courts have held that the Hatch Act is not an unconstitutional infringement on employees’ first amendment right to freedom of speech because it specifically provides that employees retain the right to speak out on political subjects and candidates.” 1976 Buckley v. Valeo This was an important challenged to the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971’s limits on campaign contributions and the ability of candidates to give unlimited money to their own campaigns. It ruled that limitations on contributions were constitutional, but limits on spending were not. “the case remains the starting point for judicial analysis of the constitutionality of campaign finance restrictions” Worth a look if you feel ambitious: The 527 Problem . . . and the Buckley Problem “ . . . the case held that restrictions on campaign contributions and spending, a form of political speech and association, could not be justified by the desire to equalize candidates, writing, “the concept that government may restrict the speech of some [in] order to enhance the relative voice of others is wholly foreign to the First Amendment.” However, the Court did find that the government's compelling interest in preventing "corruption or its appearance" could justify restrictions that went beyond bribery. The Court ruled that because contributions involved the danger of "quid pro quo" exchanges, in which the candidate would agree, if elected, to take or not to take certain actions in exchange for the contribution, limitations on contributions could generally be justified. However, the Court struck down limitations on spending by candidates and spending by others undertaken independently of candidates, on the grounds that spending money did not, by definition, involve such candidate/donor exchanges.“ - source Try to remember this point: Campaign contributions can corrupt; Campaign spending can not. At least according to the Supreme Court. This is still a controversial point: Campaign spending was defined as speech. Not everyone agrees. The decision also established that limits on campaign spending can only extend to express advocacy of a specific candidate. It cannot extend to groups involved in discussing candidates and ads without engaging in advocacy. This led to the rise of 527 organizations which are taxexempt under Section 527 of the Internal Revenue Code. “A 527 group is created primarily to influence the selection, nomination, election, appointment or defeat of candidates to federal, state or local public office.” Note that the distinction between PACs and 527 organizations is slippery. PACs are 527 organizations, but so can any other organization that provides information about political matters short of advocating for or against a candidate. By highlighting this distinction, Buckley v Valeo fueled the rise of these groups. 2003: McConnell v. FEC Key provisions of the BCRA were upheld, including the electioneering communications provision (disclosures were necessary for corporate and union funding of election ads and these ads could not run 30 days prior to primary elections and 60 days prior to general elections) and the soft money ban. The majority ruled that the limitations placed on speech (campaign finance) were minimal and were “justified by the government's legitimate interest in preventing "both the actual corruption threatened by large financial contributions and... the appearance of corruption" that might result from those contributions.” 2006: Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc. The ban on issue ads prior to elections established by the BCRA was limited, some members of the court expressed an interest in overturning the ban altogether. 2008: Davis v. Federal Election Commission The BCRA’s millionaire’s amendment was overturned. Detail from Scotus Blog here. 2008: Shays and Meehan v. FEC 2010: Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission Overturned restrictions on independent corporate and labor union expenditures in campaigns, notably the restriction on issue ads 30 days prior to primary elections and 60 days prior to general elections. The decision allowed corporations and unions to make direct independent expenditures on advertisements with political content and not funnel these through their political action committee. From Open Secrets: “Independent expenditures are advertisements that expressly advocate the election or defeat of specific candidates and are aimed at the electorate as a whole. Under federal rules, these expenditures must be made completely independent of the candidates, with no coordination. In January 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that corporations and unions may fund independent expenditures with money from their general treasuries. Prior to that, independent expenditures could only be made by the organization's PAC. In the wake of Citizens United, some groups continue to use their PACs to fund independent expenditures, while others are taking advantage of the new freedom to spend directly from treasury funds or through new "super PACs" that can use unlimited donations to run independent expenditures. Individuals, political parties, unions, corporations, PACs and other groups making independent expenditures must disclose the name of the candidates who benefit and must itemize the amounts spent in a report to the Federal Election Commission.” The decision was immediately controversial, some arguing that the court had rolled back restrictions on corporate and union involvement in elections dating back a century, other arguing that by granting free speech rights to corporations they fueled