Managing the Investment Portfolio

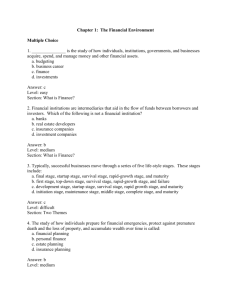

advertisement

Bank Management, 6th edition. Timothy W. Koch and S. Scott MacDonald Copyright © 2006 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning Managing the Investment Portfolio Chapter 13 William Chittenden edited and updated the PowerPoint slides for this edition. The Investment Portfolio Most banks concentrate their asset management efforts on loans Managing investment securities is typically a secondary role, especially at smaller banks Historically, small banks have purchased securities and held them to maturity The Investment Portfolio Large banks, in contrast, not only buy securities for their own portfolios, but they also: Manage a securities trading account Manage an underwriting subsidiary that helps municipalities issue debt in the money and capital markets The Investment Portfolio Historically, bank regulators have limited the risk associated with banks owning securities by generally: Prohibiting banks from purchasing common stock (for income purposes) Limiting debt instruments to investment grade securities Increasingly, banks are pursuing active strategies in managing investments in the search for higher yields Dealer Operations and the Securities Trading Account When banks purchase securities, they must indicate the underlying objective for accounting purposes: Held-to-Maturity Trading Available-for-Sale Dealer Operations and the Securities Trading Account Held to Maturity Securities purchased with the intent and ability to hold to final maturity Carried at historical (amortized) cost on the balance sheet Unrealized gains and losses have no impact on the income statement Dealer Operations and the Securities Trading Account Trading: Securities purchased with the intent to sell them in the near term Carried at market value on the balance sheet with unrealized gains and losses included in income Dealer Operations and the Securities Trading Account Available for Sale: Securities that are not classified as either held-to-maturity securities or trading securities Carried at market value on the balance sheet with unrealized gains and losses included as a component of stockholders’ equity Dealer Operations and the Securities Trading Account Banks perform three basic functions within their trading activities: Offer investment advice and assistance to customers managing their own portfolios Maintain an inventory of securities for possible sale to investors Their willingness to buy and sell securities is called making a market Traders speculate on short-term interest rate movements by taking positions in various securities Dealer Operations and the Securities Trading Account Banks earn profits from their trading activities in several ways: When making a market, they price securities at an expected positive spread Bid Price the dealer is willing to pay Ask Price the dealer is willing to sell Traders can also earn profits if they correctly anticipate interest rate movements Objectives of the Investment Portfolio A bank’s investment portfolio differs markedly from a trading account Objectives of the Investment Portfolio Safety or preservation of capital Liquidity Yield Credit risk diversification Help in manage interest rate risk exposure Assist in meeting pledging requirements Objectives of the Investment Portfolio Accounting for Investment Securities FASB 115 requires security holdings to be divided into three categories Held-to-Maturity (HTM) Trading Available-for-Sale The distinction between investment motives is important because of the accounting treatment of each Objectives of the Investment Portfolio Accounting for Investment Securities A change in interest rates can dramatically affect the market value of a security The difference between market value and the purchase price equals the unrealized gain or loss on the security; assuming a purchase at par: Unrealized Gain/Loss = Market Value – Par Value Objectives of the Investment Portfolio Accounting for Investment Securities Assume interest rates increase and bond prices fall: Held-to-Maturity Securities There is no impact on either the balance sheet or income statement Trading Securities The decline in value is reported as a loss on the income statement Available-for-Sale Securities The decline in value reduces the value of bank capital Objectives of the Investment Portfolio Safety or Preservation of Capital A primary objective of the investment portfolio is to preserve capital by purchasing securities when there is only a small risk of principal loss. Regulators encourage this policy by requiring that banks concentrate their holdings in investment grade securities, those rated Baa (BBB) or higher. Objectives of the Investment Portfolio Liquidity Commercial banks purchase debt securities to help meet liquidity requirements Securities with maturities under one year can be readily sold for cash near par value and are classified as liquid investments In reality, most securities selling at a premium can also be quickly converted to cash, regardless of maturity, because management is willing to sell them Investment Portfolio for a Hypothetical Commercial Bank Liquidity Purchase Date Current Date: September 30, 2005 Annual Book Coupon Value Description Income 12/15/95 $4,000,000 10/15/95 2,000,000 6/6/99 500,000 10/l/94 1,000,000 $4,000,000 par value U.S. Treasury note at 11%, due 11/15/08 $2,000,000 par value Federal National Mortgage Association bonds at 8.75%, due 10/15/10 $500,000 par value Allegheny County, PA, Arated general obligations at 5.15%, due 3/l/11 $1,000,000 par value State of Illinois Aaa-rated general obligations at 11%, due 10/1/19 Market Value $440,000 $4,099,000 175,000 1,824,000 25,750 482,500 110,000 1,190,000 Objectives of the Investment Portfolio Yield To be attractive, investment securities must pay a reasonable return for the risks assumed The return may come in the form of price appreciation, periodic coupon interest, and interest-on-interest The return may be fully taxable or exempt from taxes Objectives of the Investment Portfolio Diversify Credit Risk The diversification objective is closely linked to the safety objective and difficulties that banks have with diversifying their loan portfolios Too often loans are concentrated in one industry that reflects the specific economic conditions of the region Investment portfolios give banks the opportunity to spread credit risk outside their geographic region and across different industries Objectives of the Investment Portfolio Help Manage Interest Rate Exposure Investment securities are very flexible instruments for managing a bank’s overall interest rate risk exposure Banks can select terms that meet their specific needs without fear of