Topicality Non-Traditional Activity

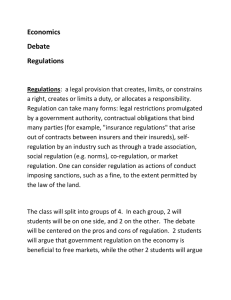

advertisement