Chapter 11 The Mathematics of Chemical Equations

Chapter 11

“The Mathematics of Chemical

Equations”

What quantitative relationships exist between reactants & products?

Chapt. 11 OBJECTIVES

Define “stoichiometry” & describe its importance.

Relate stoichiometry to balanced chemical equations.

Identify & learn to solve different types of stoichiometry problems.

Determine the “limiting reactant” (or “limiting reagent”) of a chemical reaction.

Calculate the amount of product that forms when reactants are present in proportions.

nonstoichiometric

Determine ‘percent yield’ of a chemical reaction.

11-1 STOICHIOMETRY

What is it?

The quantitative study of chemistry!

Comes from the Greek: “ stoichion” (element) &

“metron” (measure).

Includes what we studied in Chapter 10, plus the relationships between reactants & products in balanced chemical equations.

Is stoichiometry important?

YES! It is a vital part of ‘real-world’ manufacturing chemistry.

INTERPRETING BALANCED

CHEMICAL EQUATIONS

Write the equation with correct formulas, and balance it.

The coefficients relate to n molecules, or 2n, 7n, 100n,

2000n or even Avogadro’s number of molecules!

The coefficients also relate to the moles of molecules!

Summary: Coefficients in balanced chemical equations may be interpreted in terms of the relative number of particles involved in the reaction (atoms, molecules, ions, formula units)

AND as the relative number of moles.

INTERPRETING BALANCED CHEMICAL

EQUATIONS: Mole-Mole Problems

Convert from moles of one substance to moles of another in the balanced chemical equation.

Makes use of molar ratios.

Example:

How many moles of HCl are needed to react with

5.70 moles of Zn by the reaction

2HCl + Zn ZnCl

2

+ H

2

5.70 mol Zn X (2 mol HCl)/(1 mol Zn) = 11.4 mol HCl

Be careful with factor labels!

How does a balanced chemical equation relate to the “Law of Conservation of Matter” ?

11-2 Solving Stoichiometry

Problems

In Chapter 10 we learned how to use the mole to interconvert among numbers of particles, mass and volume for a given chemical formula.

Now we will use these ideas in combination with balanced chemical equations to solve stoichiometry problems.

The main types of problems are

Mass-Mass

Mass-Volume

Volume-Volume

The Keys…

…to solving Stoichiometry problems are…

…the Molar Ratio,

…the Mole

& Factor Labels!

Solving Stoichiometry Problems

QUANTITY

OF

“GIVEN”

QUANTITY

OF

“UNKNOWN”

MOLES

OF

“GIVEN”

CONVERT

TO MOLES

CONVERT

TO UNITS

NEEDED

USE MOLAR RATIO

(FROM BALANCED

CHEMICAL EQUATION)

MOLES

OF

“UNKNOWN”

Solving Mass-Mass Problems

MASS

OF

“GIVEN”

MOLES

OF

“GIVEN”

CONVERT

TO MOLES

(MOLAR MASS

“GIVEN”)

USE MOLAR RATIO

(FROM BALANCED

CHEMICAL EQUATION)

MASS

OF

“UNKNOWN”

CONVERT

TO MASS

(MOLAR MASS

“UNKNOWN”)

MOLES

OF

“UNKNOWN”

Solving Mass-Volume Problems

MASS

OF

“GIVEN”

MOLES

OF

“GIVEN”

CONVERT

TO MOLES

(MOLAR MASS

“GIVEN”)

USE MOLAR RATIO

(FROM BALANCED

CHEMICAL EQUATION)

VOLUME

OF

“UNKNOWN”

GAS

CONVERT

TO VOLUME

(GAS MOLAR

VOLUME)

MOLES

OF

“UNKNOWN”

EXAMPLE: Mass-Volume

How many liters of O

2 are needed to burn

424g of sulfur? (Assume STP conditions.)

The equation: S + O

2

SO

2

424g S X (1 mol S/32.0g S) X (1 mol O mol S) X (22.4L O

2

/1 mol O

2

2

/1

) = 297 L O

2

Note that the labels cancel.

EXAMPLE: Mass-Mass

Determine the mass of lithium hydroxide that will form in the reaction of 0.380 g lithium nitride and water by the following equation:

Li

3

N + 3H

2

O 3LiOH + NH

3

Molar Mass of Li

3

N = 3 X (6.9) + 14.0 = 34.7 g/mol

Molar Mass of LiOH = 6.9 + 16.0 + 1.0 = 23.9 g/mol

From the equation, 1 mol Li

3

N yields 3 mol LiOH.

Therefore: 0.380g Li

(3 mol LiOH/1 mol Li

= 0.78 g LiOH

3

3

N X (1 mol Li

3

N/34.7g Li

3

N) X

N) X (23.9g LiOH/1 mol LiOH)

Notice how the units cancel!

EXAMPLE: Volume-Volume

Determine the volumes of H reaction 2 H

2

S + 3 O

2

2

S and O needed to produce 14.2L of SO

2 SO

2

2

(Assume constant conditions or STP.)

2 by the

+ 2 H

2

O.

14.2L SO

2

X (2L H

2

S /2L SO

2

) = 14.2 L H

2

S

14.2L SO

2

X (3L O

2

/2L SO

2

) = 21.3 L O

2

Once more, notice how units cancel.

EXAMPLE: Other Types

Many problems may be solved using the above general steps.

Read the problem carefully to determine what is known (directly or by using molecular formulas), and then decide what factors are needed to find the unknown.

