DOCX 3379kB - Commonwealth Grants Commission

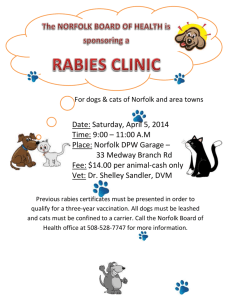

advertisement