Legitimacy and popular approval

advertisement

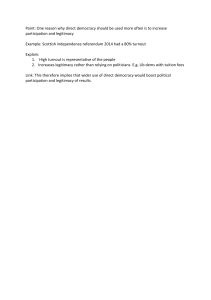

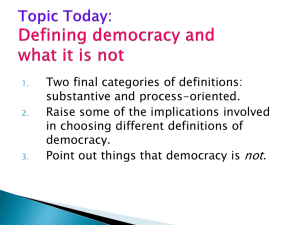

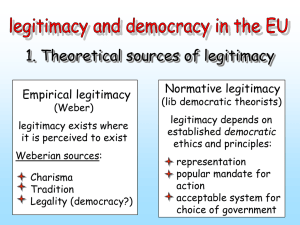

Legitimacy and popular approval: Plato’s objection Michael Lacewing enquiries@alevelphilosophy.co.uk © Michael Lacewing Legitimacy and consent: the democratic view • Individuals are free and equal. • It is wrong to force people to act in ways they have not agreed to. • The state (through the law) forces people to act in particular ways. • Therefore, the state is only legitimate if people have consented to it. Locke on social contract • Men being…by nature all free, equal and independent, no one can be put out of this estate and subjected to the political power of another without his own consent, which is done by agreeing with other men, to join and unite into a community for their comfortable, safe and peaceable living (Second Treatise § 95) Plato’s objection • Legitimacy does not depend on consent or popular approval, but ‘expertise’. • The type of freedom democracy creates is ‘licence’ – the freedom of getting what you want. • The real value of freedom – the value of choice – lies in choosing what is truly good. • But what people want is often not good. And to choose what is good, we need to know what the true good is. • Democracy is rule by ignorance, which will be bad for everyone involved. The simile of the beast • [the ruler] has no real notion of what he means by the principles or passions of which he is speaking, but calls this honourable and that dishonourable, or good or evil, or just or unjust, all in accordance with the tastes and tempers of the great brute. Good he pronounces to be that in which the beast delights and evil to be that which he dislikes. (The Republic, Book VI) The common good • Plato assumes that politics is an attempt to bring about the common good, and • that there can be knowledge about what this common good is and how to bring it about. • Therefore, special knowledge is needed to do politics. Democracy and irrationality • We don’t get the best politicians through elections: people in general are often irrational and incompetent. • The politicians we vote for are those willing to give us what we want, not what is in the common good. • The more democratic society has become, the more individualistic it is, to; until now, people care most – perhaps only – about getting the things they want for themselves. The common good again • Democracy, understood as the citizenry voting on issues of policy (directly or indirectly), is necessary to reveal what the common good is. – As long as each person is more likely to be right than wrong, a majority decision has mathematically the best chance of getting the answer right. – If there is a close connection between what people want and what the common good is, then voting helps to reveal that common good by revealing what people want. The common good again • But if all that is needed is information, then opinion polls would be better than voting • We can’t be sure a vote tells us anything about a person’s interests or desires • People are bad judges of the common good • We end up with a compromise no one wants On legitimacy again • Democracy offers protection against tyranny • ‘Free and equal’ – Equality – Autonomy – To what extent are these really promoted? • Collective identity and responsibility