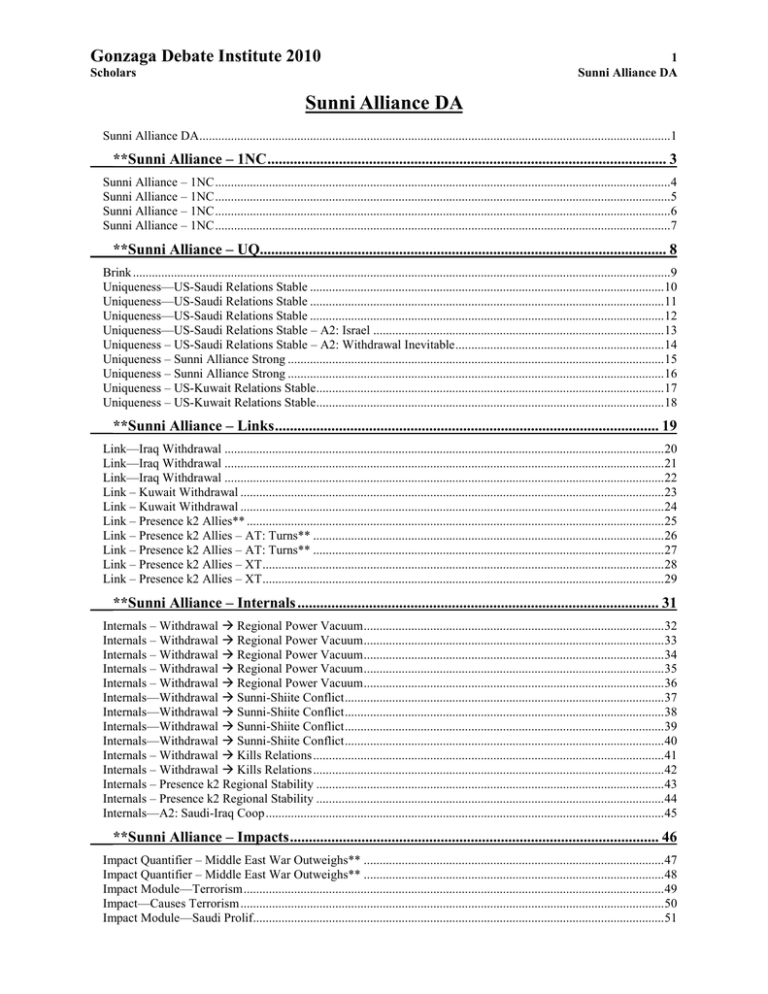

Sunni Alliance – 1NC - Open Evidence Archive

advertisement