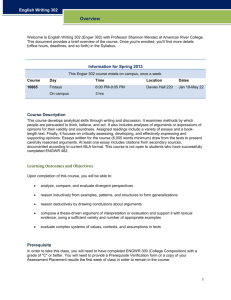

HST 380 Syllabus

advertisement

History 380: U.S. Environmental Politics Since 1900 Course Meetings: T R F 10:00-10:50 CCC 224 Office Hours: T R 12-2pm 473 CCC UWSP – History Department Dr. Neil Prendergast nprender@uwsp.edu Not too long ago, an environmental activist from New Mexico declared that “Smokey Bear is a white racist pig.” Smokey Bear? When I was a kid, I learned that Smokey Bear helped save forests from burning down. I even saved a dollar from my allowance to get into some kind of Smokey Bear club, a membership that came with a patch that gave me great pride. I was helping nature. I was doing a good thing. The world, of course, is not as simple as the way I perceived it when I sent away for my patch. Smokey Bear came to be in 1944, when the Forest Service decided it needed an educational campaign to convince Americans that they should do all they could to prevent forest fires. As the slogan went, Only you can prevent forest fires! Clearly, though, not every American has agreed. In New Mexico, there has long been conflict over whether or not fires were good or bad for the forest. For millennia, fire had been a useful tool that Native people used to regenerate deer habitat. In the early 1900s, the Forest Service attempted to stamp out every fire on national forest land. However, in New Mexico, many small farmers (many of whom were Native or Hispanic) saw this policy as one more way the federal government attempted to control land use, much to the detriment of traditional hunting. So why did one New Mexican activist declare Smokey Bear was a “white racist pig?” Even a brief understanding of the state’s history shows that land management decisions are wrapped up in the history of one group’s power over another. The quote also strongly suggests that race and other social issues play important roles in environmental politics. Clearly, I had no idea how controversial Smokey Bear was when I was eight years old. This semester, our goal is to understand why Americans fight about nature. While we won’t focus on Smokey Bear, we will look closely at a series of important case studies in the history of American environmentalism. It’s important to make a critical distinction here, by the way. This class is not an indoctrination into environmentalism. It’s a careful study of how conflict occurs when Americans wrest a living from nature. In each case study, we’ll ask the same question, our guiding question for the semester: Why do Americans fight about nature? As we turn this question over in case study after case study, you will begin to think deeply about the nature of conflict. Cultural assumptions, the use of science, property rights, and much else will come under our magnifying glass. By the end of the semester, you’ll be able to look at an environmental conflict, sort out the arguments, and evaluate what’s at stake. No matter where you fall on the political spectrum, this is an important skill. Enduring Understandings: Conflicts over nature have cultural, political, economic, and ecological causes. Environmentalism has had a varied membership and an assortment of goals in American history. Learning Outcomes: After taking this course, students will be able to: describe the history of the environmental movement, including its major events and classic texts. evaluate arguments in an environmental conflict. explain how environmental conflicts happen. identify the ways the past shapes a current environmental conflict. Course Structure: Since our goal is to understand conflict, I designed our tasks to make us better and better at that. Take a quick look at any of our units. Each one has a guiding question. To answer these questions, each unit has us traveling a path. Note how the units tend to begin with a lecture, move to a set of primary sources to be discussed in small groups, then turn to a secondary source to focus a classwide discussion, transition into a paper workshop, and then finish with another classwide discussion, this time about your papers. This pattern orients us with a big picture, lets us dive into the nitty gritty of a conflict, assess the argument of someone examining the whole conflict, and forces us to evaluate the conflict ourselves, using writing and discussion as our tools. Examining conflict this way moves us from merely remembering facts to evaluating why people fight about nature. Completing this pattern again and again, unit after unit, makes this high-order thinking second nature. History as Laboratory: You might reasonably wonder why we should use history to understand the nature of conflict. After all, there seems to be plenty of conflict happening today that we could study. (In fact, we’ll end the course with a present-day debate: mining Wisconsin sand to use in hydraulic fracturing.) There are at least three good reasons. First, we tend to have less at stake in past events, which makes a critical distance more possible, at least in some occasions. Second, since historical events are referenced routinely by people engaged in environmental affairs today, understanding key conflicts from the past will help you speak the language today. Third, the actual outcomes of historical events created the political, legal, cultural, and ecological terrain we live in today, so studying them will let you know why present-day debates have the shape they have. Office Hours: You are welcome to visit me in my office. I set aside