docx

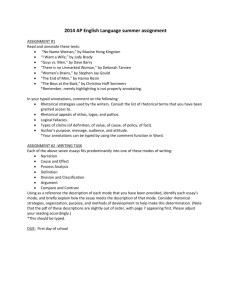

advertisement

How Science Persuades WRTG 3030—Writing on Science & Society Petger Schaberg E-mail: Petger.Schaberg@colorado.edu (M-F) Office phone: #303-492-5429 Fall 2010—Sections 29, 33 Office Hrs: T & Th 10:55-12:25 & by appt. Office: Temp Building 1-110 Course Description Welcome to “How Science Persuades”—a rhetorically based WRTG 3030 Writing Seminar that examines the relationship between science & society in shaping our contemporary world. The discipline of Rhetoric and Composition is particularly well suited for this inquiry in that it gives students the sophisticated rhetorical perspectives that will allow them to utilize a toolkit of strategies for the purpose of creating persuasive scientific writing for a range of important contemporary audiences. Selected texts—both alphabetic and image-based—from scientific journals, from the philosophy of science, from the politics of science, from mass media & popular culture, and from rhetorical theory, will ground our investigation into the scientific method and its foundational tenants of observation, evidence, and experiment. This approach emphasizes the importance of powerful persuasive writing for practicing scientists, engineers, and corporate researchers—as well as for social scientists and those in humanities—in light of the complex ways that scientific thought makes its appeals to scientific audiences, to civic and policy-related audiences, to the business community, and to the broader target of popular culture. Upon fulfilling the course requirements, students will have developed an enhanced rhetorical awareness that will allow them to be skilful writers and interpreters both inside and outside the specific scientific disciplines that are so crucial to contemporary global society. Our achievement will include, but is not limited to: Applying rhetorical principles and practices to scientific writing for a variety of contemporary audiences. Directing disciplinary expertise within and beyond your discipline. Developing your understanding of various professional genres and forms. Work collaboratively on team projects, collaborative writing, and peer review. Understand that substantive revision is the cornerstone of fine writing. Develop the critical thinking skills and a toolkit of strategies that will allow you to write persuasively from project to project, and from discipline to discipline. In a course such as this a flood of curious questions naturally arises: How are scientific “facts” translated into more value-laden written genres such as grant proposals, business funding requests, policy initiatives, K-College education, or the mass media? Is science responsible for the technological innovations--such as the Deepwater Horizon oil rig--that it spins off? Should governments openly support science and innovation--and if so, how should scientists make the political appeals necessary to make their case? Is gender bias prevalent in research science? How does science contribute—or not contribute—to our individual worldviews? Does the peer review process, as Kuhn has suggested, bias the direction that particular scientific disciplines take in the short run? Is this “corrected” over time, or not? How is proposal writing different from journal articles? How can scientists communicate with specialists in different fields? By examining the rhetorical values of a range of complex scientific cultural artifacts in a range of media, students of WRTG 3030 “How Science Persuades” will be empowered to engage in successful scientific writing for scientists, for popular culture, for the business world, for civic audiences, and to shape the marketplace of ideas with great persuasive skill. Why is this Class a “Core Course”? This 3000-level Program for Writing & Rhetoric seminar satisfies upper-division core requirements in various CU-Boulder schools and colleges because it extends rhetorical knowledge and writing skills through theoretical perspectives and by addressing specialized disciplinary communities—not only those of the hard sciences and engineering, but also in the social sciences and humanities.. In doing so, this course also meets the State of Colorado “Guaranteed Transfer” goals for an Advanced Writing Course (GT-CO3): Extended Rhetorical Knowledge Readings from the course website will introduce a range of rhetorical texts that give students a greater awareness of rhetorical strategy and how it informs their own persuasive goals. Theorists such as Jeanne Fahnestock, Thomas Kuhn, Michael Berube, Stephen Toulmin, Leah Ceccarelli, Steven French, Jerome Kagan, Geeta Verma, Jonathan Marks, Martin Bauer, John Gage, and Aristotle, will guide our discussions, offering the critical basis for the writing projects that form the foundation of the course. These texts have the advantage of introducing both specific rhetorical disciplines—engineering, biology, the history of science, physics, anthropology , rhetoric, and composition studies—as well as opening the student analysis to unique interdisciplinary modes in both the social sciences and the humanities, including history, ecology, geography, politics, and religion. On-line sites for writing in the sciences will help us clarify such issues such as voice, tone, and structure are crucial to successful scientific persuasion. Since alphabetic texts, are not the sole means by which science is communicated to its various audiences, the course naturally considers the role of rhetorical knowledge implicit in other media. Drawing from artifacts as wide-ranging as government NASA videos, science and technology websites, corporate advertising, popular film, research videos, television culture, science blogs, the