Critical Legal Studies

advertisement

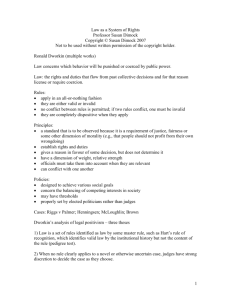

Dworkin and Critical Legal Studies . Law’s Empire pp. 271-75 Perhaps even…partial success is unavailable; perhaps every interpretation he considers is inconsistent with the bulk of the material supplied to him. In that case he must abandon the enterprise, for the consequence of taking the interpretive attitude toward the text in question is then a piece of internal skepticism: that nothing can count as continuing the novel rather than beginning anew.” 230-1 The chain novel analogy It’s easy to see how in some cases the chain novel might prove impossible to continue with integrity. Just imagine that earlier writers introduced too much weirdness for a coherent story to be possible. Could something similar happen in law? What factors constrain sharp breaks in the chain of law? Do serious legal contradictions get addressed in practical ways? They are likely to lead to litigation or legislation that will diminish the conflict. Dworkin says as much: “Contradiction between two areas of law so closely related [as two parts of contract law] would almost certainly also be eroded by the practices of precedent and academic criticism and restatement.” Reply to Waldron in Hershowitz, ed. Exploring Law’s Empire, 302 Stability in law and legal interpretation Stability is promoted by: • Shared paradigms. “Any…judge who denied that the traffic code was part of the law would be replaced, and this fact discourages radical interpretations.” 88 • Precedent—“which no judge’s interpretation can wholly ignore.” 88 • The social nature of legal practice. “Judges think about law…within society, not apart from it; the general intellectual environment, as well as the common language…exercises practical constraints on idiosyncrasy.” 88 • Shared views about which texts are relevant. 91 • Shared views about the legal furniture which is in place. What about stability in legislation? The critical legal studies movement “Although the intellectual origins of the Critical Legal Studies (CLS) can be generally traced all the way back to American Legal Realism, as a distinct scholarly movement the CLS fully emerged only by the late 1970s. Many first-wave CLS scholars [were] profoundly influenced by the twin experiences of the radical civil rights movement and the anti-war movements of the late 1960s. What started off as a critical stance towards American domestic politics eventually translated into a critical stance towards the dominant legal ideology of the modern Western society…. [T]he "crits" sought to demystify the numerous myths at the heart of the mainstream legal practice.” Wikipedia: Critical Legal Studies Dworkin on “What is “Critical Legal Studies”? “Critical legal studies resembles the older movement of American legal realism….” “At its best and most promising, however, it escapes the limits of legal realism by reaching for the global and threatening form of internal skepticism…. It argues that our legal culture, far from having any shape amenable to a uniform and coherent justification of principle, can only be grasped through the infertile metric of contradiction.” LE 272 Dworkin on how the Crits would interpret McLoughlin In McLoughlin CLS would tell a story of conflicting principles respecting individual loss in accidents: “of two deeply antagonistic ideologies at war within the law, one drawn, perhaps, from communitarian impulses of altrusim and mutual concern and the other from the contradictory ideas of egoism, selfsufficiency, and judgmental moralism.” LE 272 CLS would say that “Hercules must fail in imposing a coherent structure on law’s empire as a whole.” LE 273 [Would CLS agree to use the Hercules idea?] Dworkin’s view of the central claim of CLS According to the crits, “Hercules must fail in imposing a coherent structure on law’s empire as a whole.” The reason is that our law contains “deeply antagonistic ideologies at war….” 272 CLS “argues that liberalism, as a philosophical system combining metaphysical and ethical ideas, is profoundly self-contradictory and that the contradictions of liberalism therefore ensure the chaos and contradiction of any available interpretation of our law.” 274 Duncan Kennedy on contradiction “Kennedy writes that the opposing ethical conceptions which inform legal doctrine ‘reflect a deeper level of contradiction. At this deeper level, we are divided, among ourselves and also within ourselves, between irreconcilable visions of humanity and society, and between radically different aspirations for our common future.” Andrew Altman, “Legal Realism, Critical Legal Studies, and Dworkin” (1986) 217 Roberto Unger on internal conflict “…it would be strange if the results of a coherent, richly developed normative theory were to coincide with a major portion of any extended branch of law. The many conflicts of interest and vision that lawmaking involves, fought out by countless minds and wills working at cross purposes, would have to be the vehicle of an immanent moral rationality whose message could be articulated by a single cohesive theory. This daring and implausible sanctification of the actual is in fact undertaken by the dominant legal theories.” AA 222 Legal realism and indeterminacy Judges have “tremendous leeway in being able to redefine the holding and the dictum in the precedential cases. This leeway enabled judges, in effect, to rewrite the rules of law on which earlier cases had been decided. The upshot was that in almost any case which reached the stage of litigation, a judge could find opinions which read relevant precedents as stating one legal rule and other opinions which read the precedents as stating a contrary rule.” AA 209 Altman on Hercules “If the rule of law is to be a guiding ideal for humans, and not just gods, then the problem of legal indeterminacy must be resolvable from a human point of view.” AA 220 Jeremy Waldron “Did Dworkin Ever Answer