1 mol H

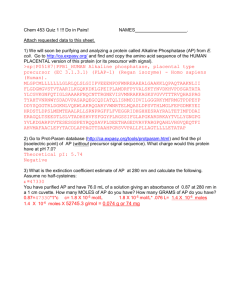

advertisement

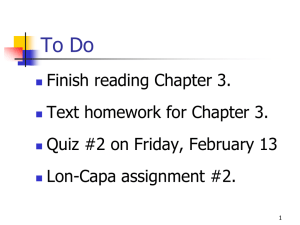

Homework Problems Chapter 3 Homework Problems: 2, 6 (a,b), 10, 24, 31, 34, 40, 44 (a,b), 50, 52, 54, 56, 64, 70, 76, 80, 84, 88, 92, 94, 100, 106, 116, 128 CHAPTER 3 Stoichiometry: Ratios of Combination Molecular Mass and Formula Mass The molecular mass (M) of a substance is the average mass of one molecule of the substance. For substances that do not exist as molecules, such as ionic compounds, we use the formula mass, which represents the average mass of one formula unit of the compound. Example: Find the formula mass for potassium chloride (KCl). KCl K 1 . 39.0983 amu = 39.0983 amu Cl 1 . 35.453 amu = 35.453 amu M = 74.551 amu 74.55 amu We often round off molecular mass or formula mass to two places to the right of the decimal point. Percent By Mass The percent by mass represents the percentage of each element present in a sample of a pure chemical substance. The percent by mass of a particular element is simply the mass of that element found in one molecule (formula unit) divided by the total mass of the molecule (or formula unit), converted to a percentage by multiplying by 100%. percent X by mass = mass of X • 100% formula mass Note that the sum of the percent by mass of each element present in a substance should be equal to 100% (to within roundoff error). Example: What is the molecular mass, and the percent by mass of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, in propionaldehyde (C3H6O)? Example: What is the molecular mass, and the percent by mass of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, in propionaldehyde (C3H6O)? First step: Find the average mass of each element per molecule and the average mass per molecule (or formula unit). C3H6O C H O 3 . 12.0107 amu 6 . 1.00794 amu 1 . 15.9994 amu = 36.0321 amu = 6.04764 amu = 15.9994 amu M = 58.0791 amu 58.08 amu Second step: Find the percent composition. C3H6O C H O 3 . 12.0107 amu 6 . 1.00794 amu 1 . 15.9994 amu = 36.0321 amu = 6.04764 amu = 15.9994 amu M = 58.0791 amu 58.08 amu % C by mass = 36.0321 amu • 100% = 62.04 % C by mass 58.0791 amu % H by mass = 6.04764 amu • 100% = 10.41 % H by mass 58.0791 amu % O by mass = 15.9994 amu • 100% = 27.55 % O by mass 58.0791 amu Note 62.04% + 10.41% + 27.55% = 100.00%, as expected. Use of Percent Composition as a Conversion Factor The percent composition of a chemical substance can be used as a conversion factor in calculations. Example: Titanium metal is often extracted from rutile, an ore that is 59.9 % titanium by mass. What mass of rutile would be needed to produce 100.0 kg of titanium metal? Example: Titanium metal is often extracted from rutile, an ore that is 59.9 % titanium by mass. What mass of rutile would be needed to produce 100.0 kg of titanium metal? The percent composition tells us that for every 100.0 kg of rutile we will have 59.9 kg of titanium. Therefore kg rutile = 100.0 kg Ti 100.0 kg rutile = 167. kg rutile 59.9 kg Ti Balanced Chemical Equation A balanced chemical equation indicates the starting substances (reactants) and ending substances (products) of a chemical reaction. The reactions may also indicate the state of the reactants and products, and/or the physical process used in the reaction. s = solid = liquid g = gas aq = aqueous = heat A balanced equation must satisfy conservation of mass (same number of atoms of each element on the reactant and product side) and conservation of electrical charge (same total charge on the reactant and product side). Examples of Balanced Chemical Equation Combustion of hydrogen (combustion is the reaction of a substance with molecular oxygen to form combustion products). 