Deep Packet Inspection

advertisement

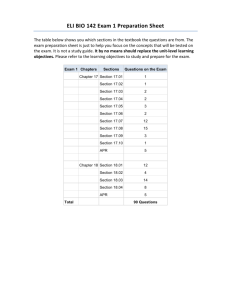

Matthew Carson CSC 540 Individual Research Project April 15, 2014 Deep Packet Inspection As more and more information is sent over the internet every day, many people are worried about the security of their information. According to Rick Burgess of TechSpot.com, “In just 60 seconds, nearly 640 terabytes of IP data is transferred across the globe” (Burgess). According to these figures, in an average day on the internet, nearly 900 petabytes are transferred. Burgess goes on to say, “in an Internet minute, Amazon rakes in around $83,000 in sales.” These figures are staggering to say the least, however, they definitely help shine light on the need for security measures on the internet today. The question then becomes, how should we secure the transfer of this enormous amount of information? In order to address the problems associated with information that is transmitted across the internet, many technologies have been developed which can monitor and, in some cases, intercept malicious data and software. These technologies are meant to protect personal information, both traversing the internet and on a user’s personal machine, by filtering out dangerous sources which may be attached to information which is being transmitted. However, in order to do this effectively, such software must have access to the very information, including personal and sensitive information, it was designed to protect. Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) is one such technology. Deep Packet Inspection works through the structure of how information is passed along the internet. When a user wants to transmit information through the internet, that information is broken up into several smaller pieces, or packets, of information. These packets are then numbered, and labeled corresponding to where they need to go while travelling across multiple networks, as well as how they should be reassembled once they arrive at their destination. This system can be thought of analogously to the current postal system. In a normal system, letters, packets, are sent through different post offices on the way to their destination. At each post office, the address of the recipient, packet header, is read, and then the letter is forwarded to the next post office on its journey. In contrast, a system involving DPI would be analogous to each post office opening the letters, reading the contents, and then sending them on to the next post office. This analogy is obviously very troubling, however, it stands to illustrate the fundamental flaw of Deep Packet Inspection. When the technology is used as per its original purpose (i.e. filtration of malicious content) there is no problem, however, where does security transcend into the realm of eavesdropping? Have you ever searched for a new topic online, and then, either that day or a few days from that moment, you begin to see ads for that exact thing everywhere you look online? Many internet users experience this phenomenon every day. When a person buys a new car, or learns some new random fact, several people claim to begin seeing many occurrences of that object every day. This phenomenon is known as the BaaderMeinhof Phenomenon (“There’s a Name for That”), and it can give the illusion that someone or something is keeping tabs on what you do. This same phenomenon happens repeatedly on the internet. The difference between the two occurrences is that on the internet, one really is being watched constantly. Facebook, the social media giant, is notorious for targeting advertisements to users based on their likes and previous posts. However, many users may notice ads which pertain directly to web sites they have visited previously, in some cases, even sites they visited for the first time on that day. Facebook uses persistent cookies placed in a browser, even when the site is just simply visited (Whitlock). Even when users simply disable browsing cookies, their information is still sent to Facebook. While this is not directly a result of Deep Packet Inspection (DPI technology) the underlying premise is still the same. In essence, users’ history is tracked and “sold” for advertising purposes, which many view as a violation of their personal privacy, which it very well may be. However, this very same principle of advertising is used by several advertising companies on the internet today in order to target advertising based on users’ history. Many companies today use DPI technology to ensure their customer’s information is secure. For example, Dell currently employs the use of a DPI technology known as Reassembly-Free Deep Packet Inspection (RFDPI) in order to protect their consumers from unwanted viruses, malware and attacks from a myriad of