science fair tips

advertisement

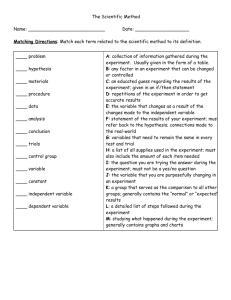

SCIENCE FAIR PROJECTS Tips for a Successful Project How to Identify a Good Topic Topic has to be narrow, specific. Topic must be realistic, practical (do you have access to the equipment, etc.). Topic must survive constraints from rules and regulations. Topic must match your interests! Types of Projects Models Most have limited creativity! An example of a creative model would be a design for a more efficient airplane that would include experiments supporting the theory behind the model design. Types of Projects Surveys Be aware of rules! Before drawing conclusions use math (statistics) to analyze your results. Use data tables and/or graphs over a period of time in order to use extrapolation. Type of Projects A repeat from the past An example would be an illustration of a scientific law. This type of project might lack creativity! Look for an original application rather than a repeat. View things from a different angle! For example: write a computer program to simulate Mendel’s genetics. Types of Projects Original Investigation This is the most difficult to plan or conduct! It requires more library research, more critical thinking and lab work, but is also the closest to a scientific approach. Planning For Your Project Document what you read Use index cards in a library search! For Books: Record author’s name, title, publisher, date of publication For Magazines: Record author’s name, title, journal name, publisher, volume number, and page number(s). For an Internet Source: Record author and URL. Example of a Scientific Bibliography Magazines Young, M., “Pinhole Optics,” Applied Optics,10, 2763 (1971). Fitch, J. M., ”The control of Luminous environment” Scientific American, 219, 190 (Sep .1968). Prigo, Robert, Bachman, C.H., “some observations on the process of walking,” Physics teacher.14. 360 (1976). Example of a Scientific Bibliography Books Goldstein, Herbert, Classical Mechanics, Addisson-Wesley, Reading, MA (1950), p.308. Uvarov, Boris, Grasshoppers and locusts: a handbook of general acridology, Cambridge University Press, London vol.1 (1977) p.479. Plan Your Equipment Be realistic! Cut down on expenses. If you can construct some of your own equipment to gather data, this is a plus because you demonstrate creativity. You may make the measurements at school by making arrangements with a teacher. Plan for Safety Avoid disease causing organisms, explosive gases, and/or dangerous chemicals! If your project presents any safety concerns, make certain to work under the supervision of a qualified scientist. Always share your project with your science sponsor at school! He or she will inform you about safety or refer you to someone who can advise you. Plan Your Time Keep a book where you will record your data and an agenda, list of supplies, bibliography, etc. Plan your time for each part of your project. Set a realistic timeline, as well as a deadline. This will train you in learning responsibility and organization. The Scientific Method All science fairs (and all of science-hence the name!) follow these simple steps. Don’t get overwhelmed, it is a way to organize your thinking. It’s logic, not an exam. 1.Observations - this is what you learn from your research and experience about what you are interested in 2. Hypothesis – a question that you form based on your observations that you want to test to prove or disprove 4.Test the Experiment – Use your design and see what happens. Make sure to take good notes of what you do and what happened 3. Design an Experiment – think of how you want to test the hypothesis, gather the materials you need, and think of the steps you need to take. 5.Accept or reject results – These are your conclusions based on your experiment combined with your research Then… 6. Go back and make a new hypothesis based on these conclusions Scientific Method Hypothesis (Your Purpose) Should be one, clear and brief sentence based on the information gathered during research. The hypothesis is followed by a brief statement explaining or justifying this purpose. Do not consider your experiment or project a failure if your investigation does not confirm your hypothesis. Just say that your hypothesis is not verified in your conclusion. The important point is to arrive at the truth. You may suggest further research or include a second phase in your project if the time permits. Forming a hypothesis or stating the purpose Hypothesis: A trial solution to a research problem. The data you acquire through experimentation can be used to support or refute the hypothesis. It does not matter if you prove it is right or wrong, so long as you stick to the topic. Sample Hypotheses - The ingestion of caffeine increases the heart rate of Daphnia sp. - Hard materials are more effective at reducing sound levels than soft materials. Tips! Be specific in stating your hypothesis or purpose, but don’t be overly wordy Think 2 sentences maximum. If you need more space to describe the problem, you’re making it too complicated, simplify! Your Experiment Outline steps: keep design as simple as possible (the more complicated, the greater the chance of error). Types 1) qualitative: careful observations without getting involved in measurement or statistical analysis. 