visual arts, psychology, politics, and emerging technologies, students will understand that “science implies a recognition of audience” and that they must be ready to shift the genre of their writing accordingly. Such a broad range of technologies encourages a multi-modal approach to writing and will encourage us to investigate the underlying persuasive strategies of science with fresh eyes. Writing processes In order to realize their best work, those engaged in scientific discourse take it to heart that critical writing is an ongoing process, extending over multiple drafts. In this class, each assignment has been designed to give students a range of strategies for drafting, revising, and editing their work. This expertise will allow us to approach the draft process—not with dread or foreboding—but with a sense of it as both beneficial and pragmatic. A serious investigation as to the actual procedures of library research, using both specialized and crossdiscipline approaches, will aid students in learning to evaluate sources for accuracy, relevance, and bias. Since the workshop structure of the course aligns critical reading with improved critical writing, students will come to see themselves as an important part of a community of writers who offer sophisticated criticism, editing, and macro analysis in a respectful and cooperative environment. This discourse community will contrast with the wide range of audiences addressed in the various student projects: scientific audiences, civic and policy-related audiences, the business community, and the broader target of popular culture. Instructor feedback will further compliment small group observations. Through these expanded communities, some hopefully enduring beyond the course itself, students will come to see the art and craft of scientific writing and the persuasive structures that serve as their foundation. Writing Conventions Another crucial aspect of a rhetorical study of scientific writing is to grapple with writing conventions. Friedland’s work on science proposals, Beer’s work for engineers, and Robert Goldbort’s work for the broader sciences will help us to design our writing in the appropriate forms. Gopen and Swan’s, “The Science of Scientific Writing” will further clarify our final discipline-specific article. Fine writers develop a sense of the specific audience conventions and use them—either by acceptance or resistance—to further develop their persuasive endeavor. Using a range of texts, cultural artifacts, and our class essays, students will learn to use specialized language, and to be aware of a range of formats and documentation styles. Our ongoing concern with issues of writing technique—syntax, grammar, punctuation, spelling, and style—will always be grounded in the sense that it contributes to our concern for meeting the expectations of particular scientific writing conventions. Slang, outright errors, humor, or a markedly emotional style are not in and of themselves problematic—but may create (or erase) problems of authorial ethos for particular audiences. Online peer feedback, instructor criticism, power point presentations, video, and in-class workshops will compliment our understanding of writing conventions and empower students to make well-reasoned decisions regarding the structure, style, and content of their work. Content Comprehension & Composition (Effective Application) A course investigating the relationship between science and society would have little traction if it did not demand at its foundation a comprehensive content knowledge of the particular artifacts under consideration. Essays by J B S Haldane, Heisenberg, Alan Turing, Carl Sagan, Garrett Hardin, and others will ground us in the specific content of the interface between Science and the broader contemporary society which it seeks to address. Further Prize winning essays from the AAAS website, and from the “Nature”, and “Science” journals will help to establish the very highest standards in scientific research. Databases such as QuickSciTech, ScienceDirect, will also provide clear examples of cross-disciplinary audiences. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers and other Science and Technology websites such as NASA, NIST, NOAH, NIH, NSF, EPA, USFS, USGS, NATO Scientific and Environmental Affairs Division, etc. will further contribute to the range of real world persuasive texts at the interface of Science and Society. The incremental progression of the three major assignments has been designed to heighten the awareness of the relationship between specialized content and various audiences. The wide range of texts and the equally broad range of media under consideration will allow students to adapt their projects to the needs and expectations within specific disciplines. Most major and minor assignments are focused on real-world audiences—including civic, academic audiences in the hard sciences, business, the social sciences, and even popular culture. This approach will allow us to write in a disciplinary or specialized rhetorical situation, as well as to address secondary audiences. Technology & Persuasion As the global technological “commons” grows ever more pronounced, it is important that a rhetoric & writing class utilize a range of technologies in addressing both the form and content of rhetorical persuasion. To this end we will regularly use the unique medium of on-line interaction at our class wiki at Petgers1250wikis.wikispaces.com. This format will extend our important class interactions, allowing student peers an on-line forum for further developing their ideas. In addition, our disciplinary conference presentations in Powerpoint or Prezi, our work with the rhetoric of graphing, and our