antagonizing the borrower They can readily sell the security if their needs change Objectives of the Investment Portfolio Pledging Requirements By law, commercial banks must pledge collateral against certain types of liabilities. Banks that borrow via repurchase agreements essentially pledge part of their government securities portfolio against this debt Public deposits Borrowing from the Federal Reserve Borrowing from FHLBs Composition of the Investment Portfolio Money market instruments with short maturities and durations include: Treasury bills Large negotiable CDs Bankers acceptances Commercial paper Repurchase agreements Tax anticipation notes. Composition of the Investment Portfolio Capital market instruments with longer maturities and duration include: Long-term U.S. Treasury securities Obligations of U.S. government agencies Obligations of state and local governments and their political subdivisions labeled municipals Mortgage-backed securities backed both by government and private guarantees Corporate bonds Foreign bonds Composition of the Investment Portfolio A. All Banks Over Time Percentage of Total Assets 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 Billions of dollars 1970 U.S. Treasury securities Agency securities Municipal securities Corporate & foreign securities Total Total financial assets (billions of $) 12.1% 9.8% 7.8% 8.3% 5.4% 6.2% 2.9% 1.3% 2.7 3.9 4.1 3.2 8.4 10.4 11.2 12.9 13.6 11.6 10.0 9.7 3.5 2.1 1.8 1.7 0.6 0.9 0.5 1.0 2.7 2.5 4.1 6.6 29.0% 26.2% 22.4% 22.2% 20.0% 21.2% 20.0% 22.5% $517 $886 $1,482 $2,375 $3,334 $4,488 $6,469 $8,487 B. 2000 Percentage of Total Consolidated Assets, December 31, 2000 Commercial Banks Ranked by Assets 10 11-100 101-1,000 >1,000 Largest Largest Largest Largest Investment securities U.S. Treasury securities 0.80% 1.00% 1.00% 0.90% U.S. Gov't. agency & corporate securities 9.20% 13.00% 17.00% 16.20% Private mortgage-backed securities 1.10% 2.10% 0.90% 0.20% Municipal securities 0.60% 1.00% 3.00% 4.70% Other securities 3.40% 2.90% 2.00% 1.10% Equities 0.20% 0.20% 0.40% 0.30% Total investment securities 15.30% 20.20% 24.30% 23.40% Trading account securities 5.90% 1.10% 0.10% 0.00% Total 21.20% 21.30% 24.40% 23.40% 2004 Characteristics of Taxable Securities Money Market Investments Highly liquid instruments which mature within one year that are issued by governments and large corporations Very low risk as they are issued by wellknown borrowers and a active secondary market exists Banks purchase money market instruments in order to meet liquidity and pledging requirements and earn a reasonable return Characteristics of Taxable Securities Capital Market Investments Consists of instruments with original maturities greater than one year Banks are restricted to “investment grade” securities, those rated Baa (BBB) or above; i.e., no junk bonds If banks purchase non-rated securities, they must perform a credit analysis to validate that they are of sufficient quality relative to the promised yield . Money Market Investments Repurchase Agreements (Repos) A loan between two parties, with one typically either a securities dealer or commercial bank The lender or investor buys securities from the borrower and simultaneously agrees to sell the securities back at a later date at an agreed-upon price plus interest Essentially are collateralized federal funds transactions Money Market Investments Repurchase Agreements (Repos) The minimum denomination is generally $1 million, with maturities ranging from one day to one year The rate on one-day repos is referred to as the overnight repo rate and is quoted on an add-on basis assuming a 360-day year $ Interest = Par Value x Repo Rate x Days/360 Longer-term transactions are referred to as term repos and the associated rate the term repo rate Money Market Investments Treasury Bills Marketable obligations of the U.S. Treasury that carry original maturities of one year or less They exist only in book-entry form, with the investor simply holding a dated receipt Investors can purchase bills in denominations as small as $1,000, but most transactions involve much larger amounts Money Market Investments Treasury Bills Each week the Treasury auctions bills with 13-week and 26-week maturities Investors submit either competitive or noncompetitive bids With a competitive bid, the purchaser indicates the maturity amount of bills desired and the discount price offered Non-competitive bidders indicate only how much they want to acquire Money Market Investments Treasury Bills Treasury bills are purchased on a discount basis, so the investor’s income equals price appreciation The Treasury bill discount rate is quoted in terms of a 360-day year: FV P 360 DR FV N Where DR = Discount Rate FV = Face Value P = Purchase Price N = Number of Days to Maturity Money Market Investments Treasury Bills Example: A bank purchases $1 million in face value of 26-week (182-day) bills at $990,390. What is the discount rate and effective yield? The discount rate is: $1,000,000 $990,390 360 DR 1.90% $1,000,000 182 The true (effective) yield is: $1,000,000 $990,390 Effective Yield 1 $990,390 (365/182) 1 1.956% Money Market Investments Certificates of Deposit Dollar-denominated deposits issued by U.S. banks in the United States Fixed maturities ranging from 7 days to several years Pay yields above Treasury bills. Interest is quoted on an add-on basis, assuming a 360-day year Money Market Investments Eurodollars Dollar-denominated deposits issued by foreign branches of banks outside the United States The Eurodollar market is less regulated than the domestic market, so the perceived riskiness is greater. Money Market Investments Commercial Paper Unsecured promissory notes issued by corporations Proceeds are use to finance short-term working capital needs The issuers are typically the highest quality firms Minimum denomination is $10,000 Maturities range from 3 to 270 days Interest rates are fixed and quoted on a discount basis Small banks purchase large amounts of commercial paper as investments Money Market Investments Bankers Acceptances A draft drawn on a bank by firms that typically are importer or exporters of goods Has a fixed maturity, typically up to nine months Priced as a discount instrument like Tbills Capital Market Investments Treasury Notes and Bonds Notes have a maturity of 1 - 10 years Bonds have a maturity greater than 10 years Most pay semi-annual coupons Some are zeros or STRIPS Sold via closed auctions Rates are quoted on a coupon-bearing basis with prices expressed in thirtyseconds of a point, $31.25 per $1,000 face value Capital Market Investments Treasury STRIPS Many banks purchase zero-coupon Treasury securities as part of their interest rate risk management strategies The U.S. Treasury allows