the perception that corporations are “people” under the law. Proponents argue the decision strengthened free speech. Opponents argued it opened the door for corruption, and electoral dominance by well funded business interests. The rise of 501(c)(4) organizations has been traced to this decision. Applying for 501(c)(4) status allows a group to be not only tax exempt, but to not have to disclose its donors. But they have to then prove that they are a social welfare organization not a political organization. But determining which is which is not only tough to do, but is politically problematic. See IRS Scandal for an example. For further reading on the case: Money Unlimited Open Secrets ScotusBlog 2010: Speechnow.org v. FEC This was not a Supreme Court case, but instead a DC Circuit Court case that applied the Citizens United decision to the fact that limits existed on the amount that individuals can make to 527 organizations. From Open Secrets: SpeechNow.org v. FEC was “A federal court decision in March 2010 that found that it was unconstitutional to impose a contribution limit on groups whose sole purpose was funding independent expenditures. The decision relied on the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission from January 2010, which granted corporations and unions the ability to use their general treasury money for political expenditures. In the wake of the SpeechNow.org decision, scores of new groups -often called super PACs -- declared to the Federal Election Commission their intent to raise unlimited donations from corporations, unions and individuals.” This further expounded the idea that free speech rights applied to any entity making an independent expenditure in an election. The court noted that the language of the First Amendment stated that laws could not restrict speech without mentioned the source of that speech. Registering as a PAC and reporting contributions did not violate constitutional freedoms and were both upheld. Click here for the FEC’s description of the case. A final concluding point for this section: We’ve seen a revolution in attitudes about campaign funding initiated by the court. It’s very likely still underway. Cases are commonly accepted that make claims that current restrictions on campaign funding are unconstitutional. Here is a contemporary example as I’m writing this: are aggregate limits on contributions from individuals unconstitutional? Note: The Supreme Court also has a handful of rulings dealing with state and local campaign laws. I cover these in GOVT 2306, as well as those cases unique to Texas. The Federal Election Commission The FEC is the national executive agency charged with overseeing campaign finance. Prior to its creation, campaign finance laws had no teeth. So until 1975, there was no mechanism in place to address issues associated with campaign finance, and even since then, there have been questions about the effectiveness of the commission. A description of the agency from the FEC webpage : In 1975, Congress created the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to administer and enforce the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) - the statute that governs the financing of federal elections. The duties of the FEC, which is an independent regulatory agency, are to disclose campaign finance information, to enforce the provisions of the law such as the limits and prohibitions on contributions, and to oversee the public funding of Presidential elections. The Commission is made up of six members, who are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. Each member serves a six-year term, and two seats are subject to appointment every two years. By law, no more than three Commissioners can be members of the same political party, and at least four votes are required for any official Commission action. This structure was created to encourage nonpartisan decisions. The Chairmanship of the Commission rotates among the members each year, with no member serving as Chairman more than once during his or her term. If you’d like, here’s a link to the Federal Election Commission’s You Tube Page. It contains a variety of videos describing different aspects of the commission. And here’s the Wikipedia. As with all independent regulatory agencies, it not only oversees the implementation of law over a specific subject, it has the ability to issue rules and advisory opinions over what it sees as proper within its mandate. But since the industry it regulates is the electoral industry, there are questions about whether it has been captured by it. Since the electoral industry includes members of Congress as well as the president, there are further questions about whether these people want the FEC to have the power to regulate elections according to the law. Advisory Opinions The FEC and the Campaign Finance Law Federal Election Commission Meeting Notices and Rule Changes http://www.fec.gov/law/law_rule makings.shtml Is the FEC effective? Is it a broken agency? Is it a captured agency? From FixTheFEC.org: Senator John McCain (R-AZ) regularly refers derogatorily to the FEC as the “the little agency that can’t” or the “muzzled watchdog,” for good reason. By design it was structured to be ineffective and glacially slow. Put simply, the Commission is excessively partisan and political, the enforcement process is cumbersome and inefficient, and the penalties levied are too anemic to deter violations of the law. To be sure, Congress has a vested interest in preventing any reform of the FEC; members, after all, would be the targets of many enforcement actions. Some concluding thoughts