2 H2(g) + O2(g) 2 H2O() Nitration of toluene to form trinitrotoluene (TNT) C6H5CH3 + 3 HNO3 C6H2CH3(NO2)3 + 3 H2O Decomposition of calcium carbonate (decomposition is the breakdown of a single reactant into two or more products). CaCO3(s) CaO(s) + CO2(g) Dissolution of potassium sulfate, an ionic compound, in water. K2SO4(s) H2O 2 K+(aq) + SO42-(aq) Procedure For Balancing Chemical Equations 1) Begin with a complete set of reactants and products. These cannot be changed. 2) Find a set of numbers (stoichiometric coefficients) that satisfy mass balance. a) Change the coefficients of compounds before changing the coefficients of elements (save elements for last in balancing). b) Treat polyatomic ions that appear on both sides of the equation as a unit. c) Count atoms and polyatomic ions carefully, and track them every time you change a coefficient. Procedure For Balancing Chemical Equations 3) Convert the stoichiometric coefficients into the smallest set of whole numbers that correctly balance the chemical equation. 1/ 2 N2 + 3/2 H2 NH3 incorrect; fractional coefficient N2 + 3 H2 2 NH3 correct 2 N2 + 6 H2 4 NH3 incorrect; not smallest set of whole numbers This step can be saved for last. Remember that if a chemical equation is correctly balanced then multiplying all of the coefficients by the same number results in an equation that is also balanced. Later in the semester we will come across a few cases where we do sometimes use fractional coefficients to balance chemical equations. Example: Balance the following unbalanced chemical equation for the combustion of iso-octane, a hydrocarbon used to determine the octane rating of gasoline C8H18 + O2 CO2 + H2O (unbalanced) Combustion of Iso-octane unbalanced C8H18 + O2 CO2 + H2O balance for C C8H18 + O2 8 CO2 + H2O balance for H C8H18 + O2 8 CO2 + 9 H2O balance for O C8H18 + 25/2 O2 8 CO2 + 9 H2O convert to whole numbers (multiply through by 2) 2 C8H18 + 25 O2 16 CO2 + 18 H2O Example - Precipitation of Lead (II) Chloride Precipitation reaction - A reaction where two soluble compounds are mixed and a solid product is formed. Pb(NO3)2(aq) + NaCl(aq) PbCl2(s) + NaNO3(aq) (unbalanced) Example - Precipitation of Lead (II) Chloride unbalanced Pb(NO3)2(aq) + NaCl(aq) PbCl2(s) + NaNO3(aq) balance for Cl Pb(NO3)2(aq) + 2 NaCl(aq) PbCl2(s) + NaNO3(aq) Balancing for Cl has now caused the above reaction to be unbalanced for Na. So we go back and rebalance for Na Pb(NO3)2(aq) + 2 NaCl(aq) PbCl2(s) + 2 NaNO3(aq) The above is now balanced. Remember that when you have a cation or anion group (such as NO3- above) it is often easier to balance equations treating this group as a unit. The Mole It is nearly impossible to work with individual atoms in the laboratory because of their small size and mass. For example, one 12C atom has a mass of 1.993 x 10-26 kg, far to small to measure directly with an analytical balance.. It is convenient to have a unit representing a number of atoms that can easily be measured by the usual techniques in the laboratory. This unit is called the mole. Avogardo’s Number The unit mole is simply a number. By definition, one mole of anything is equal to Avogadro’s number of things. Avogadro’s number, an experimentally determined quantity is NA = 6.022 x 1023. Note that there is no difference between the concept of moles and more common terms used for specific numbers of things. 