OB: Dating in the Workplace

advertisement

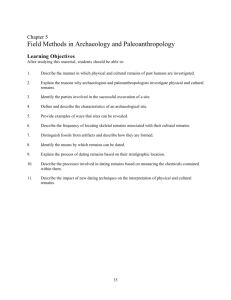

East Carolina University Dating in the Workplace An Organizational Behavior Approach John Murtha, Kylen Smith, Michael Blankenship 2012 In corporate America today we are seeing women fill positions they had never held before. This all started about 25 years ago when we began to see an influx from stay at home moms to college graduates. Gone are the days when women could only be housewives and secretaries; we live in a new era. Women are now holding positions that used to be dominated by men such as CEOs, Doctors, diplomats, sports-casters, firefighters, and even soldiers on the front lines. One such person is Indra K. Nooyi, CEO of Pepsi. Nooyi became President and CEO of PepsiCo on October 1, 2006 and is now in charge of their $66 billion in annual retail sales (Mergent, 2012). This is just one of many success stories, but with this success also came a new wave of issues in the modern workplace. Problems such as sexual harassment, sexual assault, and hiring biases are just a few. All of these issues stem from our lack of exposure to a gender balanced workforce. However, the biggest of all these issue is dating in the workplace. For years, this issue was the elephant in the room, in that it was not accepted, but it was an issue few corporations were ready to tackle at the time. A recent example of how corporations are taking a more firm stance against dating in the workplace is the firing of Boeing’s CEO. Harry Stonecipher was fired as Chief Executive Officer after just one year for having a consensual relationship with a female executive. Even though the employee did not directly report to Stonecipher, fraternization among co-workers is often prohibited in many companies regardless of organizational hierarchy. In the case of Boeing, workplace dating is not allowed as part of their code of conduct. Thus, the CEO and his mistress were blatantly violating a major company value. With that understanding the board of trustees was left with no choice but to terminate Stonecipher. This is an example of something that happens every day in the workplace, but due to the company’s high profile this instance was incredibly scrutinized by the public. This 1 directly affected the decision to let him go as it allowed Boeing to save face in the court of public opinion. (Isidore, 2005) To illustrate the prevalence of workplace dating one group member had a similar instance in their high school. Here, two of his teachers became romantically involved and decided to make their relationship public. Due to policies by the school board, the man was forced to cease his employment at that institution before he was able to propose to his future wife. These are two distinct examples of dating in the workplace: one giving someone the courage to make a decision to be with the person they love and the other forcing a company to terminate a high ranking executive. The examples given reinforce that there are many different ways to handle dating in the workplace. There are many schools of thought on dating in the workplace, but the one we will focus on is the theory of propinquity, or proximity. This theory has two different parts to it, functional and spatial propinquity. Functional refers to how easy it is for two people to interact and have a conversation, whereas physical refers to the actual spatial proximity between two people. (Pierce, 2006) To delve further into the two perspectives of this theory, two group members have personal examples of each: In many cases of functional propinquity the hierarchy of an organization provides a cultivating environment for a workplace relationship. In our group member’s personal experience they were on the executive board of a campus organization. The obligations of their position required them spending extensive amounts of time with board members on 2 a weekly basis. This created an ease for a familiarity between the two people who eventually engaged in a relationship. After spending several months interacting with the President of their organization the two eventually developed feelings towards one another. These feelings eventually manifested into a physical relationship that lasted several months. After that time the relationship ended abruptly and left the one of them emotionally distraught. These emotions immediately affected that person’s ability to handle the duties of their position and interact on a professional level as both parties had done before. It took some time to restore a level of professionalism, but the two are now able to carry on their duties with no tension. The alternate viewpoint of propinquity involves the physical distance of two coworkers influencing the ability to start a romantic relationship. Our second example involves a scenario where one of our group members became intimate with someone during a summer job. Here, he worked at a bar at a summer destination where the nightlife fostered a promiscuous ambiance. The two were in constant proximity of one another, as he was a bouncer assigned to protect her and other employees in a specific area of the establishment. One point worth noting, the female was a bartender and it is assumed, but not endorsed that many bartenders will have a few drinks during the course of a shift. Also, the two would share drinks and converse regularly after hours once the bar patrons had left. These contributing factors of proximity, alcohol, and a promiscuous setting had a direct correlation to the eventual relationship. This interaction between them was a brief summer fling, but both of them maintained a strong professional bond and are still friends today. 