any Treasury with an original maturity of at least 10 years to be “stripped” into its component interest and principal pieces and traded via the Federal Reserve wire transfer system. Each component interest or principal payment constitutes a separate zero coupon security and can be traded separately from the other payments Capital Market Investments Treasury STRIPS Example Consider a 10-year, $1 million par value Treasury bond that pays 9 percent coupon interest semiannually ($45,000 every six months) This security can be stripped into 20 separate interest payments of $45,000 each and a single $1 million principal payment, or 21 separate zero coupon securities. Capital Market Investments U.S. Government Agency Securities Composed of two groups Members who are formally part of the federal government Federal Housing Administration Export-Import Bank Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae) Capital Market Investments U.S. Government Agency Securities Composed of two groups Members who are government-sponsored agencies Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) Student Loan Marketing Association (Sallie Mae) Default risk is low even though these securities are not direct obligations of the Treasury; most investors believe there is a moral obligation. These issues normally carry a risk premium of about 10 to 100 basis points. Federal Status of U.S. Government Agency Securities Agency Full Faith and Credit of the U.S. Authority to Borrow from the Federal Government Treasury Interest on Bonds Generally Exempt from State and Local Taxes Farm Credit System Farm Credit System Financial Assistance Corporation (FCSFAC) No Yes—$260 million revolving line of credit. Yes Yes Yes Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLB) No Yes—FCSFAC began issuing bonds in late 1988. Yes—the Treasury is authorized to purchase up to $4 billion of FHLB securities. Yes—indirect line of credit through the FHLBs. No Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac)* Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA) (Fannie Mae)* Financing Corporation (FICO) Student Loan Marketing Association (Sallie Mae) United States Postal Service† Resolution Funding Corporation (RefCorp) Farmers Home Administration†(FmHA) No No No Not since 1/9/82 Guarantee may be extended if Postal Service requests and Treasury determines this to be in the public interest. No Yes Yes—at FNMA request the Treasury may purchase $2.25 billion of FNMA securities. No Yes—at its discretion the Treasury may purchase $1 billion of Sallie Mae obligations. Yes—the Postal Service may require the Treasury to purchase up to $2 billion of its obligations. Federal Financing Bank (FFB) Yes General Services Administration†(GSA) Government National Mortgage Association†(GNMA) Maritime Administration Guaranteed Ship Financing Bonds issued after 1972 Small Business Administration (SBA) Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) Bonds Yes No No Yes—FFB can require the Treasury to purchase up to $5 billion of its obligations. The Treasury Secretary is authorized to purchase any amount of FFB obligations at his or her discretion. No Yes No Yes Yes No No No Yes—up to $150 million. Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No No Yes Yes No No, with exceptions Yes No, except for states involved in the interstate compact Capital Market Investments Callable Agency Bonds Securities issued by governmentsponsored enterprises in which the issuer has the option to call the bonds prior to final maturity Typically, there is a call deferment period during which the bonds cannot be called The issuer offers a higher promised yield relative to comparable non-callable bonds The present value of this rate differential essentially represents the call premium Capital Market Investments Callable Agency Bonds Banks find these securities attractive because they initially pay a higher yield than otherwise similar non-callable bonds The premium reflects call risk If rates fall sufficiently, the issuer will redeem the bonds early, refinancing at lower rates, and the investor gets the principal back early which must then be invested at lower yields for the same risk profile Capital Market Investments Conventional Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBSs) Any security that evidences an undivided interest in the ownership of mortgage loans The most common form of MBS is the pass-through security Even though many MBSs have very low default risk, they exhibit unique interest rate risk due to prepayment risk As rates fall, individuals will refinance Capital Market Investments GNMA Pass-Through Securities Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae) Government entity that buys mortgages for low income housing and guarantees mortgage-backed securities issued by private lenders Structure of the GNMA Mortgage-Backed Pass-Through Security Issuance Process Capital Market Investments FHLMC Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) FNMA securities Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) Both are: Private corporations Operate with an implicit federal guarantee Buy mortgages financed largely by mortgagebacked securities Capital Market Investments Privately Issued Pass-Through Issued by banks and thrifts, with private insurance rather than government guarantee Prepayment Risk on Mortgage-Backed Securities Borrowers may prepay the outstanding mortgage principal at any point in time for any reason Prepayments generally occur because of fundamental demographic trends as well as movements in interest rates Prepayments typically increase as interest rates fall and slow as rates increase Forecasting prepayments is not an exact science Prepayment Risk on Mortgage-Backed Securities Example: Current mortgage rates are 8% and you buy a MBS paying 8.25% Because rates have fallen, you paid a premium to earn the higher rate With rates only .25% lower, it is unlikely individuals will refinance If rates fall 3%, there will be a large increase in prepayments due to refinancing If the prepayments are fast enough, you may never recover the premium you paid The value of the MBS if the pre-payment rate varies from 6% B. The Effect of Relative Coupon on the Prepayment Rate C. The Effect of Mortgage Age on the Prepayment Rate 3 Pre-payment experience is low on new mortgages, increases through five years then declines. 