use of persuasive visual images will allow us to move beyond the analysis of visual media, and to actually pursue successful persuasion in the multimodal media themselves. This mastery of technological discourse should give students an edge in both their academic careers and their future vocations. Assignments Since the course aspires to give students rhetorical strategies for improving scientific disciplinary discourse while at the same time mastering how scientists how to convince political audiences, the popular media, and various the funding entities of their views, the assignments in this course have been carefully designed to offer the maximum efficiency, and motivation. With French, Toulmin, and Fahnestock as our guides, we will write several short one-page rhetorical essays that re-introduce techniques of thesis-building, evidential support, organization, and rhetorical awareness, leading to a 5-6-page Rhetorical Essay (15%) on the image science in contemporary culture. A 6-8 page Mock or Real Research Proposal (20%), proposing a problem or hyposthesis to be tested, solving a real science problem for a real world scientific funding audience (for UROP or other real funding agency, or for the mock funder I will provide). This project will help us to articulate the rhetorical practices scientists engage in with grant agencies, funding bodies, and corporate culture. The second part of this assignment will ask students to reform this proposal into a viable 2-page Mass Media Interview 5%)—a form that may demand a more emotional means of persuasion. In shifting from writing about science to writing in a specific discipline, we can engage our learning to its maximum with an 10-15 page Scientific Research Essay (30%). We will present these as The rhetorical double, if you will, of this evidential essay will be to re-cast it as a 10 minute Power point conference presentations. (5%). For the Final, due December 15th. Students will complete interviews with specialists in their particular field, and generate a 3-4 page Professional Writing Expectations Statement (5%), in which they elucidate the writing forms and practices that will be expected of them upon entering their field as a professional. Other Grading Categories Quizzes, Peer Reviews, Exercises, and Worksheets: 10 %. Class Participation and Preparation: 10 %. Required Texts Steven French’s Science: Key Concepts in Philosophy, David Ferry’s, Gilgamesh; Blade Runner—not for purchase, and the many articles available on our course blog at [[ petgers3030wiki.wikispaces.com ]]. Online sources will include numerous federal science and technology websites such as NASA, NIST, NOAH, NIH, NSF, EPA, USFS, USGS, NATO Scientific and Environmental Affairs Division, etc., private corporations, and foundations, the AAAS website, CU’s UROP and other academic sites, and several nationally recognized rhetoric and composition websites including: The New Mexico Literacy Project, The Purdue University Owl http://owl.emglish.purdue.edu/owl/ & Silva Rhetoricae http://humanities.byu.edu/rhetoric/Silva.htm. Attendance, Participation, & Classroom Behavior Because we are committed to developing a community of talented writers, attendance and active participation are important responsibilities. Please e-mail or call if you cannot attend class. Get notes from a classmate, THEN discuss with me what you do not understand. If you miss a class you will be expected to be fully prepared for the next class. Look ahead in the syllabus schedule and be prepared. Class attendance is critical because I will explain assignments in class and because class discussions will help us to develop successful writing projects. One or no absences will be rewarded with extra credit for your final grade. For two or three misses there will be no extra credit and no penalty. For each absence over three, a onegrade-for-each-absence penalty will be instituted--(B-=C+ for four misses; B-=C for five). There will be no penalty for being over the limit only if all absences are due to medical or religious reasons, and you have presented me with an official excuse for each of them. Use these unpenalized absences for a time when you will really need them—a late illness, falling in (or out) of love, a night of icy genius on the moon-slick Colorado slopes. Seven absences—even when excused—may prevent you from passing the course. I will make every attempt to deal fairly with students who, because of religious obligations, have conflicts with scheduled exams, assignments or required attendance if they provide me with written documentation. (See more information at http://www.colorado.edu/policies/fac_relig.html ). As it constitutes a disruption of our work, lateness will not be tolerated. Three late arrivals will be counted as one missed class. If you are late you will be marked absent and it will be your responsibility to have me strike that absence from the record. More generally, we will follow normal rules of etiquette in being respectful of each other’s opinions and values. Please don’t hold conversations while others are speaking. Learning is interactive—we must interact during the class discussions in order to benefit. As lap top computers are a great temptation to dally in the eternal ether of internet bliss, I ask that you shut them for the entire class period—unless needed for internet assignments—which will be fairly frequent. It follows that there should be no cell phones, no newspaper reading, no texting, no e-mail, no noisy food. As much as we love animals, please do not bring them to class—they are an inevitable disruption. Keep in mind that students and faculty have responsibility for maintaining an appropriate learning environment. Faculty have