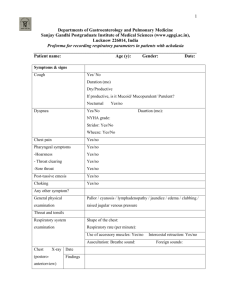

Problem 49- Cyanosis

advertisement

Cyanosis Index conditions Chronic pulmonary disease (COPD, fibrosis) Acute pulmonary disease (e.g. pneumonia, bronchiolitis) Pulmonary oedema Cyanotic congenital heart disease. Other causes of shunting. Clinical Skills Aware of use of home O2 therapy Provides advise on smoking Able to take focussed history to elicit underlying causes Able to perform cardiac and respiratory examination Able to recognise peripheral signs of chronic lung disease Able to differentiate central from peripheral cyanosis Able to distinguish main causes Able to select appropriate initial investigations (CXR, blood gases, ECG, pulmonary function tests, echocardiography lung scan) Able to eludidate clinical findings and investigations Can initiate treatment for acute ad acute cardiac failure Can monitor O2 therapy Professional behaviour Appropriate approach to Down’s syndrome baby with congenital heart disease Practical skills Can perform ECG, spirometry and PEFR Can take atrial blood gases Can explain invasive procedures (bronchoscopy, cardiac catheterisation, imaging) Can administer controlled oxygen therapy Can explain various forms of assisted ventilation Recognises and initiated acute management in severe cardiac and respiratory failure while calling for expert assistance Basic Medical Sciences Physiology of ventilation, perfusion and oxygenation (including function of haemoglobin and oxygen dissociation) Role of erthropoietinses. Abnormal Haemoglobins. Met and Sulf – Hb Development of the heart and circulation Clinical Sciences Pathophysiology of chronic lung disease and respiratory failure Pathophysiology of cyanotic congenital heart disease Differences between central and peripheral cyanosis. Causes of peripheral cyanosis. Causes of Reynauds. Population Health Sciences Epidemiology of COPD and occupational lung disease COPD Chronic bronchitis and emphysema Cough and sputum for more than 3 months in 2 consecutive years Pathology Epidemiology Persistent inflammation of the bronchi (bronchitis) and damage of the smaller airways and alveoli (emphysema). Narrowing of the airways resulting in obstructive airflow. 3 million people in the UK suffer COPD Affects mainly over 40s, more common with increasing age Men > women Risk factors Histology SMOKING Air pollution Poor working conditions Genetic risk (alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency 1/100 COPD sufferers) Airway hypersensitivity IV drug use (“% IVDUs) Immunodeficiency syndromes – HIV Vasculitis syndrome Connective tissue disorders Bronchitis – mucous gland hyperplasia, atrophy, squamouse metaplasia, ciliary abnormalities, variable amounts of smooth muscle hyperplasia, inflammation and bronchial wall thickening. Emphysema – focal destruction limited to the bronchioles and central portion of the acini. History: Examination: Cough – 3 months for 2 years, productive, ‘smokers cough’ Short of breath and wheeze – on exertion, worsening over time if smoking continues Sputum Recurrent chest infections Vague symptoms – weight loss, tiredness, ankle swelling Chest pain and coughing up blood are not common features SMOKER Normal respiratory examination in early or mild disease Clubbing Wheezing Hyperinflation Diffusely decreased breath sounds Hyperresonance on percussion Prolonged expiration Coarse crackles Obese Distant heart sounds Complications: Investigation: Cor pulmonale Respiratory failure Spirometry – reduced FEV1 (severity dependant) mild:>80%, moderate 50-79%, severe 30-49%, very severe <30% predicted Chest x-ray – hyper inflation, thickened inflamed scarred airways CT 2D echocardiogram 6-minute walking distance Electrocardiogram Right sided heart catheterization ABG Alpha1-antitrypsin measurement (normal 3- 7mmol/L) Management: Smoking cessation Bronchodilators Management of inflammation – systemic and inhaled corticosteroids Manage infection – common infections include S. Pneumonia H. Influenza and M. Catarrhalis Management of sputum – mucolytic agents eg N-acetylcysteine PPI for exacerbations and the common cold Oxygen therapy and hypoxaemia Flu vaccinations Long term monitoring and end-of-life care Prognosis 4th leading cause of death Cystic Fibrosis Most common lethal inherited disease in white people. Disease of the exocrine gland function that involves multiple organ systems, but chiefly respiratory infections, pancreatic enzyme insufficiency and associated complications in untreated patients. Pathology Epidemiology Defects in the CFTR gene. Results in decreased secretion of the chloride ion and increased reabsorption of sodium and water across epithelial cells. Results in reduced height of the epithelial lining fluid and decreased hydration of mucus, thicker mucus promoting infection and inflammation. Increase in viscosity of secretions in the respiratory tract, pancreas, GI tract, sweat glands and other exocrine tissues. Whites of northern European origin – 1/3,200 Hispanics – 1/9,200 African Americans – 1/15,000 Asian Americans – 1/31,000 Females show greater deterioration of pulmonary function than men causing younger age at death Risk factors Histology CFTR gene mutation (1604 mutations recognised) Thickened epithelial fluid lining. Classification: Aetiology: CFTR gene mutation History: Examination: Median age of diagnosis – 6-8months Neonates – meconium ileus and anasarca Infancts – wheezing, coughing, recurrent RTIs, pneumonia. Steatorrhoea, failure to thrive Children – pancreatic insufficiency, chronic cough, sputum production. Nose – rhinitis, nasal polyps Respiratory – tachypnoea, respiratory distress, wheezes, crackles, cough, increased anteroposterior diameter of chest, clubbing, cyanosis, hyperresonant chest upon percussion GI – abdo distension, hepatosplenomegaly, rectal prolapse, dry skin (vita deficiency), cheilosis (vitB complex deficiency) Other – scoliosis, kyphosis, submandibular