2 1 0 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 Relative Coupon Rate (Percent) 1.25 Percent per Month Prepayment risk on mortgage-backed securities Percent per Month Measures the value of the MBS if the prepayment rate remains at 6% regardless of the level of mortgage rates. Pre-payment rates increase sharply when mortgage rates fall 1.00 .75 .50 .25 0 1 5 10 15 20 25 Mortgage Age (Years) Unconventional Mortgage-Backed Securities Collateralized Mortgage Obligations (CMOs) Security backed by a pool of mortgages and structured to fall within an estimated maturity range (tranche) based on the timing of allocated interest and principal payments on the underlying mortgages Tranche: The principal amount related to a specific class of stated maturities on a collateralized mortgage obligation. The first class of bonds has the shortest maturities Unconventional Mortgage-Backed Securities Collateralized Mortgage Obligations (CMOs) CMOs were introduced to circumvent some of the prepayment risk associated with the traditional pass-through security CMOs are essentially bonds An originator combines various mortgage pools to serve as collateral and creates classes of bonds with different maturities Unconventional Mortgage-Backed Securities Collateralized Mortgage Obligations (CMOs) The first class, or tranche, has the shortest maturity Interest payments are paid to all classes of bonds but principal payments are paid to the first tranche until they have been paid off After the first tranche is paid, principal payments are made to the second tranche, etc Unconventional Mortgage-Backed Securities Types of CMOs Planned Amortization Class CMO (PAC) A security that is retired according to a planned amortization schedule, while payments to other classes of securities are slowed or accelerated Least risky of the CMOs Objective is to ensure that PACs exhibit highly predictable maturities and cash flows Z-Tranche Final class of securities in a CMO, exhibiting the longest maturity and greatest price volatility These securities often accrue interest until all other classes are retired Unconventional Mortgage-Backed Securities CMOs’ Advantages over MBS Pass- Throughs Some classes (tranches) exhibit less prepayment risk; some exhibit greater prepayment risk Appeal to investors with different maturity preferences by segmenting the securities into maturity classes Unconventional Mortgage-Backed Securities Stripped Mortgage-Backed Securities More complicated in terms of structure and pricing characteristics Example: Consider a 30 year, 12% fixed-rate mortgage There will be 30 x 12 (360) payments (principal plus interest Loan amortization means the principal only payments are smaller in the beginning: P1 < P2 < … < P360 Interest only payments decrease over time: I1 > I2 > … > I360 Features of Pass-Through, Government, and Corporate Securities Pass-Throughs Credit risk Liquidity Range of coupons (discount to premium) Range of maturities Treasuries Generally high grade; range from High grade to government guaranteed to A Government guaranteed. speculative. (private pass- throughs). Good for agency issued/guaranteed Excellent. Generally limited. pass-through. Full range. Full range. Medium and long term (fast-paying and seasoned pools can provide Full range. shorter maturities than stated). Complex prepayment pattern; can limit through selection Noncallable (except Call protection investor variables, such as coupon seasoning, certain 30-year bonds). and program. Frequency of payment Corporates Monthly payments of principal and Semiannual interest interest. payment. Stripped Treasuries Backed by government securities. Fair. Full range for a few Zero coupons (discount issuers. securities). Full range. Full range. Generally callable after initial limited Noncallable. period of 5 to 10 years. Semiannual interest (except Eurobonds, No payments until which pay interest maturity. annually). Lower than for bonds of comparable Estimate only for small Minimum average maturity; can only be estimated due number of callable life known, otherwise Known with certainty. Average life issues; otherwise, known to prepayment risk. a function of call risk. with certainty. of prepayment risk; can Unless callable, a simple Function of call risk; Known with certainty; Duration/intere Function only be estimated; can be negative function of yield, coupon, can be negative when no interest rate risk if st rate risk and maturity; is known call risk is high. when prepayment risk is high. held to maturity. with certainty. Cash flow yield based on monthly Based on semiBond equivalent yield Based on semiannual prepayments and constant CPR annual coupon Basis for yield assumption (usually most recent coupon payments and payments and 360- based on either 360- or quotes three- month historical prepayment 365-day year. day year of twelve 30- 365-day year depending on sponsor. experience). day months. Settlement Once a month. Any business day. Any business day. Any business day. Asset-Backed Securities Conceptually, an asset-backed security is comparable to a mortgage-backed security in structure The securities are effectively “passthroughs” since principal and interest are secured by the payments on the specific loans pledged as security Two popular asset-backed securities are: Collateralized automobile receivables (CARS) CARDS Securities backed by credit card loans to individuals Other Investments Corporate and Foreign Bonds At the end of 2004, banks held $560 billion in corporate and foreign bonds Mutual Funds Banks have increased their holdings in mutual funds to over $25 billion in 2004 Mutual fund investments must be marked-to-market and can cause volatility on the values reported on the bank’s balance sheet Characteristics of Municipal Securities Municipals are exempt from federal income taxes and generally exempt from state or local as well General obligation Principal and interest payments are backed by the full faith, credit, and taxing authority of the issuer Revenue Bonds Backed by revenues generated from the project the bond proceeds are used to finance Industrial Development Bonds Expenditures of private corporations Summary of Terms for a Municipal School Bond Due Date Amount Coupon Yield Sequoia Union High School District $30,000,000 General Obligation Bonds Election of 2001 Dated: May 1, 2002 Due: July 1, 2003 through July 1, 2031 Callable: July 1, 2011 at 102.0% of par, declining to par as of July 1, 2013 Winning Bid: Salomon Smith Barney, at 100.0000, True interest cost (TIC) of 5.0189% Other Managers: Bear, Stearns & Co., Inc., CIBC World Markets Corp., 7/1/2003 7/1/2004 7/1/2005 7/1/2006 7/1/2007 7/1/2008 7/1/2009 7/1/2010 7/1/2011 7/1/2012 7/1/2013 7/1/2014 7/1/2015 7/1/2016 7/1/2017 7/1/2018 7/1/2019 7/1/2020 7/1/2021 7/1/2022 7/1/2023 7/1/2024 7/1/2025 7/1/2026 $225,000 $520,000 $545,000 $575,000 $605,000 $635,000 $665,000 $700,000 $735,000 $765,000 $800,000 $835,000 $870,000 $910,000 $950,000 $995,000 $1,045,000 $1,095,000 $1,150,000 $1,210,000 $1,270,000 $1,335,000 $1,405,000 $1,480,000 7/1/2031 $8,650,000 7.00% 7.00% 7.00% 7.00% 7.00% 7.00% 7.00% 4.00% 4.00% 4.13% 