2) quantitative: measurements and collection of numerical data (use the metric system); best type of data because it permits you to use mathematics to establish relations; not based on opinions, but facts. The Control Experiment You will need to include a control set-up as well as an experimental set-up in your experimental design. The control and experimental set-ups are exactly the same except that the control set-up does not contain the independent variable (the thing that you have changed for your experiment). Example: Hypothesis: Plants grow better in green light than in regular light. Experimental set-up: Plants grown in green light and watered and fertilized in the same way as plants grown in regular light (the control). All other variables, such as type of soil, the amount of humidity, the air temperature, and the light exposure are kept the same for both the experimental set-up and the control set-up Don’t forget to Rinse and Repeat! The more times you repeat an experiment and obtain the same results, the more statistically valid your results are. Doing Your Experiment Include a control: vary the experimental conditions; if the outcome is caused by another factor, this will allow you to single out the results. Keep accurate and regular records. Objectivity: Do not discard a result that is not in agreement with the rest of the study. Lone results may be due to faulty or contaminated samples, math errors, or give a clue to some interesting discovery. Analyzing Errors Ask yourself these questions: - What were the limitations of your experiment? How were extraneous variables minimized? What went wrong? What went right? How might you improve your experimental design in future studies? Write up answers to these questions in your report along with the rest of your data. Results Keep a notebook for recording any information, observations and data (in tables, graphs, etc.). Do not use scrap paper - use photographs, drawings, diagrams, etc. You must never commit results to memory. Looking for trends and forming a conclusion - Did you collect enough data? - Which variables are important? - How do your results compare with other studies? - Do your results seem reasonable? - Are there any trends in your quantitative/qualitative data? - Do your results support your hypothesis? If not, why not? Has your experiment tested your hypothesis? Remember to keep an open mind about your findings. Never change or alter your results to coincide with what you think is accurate or with a suggested theory. Sometimes the greatest knowledge is discovered through so-called mistakes. Your Conclusion Must come directly and solely from the data in your notebook. If you cannot arrive at any conclusion from your data, find a different approach to your experiment. Must be clear and concise. Do not hesitate to present all the conclusions your data can support (especially if your project has several phases). Do not reach a conclusion that is not supported by your data! The conclusion should suggest a direction for further study. Writing the research paper Your report will provide interested readers with a comprehensive look at your topic and research. Your paper should include information collected during the research as well as a complete description of your experiment, data, and conclusion. A good research paper Should be written in the past tense and have the following components: -Title and/or Title Page -Abstract, Summary Page/Index -Introduction, including Literature Review -Hypothesis or Statement of Purpose -Materials and Experimental Methods -Data and/or Results -Discussion and Analysis of Data or Results -Conclusions -Acknowledgements -Bibliography Also, it is helpful to make a summary of your report with bullet points so your judges can quickly and easily see your main points. What To Include In Your Report A Title Do not be vague. Include both the dependent and independent variables in your title. In an engineering project, the title might be the name of your design or your design versus its performance in a given environment. Writing the Abstract Once you’re done with the experimentation, it is time to summarize! The abstract is the last part of the project report to be prepared, and it is written after the project is completed. An abstract is a short summary of your project that informs the reader what the project covered, and what has been accomplished. An abstract should include: - A statement of purpose or a hypothesis. - The experimental design, descriptive outline of the procedures or methods. - A summary of results. - Your conclusion. - Application of the research project, if you have space, and your ideas for future studies. In total, the abstract should be a paragraph, not a page The Abstract The abstract is the summary of your scientific report. Make certain that you write the abstract only after you write the report so you may stick to the essentials. State Your Purpose Be brief! You want to familiarize the reader with the problem you are intending to solve. Explain what impact your investigation may have on scientific or technical knowledge. Explain Your Methods This is your procedure. The materials you use. This is the step-by-step investigation. Follow-Up With Results These are your observations. Your observations will be recorded in sentences and paragraphs. Be clear concise simple and accurate. You may use photos or schematic illustrations. Record in tables and/or graphs. Graphs take a primordial place in the way the scientific community communicates information . They are almost always included in any scientific report. Organization of Data in a Table The independent variable is written in the first column. For example: when you walk, the distance you walk is changing as a function of time (D = f (t). Time is the independent variable and distance is the dependent variable. The time data will be in the first column and the distance data in the second column. Note: As shown in the next slide, if an SI unit is named after a person, it has to be capitalized. The unit of current is named after the scientist Ampere and the unit of potential is named after the scientist Volta. The equation is V = R (I). The amount of volts depend on the amount of current. Example of a Data Table Note: the independent variable is placed in the first column. Current (Amperes) Potential (Volts) 0.12 1.2001 0.14 1.3358 0.18 1.7871 0.20 2.0004 0.25 2.4715 Example of a Graph Growth rate of Beans Plant 9 8 y = 0.4734x + 0.7195 R2 = 0.994 7 Growth (cm) 6 5 4 3 2 y = 0.2264x + 0.0629 R2 = 0.9966 1 0 0 2 4 6 8 10 Time (days) Roots (cm) Stem (cm) 12 14 16 Example of a Graph % Light at Pecan Island on Dec 21 2000 and on June 21 2002 100 % Light (Relative Scale) 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 5 10 15 Time 21 (hr) % light on December 20 25 % light on June 21 30 Analyze Your Results Establish relationships or proportionality factors. Determine how data are mathematically related. The variables are directly proportional (straight line: y = mx +b). The variable are inversely proportional (hyperbola: y = k/x). The variables vary as a square function (parabola: y = ax2 + bx+ c). Conclude Your Report Use your analysis to establish conclusive statements. The conclusion should always include suggestions for further research to solve the problem or look at it from a different angle. (What new problems or questions were uncovered by the project?) Include Your References This is your bibliography Your Board Display The Exhibit Size is Limited! 76 cm (30 inches) deep, front to back. 122cm (48 inches) wide, side to side. 274 cm (108 inches) high, floor to top. Projects exceeding these dimensions are automatically disqualified! Presenting Your Project Introduce yourself. Give the title of your project. Explain your purpose. Summarize any background information. Discuss briefly how you developed an interest in the topic. Explain how you proceeded. Use your display to support your explanations. Preparing your project board & visual display The following items are part of the project board: - Title - Introduction or Background - Problem or Purpose - Hypothesis - Procedure or Experimental Design - Materials Used - Results (Data, charts, diagrams, etc.) - Analysis - Conclusions - Applications - Future Applications or Future Research Rules of thumb: Your project title and section headings on your board should be large enough to be easily read from 6 feet away. The regular text displayed on your board should be readable from a distance of 3 feet. Make it easy for the judges and others to assess what you have done: if they don’t understand it, they cannot tell if your work was great or not. Example of Board Layout http://school.discoveryeducation.com/sciencefaircentral/Science-FairPresentations/How-to-Create-a-Winning-Science-Fair-Display-Board.html Citing Sources: Avoiding Plagiarism in Scientific Work When using the work of other scientists, you must document their contributions by citing your sources of information. Scientists use the American Psychological Association (A.P.A.) For more details you may want to consult “A Writer’s Reference” by Diana Hacker, or Purdue University’s APA Style Guide http://owl.english.purdue.edu/ In text example: Internet source: Author, date, and state “Internet” (Martin and Stephen, 2000, Internet) OR (Compost and Worms, 1952, Internet) Examples of Displays Examples of Displays Examples of Displays Examples of Displays Oral Presentation Below are some key points to a good presentation - Be positive and confident of your work. You have worked hard and know your project better than anyone else. - Practicing ahead of time in front of a mirror, family members and friends, - Try not to read from a script. - Dress appropriately and neatly. - Keep eye contact with your listeners during your presentation. - Use your board/poster as a prop and tool to help you present you work. - Present your work enthusiastically. Judge’s Pet Peeve: Judges will ask you questions. If they ask you something you don’t know, tell them you don’t know. Don’t try to make something up on the spot. It’s ok if you don’t know. It’s not ok if you make up things you never read! Presenting your Project Emphasize results and conclusions. Point to your exhibit to support your logic. This will help as you present your project logically and sequentially. Tell about applications or suggestions for further study or suggestions to improve your project. Invite questions from the judges. Additional Tips Practice makes perfect!!!!! Practice in front of friends, teachers, parents. Do not antagonize the judges! Do not chew gum, wear extravagant clothing, etc. People are impressed with good manners! Additional Tips Do not stand between the exhibit and the judges, but on the side. Give them a copy of your abstract, peak their interest, and maintain interest by periodic eye contact. Point to lab apparatus, charts, and photographs on display. This will allow you to describe your project in an appropriate sequence. Do not read directly from your project. You should know what you are talking about! This is your project! Judging Criteria Scientific Content and Application Does the project have a clear hypothesis? Is the problem specific and well stated? Are all variables recognized and defined? If a control was necessary, was it included? Is the data sufficient and relevant? How do you communicate scientific thought? Do you use scientific language, tables ,charts, and/or graphs? Is your analysis based upon mathematical relationships? How did you arrive at your conclusions? Did it include ideas for further research? Does it contain a bibliography? Judging Criteria Creativity and Originality Did you construct a piece of equipment? How did you get the idea for your project? Judging Criteria Thoroughness Are your conclusions based on a single experiment or do you have enough repetitions to obtain sufficient data? Did you look at all possible approaches? For more science fair information Websites: Massachusetts State Science and Engineering Fair www.scifair.com The MSSEF Student Guide: "How To Do A Science Fair Project” is posted here. Additional resources for science fair information are listed on the MSSEF website. Science Buddies www.sciencebuddies.org/ Dr. Shawn’s Science Fair Projects www.scifair.org Reference Books: Bochinski, Julia. 1996. The Complete Handbook of Science Fair Projects. John Wiley and Sons. New York. Brisk, Marion. 1994. 1001 Ideas for Science Projects. Simon and Schuster. New York.