the professional responsibility to treat students with understanding, dignity and respect, to guide classroom discussion and to set reasonable limits on the manner in which students express opinions. Students who fail to adhere to behavioral standards may be subject to discipline. For more information about what the university has to say about unacceptable classroom behavior, please go to the web at http://www.colorado.edu/policies/classbehavior.html http://www.colorado.edu/studentaffairs/judicalaffairs/code.html3studetn_code Writing Workshops The writing workshop is an exciting way to develop writing skills. By carefully reading and commenting on each other’s work—in an open forum that invites frank discussion—we will develop the critical and stylistic skills we need to succeed as writers. Student drafts will regularly be work-shopped in class and will serve as primary texts. Therefore, each of us must take it as a personal responsibility to come prepared with careful critical feedback on a regular basis. Please have drafts ready for and online circulation 24 hours prior to class discussion. Drafts are mandatory but only final drafts will be graded. Please type all drafts. Your participation grade in the course (as well as the quality of your work) will likely plummet if you do not submit your workshop drafts on time. I cannot accept final papers that have not been reviewed in small group workshops during the assignment—“First draft” final essays are unacceptable and will receive a failing grade. There are deadlines in the “real world” and there are deadlines in this class—deadlines which can potentially enhance both our creativity and our commitment to doing our best work—hence late papers cannot be accepted. As per CU guidelines for a T/Th course, we will have an average of 3 hours of homework per class. Miscellaneous Wikispaces As we will use a on-line wiki for some course discussions, you will be expected to have a viable e-mail address, and to check the Wikispaces site at [[ petgers3030wiki.wikispaces.com ]] for discussion prompts, updates and revised assignments. Honor Code. All students of the University of Colorado at Boulder are responsible for knowing and adhering to the academic integrity policy of this institution. Violations of this policy may include: cheating, plagiarism, aid of academic dishonesty, fabrication, lying, bribery, and threatening behavior. Plagiarism will not be tolerated; the paper will receive an automatic F, and your case will be reported to the Honor Code Council. (honor@colorado.edu: 303 725-2273). Students found to be in violation will be subject to both sanctions from me and from the University of Colorado. Further information can be found at http://www.colorado.edu/policies/honor.html & at http://www.colorado.edu/academics/honorcode Sexual Harassment. The University of Colorado Policy on Sexual Harassment applies to all students, staff and faculty. Any student, staff, or faculty member who believes s/he has been sexually harassed should contact the Office of Sexual Harassment (OSH) at 303-492-2127, or the Office of Judicial Affairs at 303-492-5550. Information is available at http://www.colorado.edu/odh. Students with Disabilities. If you qualify for accommodations because of a disability, please submit a letter to me from Disability Services sometime during the first three weeks so that your needs may be addressed. Disability Services determines accommodations based on documented disabilities. Contact: 303-492-8671, Willard 322, or www.Colorado.EDU/disabilityservices Grading Policies and Guidelines Grading Policy: This upper division writing class will hold you to high standards. The grading will be rigorous, but it will also be fair. Although improved critical writing is our goal, we cannot grade exclusively on the category of “improvement shown”—although we can weigh your better papers somewhat more heavily to the extent that it reflects what you have learned. The course syllabus specifies when final drafts are due. As you revise your work in preparation for submission, your instructor will prod, coach, guide, advise, exhort, and encourage. Once you turn in your final draft, your instructor will judge the paper against the same standards that motivated the instructor’s comments during its preparation. If for any reason the instructor is uncertain, he or she may seek a reading from another PWR instructor. Although the instructors may consult with each other about grading, your own instructor is responsible for determining your grade. Should you feel that the grade you receive is unfair, you are always welcome to submit an unmarked original copy of your paper to your instructor, with the request that it be graded by yet another instructor in the PWR. The grade for your paper may be adjusted in light of the comments given by the additional reader. Guidelines: We provide grades based on the final version of the essay you submit. Pluses and minuses attached to grades reflect shades of difference, as do occasional split grades (e.g. A-/B+) A A paper that is excellent in content, form and style: original, substantive, insightful, persuasive, well-organized, and written in a clear, graceful, error-free style. Although not necessarily perfect, it rewards its reader with genuine insight, gracefully expressed. It offers a nuanced claim and compelling evidence. By offering context for its ideas the paper could be read by someone outside of the class. B A clearly written, well-developed, interesting paper that shows above average thought and writing craft. The essay reaches high and meets many, though not all, of its aims. The thinking and writing are solid but may reveal unresolved problems in argument and style, thin