and parotid gland swelling, aquagenic wrinkling of the palms. Complications: Investigation: Respiratory – pneumothorax, massive recurrent or persistent haemoptysis, nasal polyps, persistent and chronic sinusitis GI - meconium ileus, interssusception, gastrostomy tube placement for supplemental feeding, rectal prolapse Guthrie testing. Sweat test – high chlorise Imaging – pulmonary nodules resulting from abscess, infiltrated with or without lobar atelectasis, marked hyperinfiltration with flattened domes of the diaphragm, thoracic kyphosis, bowing of the sternum Pulmonary function testing Management: Diet and exercise – normal diet with additional energy and unrestricted fat intake. High energy, high fat diet, with additional supplemental vitamins (especially fat soluble) and minerals. Physiotherapy Involvement of – surgeons, otolaryngologist, endocrinologist, cardiologist, transplant team Assisted ventilation Pancreatic enzymes, vitamins, bronchodilators, mucolytic agents, antibiotics May need lung transplantation Prognosis Median survival is 36.9 years 80% should reachg adulthood with treatment Pneumonia Inflammation of the lung tissue, usually more serious than bronchitis. Sometimes bronchitis and pneumonia occur together – bronchopneumonia Pathology Epidemiology Viral or bacterial infection of the lungs. Inflammatory condition of the lungs, particularly the alveoli. Spread through droplets. Most common in children less than 5 and over 75. Risk factors Histology Age – young or elderly Low immunity Comorbidities Pathogen invasion leased to cell death or apoptosis, causing an inflammatory immune response. Classification: Aspiration – inhalation of oropharyngeal or gastric contents Bacterial - Strep pneumonia, pseudomonas aeruginosa. Viral – largest proportion of aediatric pneumonias (influenza, RSV, adenovirus, parainfluenza)) Community acquired – usually mycoplasmal. Also strep pneumonia (penicillin sensitive and resistant), H influenza, M catarrhalis (these 3 accound for 85%) Congenital – true congenital (established at birth, transmission through haematogenous, ascending or aspiration), intrapartum (during passage in the birth canal), postnatal (in first 24hrs after birth) Fungal – usually endemic (eg H capsulatum, C immitis) or opportunistic (eg Candida and Aspergillus) Chlamydial – pneuminiae (adolescents or young adults), psittaci(following bird exposure) or trachomatis ~(cause of STDs, pneumonia in infants and young children). History: Examination: Cough, fever, sweats, rigor, poor appetite, generally unwell. Headaches, aches and pains. Yellow/green sputum, may be bloodstained. May be breathless, tachypnoeaic and tight chest pain if plauritic infection Temperature, tachycardia, respiratory distress, rales, signs of consolidation, pleural rub. Extrapulminary findings may include: meningitis, skin lesions, rheumatologic and allergic reactions. Complications: Investigation: Sepsis and shock Bloods Imaging – Cultures – blood and sputum Thoracentesis Management: Thoracentesis Oxygen and ventilation Antibiotics Corticosteroid therapy CURB-65 – useful for determining need for hospital administration: C – confusion U – ureal > 7mmol/l R – Respiratory rate > 30 B – Bp SBP <90mmHg, DBP <60mmHg 65 – aged >65 Prognosis Dependant on the underlying cause, comorbidities and complications. 25% usually require hospitalisation. Bronchiolitis Acute inflammatory response injury of the bronchioles usually caused by a viral infection Pathology Epidemiology Very contagious. Virus spread by airborne droplets. Increased nasal secretions, bronchial obstruction and constriction, alveolar death, mucus debris, viral invasion, air trapping, atelectasis, reduced ventilation leading to ventilation/perfusion mismatch, labored breathing 1/9 infants contracts bronchioloitis in the first year of life during fall and winter, 10% require hospital admission. Low socioeconomic status can adversely affect outcome. Higher incidence in boys. Risk factors Aetiology Close contact with infection 90% caused by RSV Others – parainfluenze virus types 1, 2 and 3, influenza B, echovirus, rhinovirus, adenovirus (1, 2 and 5 in particular), mycoplasma (mainly in school aged children) History: Examination: Cough, dyspnoea, wheezing, poor feeding, hypothermia or hyperthermia. Hypo/hyperthermia, otitis media, tachpnoea, nasal flaring, intercostal retraction, subcostal retraction, irritability, fine rales, wheezing, hypoxia Complications: Investigation: Usually none In severe disease – respiratory failure Diagnosis mainly on clinical findings Septic screen Viral testing Pulso oximetry Nasopharyngeal aspirate Imaging Chest X-ray Management: May require oxygen Bronchodilators - Salbutamol (nebs, inhaler or IV) Maintain adequate hydration Prognosis Infectious self limiting disease Pulmonary oedema Pathology Cardiogenic – increased pulmonary capillary pressure, decreased plasma oncotic pressure, increated negative intersitinal pressure, damage to the alveolar-capillary barrier, lymphatic obstruction or idiopathic mechanism. Neurogenic – relatively rare, increased pulmonary interstitial and alveolar fluid, develops within a few hours of neurologic insult. Classification: Aetiology: Cardiogenic – extravasation of fluid from the pulmonary vasculature into the interstitium and alveoli of the lung. Neurogenic – follows neurological insult Cardiogenic – mitral stenosis, atrial myxoma, thrombosis of a prosthetic valve, cor tritriatum, acute MI or ischemia, salty diet, non compliance with diuretics, severe anaemia, sepsis, thyrotoxicosis, myocarditis, chronic valve disease Neurogenic – SAH, cerebral haemorrhage, epileptic seizure, head injury, MS, nonhaemorrhagic stroke, bulbar poliomyelitis, air embolism, brain tumour, ECT, bacterial meningitis, cervical spinal cord injury. History: Examination: Cardiogenic – symptoms of left heart failure, sudden onset breathlessness, anxiety, feeling