1 dozen = 12 1 score = 20 1 thousand = 1000 1 mole = 6.022 x 1023 Example (Avogadro’s Number) If I have three dozen eggs, then how many eggs do I have? 1 dozen eggs = 12 eggs (a conversion factor) number of eggs = 3 dozen eggs 12 eggs = 36 eggs 1 dozen If I have three moles of carbon atoms, then how many carbon atoms do I have 1 mole carbon atoms = 6.022 x 1023 carbon atoms number of carbon atoms = 3 moles C 6.022 x 1023 C atoms 1 mole = 1.81 x 1024 carbon atoms Moles is the fundamental SI unit for quantity of substance. The symbol for moles is n, and the abbreviation for the unit moles is mol. Significance of Avogadro’s Number There must be something special about the number 6.022 x 1023 (Avogadro’s number). The significance is as follows. Consider a collection of identical objects. The following relationship will apply. If one object has a mass of X amu… …then one mole of objects has a mass of X g. This is a subtle point. Consider the unit “thousand”. We could make the following statement If one object has a mass of X g… …then one thousand objects has a mass of X kg. Example: The mass of one penny is 2.50 g. The mass of one thousand pennies is mass one thousand pennies = 1000 (2.50 g) = 2500. g 1 kg = 2.50 kg The same principle applies to the concept of moles mass of one 19F atom = 19.00 amu, so mass of one mole of 19F atoms = 19.00 g. Check mass one mole 19F = (6.022 x 1023) (19.00 amu) = 1.1442 x 1025 amu 1.6605 x 10-27 kg 1 amu = 0.01900 kg = 19.00 g Use of the Mole Concept 1) We may use the concept of moles to reinterpret atomic mass. Atomic mass of S = 32.06 amu = 32.06 g/mol We interpret the atomic mass of sulfur (or any other element in the periodic table) in two equivalent ways: The average mass of one sulfur atom is 32.06 amu. The mass of one mole of sulfur atoms is 32.06 g. Use of the Mole Concept 2) We may use the concept of moles to reinterpret a balanced chemical equation CH4(g) + 2 O2(g) CO2(g) + 2 H2O() We interpret the balanced chemical equation in two equivalent ways: One molecule of methane reacts with two molecules of molecular oxygen to form one molecule of carbon dioxide and two molecules of water. One mole of methane reacts with two moles of molecular oxygen to form one mole of carbon dioxide and two moles of water. Note that when the mole concept is used fractional coefficients make sense. Use of the Mole Concept (Example) A chemist has a 14.38 g sample of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4). a) How many moles of CCl4 does she have? b) How many atoms of C and Cl are present in the sample? Use of the Mole Concept (Example) A chemist has a 14.38 g sample of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4). a) How many moles of CCl4 does she have? CCl4 C Cl 1 . 12.0107 amu 4 . 35.453 amu = 12.0107 amu = 141.81 amu M = 153.82 amu = 153.82 g/mol Moles CCl4 = 14.38 g 1 mol = 0.09349 mol CCl4 153.82 g = 9.349 x 10-2 mol CCl4 Use of the Mole Concept (Example) b) How many atoms of C and Cl are present in the sample? # C atoms = 9.349 x 10-2 mol CCl4 1 mol C 6.022 x 1023 atoms C 1 mol CCl4 mol = 5.630 x 1022 C atoms # Cl atoms = 9.349 x 10-2 mol CCl4 4 mol Cl 6.022 x 1023 atoms C 1 mol CCl4 mol = 2.252 x 1023 Cl atoms Experimental Determination of the Empirical Formula The empirical formula for a pure substance can be found if we know either the percent composition of the substance (percent by mass of each element making up the substance) or the mass of each element present in a sample of the substance of known mass. The general procedure we use is as follows: 1) Determine the number of moles of each element present in a sample of the substance (if you know the percent by mass of each element it is convenient to assume 100.0 g of the substance). 2) Divide the results by whichever number of moles is smallest. This will give you the number of moles of each element relative to this smallest number of moles. 