4.25% 4.38% 4.50% 4.60% 4.70% 4.80% 4.90% 5.00% 5.00% 5.00% 5.00% 5.00% 5.00% 5.00% 2.00% 2.50% 3.00% 3.25% 3.50% 3.70% 3.80% 3.90% 4.00% 4.13% 4.25% 4.38% 4.50% 4.60% 4.70% 4.80% 4.90% 5.00% 5.00% 5.00% 5.00% 5.00% 5.20% 5.21% 5.13% 5.21% Characteristics of Municipal Securities Money Market Municipals Municipal notes provide operating funds for government units Banks buy large amounts of short-term municipals They often work closely with municipalities in placing these securities Capital Market Municipals Includes general obligation bonds and revenue bonds Characteristics of Municipal Securities Credit Risk in the Municipal Portfolio Until the 1970s, few municipal securities went into default Deteriorating conditions in many large cities ultimately resulted in defaults by: New York City (1975), Cleveland (1978), Washington Public Power & Supply System (WHOOPS) (1983) Characteristics of Municipal Securities Liquidity Risk Municipals exhibit substantially lower liquidity than Treasury or agency securities The secondary market for municipals is fundamentally an over-the-counter market Small, non-rated issues trade infrequently and at relatively large bid-ask dealer spreads Large issues of nationally known municipalities, state agencies, and states trade more actively at smaller spreads Characteristics of Municipal Securities Liquidity Risk Name recognition is critical, as investors are more comfortable when they can identify the issuer with a specific location Insurance also helps by improving the rating and by association with a known property and casualty insurer Characteristics of Municipal Securities Municipals are less volatile in price than Treasury securities This is generally attributed to the peculiar tax features of municipals The municipal market is segmented On the supply side, municipalities cannot shift between short- and long-term securities to take advantage of yield differences because of constitutional restrictions on balanced operating budgets Thus long-term bonds cannot be substituted for shortterm municipals to finance operating expenses, and Capital expenditures are not financed by ST securities Characteristics of Municipal Securities Municipals are less volatile in price than Treasury securities The municipal market is segmented. On the demand side, banks once dominated the market for short-term municipals Today, individuals via tax-exempt money market mutual funds dominate the short maturity spectrum Establishing Investment Policy Guidelines Each bank’s asset and liability or risk management committee is responsible for establishing investment policy guidelines These guidelines define the parameters within which investment decisions help meet overall return and risk objectives Because securities are impersonal loans that are easily bought and sold, they can be used at the margin to help achieve a bank’s liquidity, credit risk, and earnings sensitivity or duration gap targets Establishing Investment Policy Guidelines Investment guidelines identify specific goals and constraints regarding: Return Objective Composition of Investments Liquidity Considerations Credit Risk Considerations Interest Rate Risk Considerations Total Return Versus Current Income Active Investment Strategies Portfolio managers can buy or sell securities to achieve aggregate risk and return objectives Investment strategies can subsequently play an integral role in meeting overall asset and liability management goals Unfortunately, not all banks view their securities portfolio in light of these opportunities Active Investment Strategies Many smaller banks passively manage their portfolios using simple buy and hold strategies The purported advantages are that such a policy requires limited investment expertise and virtually no management time; lowers transaction costs; and provides for predictable liquidity Active Investment Strategies Other banks actively manage their portfolios by: Adjusting maturities Changing the composition of taxable versus tax-exempt securities Swapping securities to meet risk and return objectives Advantage is that active portfolio managers can earn above-average returns by capturing pricing discrepancies in the marketplace Disadvantages are: that managers must consistently out predict the market for the strategies to be successful, and high transactions costs The Maturity or Duration Choice for LongTerm Securities The optimal maturity or duration is possibly the most difficult choice facing portfolio managers It is very difficult to outperform the market when forecasting interest rates Some managers justify passive buy and hold strategies because of a lack of time and expertise Other managers actively trade securities in an attempt to earn above average returns Passive Maturity Strategies Laddered (or Staggered) maturity strategy Management initially specifies a maximum acceptable maturity and securities are evenly spaced throughout maturity Securities are held until maturity to earn the fixed returns Passive Maturity Strategies Barbell Maturity Strategy Differentiates investments between those purchased for liquidity and those for income Short-term securities are held for liquidity Long-term securities for income Also labeled the long and short strategy Active Maturity Strategies Active portfolio management involves taking risks to improve total returns by: Adjusting maturities Swapping securities Periodically liquidating discount instruments To be successful, the bank must avoid the trap of aggressively buying fixedincome securities at relatively low rates when loan demand is low and deposits are high Active Maturity Strategies Riding the Yield Curve This strategy works best when the yield curve is upward-sloping and rates are stable. Three basic steps: Identify the appropriate investment horizon Buy a par value security with a maturity longer than the investment horizon and where the coupon yield is higher in relationship to the overall yield curve Sell the security at the end of the holding period when time remains before maturity Riding the Yield Curve Example Initial conditions and assumptions: • 5-year investment Period: horizon Year-End • yield curve is upward-sloping, 1 2 • 5-year securities 3 yielding 7.6 % and 4 • 10-year securities 5 yielding 8 %. Total • Annual coupon 5 interest is reinvested at 7%. Buy a 5-Year Security Coupon Interest Buy a 10-Year Security and Sell It after 5 Years Reinvestment Coupon Reinvestment Income at Interest Income at 7% 7% $7,600 $ 8,000 7,600 $ 532 8,000 $ 560 7,600 1,101 8,000 1,159 7,600 1,710 8,000 1,800 7,600 2,362 8,000 2,486 $38,000 $5,705 $40,000 $6,005 Principal at Maturity = $100,000 Price at Sale after 5 years = $101,615 when rate = 7.6% Expected Total Return Calculation 100,000 38,000 5,705 i5yr 