of drowning, profuse diaphoresis, 24hr onset dyspnea Neurogenic – follows CNS insult, dyspnoea, mild haemoptysis Cardiogenic - hypoxia, increased sympathetic tone, tachypnoea, tachycardia, agitated, confused, hypertension, fine creps or wheezes, jugular venous distension, aortic stenosis, aortic regurge, mutral regurge, Neurological – tachypnoea, tachycardia, bibasilar crackles, respiratory distress, normal jugular venous pressue, fever. Complications: Investigation: Cardiogenic – respiratory fatigue and failure, sudden cardiac death Neurogenic – prolonger hypoxic respiratory failure, haemodynamic instability, nosocomial infections, death. Cardiogenic – bloods (anaemia, sepsis,U+E), imaging (enlarged heart, inverted blood flow), ABG, SpO2, ECG (LV hypertrophy) Neurogenic – no specific lab study, CXR shows bilateral alveolar filling with normal heart size, Management: Cardiogenic – Oxygen, ventilator support, preload reduction (NTG, loop diuretics), afterload reduction (ACE-i, angiotensin II receptor blockers), surgery (intra-aortic balloon pumping, ultrafiltration), diet (low salt) Neurogenic – focus on the underlying cause.may need O2 therapy. Prognosis Cardiogenic – hospital mortality rates can be as high as 20%, associated with MI with a mortality rate of 40%. Mortality rate approaches 80% if hypotensive Neurogenic – pulmonary oedema usually resolved within 48-72 hrs in the majority of patients... early stage cardiogenic – interstitial pulmonary oedema, cardiomegaly, left pleural effusion. Neurogenic mechanism Neurogenic - bilateral alveolar filling process and a normal-sized heart. This may mimic congestive heart failure with cephalization of blood flow, although other features of heart failure, such as septal Kerley B lines, are usually not evident Cyanotic congenital heart disease Heart defect present at birth resulting in low blood oxygen levels. There may be more than one defect. Pathology Coarctation of the aorta Critical pulmonary valvular stenosis Ebstein’s anomaly Hypoplastic left heart syndrome Interrupted aortic arch Pulmonary valve atresia Pulmonic stenosis with an atrial or ventricular septal defect Some forms of total anomalous pulmonary return Tetraolgy of Fallot Total anomalous pulmonary venous return Transposition of the great vessles Tricuspid atresia Truncus arteriosus Risk factors Chemical exposure Genetic and chromosomal syndromes (eg Downs, trisomy 13, Turners, Marfans, Noonan syndrome, Ellis-van Creveld) Infections (eg rubella) during pregnancy Poorly controlled blood sugar during pregnancy Medications taken during pregnancy Aetiology: The normal blood flow through the heart and lungs in altered (right to left shunt). History: Examination: Cyanosis Dyspnoea Anxiety, hyperventilation, sudden increase in cyanosis, fatigue, sweating, syncope, feeding problems / reduced appetite, puffy eyes or face Cyanosis Clubbing Abnormal heary sounds Heart murmur Lung crackles Complications: Investigation: Arrhythmias Brain abscess Heart failure Haemoptysis Impaired growth Infectious endocarditis Polycythemia Pulmonary hypertension stroke CXR FBC Pulse ox ABG ECG Echo-Doppler Transoesophageal echocardiogram MRI heart Management: Get rid of excess fluid Help the heart pump harder Maintain blood vessel patency Treat abnormal heartbeats or rhythms Prognosis Dependant on defect Some cause sudden death Congenital heart defects Presentation – dependant on the size of the defect. Ease to fatigue, recurrent respiratory chest infections, exertional dyspnoea Signs of pulmonary arterial hypertension, atrial arrhythmias, mitral valve disease. Palpable pulsation of the pulmonary artery, ejection click, S1 may be split, S2 often widely split, may have rumbling middiastolic murmur Risks in alcohol use and illicit drug use, some have genetic predispositions Left to right shunt with developed pulmonary hypertension and cyanosis: Eisenmenger’s syndrome Atrial septal defect: Ostium secundum Atrial septal defect – ostium primum 75% of ASDs female 2:1 male Incomplete adhgesion between the flap valve associated with the foramen ovale and the septum secundum after birth 15-20% of ASDa female 2:1 male Incomplete fusion of the septum primum with the endocardial cushion Atrial septal defect – sinus venosus Coronary sinus ASD 5-10% ASDa female 2:1 male Abnormal fusion between the embryologic sinus venosus and the atrium May occur on a familial basis Unroofed coronary sinus and persistent left superior vena cava which drains into the left atrium Aortopulmonary septal defect Ventricular septal defect: Uncommon Deficiency in the septim between the aorta and pulmonary artery Deficiency of growth or a failure of alignment or fusion of component parts of the ventricular septum. Patent ductus arteriosus Transposition of the great vessels Persistent communication between the descending thoracic aorta and the pulmonary artery. Fairly common and usually spontaneously close The aorta and the pulmonary vein are switched Ebstein’s anomaly Hypoplastic left heart syndrome Rare defect involving the tricuspid valve. Deep lying valves leaflets which are larger than normal Parts of the left side of the heart (mitral valve, left ventricle, aortic valve and aorta) do not develop completely Truncus arteriosus Total anomalous pulmonary venous return A single blood vessel comes out of the left and right vntricle instead of the normal two (pulmonary artery and the aorta) None of the four pulmonary veins is attached to the left artrium (usually returned to the right atrium), a septal defect must exist for the infant to survive Tricuspid atresia Coarctation of the aorta The tricuspid valve is missing or abnormally developed., blocking blood flow from the right strium to the right ventricle. Fallot’s tetralogy One of the most common congenital heart disorders Often associated with trisomy 21 (Down’s syndrome) Pathology Epidemiology 