spots in content, or some tangents that don’t fit. OR A paper that is far less ambitious than an “A” paper, but reaches all of its aims—a clean, well-organized essay whose reasoning and argument may be somewhat routine or self-evident. C A paper that shows a mixture of strengths and weaknesses. It may be somewhat readable, organized on the surface level, and make a claim, but it will have real unresolved problems in one or more key areas: conception, claim quality, line of reasoning, use of evidence, and language style or grammar. The paper may fill the basic requirements, but say little of genuine significance. OR A competently written essay that is largely descriptive. OR An essay that gives scant intellectual content and little more than personal opinion, even when well written. D The paper is seriously underdeveloped in content, form, style or mechanics. It may be disorganized, illogical, confusing, unfocused. It does not come close to meeting the basic expectations of the assignment. F A paper that is incoherent, disastrously flawed, unacceptably late, plagiarized, or nonexistent. How Science Persuades Semester Schedule for WRTG 3030—Writing on Science & Society Unit One: The Image of Science in Popular Culture Week One Rhetorical Focus: The Image of Science in Popular Culture T 8/24 ASSIGNMENT: Be fully present to offer your unique emotions and ideas to our evolving academic community of WRTG 3030—How Science Persuades. Intro: The Rhetoric of Science: Examples from J. Fahnestock, Michael Berube, etc. Power point cartoon slides as rhetorical representations of science in popular culture. TH 8/26 ASSIGNMENT: Science Worldview Narrative, 1-1.5 pages, to be read aloud in class. In a powerful style to a general audience, write about how would you describe the influence of “Science” in formulating your overall personal worldview? Refer the assignment rubric provided in class and at the wiki: [ petgers3030wiki.wikispaces.com.] ALSO: Read Chandrasekhar’s “Truth & Beauty” and be prepared to discuss whether or not you found any resonance with it. Pathos, Style, and Personal Voice. This could be a model for your own short narrative or not. Community ideas on the Electronic Blackboard. Week Two Rhetorical Focus: The Purpose of Scientific Technologies—Objectivity or Persuasion T 8/31 ASSIGNMENT: View the landmark film Blade Runner over the weekend and type a 2-page Rhetorical Analysis on a thesis relating to some aspect of “science”. Make your thesis as specific as possible. Follow the evidential patterns in the Toulmin handout: 1) CLAIM 2) DATA 3) INTERP. ALSO: Cite a one or two sentence summary of another critic’s views on the film— hopefully pertaining to the influence of science, but not necessarily. Note: If you are having trouble developing an assertion or CLAIM, it might be helpful to switch Toulmin’s pattern to: 1) Data (image or dialogue from the film); 2) interp—a rough ramble about what you think it means; 3) and do the Claim last—as it is hardest. Then flip the claim above to the top to put the Toulmin pattern back in its more convincing evidential place. Some Q’s relating to the film. How does Scientific discovery relate to governance in the film? What is the Asian influence in the film? Is Science linked to a particular business model in the film? (other topics relating to science: Science and humanity; death; love, etc.) TH 9/2 ASSIGNMENT: Read the first 11 tablets of Gilgamesh, (pgs 3-82) the oldest piece of world literature, IN THE TRANSLATION BY DAVID FERRY. In class lecture from John Gage. ALSO: In three typed paragraphs, analyze at least three text examples for the Epic--using Toulmin. 1) CLAIM 2) DATA 3) INTERP to make a convincing argument as to what 3 different text examples mean. If you are having trouble developing an effective CLAIM flip the Toulmin pattern as above. Consider the following questions or ignore them and work from your own interests: 1) How do they view death/immortality as related to a “scientific” worldview? 2) Does technology enter into this view? What is its relation to science? 3) How would the preceding Goddess culture of that region have interpreted the “scientific assumptions” of this text? 4) Other potential science topics: war/dreams/friendship (love?)/etc. Week Three Rhetorical Focus: Academic Thesi and Critical Narrative T 9/7 ASSIGNMENT: Reading from the Website: Jon Marks. “Science, Religion, and Worldview”. Bring in an example of published writing that you think embodies Scientism. Type a one paragraph analysis as to why. See the rubric submitted in class and at the wiki. Note: if potent enough, your choice here could—but doesn’t have to—become the topic for your 5-6 page Rhetorical Essay on the image of Contemporary Science. (DRAFT #1) TH 9/9 ASSIGNMENT: Primary Reading Chapters 1 & 2 from our course text, French’s Science: Key Concepts in Philosophy (pages 1-23). Class discussion concerning the methods of science and their influence in contemporary culture. Why does induction seem to offer greater philosophical problems than deduction? If science achieves results but cannot give completely logical explanations for those results, does it limit scientific ethos for a popular audience? Might this explain why various contemporary audiences call science to question? In class, let’s link this idea to possible artifacts for our Rhetorical Essays: How do scientists make appeals to evolutionary theory? How do AI researchers discuss the possibility of “artificial” human consciousness? ALSO: [Bring in a HYPOTHETICAL typed outline—including thesis and proofs--of a possible example for your Original Rhetorical Essay on some contemporary representation of SCIENCE (excluding Blade Runner and the cartoons discussed