the Crits?” “My aim in this paper is to explore the extent to which Professor Dworkin is put to a hard choice between the agile and discerning constructivism he needs to respond to CLS, on the one had, and the integrity thesis…which he invokes to justify the claim that making coherent sense of the existing legal materials, foreground and background, is something we are morally required to do. I think Dworkin really is confronted with a dilemma here….” Waldron 156 Are Dworkin and the crits trying to answer the same question? CLS and Dworkin have “a common interest in what I would like to call the ‘background elements’ of a legal system—the principles and policies that lie in back of the rules and texts that positivists emphasize.” Waldron 155 Maybe not. Perhaps the crits are interested in broad underlying ideologies and Dworkin in specific principles of “fairness, justice, and procedural due process.” Waldron on possible responses: competition versus contradiction “Dworkin’s second response is to argue that this sort of CLS skepticism neglects an important philosophical distinctions between competing principles (such as autonomy and mutual concern)…, and contradictory principles (such as equality and inequality) which cannot possibly be combined in one coherent conception.” W 167 Crits may, of course, be skeptical that humans can deal adequately with the balancing of competing principles that Dworkin’s view requires. See W 168 The contradiction/competition distinction Hercules “constructs two principles: that people should not be held responsible for causing injury they could not reasonably foresee and that people should not be put at disadvantage, in the level of protection the law gives them, in virtue of physical disabilities beyond their control. He has no difficulty recognizing both at work in the law of tort and more generally, and no difficulty in accepting both at the level of abstract principle. These principles are sometimes competitive, but they are not contradictory. He asks whether past decisions in cases in which they do conflict have resolved them coherently. Perhaps they have, though whatever account he accepts of that resolution will probably require him to treat some past decisions…as mistakes.” 443-4 Waldron on possible responses: You don’t know if it’s worth trying until you try For the search for unifying principles to be worth trying “it must not be out of the question that our argument or our principles fit a significant portion of the legal materials.” “This is where Dworkin should take his stand against the Crits. He should say (and he does say): it is not clear up front that attempts to argue in the mode of law-as-integrity are doomed to failure. If it were clear, we should have no reason to resist the siren charms of pragmatism: forget the existing law; ask instead what’s best for the future; and take one’s chances on the integrity issue. But sometimes legal argument looks promising, and when it does were are obliged to make the attempt (and the theory of integrity explains why).” W 181 Dworkin’s criticisms of CLS The “skeptical interpretative claim” that CLS makes “is powerful and germane, however, only if it begins where Hercules begins: it must claim to have looked for a less skeptical interpretation and failed….The internal skeptic must show that the flawed and contradictory account is the only one available.” 273-4 “Arguments…about the incoherence of liberalism…have been spectacular and even embarrassing failures. They begin and end in a defective account of what liberalism is, an account supported by no plausible reading of the philosophers they count as liberals.” 274 Further, CLS writers ignore “the distinction we have just found crucial to any internally skeptical argument, the distinction between competition and contradiction in principles. The contemporary focus helps “A contemporary Congress might disown the principles that inspired Social Security in the New Deal.” “No contradiction between what the law permits or requires in different historical stages of a community’s culture can pose any difficulty for a contemporary judge seeking integrity within contemporary law. So Waldron must suppose that the Crits have established more than a historical claim: that they have shown contradiction in the American community’s contemporary legal practice. But Waldron offers no examples at all of the conflicts he supposes endemic in that practice.” --Reply to Waldron in Hershowitz, ed. Exploring Law’s Empire, 303, 299. Dworkin’s final reply to the crits “Their work is useful to Hercules, and he would neglect it at his peril, because it reminds him that nothing in the way his law was produced guarantees his success in finding a coherent interpretation of it it.” “But neither does history guarantee his failure, because his ambitions are interpretive in the sense appropriate to the philosophical foundations of law as integrity. He tries to impose order over doctrine, not to discover order in the forces that created it. He struggles toward a set of principles he can offer to integrity, a scheme for transforming the varied links in the chain of law into a vision of government now speaking with one voice, even if this is very different from the voices of leaders past.” 273 “An imaginative interpretation can be constructed on morally complicated, even ambiguous terrain.” 228 Perhaps Hercules can pull off such a constructive reinterpretation, but can ordinary judges? Is legitimacy undermined if judges can only pursue integrity in a limited way? In answering this we should focus on real human judges, not Hercules. Perhaps it is enough to confer legitimacy if judges and other participants are seriously trying to achieve integrity. Through their efforts we attempt to be a community of principle, and enough success can be achieved to make those efforts meaningful. Perhaps the greatest integrity is achieved within the various legal compartments.