3) Convert the relative number of moles into the smallest set of whole number coefficients. This may require multiplication by a small whole number (2, 3, …). Example: A 3.862 g sample of a pure chemical substance was analyzed and found to contain three elements in the following amounts. Cobalt (Co) 1.245 g Nitrogen (N) 0.587 g Oxygen (O) 2.030 g What is the empirical formula of the substance? Cobalt (Co) 1.245 g Nitrogen (N) 0.587 g Oxygen (O) 2.030 g 1) Find the number of moles of each element. moles Co = 1.245 g Co 1 mol = 0.02113 mol Co 58.93 g moles N = 0.587 g N 1 mol = 0.0419 mol N 14.01 g moles O = 2.030 g O 1 mol = 0.1269 mol O 16.00 g 2) Divide through by the smallest number of moles (0.02113) rel. moles Co = 0.02113 = 1.000 0.02113 rel. moles N = 0.0419 = 1.98 0.02113 rel. moles O = 0.1269 = 6.006 0.02113 3) Since these numbers are close to being integer values, the empirical formula is CoN2O6 (actually Co(NO3)2, cobalt (II) nitrate) Non-Integer Relative Amounts If the relative amounts of each element present are not close to integers, try multiplying all of the relative amounts by a small whole number (2, 3, or 4). If this gives integer values for the relative amounts of each element present, these values represent the empirical formula. Example: A compound containing chromium, oxygen, and potassium was analyzed, and the following percentages by mass for each element were found. Cr 35.35% O 37.99% K 26.66% What is the empirical formula for the compound? Example: A compound containing chromium, oxygen, and potassium was analyzed, and the following percentages by mass for each element were found. Cr 35.35% O 37.99% K 26.66% What is the empirical formula for the compound? Assume 100.0 g of compound. Then moles Cr = 35.35 g Cr 1 mol = 0.6798 mol Cr 52.00 g moles O = 37.99 g O 1 mol = 2.374 mol O 16.00 g moles K = 26.66 g K 1 mol = 0.6818 mol K 39.10 g Divide through by the smallest number of moles to get the relative number of moles of each element present rel moles Cr = 0.6798 mol = 1.000 0.6798 mol rel moles O = 2.374 mol = 3.492 0.6798 mol rel moles K = 0.6818 mol = 1.003 0.6798 mol Since these are not close to integer values, try multiplying by 2 rel mol Cr = 2.000 rel mol O = 6.984 rel mol K = 2.006 So the empirical formula is Cr2O7K2 (actually K2Cr2O7, potassium dichromate) Combustion Analysis Combustion analysis is a method often used in the analysis of organic compounds. A sample of the compound is allowed to completely react with oxygen and the mass of carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O) produced is measured. From this information the number of grams and the number of moles of carbon and hydrogen originally in the sample can be found. Combustion Analysis (Hydrocarbons) Combustion analysis can be carried out for hydrocarbons (compounds containing only carbon and hydrogen). This is because all of the carbon originally present in the compound is converted into CO2, and all of the hydrogen is converted into H2O. Example: C8H16 + 12 O2 8 CO2 + 8 H2O By knowing the mass of carbon dioxide and water formed by combustion, the mass and moles of carbon and hydrogen in the original compound can be found. From this, the empirical formula can be determined. Example: A pure hydrocarbon is analyzed by combustion analysis. Combustion of a sample of the hydrocarbon produces 3.65 g CO2 and 1.99 g H2O. What is the empirical formula for the hydrocarbon? Note: M(CO2) = 44.01 g/mol; M(H2O) = 18.02 g/mol. Example: A pure hydrocarbon is analyzed by combustion analysis. Combustion of a sample of the hydrocarbon produces 3.65 g CO2 and 1.99 g H2O. What is the empirical formula for the hydrocarbon? Note: M(CO2) = 44.01 g/mol; M(H2O) = 18.02 g/mol. moles C = 3.65 g CO2 1 mol CO2 1 mol C = 0.0829 mol C 44.01 g CO2 1 mol CO2 moles H = 1.99 g H2O 1 mol H2O 2 mol H = 0.221 mol H 18.02 g H2O 1 mol H2O relative moles C = 0.0829 mol/0.0829 mol = 1.00 relative moles H = 0.221 mol/0.0829 mol = 2.67 To get values close to integers multiply by 3. Empirical