100,000 0.0752 1/5 1 y10yr 1/5 101,615 40,000 6,005 1 0.0810 100,000 Interest Rates and the Business Cycle Expansion Increasing Consumer Spending Inventory Accumulation Rising Loan Demand Federal Reserve Begins to Slow Money Growth Peak Monetary Restraint High Loan Demand Little Liquidity Interest Rates and the Business Cycle Contraction Falling Consumer Spending Inventory Contraction Falling Loan Demand Federal Reserve Accelerates Money Growth Trough Monetary Policy Eases Limited Loan Demand Excess Liquidity Interest rates and the Business Cycle Interest Rates (Percent) Peak Short-Term R ates Long-Term Rates Contraction Expansion Expansion Trough Time The inverted U.S. yield curve has predicted these recessions: Date when 1yr > 10 yr rate April 1968 March 1973 September 1978 September 1980 February 1989 December 2000* Time until next recession 20 months (Dec. 1969) 8 months (Nov 1973) 16 months (Jan. 1980) 10 months (July 1981) 17 months (July 1990) 3 months (March 2001) 12.3 months average Passive Strategies Over the Business Cycle One popular passive investment strategy follows from the traditional belief that a bank’s securities portfolio should consist of primary reserves and secondary reserves This view suggests that banks hold shortterm, highly marketable securities primarily to meet unanticipated loan demand and deposit withdrawals Once these primary liquidity reserves are established, banks invest any residual funds in long-term securities that are less liquid but offer higher yields Passive Strategies Over the Business Cycle A problem arises because banks normally have excess liquidity during contractionary periods when loan demand is declining and the Fed starts to pump reserves into the banking system Interest rates are thus relatively low. Passive Strategies Over the Business Cycle Banks employing this strategy add to their secondary reserve by buying longterm securities near the low point in the interest rate cycle Long-term rates are typically above short-term rates, but all rates are relatively low With a buy and hold orientation, these banks lock themselves into securities that depreciate in value as interest rates move higher Active Strategies Over the Business Cycle Many portfolio managers attempt to time major movements in the level of interest rates relative to the business cycle and adjust security maturities accordingly Some try to time interest rate peaks by following a counter-cyclical investment strategy defined by changes in loan demand and the yield curve’s shape Active Strategies Over the Business Cycle The strategy entails both expanding the investment portfolio and lengthening maturities at the top of they business cycle, when both interest rates and loan demand are high Note that the yield curve generally inverts when rates are at their peak prior to a recession Alternatively, at the bottom of the business cycle when both interest rates and loan demand are low, a bank contracts the portfolio and shorten maturities The Impact of Interest Rates on the Value of Securities with Embedded Options Issues for Securities with Embedded Options Callable agency securities or mortgagebacked securities have embedded options To value a security with an embedded option, three questions must be addressed Is the investor the buyer or seller of the option? How and by what amount is the buyer being compensated for selling the option, or how much must it pay to buy the option? When will the option be exercised and what is the likelihood of exercise? Price-Yield Relationship for Securities with Embedded Options The Roles of Duration and Convexity in Analyzing Bond Price Volatility Recall that the duration for an option- free security is a weighted average of the time until the expected cash flows from a security will be received P Duration - P i (1 i) i P - Duration P (1 i) The Roles of Duration and Convexity in Analyzing Bond Price Volatility Yield % Price Price - $10,000 Duration 8 10,524.21 524.21 5.349 9 10,257.89 257.89 5.339 10 10,000.00 0.00 5.329 11 9,750.00 (249.78) 5.320 12 9,508.27 (491.73) 5.310 $ Price 10,524.21 10,507.52 Actual price increase is greater when interest rates fall for option free bonds. 10,000.00 Price-yield curve Tangent line representing the slope at 10% 8% 10% Interest Rate % The Roles of Duration and Convexity in Analyzing Bond Price Volatility From the previous slide, we can see: The difference between the actual price-yield curve and the straight line representing duration at the point of tangency equals the error in applying duration to estimate the change in bond price at each new yield For both rate increases and rate decreases, the estimated price based on duration will be below the actual price The Roles of Duration and Convexity in Analyzing Bond Price Volatility From the previous slide, we can see: Actual price increases are greater and price declines less than that suggested by duration when interest rates fall or rise, respectively, for option-free bonds For small changes in yield the error is small For large changes in yield the error is large The Roles of Duration and Convexity in Analyzing Bond Price Volatility Convexity The rate of change in duration when yields change It attempts to improve upon duration as an approximation of price ΔPrice Due to Convexity Convexity(i2 )Price This is positive feature for buyers of bonds because as yields decline, price appreciation accelerates The Roles of Duration and Convexity in Analyzing Bond Price Volatility Convexity As yields increase, duration for option free bonds decreases, once again reducing the rate at which price declines This characteristic is called positive convexity The underlying bond becomes more price sensitive when yields decline and less price sensitive when yields increase Impact of Prepayments on Duration and Yield for Bonds with Options Embedded options affect the estimated duration and convexity of securities For example, prepayments will affect the duration of mortgage-backed securities Market participants price mortgage-backed securities by following a 3-step procedure: Estimate the duration based on an assumed interest rate environment and prepayment speed Identify a zero-coupon Treasury security with the same (approximate) duration. The MBS is priced at a mark-up over the Treasury Impact of Prepayments on Duration and Yield for Bonds with Options The MBS yield is set equal to the yield on the same duration Treasury plus a spread The spread can range from 50 to 300 basis points depending on market conditions The MBS yields reflect the zero-coupon Treasury yield curve plus a premium Effective Duration and Effective convexity Both are used to estimate a security’s price sensitivity when the security contains embedded options Pi- - Pi Effective