Elementary, My Dear Watson: Neurons That Fire Together Stay Wired

advertisement

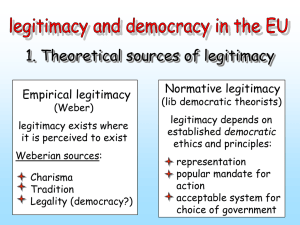

reflections from the real world Elementary, My Dear Watson: Neurons That Fire Together Stay Wired Together by Jamil Mahuad | Former President of Ecuador | jmahuad@law.harvard.edu Democracy and Politics If politics is “the method to decide who gets what and who pays the price,” there are two prices to consider: a “prize” that some people get and a “price” which some others pay. The separation between payers and beneficiaries, winners and losers is clearly connected to politics. Societies adopt a system and an accepted set of rules and practices to play this distributive game. Democracy, “the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time,” according to Winston Churchill, has proven to be the most popular way to exercise politics nowadays. Democratic rules decide the whos (who will participate and how; who will make the final call on contentious issues) and the whats (what are the stakes, the options, the rewards). Democracy appears to many as a solid, clear, precise, and self-evident concept. To others, democracy looks like a porous, fuzzy, too general, ambiguous idea that requires adjectives and qualifications to be properly grasped. What are the essential elements of democracy? What gives democracy its specificity? In Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, the president described a government “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” His dictum contains the three essential tests of democratic legitimacy: Legitimacy 1: Legitimacy of origin. The government should be “of” the people. The will of “We, the people” expressed through an open and fair electoral process decides who has the right to govern. Legitimacy 2: Legitimacy of procedures. A democratic government should be presided over “by” authorities representative of the population who enforce the rule of law. Legitimacy 3: Legitimacy of results. By leading economic growth and applying redistributive policies, governments work “for” the people. Governments should serve first and foremost the interests of the majority of the population while respecting the rights of the minorities. Many governments in developing countries have consistently failed at least one legitimacy test. Freely elected governments in Latin America in the “lost decade” of the 1980s were not able to promote economic growth and social progress. They failed the third legitimacy test. In the 1970s’ Cold War atmosphere, authoritarian regimes deposed many democratic governments arguing that to stop communism and eliminate chaos (Legitimacy 3) compensated for the lack of legitimacy of origin and method. They failed legitimacy tests 1 and 2. Some elected governments have blamed the inadequacy of institutions for their incapacity to lead development. They orchestrated autogolpes sacrificing the legitimacy of behavior at the altar of the frequently illusory legitimacy of results. The present is an excellent time for Legitimacy 3 in Latin America. Since 2003 the region’s exports have increased in volume and price due especially to the strong growth of the Chinese economy. However, Legitimacy 1 and 2 suffer in the few places where government controls the independent media. This article reflects on the building up of Legitimacy 1. Neuroscience, by explaining human decision making, contributes to clarify how voters decide which authorities and rules would come “of” the people. Neuroscience and Decision Making Two famous political expressions attempt to prescribe political practices: Nazi propagandist Goebbels said, “Repeat a lie one thousand times and it becomes the truth”; Machiavelli wrote, “To govern is to make believe.” What does neuroscience have to say about these statements? Neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield, considered the “greatest living Canadian” in the 1960s, demonstrated that our brain collects and retrieves memories by bundling together events and their associated feelings, storing them in a physically accessible part of our brain, and constructing a neural pathway to reach them. If a certain stimulus triggers the playback key, we not only remember but involuntarily relive the stored experience with its original intensity. We can discover the impulse that evokes the positive or negative stored memory. In 1964, while working for President Lyndon B. Johnson’s presidential campaign, Tony Schwartz applied the same basic understanding of the human brain’s activity to generate his insightful Resonance Theory of Communication and tested it in practice with the “Daisy ad,” poised to become the most famous TV ad in political history. Campaigns are not the right moment to educate the audience, to give them new information to process, Schwartz thought. How a voter feels about a candidate determines how she votes. Any communication activates unconscious brain networks; effective communication triggers 3 lasaforum fall 2013 : volume xliv : issue 4 the “right” one to elicit the expected emotional response. Voting is not a rational decision-making process; it is rather a highly emotional one. When accused of manipulating people, Schwartz argued that the messenger could not do anything without the receiver’s cooperation. In the worst case, he said, he would be accused of “partipulating” because he offers the stimulus and the other provides the reaction. Communication is a collaborative effort. Electoral campaigns will never be the same after Schwartz’s theory. Marshall McLuhan called him the “guru of electronic media.” Professor Gary Orren has been teaching the very popular course “Persuasion: the Science and Art of Effective Influence” for decades at the Harvard Kennedy School. The golden rule of persuasion is to know your audience, he says. Whom are you speaking to? They would be persuaded if they perceive that your message is salient (relevant to their lives), simple (easy to understand and remember), and sound (appealing to their rationality). George Lakoff shocked our political minds by defending the idea that we think inside frames coming from the “metaphors we live by.” The mind is in the brain, he believes. As we can’t rationally control our neural system, most of our reasoning is unconscious, hence emotional. Daniel Kahneman, the first psychologist to win the Nobel Prize in economics (2002), in his best seller Thinking, Fast and Slow explains that humans have two systems of thinking. System 1 is automatic, fast, hyperactive, nonrational, and cannot be deactivated at will; System 2 is slow, lazy, fact-based, and needs to be voluntarily engaged. 