1. Right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (infundibular stenosis) 2. Ventricular septal defect 3. Aorta dextroposition 4. Right ventricular hypertrophy A few children also have atrial septal defect 10% of congenital heart defects 3-6 / 10,000 births Risk factors Maternal rubella and other infections, poor prenatal nutrition, maternal alcohol, older maternal age, maternal phenylketonuria, maternal diabetes. Aetiology: Unknown Genetic studies suggest multifactorial aetiology History: Examination: Cyanosis (during feeding, crying, etc), exertional dyspnoea worsening with age, haemoptysis due to rupture of the bronchial collaterals in older children Smaller than expected for age. Finger and toe clubbing from 3-6 months. Systolic thrill usually present anteriorly along the left sterna border. Harsh systolic ejection murmur over pulmonic area and left sterna border. S2 is usually single. Murmurs disappear during cyanotic episodes. RV predominance on palpation May have a bulging left hemithorax Aortic ejection click Squatting position (compensatory mechanism) Scoliosis (common) Retinal engorgement Haemoptysis Complications: Investigation: Worsened by acidosis, stress, infection, posture, exercise, beta-adrenergic agonists, dehydration, closure of the ductus arteriosus. Haematological studies – raised haemoglobin and haematocrit. SpO2 65-70%, hyperviscosity and coagulopathy ABG and pulse ox – vary O2 sats, pH and pCO2 are normal. Radiological studies – CXR: classic boot-shaped appearance ECG – right axis deviation, RV enlargement, partial or complete RBB block. Cardiac catheterization and angiography Complications from surgery – heart block, residual entricular septal defects, ventricular arrhythmias, late postoperative death. Management: Oxygen – don’t provoke during cyanotic episode IV propanolol in severe episode to relax muscle spasm. Surgery Prognosis Without surgery – mortality rates 30% age 2, 50% age 6 Sudden death in 1-5% Most who survive develop congestive heart failure by age 30 With surgery – 40% reduction in death. Tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia – 50% survive to age 1, 8% survive to 10 years. Pneumothorax Presence of air or gas in the pleural cavity. Pathology Epidemiology Spontaneous – rupture of the blebs and bullae. Primary spontaneous has no underlying disease usually related to increased shear forces in the apex Tension – disruption of the visceral plaura, parietal pleura or the tracheobronchial tree. Rupture forms a one way valve. Pneumomediastinum – excessive intra-alveolar pressure leading to rupture of the perivascular alveoli. Air escapes into the surrounding connective tissue and dissects into the mediastinum. Primary, secondary and recurring spontaneous pneumothorax – incidence underestimated, 10% are asymptomatic. 20-30. 7.4-18 / 100,000 (age dependant) COPD 26/100,000 persons Iatroenic and traumatic – 5-7/10,000 ospital admissions. 1-2% all neonates. Tension – complication in 1-2% idiopathic spontaneous pneumothorax. 1.4% all patients with TB. Pneumomediastinum – young healthy patients without serious underlying pulmonary disease. 4th decade of life. 1/100,000 hospital admissions. Risk factors Primary spontaneous – tall young people without lung disease, smoking, Marfan syndrome, pregnancy, familial Secondary spontaneous – COPD, asthma, immunodeficiency, necrotizing pneumonia, TB, sarcoidosis, CF, bronchogenic carcinoma, metastatic malignancy, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, inhalation and IVDU, interstitial lung diseases. Iatrogenic and traumatic – needle aspiration biopsy, transbronchial or pleural biopsy, throacentesis, thacheostomy etc. Tension – blunt or penetrating trauma, barotraumas, pneumoperitoneum, acupuncture, etc. Pneumomediastinum – asthma, RTI, parturition, emesis, severe cough, mechanical ventilation, trauma, athletic competition. Classification: Spontaneous / primary spontaneous Tension Pneumomediastinum History: Examination: Spontenous and iatrogenic – usually develops at rest. Not associated with trauma. No clinical signs before pneumothorax. Acute onset chest pain and SOB. Chest pain severe and stabbing, radiated to the ipsilateral shoulder, worsens on inspiration Tension – chest pain, dyspnoea, anxiety, fatigue, acute epigastric pain. Pneumomediastinum – 67% chest pain, 42% persistent cough, 25% sore throat, 8% dysphagia, SOB, vomiting and nausea. Respiratory – respiratory distress, tacypnoea, asymmetrical lung expansion, distant or absent breath sounds, transmitted lung sounds, hyperressonant percussion, decreased tactile fremitus, adventitious lung sounds (crackles, wheezes, ipsilateral finding) Cardiovascular – tachycardia, pulsus paradoxus, hypotension, jugular venous distension, cardiac apical displacement. Spontaneous / iatrogenic – tachycardia, tachypnoea and hypoxia Complications: Investigation: Misdiagnosis Hypoxic respiratoy failure, respiratory or cardiac arrest, haemopneumothorax, bronchpulmonary fistula, pulmonary oedema, empyema, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium pneumoperitoneum, pyopneumothorax. Complications of surgical procedures – failure to cure the problem, acute respiratory distress or failure, infection of the pleural space, cutaneous or systemic infection, persistent air leak, reexpansion pulmonary oedema, pair at the site of the chest tube insertion, prolonged tube drainage and hospital stay. ABG - acidaemia, hypercarbia, hypoxaemia CXR – linear shadow of visceral pleura, ipsilateral lung edge parallel to chest wall, deep sulcus sign, small pleural effusion, mediastinal shift, airway or parechymal abnormalities Transillumination – in neonates Chest CT – distinguish between bullae and pneumothorax, underlying emphysema, determine exact size Ultrasonography - Management: Prehospital – ABC, give O2. Needle decompression in tension pneumothorax. Hospital – ABCs, primary and secondary spontaneous; needle aspiration if small, pigtail catheter if larger. Pleurodesis decreases risk of recurrence. Iatrogenic and traumatic; aspiration, recurrence not usually a factor. In small pneumothorax no intervention may be needed – give oxygen. Tension; life-threatening – needle decompression Thoracotomy - Prognosis Primary, secondary and recurring spontaneous pneumothorax – complete resolution takes approximated 10 days. Typically benign and often resolves without medical attention. Recurrences usually strike within 6 months to 3 years. 