Duration P0 (i i- ) Pi- Pi 2P * Effective Convexity P * [0.5(i i- )] 2 Where: Pi- = price if rates fall Pi+ = price if rates rise P0 = initial (current) price P* = initial price i+ =initial market rate plus the increase in rate i- = initial market rate minus the decrease in rate Effective duration and Convexity Example: Consider a GNMA pass-through which has 28-years and 4-months weighted average maturity The MBS is initially priced at 102 and 17/32nds to yield 6.912%, at 258 PSA At this price and PSA, MBS has an estimated average life of 5.57 years and a modified duration of 4.01 years Effective duration and Convexity Example: Assume a 1% decline in rates will accelerate prepayments and lead to a price of 102 while a 1% increase will slow prepayments and produce a price of 103 The effective duration and convexity for this security are thus: Effective GNMA duration = [102-103]/ 102.53125x(.05921 - .07921) = -0.4877 years Effective GNMA convexity = [102+103-2 x (102.53125)]÷102.53125[0.52(.02)2] = -6.096 years Positive and Negative Convexity Option-free securities exhibit positive convexity because as rates increase, the percentage price decline is less than the percentage price increase associated with the same rate decline Securities with embedded options may exhibit negative convexity The percentage price increase is less than the percentage price decrease for equal negative and positive changes in rates Total Return Analysis An investor’s actual realized return should reflect the coupon interest, reinvestment income, and value of the security at maturity or sale at the end of the holding period When a security carries embedded options, these component cash flows will vary in different interest rate environments Total Return Analysis If rates fall and borrowers prepay faster than originally expected: Coupon interest will fall Reinvestment income will fall The price at sale (end of the holding period) may rise or fall depending on the speed of prepayments Total Return Analysis When rates rise Borrowers prepay slower Coupon income increases Reinvestment income increases The price at sale may rise or fall Total Return Analysis for a Callable FHLB Bond Total Return Analysis for a Callable FHLB Bond Option-Adjusted Spread The standard calculation of yield to maturity is inappropriate with prepayment risk Option-adjusted spread (OAS) accounts for factors that potentially affect the likelihood and frequency of call and prepayments Static spread is the yield premium, in percent, that (when added to Treasury zero coupon spot rates along the yield curve) equates the present value of the estimated cash flows for the security with options equal to the prevailing price of the matched-maturity Treasury Option-Adjusted Spread OAS represents the incremental yield earned by investors from a security with options over the Treasury spot curve, after accounting for when and at what price the embedded options will be exercised. OAS analysis is one procedure to estimate how much an investor is being compensated for selling an option to the issuer of a security with options. OAS is often calculated as an incremental yield relative to the LIBOR swap curve. Option-Adjusted Spread The approach starts with estimating Treasury spot rates (zero coupon Treasury rates) using a probability distribution and Monte Carlo simulation, identifying a large number of possible interest rate scenarios over the time period that the security’s cash flows will appear Option-Adjusted Spread The analysis then assigns probabilities to various cash flows based on the different interest rate scenarios For mortgages, one needs a prepayment model and for callable bonds, one needs rules and prices indicating when the bonds will be called and at what values Steps in Option-Adjusted Spread Calculation Rate Volatility Estimates (Variance) Current Treasury Curve (Mean) Distribution of Interest Rates Other Prepayment Factors Prepayment Model Security-Specific Information: Coupon Rate, Maturity, etc. Possible Cash Flows from Mortgage Security Market Price of Mortgage Security Find Spread over Treasury Rates Such That Market Price = Present Value of Cash Flows Option-Adjusted Spread Shock Rates Up and Down Calculate Duration and Convexity Option-Adjusted Spread Analysis for a Callable FHLB Bond Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities Interest on most municipal securities is exempt from federal income taxes and, depending on state law, from state income taxes Some states exempt all municipal interest Most states selectively exempt interest from municipals issued in-state but tax interest on out-of-state issues Other states either tax all municipal interest or do not impose an income tax Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities Capital gains on municipals are taxed as ordinary income under the federal income tax code This makes discount municipals less attractive than par municipals because a portion of the return, the price appreciation, is fully taxable When making investment decisions, portfolio managers compare expected risk-adjusted after-tax returns from alternative investments Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities After-Tax and Tax-Equivalent Yields Once the investor has determined the appropriate maturity and risk security, the investment decision involves selecting the security with the highest after-tax yield Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities After-Tax and Tax-Equivalent Yields Tax-exempt and taxable securities can be compared as: R m R t (1 t) where Rm = pretax yield on a municipal security Rt = pretax yield on a taxable security t = investor’s marginal federal income tax rate Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities After-Tax and Tax-Equivalent Yields Example Let: Rm = 5.75% Rt = 7.50% Marginal Tax Rate = 34% The investor would choose the municipal because it pays a higher after tax return: Rm Rt = 5.75% after taxes = 7.50% (1 - 0.34) = 4.95% after taxes Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities Marginal Tax Rates Implied in the Taxable - Tax-Exempt Spread If taxable securities and tax-exempt securities are the same for all other reasons then: t* = 1 - (Rm / Rt) where Rm = pretax yield on a municipal security Rt = pretax yield on a taxable security Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities Marginal Tax Rates Implied in the Taxable - Tax-Exempt Spread t* represents the marginal tax rate at which an investor would be indifferent between a taxable and a tax-exempt security equal for all other reasons Higher marginal tax rates or high tax individuals (companies) will prefer taxexempt securities Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities Example Let: Rm Rt = 5.75% = 