in class) (DRAFT #2). Include a typed list of hypothetical artifacts and theories involved. See the separate assignment sheet with its myriad examples. Electric Black Board. Thesis Building Exercise. Structure and organization on the electronic blackboard. We’ll analyze several prior student essays using the critical Rubric. Counterargument as narrative suspense. Week Four Rhetorical Focus: Critics Read & Respond—Theory, Artifact, and Analysis T 9/14 ASSIGNMENT: Reading: chapter 3 in Steven French, (pages 24-42). We’ll discuss how heuristics can create difficulties in validating the actual “methods” of scientific research. Schaberg: Selecting the Cultural Artifact—Original Analysis or Book Report? Please bring 3 or 4 analytical body paragraphs of real artifact analysis from anywhere (hopefully the middle) in your developing rhetorical essay. (DRAFT #3) We’ll work out paper structure and content on the electronic blackboard. In order to convince a skeptical reader of the validity of your ideas, use the following pattern: CLAIM 2) DATA 3) INTERPRETATION. Your CLAIM will make a clear assertion about the meaning of the cultural artifact under investigation; your DATA is the actual evidence in the form of text, image, music, dance, building, etc.; the INTERP (or WARRANT) will make the necessary connections for a reader who does not have the pleasure of attending our class. We’ll share your writing in both large and small groups. We’ll also model a prior student’s essay. Electric Blackboard. Make sure you are doing analysis of real Scientific cultural representations. They must be tangible—not abstract. [Although everyone is expected to write 3-4 pages of the rhetorical essay by next Tuesday, we need 3 NEW volunteers to send out at least 3 pages of their developing rhetorical essay 24 hrs. in advance of Thursday’s class.]] TH 9/16 ASSIGNMENT: (DRAFT #4): Large group workshops of the three student drafts. We’ll work out paper structure and content on the electric blackboard. Note: everyone is expected to be at the stage of 4 polished pages—not just the volunteers! Modeling effective critical reading and on-line commentary. Have copies of the drafts available in class with your annotations either by hand or in “track changes”. Comments should be specific and intended to help these writers improve their essays and to help me see how your skills as a writing critic are progressing. See the Critical Rubric. Week Five Rhetorical Focus: Intros, Conclusions and Counterargument as Persuasive Tropes T 9/21 ASSIGNMENT: Please bring 2 copies of your FULL draft of the 5-6 page Rhetorical Essay on the image of science in contemporary cultural. I will be checking to see that everyone has a full draft. Small group workshops using the critical rubric. (DRAFT #5.) Unit Two: Big Science and Big Bucks (Taking your Science Proposal to the Bank) TH 9/23 ASSIGNMENT: DUE IN CLASS: Final draft of 5-6 page rhetorical essay, (both hard and electronic--which I will submit to turn-it-in.com) and your 1-page peer review. No late papers can be accepted. (DRAFT #6). In class reading: “Why Academics have a hard Time Writing Good Grant Proposals” Mock/Real Proposal Assignment: In transitioning from the Rhetorical Essay to a Grant Proposal, we will shift our sense of audience expectations in several significant ways. Although at first glance it may appear that the audience is purely scientific, we’ll soon see that this is far from the case. Funders have many different points of view in regarding potential recipients. In working through a number of proposal genres we will put ourselves in an excellent position to understand the myriad ways that science writers must adapt in order to fund their most important research. For this section you will be asked to: 1) Decide on an original hypothesis that you think needs testing (or a problem for which you have a solution.) 2) Locate at least a hypothetical funding source 3) Draft a letter of inquiry—to be okay’d by me before you go on to the next step 4) Write your full draft of the proposal 5) Submit your proposal to me and—I you wish—to the authentic funding agency you have targeted. Your proposal must have these SIX sections, each with a separate heading: Introduction; Background; Methods; Time Schedule; Budget; References. Please add an Appendices section if needed. Note: Since you may well decide to complete and write up this research for the final 10-15 page Academic Journal Article, you may want to select a proposal question that you can actually resolve in the next 10 weeks. We’ll present several prior-student model proposals in class. Small group brainstorming (DRAFT #1) Week Six Rhetorical Focus: Proposals—Arguments at the Borderlands of Science and Business T 9/28 ASSIGNMENT: On line reading from Goldbort’s “Scientific Grant Proposals” Be prepared for class discussion with any questions you may have about your project For Class: Bring a paragraph outline of two possible proposal topics that may serve as your letter of inquiry. For class: Answer Goldbort’s questions in detailed writing—they constitute a legitimate draft of your proposal: What is the project’s Goal? Is the Project Worthwhile? What is the Ethos of the grant writer? Has secondary literature been adequately researched? Has the projects timetable been realistically considered? Is the requested funding truly essential to finishing the project? (DRAFT #2) TH 9/30 ASSIGNMENT: On line reading from Friedland and Foit’s, “Writing Successful Science proposals.” Be prepared for class discussion with any questions you may have about your project. Proposal Letter of Inquiry Due in class. This short 1-2 page formal document should define the problem, state the solution, the ethos of