5 year recurrence rate is 28-32% for primary, 43% for secondary. Recurrences more common in those who smoke. Tension – rapidly progresses to respiratory insufficiency, cardiovascular collapse and death is unrecognised and untreated. Prognosis depends of associated injuries and morbidities. Pneumomediastinum – generally benign self-limiting condition. Malignant or tension pneumomediastinum have comorbid conditions often related to trauma. No reports of fatal outcome with spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Mortality rate 70% in patients with pneumomediastinum secondary to Boerhaave syndrome even with surgical intervention. Spontaneous pneumothorax Tension Oneumomediastinum Pleural effusion Clinical importance ranges from incidental manifestations of cardiopulmonary diseases to symptomatic inflammatory or malignant disease. Pathology Epidemiology Normal pleural space contains approximately 1ml fluid representing the balance between hydrostatic and oncotic forces in the visceral and parietal pleural vessels and extensive lymphatic drainage. Pleural effusion result from disruption of this balance. 1 million cases per year in the US. 324/100,000 in industrialised countries. Aetiology: Transudates: congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, atelectasis, hypoalbuminaemia, nephritic syndrome, peritoneal dialysis, myxoedema, constrictive pericarditis. Exudates: parapneumonic causes, malignancy (carcinoma, lymphoma, mesothelioma), pulmonary embolism, collagen vascular conditions (RA, SLE), TB, asbestos exposure, pancreatitis, trauma, drug use, sarcoidosis. History: Examination: Dyspnoea related to distortion of the diaphragm and chest wall more than hypoxaemia. Signs of underlying lung or heart disease. Less commonly – mild non-productive cough or chest pain. Constant chest pain suggests invasive cancers. Productive cough suggests pneumonia. Pleuritic chest pain suggests embolism or inflammatory pleural process. Persistent systemic toxicity evidenced by fever, weight loss and inanition suggests empyema. Normal examination til 300 ml effusion. Decreased breath sounds Dullness to percussion Decreased tactile fremitus Egophony (E-to-A change) Pleural friction rub Mediastinal shift away from the effusion. Complications: Investigation: Permanent lung damage Infection causing abscess or empyema Frankly purulent fluid indicates empyema, putrid odour suggests anaerobic empyema, milky Pneumothorax opalescent fluid suggests chylothorax, bloody fluid suggests trauma, malignancy or asbestos related syndromes. Exudate if: pleural fluid to serum protein ratio >0.5, fluid to serum LDH >0.6, pleural fluid LDH > 2/3 the upper limit of normal serum value. Transudate: pleural fluid LDH >0.45 upper limit normal serum level, pleural fluid cholesterol > 45 mg/dl, pleural fluid protein >2.9 g/dl. Imaging: CXR, USS, CT Diagnostic thoracentesis, therapeutic thoractentesis. Tube thoracostomy, pleurodesis or pleural sclerosis Management: Treat the underlying cause. Drainage Surgical intervention: video assisten thoracoscopy, pleural sclerosis, implanted shunts, surgery to close defects Diet – restrict fat Monitoring Prognosis Varies depending of underlying cause Malignant disease have a poor prognosis – median survival 4 months, mean survival less than 1 year. Peripheral vascular disease (atherosclerotic disease) Disease affecting the large and medium sized arteries. Pathology Epidemiology Endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, uild up of lipids, cholesterol, calcium and cellular debris within the intima of the vessel wall. Build up results in plaque formation, vascular remodelling, acute and chronic luminal obstruction, abnormalieies of blood flow and diminished blood supply to target organs. Men > women >40 years Risk factors Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, CRP, elevated fibrinogen, familial hypercholesterolaemia, History: Examination: Dependant on vascularture affected CNS – stroke, reversible ischarmic neurologic deficit, transient ischaemic attack. Peripheral – intermittent claudication, impotence, nonhealing ulceration and infection of extremities. Visceral ischarmia – signs and symptoms of target organ failure. Mesenteric angina – epigastric or periumbilical postprandial pain, haematemesis, haematochezia, melena, diarrhoea, nutritional deficiencies, weight loss. AAA Mild disease appears clinically normal. Hyperlipidaemia CVD – diminished carotid pulses, carotid artery bruits, focal neurological defecits. PVD – decreased peripheral pulses, peripheral arterial bruits, pallor, peripheral cyanosis, gangrene and ulceration. AAA – pulsatile abdominal mass, peripheral embolism, circulatory collapse Atheroembolism - livedo reticularis, gangrene, cyanosis, ulceration, digital necrosis, GI bleed, rectal ischaemia, cerebral infarction, renal failure. Investigation: Lipid profile – elevated LDL, high triglycerides, low HDL Blood glucose and HbA1C – raised USS – evaluation of arteries showing intima-media thickening MRI – thickening of blood vessel wall and characterise plaque composition. Management: Control risk factors. Dietary and pharmacologic treatment of hypertension Control DM Treatment of familial hypercholesterolaemia Prognosis Dependant on systemic durden of disease, vascular bed(s) involved, degree of flow limitation. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis Specific form of chronic, progressive fibrosing interstitial pneumonia of known cause. Pathology Epidemiology Current hypothesis: exposure to inciting agent (eg smoke, environmental pollutants, environmental dust, viral infections, GORD, chronic aspiration) causing aberrant activation of alveolar epithelial cells provokes migration, proliferation and activation of mesenchymal cells with the formation of fibroblastic/ myofibroblastic foci, leading to the exaggerated accumulation of extracellular matrix with the irreversible destruction of the lung paraenchyma. Activated alveolar epithelial cells release potent fibrogenic cytokines and growth factors. Normal wound healing doesn’t occur. Excess apoptosis and fibroblast resistence to apoptosis contributes to fibroproliferation and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. No large scale studies are available. Incidence: Males – 10.7/100,000 persons per year Females – 7.4/100,000 persons per year Prevalence: Males – 20/100,000 Females – 13/100,000 Aetiology: Histology Undefined Possibly exposue to inciting agents Heterogenous, variegates appearance with alternating areas of healthy lung, interstitial inflammation, fibrosis and honeycomb change resulting in a patchwork appearance. History: Examination: Non-specific history Exertional dysponoea, non productive cough Systemic symptoms include weight loss, lowgrade fever, fatigue, arthralgia or myalgias Symptoms for 1-2 years before diagnosis is made 5% have no presenting symptomes Fine bibasilar inspiratory (Velcro) crackles. Digital clubbing (25-50%) Pulmonary hypertension Complications: Investigation: Pulmonary hypertension Acute exacerbation of pulmonary fibrosis Respiratory infection Acute coronary syndrome Thromboembolic disease Routine labs are non-specific, can be used to rule out other causes of interstitial lung disease CRP and ESR may be elevated Chronic hypoxaemia Imaging – CXR (peripheral reticular opacities at Adverse medication effects Lung cancer lung bases, honeycombing, lower lobe volume loss). CT (subpleural honeycombing) 4 criteria: subpleural basal predominance, reticular abnormality, honeycombing with or without traction bronchiectasis, absence of inconsistent features. Lung function tests Management: Stop smoking Oxygen therapy Vaccination against influenza and pneumococcal Lung transplantation Diet – maintain ideal bodyweight Remain active Prognosis Poor prognosis – 2-5 year from time of diagnosis Death rates increase with age, higher in men than women, worse during winter 60% dies from their idiopathic fibrosis as opposed to dying with it. Asthma Pathology Epidemiology Compolex pathophysiology involving airways inflammation, intermittent flow obstruction and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. The mechanism of inflammation may be acute, subacute or chronic with the presence of airway oedema and musuc secretion contributing to airway obstruction and brochial reactivity. 5-10% of the population. Overall prevalence rate of exercise induced bronchospasm is 3-10% in people without asthma or allergies, 12-15% in the whole population. In the UK 1,200 deaths from asthma in the UK, 40 were under 40 (average of 3 deaths a day) Risk factors Histology FH asthma, allergy, sinusitis, rhinitis, eczema, nasal polyps. Social factors – smoking, workplace, education level. Mononuclear cell and eosinophil infiltration, mucus hypersecretion, desquamation of the epithelium, smooth muscle hyperplasia and airway remodelling. Aetiology: Environmental allergens (dustmites, animal allergens. Cockroach allergens, fungi), Viral RTIs, GORD, chronic sinusitis or rhinitis, aspirin or NSAID hypersensitivity, use of beta-adrenergic receptor blockers, obesity, environmental pollutants, tobacco smoke, occupational exposure, irritants (sprays, paint fumes), emotional factors, stress, perinatal factors. History: Examination: Wheezing, cough, recurrent bronchitis, bronchiolitis, pneumonia, persistent cough and coryza, croup, chest rattling, chest tightness, recurrent chest congestion. May be exercise induced. Mild: breathless, talk in sentences, can lie down, increased resp rate, accessory muscles not really used, HR <100, SpO2 >95% in air. Moderate: RR increased, accessory muscle used, supraclavicular and intercostals muscle recession, nasal flaring, HR 100-120bpm, loud expiratory wheeze, SpO2 91-95% in air, difficulty talking or feeding, may sit straight. Severe: breathless at rest, not eating, sit upright, broken sentences, agitated, RR>30, accessory muscles used, suprasternal retraction, HR>120, loud biphasic wheeze, SpO2<91 in air, hunched position (tripod) Imminent respiratory arrest: severe episode + drowsy and confused, severe hypoxaemia, may have a bradycardia. Complications: Investigation: COPD in severe asthma Serious respiratory infections eg pneumonia Pneumothorax Respiratory failure Status asthmaticus (severe asthma attacks that do not respond to treatments) Death Labs: blood and sputum eosinophils, elevated IgE CXR : may be normal, hyperinflation CT: bronchial wall thickening, bronchial dilatation, cylindrical and varicose bronchiectasis, reduced luminal area, mucoid impaction of the bronchi, centrilobar opacities, linear opacities, airtrapping, mosaic lung attenuation. ECG: sinus tachycardia Allergen skin test Spirometry – reduced peak flow and FEV1. Management: (see below) 1. Occasional used of relief bronchodilators 2. Regular inhaled anti-inflammatory agents 3. High dose inhaled steroids or low dose inhaled steroids plus long acting beta-agonist bronchodilator 4. High does inhaled steroids and regular bronchodilators 5. Addition of regular steroid tablets Prognosis Mortality as high as 0.86 / 100,000 interntationally. Mortality related to lung function with an 8-fold increase in the lowest quartile. Mortality also linked to management failure, smoking and comorbidities. High-resolution CT scan of the