malicious sources (“Deep Packet Inspection”). On the opposite end of this spectrum, DPI technology is currently being used in China in order to monitor the populace’s movements on the internet, in an attempt to control the flow of information (Wawro). While these uses can be interpreted as benevolent actions in the attempt to protect consumers at large, there are many companies which use DPI technology for much more ethically nefarious purposes, one of these companies is NebuAd. In 2007, an internet service provider (ISP), known as Embarq, entered into an agreement with NebuAd, an online behavioral tracking start-up company in California. The agreement allowed NebuAd to collect information about the web browsing history of customer’s on Embarq’s networks. This information was then used to facilitate advertising targeted to individual consumers by NebuAd (Augustino, and Miller). Most would consider this action illegal, especially considering NebuAd retrieved this information without the express permission from the customers of Embarq (Austin). This case, however, is not as clear cut in terms of the law. The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 prohibits the interception of electronic communications unless covered under a legal subpoena, and is the standard legal argument when it comes to questions regarding privacy and the use of technology as an electronic medium for communication. Several plaintiffs brought legal action against Embarq, citing that Embarq violated the terms of the ECPA in allowing NebuAd to collect information about their customer’s without their express consent. On the surface, this argument appears solid, however, the courts upheld that Embarq was not liable for any violation of privacy. This ruling was upheld based upon the blurred line between the definition of access and acquisition. The ECPA prohibits the “interception” of electronic messages, which the court upheld as the “acquisition” of the content of the information in question (Balasubramani). In this respect, Embarq did not “acquire” the information, as much as they had access to the information, therefore, they did not directly violate the terms of the ECPA. But what happened to NebuAd. Most would probably agree that the collection of information about individuals, barring the existence of a subpoena, without that individual’s consent is at the very least unethical. This is evident by the actions of many of NebuAd’s affiliated Internet Service Providers. According to Wikipedia, several of the ISP’s who used NebuAd’s technology for behavioral advertising ended their dealings with the company well before the lawsuits began. Many of these companies are cited as withdrawing due to “concerns regarding privacy issues” (Wikipedia). Despite the multitude of warning markers, NebuAd continued to assert that it was innocent of any wrong doing and that it “aggressively notified Internet subscribers about the monitoring and giving them a chance to opt out” (Austin). These assertions are not quite as “aggressive” as the statements by NebuAd would lead one to believe. According to Ars Technica, in order to notify their users about their use of NebuAd’s technology, Embarq purportedly inserted a two paragraph statement into their 5,000-word privacy policy informing their users about the changes (Anderson). With such an important change as monitoring the entirety of their user’s web browsing, one would expect something more direct than an abstract entry into an already exhaustive privacy policy. Statistics from Ars Technica show just how effective this informative technique proved to be. “Out of Embarq's 26,000 Internet customers in the Gardner area, only 15 opted out. That 0.06 percent of the total, which means that 99.94 percent of subscribers really did love the "enhancement" they got from the NebuAd service—either that or they had no idea that their ISP data was being mined to construct anonymous ad categories.” (Anderson) Even more troubling is the fact that, even should a user choose to “opt-out” of the NebuAd advertising, their data is still not safe. According to Ryan Singel of Wired.com, the opt-out program of NebuAd involves the use of an “opt-out cookie” which still will not stop the technology from logging a user’s data (Singel). Charter Communications, which was in the preliminary stages of implementing NebuAd’s technology at the time, refused to say that the opt-out program would keep the user’s information from being tracked, rather they stated that a user who opts out, “will no longer receive ads that are tailored to your web preferences, usage patterns and commercial interests” (Singel). Thus, regardless of whether a user on a network provided by an ISP affiliated with NebuAd opts out of the service, their data would still be