you, the researcher, to solve the problem, and the funds needed to do so. Note: this assignment serves as the threshold through which you must past to continue onto the drafting stage of your proposal. (DRAFT #3) Week Seven Rhetorical Focus: Proposal Audiences—Anticipating the Counterargument T 10/5 ASSIGNMENT: (DRAFT #4) Please bring in an electronic copy of your draft of the Introduction, Background, & Methods sections of your Mock/Real Science proposal. I will be checking to see that everyone has a substantial draft. Small group workshops using the critical rubric. (DRAFT #4.) Also for class: find a sample proposal on line (not from the UROP) and present it very briefly to the class. (DRAFT #5) Small group workshops. In class writing for the proposal. TH 10/7 ASSIGNMENT: Large group workshops of the three student Proposal drafts. We’ll work out proposal structure and content on the electric blackboard. Note: everyone is expected to be nearing the full draft stage—not just the volunteers! In class we’ll model effective critical reading and on-line commentary. Have copies of the drafts (either electronic or paper) available in class with your annotations either by hand or in “track changes”. Comments should be specific and intended to help these writers improve their Proposals and to help me see how your skills as a writing critic are progressing. See the Critical Rubric. (Draft 6) Also for class discussion: On line Reading from Beer’s “Writing as an Engineer” Week Eight Rhetorical Focus: Proposals—Sections and Paragraphs as Organizing Frameworks T 10/12 ASSIGNMENT: Large group workshops of the three student Proposal drafts. We’ll work out proposal structure and content on the electric blackboard. Note: everyone is expected to be nearing the full draft stage—not just the volunteers! In class we’ll model effective critical reading and on-line commentary. Have copies of the drafts (either electronic or paper) available in class with your annotations either by hand or in “track changes”. Comments should be specific and intended to help these writers improve their Proposals and to help me see how your skills as a writing critic are progressing. See the Critical Rubric. TH 10/14 ASSIGNMENT: Please bring in an electronic copy of your FULL draft of Mock/Real Science Proposal. I will be checking to see that everyone has a full draft. Small group workshops using the critical rubric. (DRAFT #7.) Unit Three: Writing for Scientists in the Discipline (Attempting Original Research in your Discipline) Week Nine Rhetorical Focus: Logos and the Scientific Audience T 10/19 ASSIGNMENT: Mock/Real Proposal Due in class. Your proposal must have these SIX sections, each with a separate heading: Introduction; Background; Methods; Time Schedule; Budget; References. Please add an Appendices section if needed. Include the funding agency’s name if you are sending it off. Introduction to the 10-15 page Science Research Article—Due December 9th. In transitioning from the Rhetorical Essay to the grant proposal, we shifted our sense of audience expectations in some significant ways. Funders, as we learned, have their ear cocked halfway toward the NARRATIVE of scientific possibilities, not just toward the science itself. As we shift yet again towards a more discipline-specific audience we will still continue to extend our understanding of how audience and genre influence scientific writing practice, within the standard journal article. Some writers will want to continue with the proposal project—bringing it to full fruition, even if it has been significantly altered during the draft process. Others may want to start afresh. Whatever the case, the paper must present ORIGINAL evidence for an Original research question. See below and the separate assignment sheet for details. Please use the following format or something like it. 1) INTRODUCTION: The Introductory section defines the subject, describing characteristics of your study and their importance. It elucidate the controversy or question which arises and states how your experiment or research addresses this question. Be sure to relate this section to the contemporary literature. 2) MATERIALS AND METHODS: The Materials and Methods section describes the essential stages of procedure necessary to reproduce your research. Discuss sourcing, experimental design, and procedures used for measurement. 3) RESULTS: The Results section reports, without conclusions or discussion, specify effects the Materials and Methods to specify general trends in your results. Each type of result takes a separate paragraph. Use tables or graphs which are easier to understand. 4) DISCUSSION: The Discussion section explains what the results show and interprets what they mean. Try to match each paragraph in Results with a paragraph in Discussion. TH 10/21 ASSIGNMENT: On line reading from: Goldbort. Also bring in at least 2 examples of possible original research projects that you could work on over the next 7 weeks. We’ll sort through your ideas for potential on this topic. We’ll also look at sample papers from the AAAS website and ScienceDirect to generate an understanding of genre differences in different academic domains. Week Ten Rhetorical Focus: Reason and the Rhetoric of Disciplinary Ethos T 10/26 ASSIGNMENT: Come prepared with 2 page INTRODUCTION on the topic of your choice—either carrying on from the proposal project or commencing anew. [Draft #2] On line Reading: Gopen and Swan’s, “The Science of Scientific Writing.” TH 10/28 ASSIGNMENT: Bring in a draft of your MATERIALS AND METHODS section: [Draft #3] We’ll review these in small groups and compare them to prominent articles from “Nature” “Science” and the AAAS website. Content comprehension and