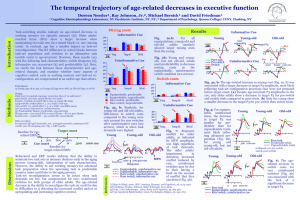

0 - New York State Psychiatric Institute

advertisement

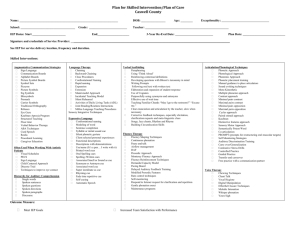

Frequent change can be good for you: ERP evidence that task switch probability affects cognitive control Michael Bersick (1), Doreen Nessler (1), Ray Johnson, Jr. (2), and David Friedman (1) Mixing Costs Baseline for cuerelated ERPs 1a 300 250 250 200 200 150 150 100 100 50 50 0 0 Pz cue onset 500 4 ? 4 1000 ms more/less than 5? odd/even? 1b [1] Monsell & Mizon (2006). JEP: HPP (32), 493-516. [2] Wylie & Allport (2000). Psychological Research (63), 212-233. [3] Schneider & Logan (2006). JEP: General (135), 623-640. MFN Pz 5a Cue-related P3 500 1000 ms -1000 -500 0 Cz 7a 500 1000 ms Fz 8 7b 0 500 1000 ms RT 200 400 ms Informative cue, unpredictable Informative cue, predictable Uninformative cue, unpredictable Uninformative cue, predictable Cz 6b target onset Fig. 4: (b) Informative cues preceding equiprobable, unpredictable switches elicited a parietal, P3-like effect relative to pre-switch trials. (a) This effect was absent for informative cues on equiprobable, predictable switch trials. Fig. 5: (a) and (b) Informative cues preceding both predictable and unpredictable rare switches elicited much larger amplitude P3s than those present in the equiprobable condition (cf. Fig 4). Cz 6a Cz Pz 5b 4b Fig. 6: After uninformative cues, the decrease in the amplitude of the target P3 was larger for unpredictable (b) than for predictable (a) pre-switch and switch trials. Fig. 7: (a) and (b): Target P3s to rare switch and preswitch stimuli. Fig. 8: After uninformative cues, response conflict, as indicated by the amplitude of the MFN, was larger for unpredictable than predictable, equiprobable switches. Target P3 Rare switch (b) Unpredictable Rare Switch Uninformative cue Equiprobable 4a Pz Predictable, informative cue Unpredictable, informative cue Predictable, uninformative cue Unpredictable, uninformative cue Fig. 3: Informative cues reduced switch costs. In addition, when switches were equiprobable switch costs after uninformative cues were significantly reduced. Single task Pre-switch Switch (a) Predictable Switch Costs Equiprobable Rare Switch Fig 2: Informative cues reduced mixing costs. Mixing costs decreased dramatically after uninformative cues in the equiprobable condition, but only when task order was predictable. Informative cue -1000 -500 0 Informative References 300 Equiprobable Target onset 300 800 1300 0 Cue onset Baseline for target-related ERPs Uninformative 350 0 500 1000 ms target onset Discussion EEG recording: 62 sintered Ag/AgCl electrodes; referred to averaged mastoids; continuous DC100Hz; 500 Hz sampling rate; Fig. 1a: ERP epochs. 350 Rare switch Participants: Fifteen young adults (19 to 30 years; M = 24.6; SD = 3.8). Design: Digit (not 5) required response: more/less than 5? or odd/even? pure blocks: one task; mixed blocks: two tasks. Factors: (1) Ratio of switch (S) to stay or repeat (R) trials equiprobable; switch after 0, 1, or 2 trials: a-bb-aaa rare switch 1:3; switch after 2, 3, or 4 trials: aaa-bbbb-aaaaa (2) Cue-status: informative, uninformative (Fig. 1b); (3) Predictability Status: predictable, unpredictable Mixing costs = pre-switch RTs in mixed blocks - RTs in pure blocks Switch costs = switch RTs – pre-switch RTs mixed blocks Results The cost of switching between two tasks is reduced by providing a cue warning of an impending switch. Cognitive control accounts of this effect claim that an informative cue allows for task-set reconfiguration prior to the actual switch [1]. Nevertheless, the fact that switch costs remain even after a long preparatory interval suggests that different task sets can interfere with each other [2]. However, such proactive interference might only be a problem when successive task sets must be reactivated. If switching is frequent, then keeping both task-sets active is a good strategy, assuming that little cost accrues from doing so. We examined how switch probability, switch predictability, and informative-cue availability interact to change the ease with which participants can maintain and access different task sets. Equiprobable Methods Introduction 1 Cognitive Electrophysiology Laboratory, NY State Psychiatric Institute, NY, NY;2 Department of Psychology , Queens College/CUNY, Flushing, NY Participants seem to utilize predictive information to actively maintain both task sets when doing so aids performance. Decreased mixing and switch costs for predictable, equiprobable stimuli, the decrease of cue-related P3 amplitude from rare to equiprobable switches, and the absence of any P3 to informative cues for equiprobable, predictable switches all suggest that cue information is increasingly irrelevant to performing the task as switches become more probable and predictable. Although response conflict was highest after uninformative cues, smaller target P3s for predictable vs. unpredictable equiprobable switches were observed, suggesting that predictability allowed processing resources to be conserved. Participants may also have created a more global behavioral set encompassing both tasks [3]. Switch costs in the equiprobable condition might be best described as relatively “pure” costs of switching between active task sets rather than as proactive interference.