formula = C3H8 (3.00) (8.00) Combustion Analysis (C, H, and O Present) For a compound containing carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, combustion analysis is more complicated. That is because some of the oxygen in the combustion products comes from the compound, and some of the oxygen comes from the O2 used to carry out the combustion. Example: C6H12O6 + 6 O2 6 CO2 + 6 H2O While all of the carbon and hydrogen in the combustion products comes from the original compound, some of the oxygen comes from the molecular oxygen used to carry out the combustion reaction. Combustion Analysis (C, H, and O Present) To do combustion analysis for a compound in this case requires knowing the total mass of compound burned. Since mtotal = mC + mH + mO Then mO = mtotal – (mC + mH) The grams (and moles) of carbon and hydrogen present in the compound are found as before. We can then use the above equation to find the grams and moles of oxygen, and, from that, the empirical formula for the compound. Finding the Molecular Formula From the Empirical Formula As previously discussed, there is a relationship between the empirical formula and the molecular formula for the substance. (molecular formula) = N (empirical formula) where N is an integer (1, 2, 3, …) Substance Molecular formula Empirical formula N propane C4H10 C2H5 2 sulfuric acid H2SO4 H2SO4 1 CH2 6 cyclohexane C6H12 Finding the Molecular Formula From the Empirical Formula Since (molecular formula) = N (empirical formula) N = 1, 2, 3, … Then N = mass of molecular formula mass of empirical formula So if we can find the empirical formula and the mass of the molecule we can find N, and from that the molecular formula. Example: The empirical formula for a substance is CH2O. The molecular mass of the substance is 60. g/mol. What is the molecular formula for the substance? Finding the Molecular Formula From the Empirical Formula Example: The empirical formula for a substance is CH2O. The molecular mass of the substance is 60. g/mol. What is the molecular formula for the substance? N = mass of molecular formula mass of empirical formula The mass of the empirical formula is M(empirical) = 1 (12.01 g/mol) + 2 (1.008 g/mol) + 1 (16.00 g/mol) = 30.03 g/mol N = 60. g/mol = 2.0 2 30.03 g/mol So the molecular formula is C2H4O2. Interpretation of Chemical Equations Consider the equation for the formation of water from hydrogen and oxygen, discussed previously. 2 H2(g) + O2(g) 2 H2O() We can interpret this equation in two ways: 1) Two molecules of hydrogen and one molecule of oxygen combine to form two molecules of water. 2) Two moles of hydrogen and one mole of oxygen combine to form two moles of water. Note that the second interpretation makes sense even if we have fractional stoichiometric coefficients. One of the most important uses of a balanced chemical equation is to provide the information needed to convert from the amount of one substance inolved in a reaction and the amount of a second substance that is required for the reaction. Example: Consider the following balanced chemical equation 2 H2(g) + O2(g) 2 H2O() If we begin with 4.8 moles of H2, how many moles of O2 will be required for a complete reaction? What is the maximum number of moles of H2O that we will be able to produce? Example: Consider the following balanced chemical equation 2 H2(g) + O2(g) 2 H2O() If we begin with 4.8 moles of H2, how many moles of O2 will be required for a complete reaction? What is the maximum number of moles of H2O that we will be able to produce? mol O2 = 4.8 mol H2 1 mol O2 = 2.4 mol O2 2 mol H2 mol H2O = 4.8 mol H2 2 mol H2O = 4.8 mol H2O 2 mol H2 Example: reaction occurs. When sodium metal is placed in water a violent 2 Na(s) + 2 H2O() 2 NaOH(aq) + H2(g) If we