4 We spend most of our time in our emotional self, in System 1 (basically impressions and desires). System 2 follows system 1 (we believe our impressions and act on our desires) contextualizing them with explicit beliefs and deliberate choices. Reflecting on the well-known “Invisible Gorilla Experiment,” Kahneman highlights how intensely focusing on an imposed task (counting ball passes and ignoring one of the teams) can make people effectively blind. “We can be blind to the obvious…be blind to our blindness.” No one who watches the video without knowing the task would miss the gorilla in the scene. Airwaves Are to Elections What Airpower Is to War Political consultants know that the act of voting is the corollary of a three-step process. The electoral campaign’s purpose is not to change the voter’s intention (final result) but to influence every instance of the voter’s decision making by working on the stimulus/associations network. Campaign communication strategies develop three objectives in sequence: Step 1: Get name recognition. A person needs to “exist,” to get into the “political menu,” to be in the top of the mind recollection of the voter to become a viable candidate. Getting a recognizable name takes a lot of time and/or money. Competition is fierce. Newspapers, radio, and TV screens are already cluttered with familiar names and faces. Incumbents have the upper hand in Step 1. Step 2: Win the favorability contest. Candidates evoke strong emotional reactions. That is why it is not possible to wrap them up nicely to “sell” them like emotionally inert industrial products. The favorable/unfavorable ratio opens the space for increasing vote intention or limits it with a low ceiling cap. Step 3: Harden the favorability ratio. Investigate the reasons for the emotional reaction expressed in Step 2. Unveil the trigger and the emotional/belief bundle associated with it. Discover what aspects of the candidate’s appearance, positions, or actions make the click. After understanding why voters like or dislike a candidate it is possible to measure the depth of their emotional reaction and figure out how to deactivate that circuit or create and activate an alternative one. “Hard” voters—either for or against—are very difficult if not impossible to change due to their strong allegiance. They enter into their familiar stimulus/recollection groove and remain there. “Soft” voters, in contrast, can be influenced by the spreading of “information”—false or true—about any candidate. Negative campaigns create or reinforce negative associations. They work at Step 3 in order to change Step 2, the favorable/ unfavorable ratio. The decision to vote for or against a candidate is the logical consequence of this process: if I know somebody (Step 1), have a favorable opinion about him/her (Step 2) based on solid reasons (Step 3), I will vote for him/her. This process is public. In a mass society, it needs to be implemented through the mass media, the only mechanism to get to the eyes and ears of all voters. Voters have the right to access different perspectives on reality and evaluate them before making their choices. The legitimacy of origin is based on debate. Political debate clarifies concepts, exposes risks, analyzes options and compares alternatives. It is democracy at work. We lose this practice when economic or political powers control access to media. The control or monopoly of mass media plus the relentless repetition of a “unique selling proposition” is a poisonous combination for democracy. It substitutes propaganda in place of information. Later propaganda becomes ideology, the only valid truth that deserves to be disseminated. Unfortunately, a few Latin American governments enthusiastically embrace the Orwellian Ministry of Truth concept. They suppress or capture independent media through blatant abuse of power, manipulation of judges, or economic asphyxia. The government-controlled media exclusively broadcast government propaganda; they saturate air and print spaces with ideology disguised as information. They cancel debates, eliminate discussion, disqualify, threaten, and ostracize opponents. Where is Legitimacy 1 in that atmosphere? If we don’t understand the emotional mechanisms of human decision making, we will not realize how a totalitarian-inspired but research-based, strategically planned, artistically designed, massively broadcasted campaign inundates the voter’s System 1 and practically eliminates consideration of other options. Such a campaign destroys the essence of democracy while playing within apparently democratic rules. organized lines in front of the voting booths. References The democratic spirit is resilient, however. Lawyers and computer programmers frequently remind us that we undo actions in the same way that we do them. To restore a democratic lifestyle we need to eliminate absolute truths and reopen the capacity to doubt, reframe, and disseminate antagonistic perspectives. We need to generate a critical mass, a choir of discordant voices, and guarantee them access to mass media. Redundancy here is not a vice but a virtue. 2011 Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. In summary, words, facial expressions, and body language activate neural circuits. The most-used brain circuits (neurons that fire together) become the default “thinking” (neurons stay wired together). We can easily mix illusion and reality through consistent repetition controlled by mass media that “nails” as a truth a bundle of carefully intertwined threads of emotional stimuli. 2003 Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Kahneman, Daniel Lakoff, George 2004 Don’t Think of an Elephant! Know Your Values and Frame the Debate: The Essential Guide for Progressives. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing. 2008 The Political Mind: Why You Can’t Understand 21st-Century Politics with an 18th-Century Brain. New York: Viking. Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson Schwartz, Tony 1974 The Responsive Chord. New York: Doubleday. 1983 Media, the Second God. New York: Doubleday. Beware of those that apply Goebbels’s “Repeat a lie one thousand times” aiming to achieve Machiavelli’s “To govern is to make believe” and cynically claim democratic titles. They are using democracy to destroy Democracy. If we are not aware of the modern mechanisms of persuasion we can naively support these totalitarian attitudes by, for example, certifying elections as clean and fair based on formal administrative procedures or election-day conduct like 5