office hours so that I have the chance to talk with students one-on-one. During that time (TR 12-2pm 473 CCC), I do not have any other commitments. My only commitment is to speak with my students. To visit me during office hours you do not need an appointment. We can chat about anything going on in the course, from content to class dynamics. They are an especially good time to check in if you missed class. (Office hours are not in any way, shape, or form akin to a visit to the principal’s office in high school!) If you have class or work during my office hours, I am happy to make an appointment so that we can still speak. Just email me. Readings: We're taking an interesting approach this semester, in terms of the readings. We're focusing the first three units on a major book from the period. By giving close attention to long selections from Aldo Leopold's A Sand County Almanac, Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, and John McPhee's Encounters with the Archdruid, you will walk away from this course able to discuss key works in American environmentalism. (These are available for purchase at the university bookstore.) To truly understand these books, we need to understand their historical moment. What were the authors responding to? Why did they pick particular strategies to appeal to readers in 1954, 1962, or 1975? How did the public receive the authors' messages, then and in later years? To even begin answering these questions, we need a basic history of the environmental movement. For that we're reading a good, straightforward book called First Along the River. I think you'll like this one because it lays out the key events of the environmental movement clearly and in short chapters. (This book is text rental.) Along the way, we will also read some academic articles, although not usually more than one a week. I try to pick the most readable of these. They're a good addition to our inquiry because they offer serious depth on important topics--from the public reaction to Silent Spring to the importance of evangelical Christianity to environmental activism. Academic articles are also excellent for modeling how to make an argument as well as possible, so we will use them for our goal of making crafty arguments. (These readings will be available via D2L.) When we do take that close look at a topic, we will also look at sources from that particular time, written by people actually involved in an historic conflict. Expect to read these primary sources every week. On occasion, I will not give you pdf’s of primary sources, but will give you a list of websites to locate sources useful to our discussion. (Primary source pdf’s and links will be on D2L, too.) Finally, we have one last reading: a new book called Living Through the End of Nature. We'll read long selections from this one after Thanksgiving. It briefly examines the environmental movement's history (we can see if his history is as good as the one we put together in the classroom during the semester!), but really focuses on how environmentalism can change its way of framing problems, so that it can become more successful in achieving its goals. We do not have to be rooting for environmentalism to make this book worthwhile or interesting. Coming at the end of a semester inquiry, it's useful to us as a statement about where environmentalism is now. If we understand the author's discussion, then we've made ourselves conversant in the twentieth-century public discussion about Americans and nature. If we can argue with him a bit, then we've started to develop our own ideas about the history of environmental politics. Place at the end of the semester, therefore, this book will be very satisfying...and generate some good class discussion. (This is also available for purchase at the university bookstore.) These readings probably sound like a lot of work. On the one hand, they are. This class is an upper-level course in a reading intensive discipline. On top of that, we have some important, complicated things to understand, which simply takes some reading to accomplish. On the other hand, all of these readings are spread out over 15 weeks. Most weeks we will read about 60-80 pages. Sometimes we will divide up readings across the class to help break up the books. Other times, we will split the class into different reading groups for the academic articles--which is a nice way to spark discussion, not just make the reading load reasonable. Finally, I have taken special care to select works that are as readable as possible. All in all, if you take a serious approach to the reading, you will find it worthwhile and not unreasonably taxing on your schedule. Grading: 60 points for Papers [six at ten points each] + 20 points for Discussion Posts [ten at two points each] + 20 points for Teamwork. Letter grades for the semester follow the typical pattern: A 93-100 B+ 87-89 C+ 77-79 D+ 67-69 A- 90-92 B 83-86 C D B- 80-82 C- 70-72 73-76 F 59 and below 60-66 Papers: As you will see on the schedule, papers are due on Thursday evenings at 9pm on D2L. (You must also bring a hard copy to class the next day.) You will notice, too, that the day after a paper is due, the readings for that day’s class meeting are “Student Essays.” That’s right: you will be reading each other’s work. For each of these occasions, you must read five of your colleagues’ essays. The reason for this requirement is simple. Writing is communicating and you need a group of