rhetorical knowledge. Week Eleven Rhetorical Focus: Citation, Ethos, and Academic Research T 11/2 ASSIGNMENT: Bring in a draft of your RESULTS section: [Draft #4] We’ll review these in small groups and compare them to prominent articles from “Nature,” “Science,” and the AAAS website. TH 11/4 CLASS IS OPTIONAL. DUE TO A DAY-LONG SERVICE LEARNING WORKSHOP, I WILL NOT BE PRESENT IN CLASS—BUT THAT IS NO REASON WE COULD NOT HAVE A VERY PRODUCTIVE CLASS. Bring in a draft of your DISCUSSION: [Draft #5] We’ll review these in small groups and compare them to prominent articles from “Nature” “Science” and the AAAS website. We need 3 NEW volunteers to send out to the class roster their developing paper 24 hrs. in advance of next Tuesday’s class. Week Twelve Rhetorical Focus: Criticism and Empathy—Framing Feedback as Learning T 11/9 ASSIGNMENT: DRAFT #4: Large group workshops of the three student drafts. We need 3 NEW volunteers to send out to the class roster a draft of their developing paper 24 hrs. in advance of Thursday’s class. We’ll work out paper structure and content on the electric blackboard. Note: everyone is expected to be at the Full Draft stage—not just the volunteers! Modeling effective critical reading and on-line commentary. Have copies of the drafts available in class with your annotations either by hand or in “track changes”. Comments should be specific and intended to help these writers improve their essays and to help me see how your skills as a writing critic are progressing. See the Critical Rubric. T H 11/11 ASSIGNMENT: Large group workshops of the three student drafts. We’ll work out paper structure and content on the electric blackboard. Note: everyone is expected to be at the Full Draft stage—not just the volunteers! Modeling effective critical reading and on-line commentary. Have copies of the drafts available in class with your annotations either by hand or in “track changes”. Comments should be specific and intended to help these writers improve their essays and to help me see how your skills as a writing critic are progressing. See the Critical Rubric. Week Thirteen Rhetorical Focus: Powerpoint and Prezi—Evidence and the Visual Image T 11/16 ASSIGNMENT: In class drafting with powerpoint and/or Prezi. Small group work shops regarding images as argument. On line reading “Powerpoint as Persuasion.” Draft 5. It’s important that we see these oral presentations AS PART OF THE DRAFTING PROCESS. True, they are graded (5%) but the oral presentation and following criticism should give some excellent ways to improve your research paper before the deadline. TH 11/18 ASSIGNMENT: GROUP 1 Powerpoint or Prezi Mock Conference Presentations of your Scientific Research papers. We’ll be looking for the intersection of a fine research thesis, convincing sections, consistent use of evidence Claim/data/Interp and the full use of the visual imagery that projected media such as powerpoint and Prezi make available. Use feedback gained from your oral presentation to further your draft process. No book reports please! No summary of what a secondary source says! The point here is to mimic the difficulty you are confronted with in your research essays and if necessary to use a theories to clarify the meaning of the thesis in question. DRAFT #6 Fall Break—No Class Week Fourteen Rhetorical Focus: Powerpoint and Prezi, Scientific Presentation or Entertainment? T 11/30 ASSIGNMENT: GROUP 2 Powerpoint or Prezi Mock Conference Presentations of your Scientific Research papers. We’ll be looking for the intersection of a fine research thesis, convincing sections, consistent use of evidence Claim/data/Interp and the full use of the visual imagery that projected media such as powerpoint and Prezi make available. Use feedback gained from your oral presentation to further your draft process. No book reports please! No summary of what a secondary source says! The point here is to mimic the difficulty you are confronted with in your research essays and if necessary to use a theories to clarify the meaning of the thesis in question. DRAFT #6 TH 12/2 ASSIGNMENT: Group 3 Powerpoint or Prezi Mock Conference Presentations of your Scientific Research papers. We’ll be looking for the intersection of a fine research thesis, convincing sections, consistent use of evidence Claim/data/Interp and the full use of the visual imagery that projected media such as Powerpoint and Prezi make available. Use feedback gained from your oral presentation to further your draft process. No book reports please! No summary of what a secondary source says! The point here is to mimic the difficulty you are confronted with in your research essays and if necessary to use a theories to clarify the meaning of the thesis in question. DRAFT #6 Week Fifteen Rhetorical Focus: Wrapping it Up—Intros and Conclusion and Counterarguments T 12/7 ASSIGNMENT: Electronic copy of full 10-15 page scientific research article for final feedback in small group workshops. I will check to see that everyone has a full draft. DRAFT #7. Please bring your laptops. Readings: Schaberg--“Counterargument as Narrative Climax” TH 12/9 ASSIGNMENT: DUE IN CLASS: Final draft of 10-15 page Scientific Research article, (both hard and electronic--which I will submit to turn-it-in.com) and your 1-page peer review. No late papers can be accepted. Due by Wednesday December 15th: Professional Writing Expectations Statement (5%). Shifting toward a more disciplinary perspective, students will complete interviews with specialists in their particular field, and generate a 3-4 page in which they elucidate the writing forms and practices that will be expected of them upon entering their field. Thanks for a great semester! Good luck in all future endeavors.