begin with 4.0 moles of sodium metal, how many moles of water are required to completely react with the sodium metal? How many moles of hydrogen gas will form? 2 Na(s) + 2 H2O() 2 NaOH(aq) + H2(g) If we begin with 4.0 moles of sodium metal, how many moles of water are required to completely react with the sodium metal? How many moles of hydrogen gas will form? mol H2O = 4.0 mol Na 2 mol H2O = 4.0 mol H2O 2 mol Na mol H2 = 4.0 mol Na 1 mol H2 = 2.0 mol H2 2 mol Na Calculations Using Mass of Reactants and Products In the laboratory we work with masses of reactants and products. However, as we have seen, chemical equations give relationships among moles of reactants and products. We therefore need a method for going back and forth between moles of substance and grams of substance. We may do this conversion using M, the molecular mass or formula mass of a substance. For example, the molecular mass of ethane (C2H6) is M(C2H6) = 30.07 g/mol This is a conversion factor between mass of C2H6 and moles of C2H6. Strategy For Calculations Using Balanced Chemical Equations We may use the following strategy to find the mass of reactant or product in a chemical equation. 1) Convert from grams of the first substance into moles of the first substance using the molecular mass of the substance. 2) Use the balanced chemical equation to find the correct number of moles of the second substance. 3) Convert from number of moles of the second substance to mass of the second substance using the molecular mass of the substance. Example We can use a balanced chemical equation and our new concept of moles to do calculations involving chemical reactions. Example: Calcium chloride (CaCl2) can be produced by the reaction of hydrochloric acid (HCl) and calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2). 2 HCl + Ca(OH)2 CaCl2 + 2 H2O In a particular reaction we begin with 10.00 g HCl. How many grams of Ca(OH)2 are required to completely react with this amount of HCl? How many grams of calcium chloride can be produced by the reaction? calcium chloride 2 HCl + Ca(OH)2 CaCl2 + 2 H2O In a particular reaction we begin with 10.00 g HCl. How many grams of Ca(OH)2 are required to completely react with this amount of HCl? How many grams of calcium chloride can be produced by the reaction? M(HCl) = 36.46 g/mol M(CaCl2) = 110.98 g/mol M(Ca(OH)2) = 74.09 g/mol M(H2O) = 18.02 g/mol 1) Find the moles of HCl. n(HCl) = 10.00 g HCl 1 mol HCl 36.46 g HCl = 0.2743 mol HCl 2) Find the moles Ca(OH)2. n(Ca(OH)2) = 0.2743 mol HCl 1 mol Ca(OH)2 = 0.1371 mol Ca(OH)2 2 mol HCl 3) Find the grams of Ca(OH)2 m(Ca(OH)2) = 0.1371 mol Ca(OH)2 74.09 g Ca(OH)2 = 10.16 g 1 mol Ca(OH)2 We can also find the mass of calcium chloride that can be produced by the reaction m(CaCl2) = 0.2743 mol HCl 1 mol CaCl2 110.98 g CaCl2 2 mol HCl 1 mol CaCl2 = 15.22 g CaCl2 Yields For a Chemical Reaction There are three types of yields we can define for a chemical reaction. Theoretical yield - The maximum amount of product that can be formed from the starting materials used in the reaction. Actual yield - The observed yield for a chemical reaction. Percent yield - The percent of the theoretical yield that is actually obtained. . 100% % yield = actual yield theoretical yield For example, if the amount of CaCl2 actually obtained in the above reaction was 11.46 g, then the percent yield for the reaction would be % yield = 11.46 g . 100% = 75.3 % 15.22 g Limiting Reactant In most chemical reactions several reactants combine to form products. As soon as one of the reactants runs out, the reaction will stop, even if the other reactants are still present. We define the limiting reactant as the reactant the first runs out in a chemical reaction. Note that the theoretical yield of product is determined by the limiting reactant. Example: Consider making sandwiches out of cheese and bread. One sandwich consists of two slides of bread and one slice of cheese. If we begin with 10 slices of bread and 3 slices of cheese, what is the “limiting reactant” and the “theoretical yield” of cheese sandwiches? 