people to communicate with to make your writing worthwhile. Furthermore, in this upper-level course, discussion is a primary way for us to learn. Discussion, of course, is the sharing of ideas. Allowing other students to read your written work is simply an element of discussion—one, in fact, that lets you form your ideas with more time and reflection than classroom conversation typically allows. I think you will see that as the semester develops, this sharing of papers will lead to better, more meaningful, and more enjoyable classroom discussions. I realize that for some folks the act of sharing written work is terrifying. If that sounds like you, I’m going to ask you to take a leap of faith and trust in the decency of your classmates to treat every class members’ thoughts with respect. In my short time in Wisconsin, I have found such decency to be the norm. I also take it as my responsibility in the classroom to foster a learning culture in which ideas flow freely, without fear of disrespect. For each unit, I will make available a full paper description complete with rubric, but just so you can see what lies ahead, here are the questions for each paper: Conservation Paper: Why did Americans disagree about conservation? Rise of Environmentalism Paper: Why was Silent Spring controversial when it was published in 1962? Environmentalism Established Paper: How did ‘participatory democracy’ change environmental debates? Challenge to Environmentalism Paper: Why did environmentalism become a partisan issue in the 1980s? Evaluating the Sand Mining Debate Paper: On what basis do the parties in conflict disagree? Lasting Questions Paper: What questions from the history of environmentalism are most important? Discussion Posts: Please note that the deadline for these posts is 9pm and that your colleagues’ posts are required reading for the next day’s class meeting. I chose 9pm as a deadline as a compromise for two reasons: 1) on the one hand, it gives a good deal of time to complete the reading and reflect enough to write a short, though thoughtful response to the discussion prompt; 2) on the other hand, it still leaves time for us to read each other’s responses before retiring for the evening or in the morning. After the first few weeks, we’ll discuss the 9pm deadline as a group. Teamwork: Everyone in this class has been on a team before, whether an athletic team or a board game team. Teams work well when they pull their members together to achieve a common goal. Often, they foster greater individual accomplishment than what one could achieve on his or her own. This effect is called synergy. Since we all want to do well in this class, let’s create some synergy for ourselves by thinking of our small, discussion-oriented class as a team. Listening to each other, asking thoughtful questions of each other, and offering basic respect are obvious ways to become an intellectual team. I encourage you to pursue them! But being prepared in all the normal ways is also an important part of becoming a team. Showing up to class with the readings finished, posting thoughtful discussion comments, and creating your own questions and opinions are all individual efforts that show others you care and that they should care, too. (The unfortunate flip side is that when you show up unprepared, the prepared students feel as though they’ve wasted their time. They start to prepare less and the bar in the class lowers and lowers until class meetings are just not challenging, fun, or interesting anymore.) Twice in the semester I will ask you to rate your own teamwork. You’ll fill out a brief questionnaire and submit it to D2L. I will use these questionnaires when I determine your teamwork grade for the semester. Here is the rubric for the teamwork grade: “A” Teamwork (18-20 points): Students in this category miss class rarely and only for the best reasons. They attend with the reading done every time and have something reflective to say about the reading. Their discussion posts push the class conversation forward. In the classroom, these students do not necessarily contribute the most or have the cleverest comments, but are dependable contributors, engage their classmates, and show enthusiasm for discussion. “B” Teamwork (16-18 points): Students in this category are similar to the ones above, but are not as regular in their contributions. They might complete the readings, but have little to offer about them. They might submit discussion posts, but not be interested in moving the conversation forward. In the classroom, they might contribute, engage their classmates, and show enthusiasm, but do so unevenly across class meetings. “C” Teamwork (14-16 points): Students in this category might have some highlights over the semester and even some consistency in some aspects of teamwork, but fall short of consistent contributions in every category throughout the semester. “D” Teamwork (12-14 points): Students in this category contribute little to the class discussion. Course Policies: During the class, cell phones and other electronic devices are prohibited. If you are a parent or are otherwise obligated to be available to your family via cell phone, then please discuss that situation with me, so I know that you have a good reason for keeping your phone turned on. The prohibition of electronics also extends to laptop computers (unless approved by the Disability Services Office). While laptops are great aides in studying, the focus in class is on class, not the computer screen. Further, the ability to take notes longhand is actually an important skill to develop, one that will be useful in any career you choose. If you do prefer to have your notes in a computer file, you will find that typing them from your handwritten notes will aid you greatly in digesting the material. For information on plagiarism, consult http://www.uwsp.edu/centers/rights. See Chapter 14, Student Academic Standards and Disciplinary Procedures, pages 5 -10, for the disciplinary possibilities if you are caught cheating. As an instructor deeply concerned with fairness in the classroom, I pursue each and every case of plagiarism and cheating. Please note that turnitin.com is used for the essay assignments. Life Happens: I understand you have a life outside this class. I understand that life might make it difficult to complete some assignments, attend class, or simply to do well. I do my best to be flexible because I know those circumstances are out of your control and my control. I’m on your team. I also know that some real learning has to take place in this class. You will have more opportunity in life if you understand history, read critically, and write well. This class has to be one of your priorities. I do my best to be flexible, but I have to adhere to some standards. If something comes up, let’s talk. Equity of Educational Access: If you have a learning or physical challenge which requires classroom accommodation, please contact the UWSP Disability Services office with your documentation as early as possible in the semester. They will then notify me, in a confidential memo, of the accommodations that will facilitate your success in the course. Disability Services Office, 103 Student Services Center, Voice: (715) 346-3365, TTY: (715) 346-3362, http://www.uwsp.edu/special/disability/studentinfo.htm. Note: The syllabus is a general plan for the course. Deviations announced in class may be necessary. Course Contacts: Name Email Why the History of Environmentalism Matters…Even If You Are Not an Environmentalist Week 1 Tuesday Introduction Wednesday Thursday Discussion Friday Lecture 9/4-9/7 Discussion Reading: Readings on Conflict Reading: Discover the Earth Day Post 9pm Reading: Discussion Posts Story www.nelsonearthday.net Reading: Beyond Earth Day Conservation’s Beginnings Week 2 Tuesday Lecture Wednesday Thursday Small Groups Friday Small Groups 9/11-9/14 Reading: FAR, Chapter Five Discussion Reading: Sand County, Part II Reading: Perspectives on Wildlife Post 9pm Reading: Discussion Posts Conservation (D2L) Week 3 Tuesday Discussion Wednesday Thursday Paper Workshop Friday Discussion 9/18-9/21 Reading: Raiding Devils (D2L) Paper Due 9pm D2L Reading: Five Student Essays The Limits of Conservation and the Rise of Environmentalism Week 4 Tuesday Lecture Wednesday Thursday Small Groups 9/25-9/28 Reading: Introduction by Linda Discussion Reading: The Storm over Silent Lear and Chapters 3, 8, 12, 14, Post 9pm Spring (D2L) and 17 in Silent Spring. Reading: Discussion Posts Reading: FAR, Chapter 6 Discussion Post 9pm Week 5 Tuesday Discussion Wednesday Thursday Paper Workshop 10/2-10/5 Reading: Woman vs. Man vs. Paper Due 9pm D2L Bugs (D2L) Environmentalism Matures: Citizen Action and Regulation Week 6 Tuesday Lecture Wednesday Thursday Discussion 10/9-10/12 Reading: FAR, Chapter 7 Discussion Reading: Good Earth Post 9pm Reading: Discussion Posts Possible Evening Talk Week 7 Tuesday Lecture Wednesday Thursday Small Groups 10/16-10/19 Reading: NIMBY to Civil Discussion Reading: Love Canal (D2L) Rights (D2L) Post 9pm Reading: Discussion Posts Discussion Post 9pm Week 8 Tuesday Discussion Wednesday Thursday Paper Workshop 10/23-10/26 Reading:Earthly Vision (D2L) Paper Due 9pm D2L The Challenge to Environmentalism Week 9 Tuesday Lecture 10/30-11/2 Reading: FAR, Chapter 8 Week 10 11/6-11/9 Tuesday Small Groups Reading: Encounters, Ch. 3 Week 11 11/13-11/16 Tuesday Discussion Reading: Wilderness (D2L) Week 12 11/20 Tuesday TBA Wednesday Thursday Small Groups Reading: ANWR (D2L) Discussion Post 9pm Wednesday Thursday Small Groups Reading: Glen Canyon (D2L) Discussion Post 9pm Wednesday Thursday Paper Workshop Paper Due 6pm D2L Using History to Think About the Future: Evaluating Debates Week 13 Tuesday Lecture Wednesday Thursday Discussion 11/27-11/30 Reading: First Along, Ch.9-10 Reading: Living Through, Ch. Self-Assessment 10pm D2L 1,7,8 Discussion Post 9pm Week 14 Tuesday Discussion Wednesday Thursday Discussion 12/4-12/7 Reading: Sand Mining TBA Reading: Sand Mining TBA Week 15 Tuesday Paper Workshop Wednesday Thursday Discussion 12/11-12/14 Paper Due 6pm D2L Five Student Essays Enduring Understandings, Lasting Questions Final Exam Paper Due 9am D2L – Meet in 224 CCC Friday Discussion Reading: CNRA (D2L) Reading: Sandhill (D2L) Reading: Discussion Posts Possible Optional Field Trip Friday Discussion Reading: Five Student Essays Self-Assessment 10pm D2L Friday Small Groups Reading: Earth Year (D2L) Friday Small Groups Reading: Love Canal II (D2L) Reading: Discussion Posts Friday Discussion Reading: Five Student Essays Friday Discussion Reading: ANWR II (D2L) Reading: Discussion Posts Friday Discussion Reading: Glen Canyon II (D2L) Reading: Discussion Posts Friday Discussion Reading: Five Student Essays Friday Discussion Reading: Sand Mining TBA Reading: Environmental Dilemma (D2L) Friday Discussion Reading: Sand Mining TBA Friday Discuss Final Essay