3 Organizational Behavior researchers care about work place dating because of the negative effects on the people in the relationship, their coworkers, and the company as a whole. Some examples of negative effects include higher employee turnover (as in Boeing example), decreased productivity (group member example one), and costly lawsuits. “For the employer, the benefits of banning romance appear to be primarily financial and administrative: there is a presumed (but contentious) net improvement in productivity plus a reduction in costs from sexual harassment suits arising from romances gone wrong, less the cost of replacing employees who may be fired for violations of a no-romance rule (Boyde, 2012).” Another important aspect OB researchers care about is the decline in employee motivation. Dating in the workplace has both positive and negative effects on those in the relationship. However, those in the relationship fail to realize their relationship’s effect on their co-workers through emotional contagion. For instance, if a couple expresses negative emotions in the workplace it is likely that their poor attitude will radiate to other employees, thus decreasing morale and motivation (Barsade, 2002). From management’s perspective, work place dating is an issue because they are responsible for the employees beneath them and their productivity. Anything affecting their employee’s ability to work more efficiently is counterproductive. Managers have a vested interest in their employee’s success because it reflects on their abilities to lead their team. As a manager, one has a duty to keep the company’s best interest in mind and in most instances dating in the workplace has proven to be an obstacle, not an asset. For example, “in The Society for Human Resource Management’s 2002 survey of workplace romance, 95% of HR professionals cited ‘‘potential for claims of sexual harassment’’ as a reason to ban or discourage workplace romance, whereas the second most cited reason, ‘‘concerns about lowered productivity by those involved in the romance,’’ was cited by just 46%” (SHRM, 2002). 4 The primary objectives of an organization are to maintain a sustainable competitive advantage and generate profits. Keeping that in mind, anything that takes away from those overall goals should be eliminated from their corporate culture. While some cases of dating in the workplace are acceptable, others do end negatively and in the past avoidance was the preferred strategy. However, recent studies estimate around 10 million new workplace romances each year compared to 14,200 sexual harassment suits. That equates to one instance of harassment in every 704 romances. It is also worth noting that only one in every 3-to-5000 harassment suits actually stems from a failed case of dating in the workplace. These new findings have forced companies to alter their way of handling this unique issue. “Cole suggests that companies need to have rules around office romance, but not outright bans. Policies should address what constitutes inappropriate behavior (for example, vindictive acts if the relationship ends) and any rules regarding managers dating subordinates. They should also indicate what action will be taken if a problem arises (Nelson, 2011).” (Pierce and Aguinis, 2009) In conclusion, there are always some types of problems with dating in the workplace from any stand point, whether it is with the organization or the direct manager. The times have changed to where people are forced to look at the issues at hand and address them before it does any harm to the company as a whole. Women and men will always interact with each other on the job where permitted but to what extreme does the company have a problem with them doing so. Dating in the workplace is not something unheard, it’s how the situation is handled within the different corporations that truly matters. 5 Bibliography Mergent, . (2012). PepsiCo Inc. In Mergent Online. Retrieved April 8, 2012, from http://www.mergentonline.com/companyfinancials.php?pagetype=analysis&compnumber=6581 SHRM (Society for Human Resource Management): 2002, Workplace Romance Survey (Item no. 62.17014) (SHRM Public Affairs Department, Alexandria, VA). Letterman case spotlights boss/employee relationships. (2009). HR Specialist: New York Employment Law, 4(12), 5. Boyde, C. (2010, December). The Debate over the Prohibition of Romance in the Workplace [Electronic version]. The Journal of Business Ethics, 97(2), 325-338. doi:10.1007/s10551-0100512-3 Barsade, S. G. (2002, December). The Ripple Effect: Emotional Contagion and Its Influence on Group Behavior [Electronic version]. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47(4), 644-675. Nelson, J. (2011, September 12). Is your policy on office dating updated for the twenty first century [Electronic version].Canadian Business, 84(14), 71. Pierce, C. A. and H. Aguinis: 1997, ‘Bridging the Gap Between Romantic Relationships and Sexual Harassment in Organizations’, Journal of Organizational Behavior 18(3), 197–215 Pierce, C. A., & Byrne, D. (1996). Attraction in organizations: a model of workplace romance [Electronic version]. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17, 5-32. Isidore, C. (2005, March 7). Boeing CEO out in sex scandal. In CNN Money. Retrieved April 12, 2012, from http://money.cnn.com/2005/03/07/news/fortune500/boeing_ceo/ 6