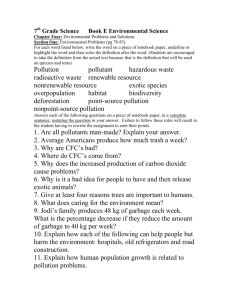

environmental racism

advertisement

The Safety Standard Introduction The safety standard: fairness rather than efficiency Rejects a benefit-cost approach to decisions about the “correct” amount of pollution People have a right to protection from unsolicited, significant harm to their immediate environment An Efficiency Argument for a Safety Standard? Many important benefits of protection from pollution are often left out of benefit-cost analyses because they cannot be measured If material growth in our society feeds conspicuous consumption, fueling a rat race, then no one is better off If the costs of protection are overstated by this rat race, while the benefits are understated, then safe regulation may in reality meet a benefit-cost test Defining “Safety” In practice, The U.S. EPA considers risk below 1 in 1 million for large populations to be “safe” Risks greater than 1 in 10,000 are considered “unsafe” Risks that fall in between are regulated based on an informal benefit-cost analysis and statutory requirements Defining Safety Determining the exact risk amount for things such as cancer can only be done with substantial margins of error, and “safety” is thus often determined through the give and take of politics Policy and the Safety Standard A safety standard remains the stated goal of much environmental policy: laws covering air, water, and land pollution require cleanup to “safe” levels, period There is no mention of a benefit-cost test in the legislation Ultimately, however, clean-up costs often play a role in the political determination of “safe” pollution levels Is Accepting Some Risk the same as an Efficiency Approach? Declaring a safety standard and then adopting it to economic feasibility in certain cases is different from, and will generally result in less pollution than, an efficiency standard Can safety be sold? One study asked residents of a Nevada community about their willingness to accept annual tax credits of $1,000, $3,000, and $5,000 per person in exchange for the siting of a potentially dangerous hazardous waste facility nearby The numbers of people considering accepting the compensation did not increase as the level of compensation increased Instead, respondents who perceived the risk to be too high viewed the rebates not as inadequate, but as inappropriate The Safety Standard Social Welfare Function Recall Tyler and Brittany wrangling over smoking in the office: SW = UTyler(#CigsT, $T) = UBrit(w * #CigsT, $B) Smoking is a bad to Brittany and a good to Tyler. If the weight given to w were large enough, it might justify banning smoking altogether Smoking in Public Places Should smoking be banned in public places? This is an issue for voters and courts to decide What the safety standard maintains is that in the absence of a “compelling” argument to the contrary, damage to human health from pollution ought to be minimal The Safety Standard: Objections Inefficient? Not Cost-Effective? Regressive? Often Often Maybe The Safety Standard: Inefficient The safety standard is, by definition, inefficient Efficiency advocates claim that enshrining environmental health as a “right” involves committing “too many” of our overall social resources to environmental protection Air toxics regulation The 1990 amendments to the Clean Air Act were designed to control the emissions of hazardous air pollutants The law required firms to impose control technology that would reduce risks to below the 1 in 10,000 level Total costs were estimated at $6 to $10 billion per year, with benefits less than $4 billion per year Air toxics regulation Polls indicated that 80% of Americans supported the act despite this benefit-cost disparity Does this indicates that American voters view environmental health as a “rights” issue? Landfill Policy The EPA’s regulation for landfills to protect people who depend on contaminated groundwater were only predicted to reduce cancer cases by only two or three over the next 300 years Potential benefits not quantified include Increased ease of siting landfills Reduced damage to surface water Fairness to future generations Overall reduction in waste generation and related “upstream” pollution The regulations would cost about $5.8 billion or nearly $2 billion per cancer case reduced Inefficient Regulations Regulations that protect small groups of people from risk will almost always be inefficient, since even relatively high risks will not generate many casualties Air toxics and the EPA’s landfill regulations are classic situations in which efficiency and fairness conflict The Safety Standard: Not Cost Effective? The second criticism leveled at the safety standard is its lack of costeffectiveness--achieving a goal at the lowest possible cost If “safety” is the goal, then extreme measures may be taken to attack “minimal” risk situations instead of high risk situations Superfund and Asbestos Tens of millions of dollars have been spent trying to purify seldom used groundwater at toxic spill sites under the Superfund legislation Critics have argued that redirecting the funds would be a better use of resources, for example: Children have about a 5 in 1 million chance of contracting lung cancer from attending a school built with asbestos Redirecting funds from superfund clean-up to asbestos removal could save more lives A Safety Proponent’s Response The limits to dealing with these problems are not limited resources, but a lack of political will Funds freed up from “overcontrol” in the pollution arena are more likely to be devoted to affluent consumption than to environmental protection Risk-Benefit Analysis Authorities use risk-benefit studies to compare the cost-effectiveness of different regulatory options The common measure used in this approach is lives saved per dollar spent This helps avoid devoting resources to an intractable problem, but it does not mean backing away from safety as