7.50% Marginal Tax Rate = 34% 5.75% t 1 23.33% 7.50% * An investor would be indifferent between these two investment alternatives if her marginal tax rate were 23.33% Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities Municipals and State & Local Taxes The analysis is complicated somewhat when state and local taxes apply to municipal securities: m Rm (t t ) R t [1 (t t m )] Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities Municipals and State & Local Taxes Many analysts compare securities on a pre-tax basis To compare municipals on a tax equivalent basis (pre-tax): Rm (t t m ) Tax Equivalent Yield 1 (t m t) Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities Deductibility of Interest Expense Prior to 1983, banks could deduct the full amount of interest paid on liabilities used to finance the purchase of muni's After 1983 15% was not deductible and after 1984 20% was not deductible Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities Deductibility of Interest Expense The 1986 tax reform act made 100% not deductible except for qualified muni's, small issue (less than $10 million) The loss of interest expense deductibility is like an implicit tax on the bank's holding of municipal securities Comparative Yields on Taxable versus TaxExempt Securities Deductibility of Interest Expense To calculate after tax yields on muni's, if interest expense is not fully deductible, calculate the bank’s effective tax rate on municipals (tm): tm Pooled %Not t Interest Deductable Cost Rmuni State and Local Comparative Yields on Taxable versus Tax-Exempt Securities Example: Assume t =34%, 20% Not Deductible 7.5% Pooled Interest Cost Rmuni = 7%. t muni (0.34) (0.20) (0.075) 0 6.38% 0.08 at Rmuni 8.0 (1 0.0638) 7.49% Comparison of After-Tax Returns on Taxable and TaxExempt Securities for a Bank as Investor After-Tax Interest Earned on Taxable versus Exempt Securities Taxable $ 10,000 10.00% $ 1,000 $ 340 $ 660 Par Value Coupon Rate Annual Coupon interest Federal income taxes (34%) After-tax income Municipal $ 10,000 8.00% $ 800 $0 $ 800 After-Tax Interest Earned Recognizing Partial Deductibility of Interest Expense Par Value Coupon Value Annual coupon interest Federal income taxes (34%) Polled interest expense (7.5%) Lost interest deduction (20%) Increased tax liability (34%) Effective after-tax interest income $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 10,000 0 1,000 340 750 660 $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ 10,000 0 800 750 150 51 749 After-Tax Interest Earned, Recognizing Partial Deductibility of Interest Expense: Individual Asset Factors affecting allowable deduction: Total interest expense paid $ Average amount of assets owned $ 20,000,000 Average amount of tax exempt securities owned: $ Weighted average cost of financing 1,500,000 800,000 7.50% Nondeductible interest expense: Pro rata share of interest expense to carry muni's Nondeductible interest expense (20%) Deductible interest expense: $1,500,000 - $12,000 = 4.00% $ 12,000 $ 1,488,000 The Impact of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA 1986) The TRA of 1986 created two classes of municipals Qualified Nonqualified Municipals After 1986, banks could no longer deduct interest expenses associated with municipal investments, except for qualified municipal issues The Impact of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA 1986) Qualified versus Non-Qualified Municipals Qualified Municipals Banks can still deduct 80 percent of the interest expense associated with the purchase of certain small issue publicpurpose bonds (bank qualified) Nonqualified Municipals All municipals that do not meet the qualified criteria The Impact of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA 1986) Qualified versus Non-Qualified Municipals Municipals issued before August 7, 1986, retain their tax exemption; i.e., can still deduct 80 percent of their associated financing costs (grandfathered in) The Impact of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA 1986) Example: Implied tax on a bank’s purchase of nonqualified municipal securities (100% lost deduction) Assume t =34% 20% not deductible 7.5% pooled interest cost Rmuni = 7% t muni (0.34) (1.00) (0.075) 0 31.88% 0.08 at Rmuni 8.0 (1 0.3188) 5.45% Strategies Underlying Security Swaps Active portfolio strategies also enable banks to sell securities prior to maturity whenever economic conditions dictate that returns can be earned without a significant increase in risk When a bank sells a security at a loss prior to maturity, because interest rates have increased, the loss is a deductible expense At least a portion of the capital loss is reduced by the tax-deductibility of the loss Evaluation of Security Swaps Par Value Market Value Remain Maturity Semiann Coupon YTM A. Classic Swap Description Sell US Trea bonds @ 10.50% Buy FHLMC bons @ 12.20% $2,000,000 $1,926,240 $1,952,056 $1,952,056 3 3 $105,000 $119,075 12.00% 12.20% B. Swap with Minimal Tax Effects Sell US Treas bons @ 10.50% Sell FNMA @ 13.80% Total Buy FNMA @ 13.00% $2,000,000 $3,000,000 $5,000,000 $5,000,000 3 4 $105,000 $207,000 $312,000 $325,000 $ 13,000 12.00% 13.00% $1,926,240 $3,073,065 $4,999,305 $5,000,000 1 12.00% C. Present Value Analysis Period 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Treas Cash flow $1,926,240 ($105,000) ($105,000) ($105,000) ($105,000) ($105,000) ($2,105,000) Tax savings $25,816 FHLMC ($1,952,056) $119,075 $119,075 $119,075 $119,075 $119,075 $2,071,132 Difference: $0 $14,075 $14,075 $14,075 $14,075 $14,075 ($33,868) 14,075 47,944 14,075 $35,380 t 6 1.061 t 1 1.061 6 PV Security Swap Example Tax Savings: = (2,000,000 - 1,926,240) * 0.35 = 25,816 After Tax Proceeds = 1,926,240 + 25,816 = 1,952,056 Present Value of the Difference: 14,075 47,944 14,075 PV $35,380 t 6 1.061 t 1 1.061 6 Strategies Underlying Security Swaps In general, banks can effectively improve their portfolios by: Upgrading bond credit quality by shifting into high-grade instruments when quality yield spreads are low Lengthening maturities when yields are expected to level off or decline Obtaining greater call protection when management expects rates to fall Strategies Underlying Security Swaps In general, banks can effectively improve their portfolios by: Improving diversification when management expects economic conditions to deteriorate Generally increasing current yields by taking advantage of the tax savings Shifting into taxable securities from municipals when management expects losses Bank Management, 6th edition. Timothy W. Koch and S. Scott MacDonald Copyright © 2006 by South-Western, a division of Thomson Learning Managing the Investment Portfolio Chapter 13 William Chittenden edited and updated the PowerPoint slides for this edition.