Sources of Demand - BYU Marriott School

advertisement

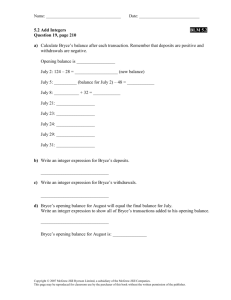

Sources of Demand MANEC 387 Economics of Strategy David J. Bryce David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 Exercise • I will name possible prices for a Reese’s • As I name a price, please tell me how many Reese’s you are willing to purchase at that price, right now. • This exercise is an offer to sell and it is real. I reserve the right to call in the cash from any individual at any time who indicates their willingness to buy (you can bring me the cash later if you don’t have it on hand!). David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 Class Demand For Reese’s $1.00 Price $0.75 $0.50 $0.25 $0.00 0 50 100 Quantity Demanded David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 150 Market Demand Curve • Shows the amount of a good that will be purchased at alternative prices. • Law of Demand – The demand curve is downward sloping. Price D Quantity David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 Determinants of Demand • • • • • • Income Prices of substitutes Prices of complements Advertising Population changes Consumer expectations David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 The Demand Function • An equation representing the demand curve Qxd = f(Px , PY , M, H,) – Qxd = quantity demand of good X. – Px = price of good X. – PY = price of a substitute good Y. – M = income. – H = any other variable affecting demand David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 Change in Quantity Demanded Price A to B: Increase in quantity demanded A 10 B 6 D0 4 David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 7 Quantity What could lead to a change in quantity demanded? • Only a change in price • Why? – Because a given demand curve simply reflects preferences under a given set of conditions—it is a picture of stationary preferences – When conditions change, preferences often do as well, so that the entire relationship of quantity to price also changes (shift in demand) David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 Change in Demand Price D0 to D1: Increase in Demand 6 D1 D0 7 David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 13 Quantity What could lead to an increase in demand (shift in demand)? • A change in any of the determinants of demand: – – – – – – Income Prices of substitutes Prices of complements Advertising Population changes Consumer expectations • A change in the quality or characteristics of a product, even if the changes are small David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 Where do demand curves come from? • Experiments – Raise and lower price systematically over time and watch what happens to quantity – Limitation: hard to control for changes in external factors (you may get a “wiggly” curve!) • Market Research – Surveys in which consumers are asked to tradeoff bundles of goods against price or other bundles in order to determine relative value and demand at given prices – Limitation: Expensive; sampling bias; perception bias— spending real money is different than checking boxes on a survey David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 Where do demand curves come from? • Regression analysis – Attempt to glean from multiple observations in multiple settings (geographic, store, product, etc.) the relationship between price and quantity • Not always goods that are exactly like • Do not always have observations on the extremes of the curve—extrapolation required – Must control for the amount supplied (otherwise may get an upward sloping demand curve!) – Limitation: Data is hard to get and you must assume that external factors are stable across observations or control for these in the statistics; CAUTION: If you don’t know what you’re doing, you could go wildly astray David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 Where do demand curves come from? • If all else fails – Use Intuition – “Sniff” the market by looking at how other similar products seem to be doing – Ask your close friends and neighbors how much they would pay – Pray about it (Limitation: faith) – Any other possible qualitative approach you can think of – Believe it or not, you’re likely to get close … and others are doing the same thing in practice • Bottom line: No technique is fool-proof! David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 Estimating a curve example: • A retailer wants to know the demand curve for ties – Observes that over the past 2 weeks 100 ties have sold at $25 – Reduces price to $20 for next two weeks without announcement; sells 120 ties – Reduces price to $15 for following two weeks; sells 160 ties David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 Estimating a curve example: Two Week Demand for Ties $30 $25 $20 Price of Ties Sold $15 $10 $5 $0 80 100 120 140 160 Quantity of Ties Sold David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 180 Estimating a curve example: 180 Two Week Demand for Ties 160 140 120 Quantity 100 of Ties 80 Sold 60 Q = -6P + 246.67 40 20 0 $10 $15 $20 $25 Price of Ties Sold David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 $30 Consumer Surplus – the value consumers get from a good but do not have to pay for • “I got a lousy deal!” • That car dealer drives a That company offers a lot hard bargain! of bang for the buck! • I almost decided not to buy it! Dell provides good value. • They tried to squeeze the Total value greatly very last cent from me! exceeds total amount • Total amount paid is close paid. to total value. Consumer surplus is large. • Consumer surplus is low. • “I got a great deal!” • • • • David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 Consumer Surplus: The Discrete Case Price 10 Consumer Surplus: the value received but not paid for 8 6 4 2 D 1 David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 2 3 4 5 Quantity Consumer Surplus: The Continuous Case Price $ 10 Value of 4 units 8 Consumer Surplus 6 Total Cost of 4 Units 4 2 D 1 David Bryce © 1996-2002 Adapted from Baye © 2002 2 3 4 5 Quantity