a goal The Safety Standard: Regressive? Safety standards will generally be more restrictive than efficiency standards; as a result, they lead to greater sacrifice of other goods and services Some are concerned that a people will fall below a decent standard of living as a result of overregulation Suppose we switched from a safety standard to an efficiency-based standard. Would the poor be made better off? The Safety Standard: Regressive? Because much pollution is generated in the production of necessities, the cost of environmental regulation is borne unevenly Pollution control generally has a regressive impact on income distribution, meaning that the higher prices of consumer goods induced by regulation take a bigger percentage bite of the incomes of poor people than of wealthier individuals Costs of Pollution Control Global warming (CO2) tax of $70 per ton: control: Energy expenses up $215 per year, or 11% for the poorest 10% of US households Energy expenses up $1,475, or 5% for the richest 10% of US households. Environmental Racism The racial inequity in siting of hazardous facilities is called environmental racism Environmental racism has sparked a political movement called the environmental justice movement The Effect of Pollution Control on Low Income Communities Poor, working-class, and minority people pay more, relative to their income, for pollution control. They also receive more benefits Hard to determine whether pollution control results in net benefits or net costs on the lower half of the income distribution For important issues such as a carbon tax to slow global warming, distributional issues need to be weighed carefully Safety versus Efficiency: The Summers Memo In an internal memorandum to his staff, then chief economist at the World Bank, Lawrence Summers wrote: “Just between you and me, shouldn’t the World Bank be encouraging more migration of the dirty industries to the [less-developed countries]?…I think the economic logic behind dumping a load of waste in the lowest-wage country is impeccable and we should face up to that.” Yikes!! We have defined this “narrow” view as the efficiency view. Is it is morally defensible? Possibly, if toxic trade in fact makes all parties better off… Siting Hazardous Waste Facilities: Safety Versus Efficiency “Locally unwanted land uses” or LULUs refer to sites for the disposal of waste--hazardous, radioactive, or just non-hazardous municipal waste LULUs impose negative externalities on their neighbors from potential hazards of exposure to decreased land values By definition, communities do not want LULUs, and the wealthier the community, the higher the level of safety the community will demand Compensation for LULUs Society as a whole benefits greatly from having toxic facilities One solution to the problem of LULUs would then be to monetarily compensate communities with LULUs This compensation could then pay for schools, hospitals, libraries, etc. Poorer communities would accept lower compensation levels than wealthier communities This could lead to a “trade” in LULUs Efficiency and Toxic Trade Efficiency and Toxic Trade Due to lower incomes, a poor country has a marginal benefit of cleanup schedule lying below that of a rich country Because current pollution levels are relatively low in the poor country, the marginal benefits of cleanup are also low relative to a rich country Transferring 10% of the waste from a rich country to a poor country reduces monetary damages in the rich country more than it increases damages in the poor country The poor country would then be compensated for its damages and overall monetary damages from the pollution will have been reduced by trade Winners and Losers Winners: Those in wealthy countries no longer exposed to waste, those around the world who can buy cheaper products, firm managers and stock holders, those in poor countries working at dump sites Losers: poor country individuals, alive and yet unborn, who contract cancer and other diseases, and those who rely on natural resources that may be damaged in the transport and disposal process Everybody Wins? Because dumping toxics is indeed efficient, the total monetary gains to the winners outweigh the total monetary loss to the losers In theory, the winners could compensate the losers, and everyone would be made better off In practice, complete compensation is unlikely Problems With Toxic Trade The majority of benefits from the dumping will flow to the relatively wealthy while the poor will bear the burden of costs The political structure in many developing countries is far from democratic, and highly susceptible to corruption. Few poor countries have the resources for effective regulation. Stiff regulation or high taxes will increase the rate of illegal dumping; unrestricted trade in waste may thus lower the welfare of the recipient country Safety Standard and the Siting of LULUs A politically acceptable definition of “safety” cannot be worked out, since a small group bears the burden of any risk: Nobody wants a LULU in his or her backyard Compensation thus plays role in the siting of hazardous facilities Firms and governments will seek out poorer communities with lower compensation packages For the Benefit of a Majority To ensure a majority of people benefit from the siting of LULUs: Government must be capable of providing effective regulation An open political process combined with well-informed, democratic decision making is needed in the siting process Safety Versus Efficiency The safety standard relies on a liberty argument, putting heavy weights on the welfare reduction from pollution As a result, a stricter pollution standard is called for than is implied by the efficiency standard Efficiency advocates attack the “fairness” argument of safety advocates by arguing that the safety standard is regressive-although this is difficult to prove or refute in general Costs, Benefits, Efficiency, and Safety