2 slices bread + 1 slice cheese 1 cheese sandwich Start with 10 slices bread 3 slices cheese “limiting reactant” = cheese “theoretical yield” = 3 sandwiches “excess reactant” = bread Example: Methane can be formed by reacting carbon and hydrogen. If we begin with 3 carbon atoms and 10 hydrogen molecules, what is the limiting reactant, the excess reactant, and the theoretical yield of methane? The balanced equation is C + 2 H2 CH4 limiting reactant = carbon excess reactant = hydrogen theoretical yield = 3 methane molecules Note this works equally well if done in terms of moles. Finding the Limiting Reactant For a reaction involving two reactants (A and B) the limiting reactant can be found as follows. 1) Find the number of moles of A and B. 2) a) Find the number of moles of product that can be formed from reactant A, assuming it is the limiting reactant b) Find the number of moles of product that can be formed from reactant B, assuming it is the limiting reactant 3) Whichever number of moles of product is smallest corresponds to the limiting reactant. The other reactant is in excess. The smallest number of moles corresponds to the theoretical yield of product. The advantage of the above process is that it works no matter how many reactants there are in the reaction. Example: Consider the following chemical reaction (molecular masses are given below each reactant). C2H2 (26.04 g/mol) + 2 HCl (36.46 g/mol) C2H4Cl2 (98.96 g/mol) In a particular experiment we begin with 10.00 g C2H2 and 20.00 g HCl. What is the limiting reactant and the theoretical yield of C2H4Cl2? C2H2 (26.04 g/mol) + 2 HCl (36.46 g/mol) C2H4Cl2 (98.96 g/mol) In a particular experiment we begin with 10.00 g C2H2 and 20.00 g HCl. What is the limiting reactant and the theoretical yield of C2H4Cl2? moles C2H2 = 10.00 g 1 mol = 0.3840 mol C2H2 26.04 g moles HCl = 20.00 g 1 mol = 0.5485 mol HCl 36.46 g Moles C2H4Cl2 that could be produced if C2H2 is limiting moles C2H4Cl2 = 0.3840 mol C2H2 1 mol C2H4Cl2 = 0.3840 mol 1 mol C2H2 Moles C2H4Cl2 that could be produced in HCl is limiting moles C2H4Cl2 = 0.5485 mol HCl 1 mol C2H4Cl2 = 0.2743 mol 2 mol HCl The smallest number of moles corresponds to HCl. Therefore: HCl is the limiting reactant C2H2 is in excess The theoretical yield of C2H4Cl2 is 0.2743 mol We can now use the molecular mass of C2H4Cl2 to convert the theoretical yield into grams of product. Theoretical yield (grams) = 0.2743 mol C2H4Cl2 98.96 g C2H4Cl2 = 27.14 g C2H4Cl2 1 mol C2H4Cl2 Types of Chemical Reactions There are literally thousands of different types of chemical reactions. Three common types are: Combination reaction - Two or more reactants form a single product. C(s) + O2(g) CO2(g) Decomposition reaction - A single reactant forms two or more products. CuSO4 • 5 H2O(s) CuSO4(s) + 5 H2O(g) Combustion reaction - Reaction of a single substance with molecular oxygen to form combustion products (CO2(g), H2O(l). C3H8(g) + 5 O2(g) 3 CO2(g) + 4 H2O(l) End of Chapter 3 “I have lived much of my life among molecules. They are good company.” - George Wald “The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not Eureka! (I found it!) but rather, ‘hmm.... that's funny.…’” - Isaac Asimov “…it has become hard to find an important problem (in science) that is not already being worked on by crowds of people on several continents.” - Max Perutz “Not everyone learns from books.” - Sheila Rowbothum, Resistance and Revolution