Always write the complete labels and check that everything cancels except the correct units for the unknown.

Do the math with a few keystrokes of the calculator.

Estimate your answer and compare it to the final answer. Does your answer make sense?

11-3 Limiting Reactants & Percent Yield

Consider what is needed to make a ‘box lunch’ for each student in a class of 24 for a class trip. We’ll include a sandwich, a bag of chips, an apple, a box of juice, and a Twix®. What must we buy? (List everything!)

Suppose, as we are packing the lunches, we find that one of the

“helpers” got hungry and ate a package of chips. Now how many complete ‘box lunches’ can we make?

Now, let’s further suppose that we find that three of the apples are bad!

What does this do to the number of complete lunches we may prepare?

What is limiting our ability to make 24 lunches? What will we have left?

This is the concept behind “limiting reactants” (or “limiting reagents”) in a chemical reaction. One chemical runs out first, and this prevents the reaction from going to completion

(100%). These are ‘ nonstoichiometric ’ conditions.

EXAMPLE 1: Identifying the Limiting

Reactant

The quantities of products formed in a chemical reaction are always determined by the quantity of the limiting reactant .

Solve the problem by determining the amount of product that would be formed by EACH REACTANT . (The one forming the least amount of product limits the reaction’s progress!)

Example 1: Identify the limiting reactant when 3.6 mol of Al reacts with 5.0 mol Cl

2

Balanced Equation: 2Al + 3Cl

So 3.6 mol Al X (2 mol AlCl

3

Or 5.0 mol Cl

2

X (2 mol AlCl

3 to produce AlCl

2

2AlCl

3

/3 mol Cl

2

Chlorine gives the least amount of product, AlCl limiting reactant.

3

.

/2 mol Al) = 3.6 mol AlCl

) = 3.3 mol AlCl

3

3 formed

3 formed

, and so it is the

EXAMPLE 2: Limiting Reactant

Problems

Identify the limiting reagent (reactant) when 14.5 mol P reacts with 17.0 mol O

Balanced Equation: 4P + 5O

2

2 to yield P

4

P

4

O

10

O

10

.

So 14.5 mol P X (1 mol P

4

O

10

/4 mol P) = 3.62 mol P

4

O

10

Or, 17.0 mol O

2

(1 mol P

4

O

10

/5 mol O

2

) = 3.40 mol P

4

Oxygen gives the least amount of product, and so it is the limiting reactant (limiting reagent).

O

10

EXAMPLE 3: Limiting Reactant

Problems

Identify the limiting reactant when 5.1g Li reacts with

1.5L fluorine gas (at STP) to form LiF. How many grams of LiF will result?

Balanced equation: 2Li + F

2

2LiF

For Li: 5.1g Li X (1 mol Li/6.9g Li) X (2 mol LiF/2 mol

Li) = 0.74 mol LiF

For F

F

2

: 1.5L F

2

X (1 mol F

2

/22.4L F

2

) X (2 mol LiF/1 mol

Therefore fluorine is limiting, producing only 0.13 mol of

LiF.

0.13 mol LiF X (25.9 g LiF/1 mol LiF) = 3.4 g LiF

EXAMPLE 4: Limiting Reactant

Problems

If 4.1g Cr is heated with 9.3g chlorine gas, what mass of

CrCl

3 will result?

Balanced equation: 2Cr + 3Cl

2

2CrCl

3

For Cr: 4.1g Cr X (1 mol Cr/52.0 g Cr) x (2 mol CrCl

3 mol Cr) X (158.5g CrCl

3

/1 mol CrCl

3

) = 12g CrCl

3

/2

For Cl mol Cl

2

2

: 9.3g Cl X (1 mol Cl

2

/71.0g Cl

2

3

/1 mol CrCl

) X (2 mol CrCl

3

) = 14 g CrCl

3

3

/3

Cr limits the reaction to 12 g of product, CrCl

3

.

See text page 366 – 370 for additional problems.

Why is ‘limiting reactant’ important?

Chemical reactions are run in industry every day to produce plastics, gasoline, building products, metals, electronic components, foods and hundreds of other chemicals.

To run chemical plants effectively ($$$$$) chemists and engineers try to control costs and the amounts of

‘reactants.’

Through careful studies and control of chemical reactions, they are able to maximize profits and minimize waste (pollution).

Chemists and engineers measure the efficiency of reactions by measuring “percent yield.”

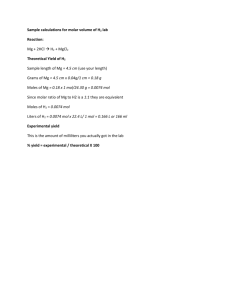

Calculating Percent Yield

A balanced chemical equation tells us the “expected” or

“theoretical” yield.

Most reactions do not ‘go to completion’ (100%) so the

“actual” yield is generally lower than expected.

Percent Yield

= (Actual Yield)/(Expected Yield) X 100%

Be sure to look at the stoichiometry of the balanced chemical reaction to calculate the expected yield!

EXAMPLE: Determine the % yield of the reaction between 3.74g of Na and excess O is formed. (84.2%)

2 if 5.34g Na

2

O

2

Did we meet the OBJECTIVES?

Define “stoichiometry” & describe its importance.

Relate stoichiometry to balanced chemical equations.

Identify & learn to solve different types of stoichiometry problems.

Determine the “limiting reactant” of a chemical reaction.

Calculate the amount of product that forms when reactants are present in proportions.

nonstoichiometric

Determine ‘percent yield’ of a chemical reaction.