collected. NebuAd subsequently closed down operations in May of 2009 and has agreed to a settlement of $2.4 million in favor of the web users who brought suit against it and six ISP’s (Davis). Despite some of these gray area cases, Deep Packet Inspection is not an evil technology by any means. DPI can be used for many benevolent purposes without compromising the information of users. Some of these purposes include network security, copyright enforcement, as well as the lawful interception of information in aid of the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA). As was stated above, the ECPA prohibits the interception of electronic messages barring the presence of a legal subpoena, thus, Deep Packet Inspection is a vital tool to law enforcement officials in the pursuit of criminals, both online and off. CALEA affirms: “to make clear a telecommunications carrier's duty to cooperate in the interception of communications for Law Enforcement purposes, and for other purposes” ("Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act"). In today’s world, where a lot of messaging takes place over internet traffic (i.e. yahoo messaging, Facebook messaging, etc.) DPI technology is vital to the assistance of law enforcement agencies in order to monitor potentially criminal activity. As with many major technologies of today, Deep Packet Inspection occupies an area of major gray area where the defining line is the intent of the user of such technology. DPI technology offers a powerful medium of control and security when used properly, just as it provides a myriad of exploitative functionality. As the future of technology develops and attacks on personal information and security continue to become more prevalent as well as increasingly technical in nature, the need for more advanced forms of monitoring such as Deep Packet Inspection will become ever more necessary. References 1. "Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act." Wikipedia. Wikipedia, 110 Apr 2014. Web. 14 Apr 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communications_Assistance_for_Law_Enforc ement_Act>. 2. "Deep Packet Inspection." Dell SonicWALL, Inc.. Open Text Web Solutions. Web. 13 Apr 2014. <https://www.sonicwall.com/us/en/products/DeepPacket-Inspection.html> 3. "NebuAd." Wikipedia. Wikipedia, 5 Apr 2014. Web. 13 Apr 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NebuAd>. 4. "There’s a Name for That: The Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon." Pacific Standard. Pacific Standard, 22 July 2013. Web. 14 Apr. 2014. <http://www.psmag.com/culture/theres-a-name-for-that-the-baadermeinhof-phenomenon-59670/>. 5. Anderson, Nate. ".06% opt out: NebuAd hides link in 5,000-word privacy policy." Ars Technica. Ars Technica, 24 Jul 2008. Web. 13 Apr 2014. <http://arstechnica.com/uncategorized/2008/07/06-opt-out-nebuad-hideslink-in-5000-word-privacy-policy/>. 6. Augustino, Steve, and Barbara Miller. "Court Rules for ISP in Deep Packet Inspection Lawsuit." Telecom Law Monitor. Telecom Law Monitor, 7 Jan 2013. Web. 14 Apr 2014. <http://www.telecomlawmonitor.com/2013/01/articles/litigation/courtrules-for-isp-in-deep-packet-inspection-lawsuit/>. 7. Austin, Scott. "Turning Out The Lights: NebuAd." Venture Capital Dispatch - The Wall Street Journal. The Wall Street Journal, 19 May 2009. Web. 13 Apr 2014. <http://blogs.wsj.com/venturecapital/2009/05/19/turning-out-thelights-nebuad/>. 8. Balasubramani, Venkat. "Privacy Plaintiffs in Deep Packet Inspection Case Get No Love From the Tenth Circuit -- Kirch v. Embarq Management." Technology & Marketing Law Blog. Technology & Marketing Law Blog, 7 Jan 2013. Web. 13 Apr 2014. <http://blog.ericgoldman.org/archives/2013/01/tenth_circuit_g_1.htm>. 9. Burgess, Rick. "One minute on the Internet: 640TB data transferred, 100k tweets, 204 million e- mails sent." TechSpot. TechSpot, 20 Mar 2013. Web. 13 Apr 2014. <http://www.techspot.com/news/52011-one-minute-on-the-internet640tb-data-transferred-100k-tweets-204-million-e-mails-sent.html>. 10. Davis, Wendy. "NebuAd Settles Lawsuit Over Behavioral Targeting Tests." MediaPost Publications. MediaPost Publications, 16 Aug 2011. Web. 14 Apr 2014. <http://www.mediapost.com/publications/article/155980/>. 11. Singel, Ryan. "Can Charter Broadband Customers Really Opt-Out of Spying? Maybe Not." Wired. Wired, 16 May 2008. Web. 14 Apr 2014. <http://www.wired.com/2008/05/theres-no-optin/>. 12. Wawro, Alex. "What Is Deep Packet Inspection?" PCWorld. PCWorld, 1 Feb 2012. Web. 13 Apr 2014. <http://www.pcworld.com/article/249137/what_is_deep_packet_inspection _.html>. 13. Whitlock, Tim. "Is Facebook tracking your web browsing history?." timwhitlock. N.p., 7 Jan. 2011. Web. 14 Apr. 2014. <http://timwhitlock.info/blog/2011/01/is-facebook-tracking-your-webbrowsing-history/>.