thorax obtained during inspiration demonstrates airtrapping in a patient with asthma. Inspiratory findings are normal. High-resolution CT scan of the thorax obtained during expiration demonstrates a mosaic pattern of lung attenuation in a patient with asthma. Lucent areas (arrows) represent areas of airtrapping. Clinical Skills notes Aware of use of home O2 therapy Useful website: http://www.homeoxygen.nhs.uk/2.php Provides advise on smoking Useful website: http://smokefree.nhs.uk/ They can provide a QuitKit with practical tools and advice Respiratory history and exam: Respiratory System Examples of presenting complaints Breathlessness • How is the patient normally? (Is this acute / chronic / acute or chronic?) • Onset, timing, duration, variability • Exacerbating factors e.g. allergic triggers, exertion, cold air • Relieving factors e.g. rest, medication • Associated symptoms e.g. cough, sputum, haemoptysis, pain, wheeze, night sweats, weight loss, oedema • Severity e.g. at rest? Only on exertion? Limiting ADLs? Cough • Onset, timing, duration, variation (e.g. changed chronic cough), diurnal variation • Productive / unproductive? Sputum • Onset, timing, duration, variation, diurnal variation • Colour • Consistency (viscous (fluid), mucous, purulent, frothy) • Quantity (teaspoon, cupful etc.) • Odour (fetid suggests bronchiectasis or a lung abscess) Haemoptysis • Origin (differentiate haemoptysis from haematemesis, sure it was coughed up?) • Onset, timing, duration, variation • Quantity • Colour (fresh blood or dark altered blood) • Consistency (liquid, clots, mixed with sputum) • Chest pain • Recent trauma to chest or elsewhere? • Recent / current DVT? • Weight loss, fever, night sweats? • Breathlessness? • Bleeding or bruising elsewhere? Respiratory System Examination Wash your hands Past Medical History Specific risk factors include: • Previous respiratory problems o Pneumonia can lead to bronchiectasis or pulmonary fibrosis o Tuberculosis can reactivate o Severe measles or whooping cough can lead to bronchiectasis o Asthma • Recent surgery o Dental surgery can lead to aspiration of purulent material or fragments of tooth o Abdominal, pelvic or orthopaedic surgery are risk factors for DVT and possible pulmonary embolus • Cardiac disease may lead to pulmonary oedema • Immunocompromise (e.g. HIV, immunosuppression post‐transplant surgery) may predispose to atypical infections Drug history and allergies • Inhalers, steroids, antibiotics, ACE inhibitors (may cause cough), oxygen therapy • Social history • Occupation (industrial hazards e.g. dusts, asbestos) • Smoking (pack years) • Pets • Overseas travel • Living conditions e.g. damp • Alcohol • Exercise, activities of daily living, independence Family history • Infections may be transmitted between family members • There is a genetic predisposition to allergic conditions e.g. asthma, emphysema Palpation Check trachea and apex beat for deviation Assess chest expansion anteriorly (normal >5cm, definitely abnormal <2cm) Assess tactile vocal fremitus Introduction, identification and consent General inspection of the bed area e.g. inhalers, nebuliser, oxygen mask, sputum pot General observation of the patient (colour, breathing, comfort, position, purse‐lipped breathing, nutritional state Percussion Starting at the apices, percuss from side to side anteriorly Auscultation Starting at the apices, auscultate from side to side anteriorly th and laterally with open mouthed breathing (clavicle to 6 rib, Inspection Inspect the hands for clubbing Look for tremor (flapping asterixis in respiratory failure, fine with beta‐agonists e.g. salbutamol) Assess pulse rate, rhythm and character (e.g. bounding in CO retention) whilst simultaneously assessing respiratory th 2 rate, rhythm, pattern and effort. Check for raised JVP (cor pulmonale) Look for respiratory disease in the eyes: o Horner’s syndrome o Chemosis (conjunctival oedema may be seen with hypercapnia 2° to COPD) Look for respiratory disease in the face and mouth: o Dental caries (may cause lung abscess by inhalation of debris) o Central cyanosis Expose the chest and inspect for: Shape o Barrel chest (hyperinflated in emphysema) o Severe kyphoscoliosis o Severe pectus excavatum (funnel chest) o Pectus carinatum (pigeon chest) +/‐ Harrison’s sulci Symmetry Scars Muscle wasting Chest versus abdominal (diaphragmatic) breathing Use of accessory muscles Recession (more common in children, but can be seen in adults with partial laryngeal/tracheal obstruction) midclavicular line; Axilla to 8 rib, mid axillary line). Note the presence of: o Vesicular (normal) breath sounds o Bronchial breathing o Rhonchi (wheezes) o Crepitations o Pleural rub o Assess for any change in these sounds after coughing (crepitations due to secretions will alter after coughing whereas those in fibrotic conditions won’t) Assess vocal resonance +/‐ whispering pectoriloquy (whisper 222) Repeat inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation (spine of scapula to 11th rib) on the back with the patient sitting forward This is a convenient time to palpate the cervical lymph nodes. Check sputum pot (volume, consistency, colour, odour, any haemoptysis) Assess peak flow Thank the patient Wash your hands Cardiac history and exam: Cardiac History Presenting complaints include: Chest pain Dyspnoea (SoB) Orthopnoea (SoB on lying flat that is relieved by sitting up) Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea (acute dyspnoea that wakes patient from sleep) Ankle oedema Cough, sputum, haemoptysis Dizziness Lightheadedness Presyncope and syncope Palpitations Nausea and sweating Claudication Systemic symptoms (eg fatigue, weightloss, anorexia, fever) Ischaemic heart disease risk factors: Age, smoking, hypertension, DM, FH, Hypercholesterolaemia, inactivity and obesity Chest pain Site – central substernal, across mid-thorax anteriorly, in both arms / shoulders, neck, cheeks, teeth, forarms, fingers, intrascapular region Onset – Acute Character – crushing, tight, constricting, squeezing, burning, ‘heaviness’ SoB Onset – acute, chronic, acute – on – chronic Associated symptoms 0 sweating, nausea, pain, cough, sputum, peripheral oedema, palps, nocturnal micturition, rapid weight gain Timing – on exercion? At rest? Constant? At night? Exacerbating factors – position (number of pillows – orthopnoea?) Alleviating factors – rest, medications, oxygen, sitting up straight Severity – how debilitating, effect of ADLs, excess tolerance Any respiratory diseases? Palpitations Ever had palpitations? Been aware the heart is racing? Anything provoke it? Sudden or gradual build up / stopping? How long does it last? Any other symptoms? Tap the rhythm – regular, irregular, irregularly irregular? Fast / slow? Syncope Sudden or brief loss of consciousness, with deficit of postural tone, spontaneous recovery Usually due to sudden transient hypotension, poor cerebral profusion Presyncope – feeling of imminent syncope eg faintness Radiation – neck, jaw, left arm Associations – sweating, nausea, SoB, palpitations Timing – on exertion? At reast? Exacerbations = exercise, excitement, stress, cold weather, after meals, smoking Alleviations – rest, medications, oxygen Severity – pain scale (1-10) Past Medical History Similar episodes, previous diagnoses, treatments and responses to them Previous cardiac surgery Hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, anaemia, DM, angina, MI, CVA, TIA, peripheral vascular disease, cardiac failure, rheumatic fever Factors against cardiac ischaemia as the cause of pain Character of pain: knife like, sharp, stabbing, aggravated by respiration Location of pain: left submammary area, left hemithorax Exacerbating factors: pain after exercise, specific body motion Drug history and allergies Antihypertensives, all cardiac drugs Drugs with cardia side effects, eg corticosteroids, salbutamol, theophylline, nifedipine, thyroxine Cardiac Examination Wash hands Introduction, identification and consent Inspect the bedspace for clues e.g. GTN spray Inspect the general appearance of the patient (colour, breathing, comfort, position, build) Inspect the patients hands for cardiac signs: o Nicotine staining o Vasodilatation/constriction, temperature o Sweating (suggests increased sympathetic drive) o Pallor of palmar creases o Peripheral cyanosis o Clubbing o Splinter haemorrhages o Osler’s nodes o Tendon xanthomas Check the presence of both radial pulses simultaneously. Assess rate and rhythm in one radial pulse (usually the right). Assess the character and volume of the brachial pulse (normal, slow rising, collapsing). Ask the patient if they have pain in their arm before checking for collapsing/waterhammer pulse (aortic regurgitation) Assess the character and volume of the carotid pulse (one side at a time) Look for cardiac signs in the eyes: o Subconjunctival pallor o Corneal arcus Look for cardiac signs in the face: o Malar flush (mitral stenosis) Look for cardiac signs in the mouth/lips: o Central cyanosis (under tongue or on mucous membranes inside lips) o High‐arched palate (Marfan’s) o Dental caries (may predispose to infective endocarditis) Position the patient at 45° and check for raised JVP (normal = 2 ‐ 4cm above sternal angle). Check for low JVP using hepatojugular reflux by compressing the liver and observing the JVP (will rise). Check for high JVP by sitting patient upright and looking near the ear lobes for venous pulsation. Identify the two main waves by palpating the carotid. Social History Occupation, smoking, alcohol cardiomyopathy), diet, stress (AF and Family History FH of IHD or CVA before the age of 65. Expose the patients chest and inspect the precordium o sternotomy scar o severe pectus excavatum o severe kyphoscoliosis o visible cardiac pulsation Palpate for the apex beat and parasternal heaves (outward displacement of the palpating hand by cardiac contraction e.g. in left ventricular hypertrophy) and thrills (palpable murmurs) Auscultate aortic, pulmonary, tricuspid and mitral valve areas Auscultate left axilla for mitral incompetence If extra sounds are heard, palpate the carotid pulse to time them with the first and second heart sounds Switch to the bell and auscultate the apex with the patient rolled 45° to the left (for mitral stenosis). Switch back to the diaphragm, sit the patient forward and auscultate at the 4th/5th intercostal space to the left of the sternum on held expiration (aortic regurgitation) Auscultate lung bases, assess for sacral oedema. If coarctation is suspected, auscultate to the left of the spine in rd th the 3 /4 intercostal space Sit the patient back and auscultate the carotids for bruits or a transmitted systolic murmur. Lay the patient flat, if they can tolerate it, and palpate for hepatomegaly. If the liver is enlarged, feel for pulsation (tricuspid regurgitation). Check the femoral pulses. Check synchrony with the radial pulse (radiofemoral delay in coarctation). Check for pitting oedema at the ankles. Check BP in both arms and lying and standing in one arm. Perform opthalmoscopy for hypertensive retinopathy Thank the patient and wash your hands. Basic Sciences Physiology of ventilation, perfusion and oxygenation (including function of haemoglobin and oxygen dissociation) Role of erthropoietinses. Abnormal Haemoglobins. Met and Sulf – Hb Met-haemoglobin: the iron heme group must initially be in the Fe2+ state to support oxygen and other gases binding and transport. It switches to the ferric (Fe3+) when bound to oxygen, forming methaemoglobin which can’t bind to more oxygen. Sulf-haemoglobin- haemoglobin bound to sulphun monoxide (SO) which bind iron in the heme without changing its oxidation state, they inhibit oxgen binding can cause toxicity (can also bind to cyanide (CN-), nitric oxice (NO) and sulphide (S2-). Haemoglobin: