Insert title here - Engage - Department of Social Services

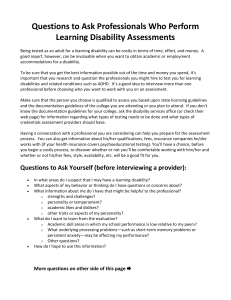

advertisement