Ex-dividend - McGraw Hill Higher Education

advertisement

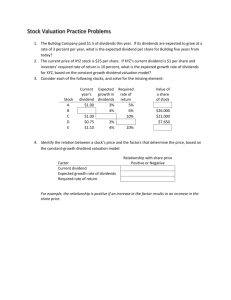

15-1 Fundamentals of Corporate Finance Second Canadian Edition prepared by: Carol Edwards BA, MBA, CFA Instructor, Finance British Columbia Institute of Technology copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-2 Chapter 16 Dividend Policy Chapter Outline How Dividends are Paid How Do Companies Decide on Dividend Payments? Why dividend Policy Should Not Matter Why Dividends May Increase Firm Value Why Pay Dividends? A Look at Tax Law Implications copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-3 Dividend Policy • Introduction Your objective as a financial manager is to undertake actions which will maximize the value of your firm. A cash dividend is a payment of cash by the firm to its shareholders. Some firms have a policy of low or no dividends, others have a policy of high dividends. The key question this chapter will pose is: Can you change the value of your firm by changing its dividend policy? copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-4 How Dividends Are Paid • Cash Dividends Regular cash dividends are generally paid quarterly. Under certain circumstances, the firm will pay an extra dividend. Such a dividend is a one-time event and is unlikely to be repeated. The word “extra” alerts shareholders to this fact. With all dividends, there is a payment date when the company mails cheques to shareholders. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-5 How Dividends Are Paid • Cash Dividends The key question is: Who receives the dividend cheque? Given that shares trade constantly, the company’s record of the names and addresses of its shareholders can never be up-to-date. As a consequence, the company arbitrarily sets a Date of Record. All shareholders recorded on the company’s books at this date receive the dividend, regardless of who actually owns the shares. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-6 How Dividends Are Paid • Cash Dividends Stock exchanges set a cut-off date, the ex-dividend date, two business days prior to the date of record. If you buy the shares on, or after, this date, you will not be on the company’s books on the date of record. As a consequence, you will not receive the dividend. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-7 How Dividends Are Paid • Cash Dividends Thus, stocks are said to trade: Cum dividend - with the dividend. If you buy a stock cum dividend, and you hold the shares until the ex-dividend date, then you would be on the company’s shareholder records and would receive the dividend. If you sell a stock cum dividend, you give-up the right to receive the dividend as well as giving-up the stock. Ex-dividend - without the dividend. Anyone buying a stock ex-dividend, is ineligible to receive the dividend. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-8 How Dividends Are Paid • Cash Dividends A company has declared a dividend with a payment date of June 30th. The date of record is Monday, June 6th. What Cum dividend Wed. 1 is the ex-dividend date? Ex-dividend – June 2nd Thur. Fri. Sun. x Sat. Mon. x 2 3 4 5 Count back 2 business days. 6 Date of Rec. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-9 How Dividends Are Paid • Cash Dividends The difference between buying a share cum and ex-dividend is you do not receive the dividend. Thus, you should expect that on the ex-dividend date, the price of the stock should drop by the value of the dividend. For example, assume a $1 dividend has been declared on XYZ shares. Cum dividend they trade at $10 apiece and the buyer of the shares is entitled to the $1 dividend. On the ex-dividend date, the buyer loses the right to this $1 dividend and thus should be willing to offer only $9 for each share. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-10 How Dividends Are Paid • Stock Dividends vs Stock Splits A stock dividend is the distribution of additional shares, instead of cash, to the firm’s shareholders. A stock split is the issue of additional shares to a firm’s shareholders. In both cases, a shareholder is given a fixed number of new shares for each share held. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-11 How Dividends Are Paid • Stock Dividends vs Stock Splits In other words, except for minor technical details of how they are recorded on the firm’s books, a stock dividend achieves the same results as a stock split. For example, a two-for-one stock split and a 100% stock dividend both result in twice as many shares outstanding. But neither changes the assets or cash flows generated by the firm. If markets are efficient, what should happen to the stock price? copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-12 How Dividends Are Paid • Stock Dividends vs Stock Splits You should expect the stock price to fall by half, leaving the total market value of the firm (price per share x number of shares outstanding) unchanged. Often, though, the announcement of a stock split does result in a rise in the market value of the firm. This occurs even though investors know that the company’s assets and business will not be affected. Why? copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-13 How Dividends Are Paid • Stock Dividends vs Stock Splits The reason: Investors take the decision to split as a signal of management’s confidence in the company’s future prospects. They bid up the price in response to this perceived signal. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-14 How Dividends Are Paid • Stock Dividends vs Stock Splits Sometimes firms will opt for a reverse split. In a reverse split, the firm reduces the number of shares outstanding, thus increasing the price per share. For example, in a one-for-two reverse split, shareholders would exchange two existing shares for one new share. Theoretically, each share should be worth twice as much as before the reverse split. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-15 How Dividends Are Paid • Dividends vs Stock Repurchases If a firm wishes to distribute money to its shareholders, usually it would declare a cash dividend. An increasingly popular alternative is to declare a stock repurchase. In a stock repurchase, the firm buys back its shares from its shareholders. If you look at Table 16.1 on page 484 of your text, you can see that a cash dividend and a share repurchase leave a shareholder in the same financial position. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-16 How Dividends Are Paid • Dividends vs Stock Repurchases Look at panel A of Table 16.1. Assume you own 1000 shares, worth $10 each. The value of your portfolio is $10,000. Look at Panel B. Here you see the results if the firm declared a $1 per share dividend. After receiving the dividend, you still own 1000 shares, but they are now worth $9 each. However, you also have a cheque for $1,000. The value of your portfolio is thus still $10,000. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-17 How Dividends Are Paid • Dividends vs Stock Repurchases Look at panel C. Here you see the results if the firm declared a stock repurchase. After selling 100 shares back to the company, you own 900 shares, worth $10 each. However, you also received a cheque for $1,000 for the shares you sold to the firm. The value of your portfolio is thus still $10,000. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-18 The Dividend Decision • How Companies Decide on Dividend Payments How does the Board of Directors decide what type of dividend to declare? To help answer this question, John Lintner conducted a series of interviews with managers about their firm’s dividend policy. He developed four “stylized facts” which describe how dividends are determined. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-19 The Dividend Decision • Lintner’s Four Stylized Facts 1. Firms have a long run dividend payout ratio. This ratio is that fraction of earning which the company intends to pay out as dividends. 2. Managers focus on dividend changes rather than absolute levels of dividends. Paying a $2 dividend is important if last year’s dividend was $1. It is unimportant if last year’s dividend was $2. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-20 The Dividend Decision • Lintner’s Four Stylized Facts 3. Dividend changes respond to long-run sustainable changes in earnings, but not to short-run changes. Managers are unlikely to change dividends in response to temporary variations in earnings. Instead, they “smooth” dividends. 4. Managers are reluctant to make dividend changes which might have to be reversed. They are particularly worried about having to reverse a dividend increase. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-21 The Dividend Decision • The Lintner Model Managers in Lintner’s survey behaved this way because they believe that shareholders prefer a steady progression in dividends. Investors see a dividend decrease as an unfavourable signal from management about the company’s future earnings ability. In other words, investors worry that the assets will not generate enough cash flow to support the dividend. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-22 The Dividend Decision • The Lintner Model Thus, if circumstances would warrant a large increase in dividends, managers will move only partway towards their target payout. They will wait to see if the earnings increase is permanent before the dividend is fully adjusted. If you look at Figure 16.2 on page 485, you will see confirmation of Lintner’s results: While earnings fluctuate erratically, dividends are relatively stable, tracking almost a flat line. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-23 Why Dividend Policy Should Not Matter • The Irrelevancy of Dividend Policy Does it matter to the shareholders whether a firm has a policy of paying no dividends, low dividends or high dividends? This a controversial question, with three opposing beliefs: Paying a high dividend will maximize the value of the firm. Paying a low dividend will maximize the value of the firm. Dividend policy is irrelevant and cannot affect share value. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-24 Should Dividend Policy Matter? • Dividend Policy in Competitive Markets Modigliani and Miller (MM), whom we met in the last chapter, proved that under ideal conditions, capital structure is irrelevant. MM maintain that under ideal conditions, dividend policy is also irrelevant. Ideal conditions means perfect capital markets with no taxes or costs of financial distress. It also means that markets are efficient and assets are fairly priced given the information available to investors. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-25 Should Dividend Policy Matter? • Dividend Policy in Competitive Markets MM’s logic is very simple: A dividend is quite simply a way for a firm to put cash in its shareholders’ pockets. However, shareholders do not need dividends to get cash in their pocket. They can simply sell shares to get cash. Thus, rational investors will not pay higher prices for firms with higher dividend payouts. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-26 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Why Dividends May Increase the Value of the Firm Most economists believe that MM’s conclusions are correct given their assumptions of perfect and efficient capital markets. However, no one believes this is an exact description of the “real” world. Thus, the impact of dividends on firm value boils down to the effects of imperfections and inefficiencies. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-27 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Why Dividends May Increase the Value of the Firm The argument for paying higher dividends rests on their desirability to investors. For example: Some institutional investors are not allowed to hold stock if it lacks an established dividend record. Some investors (trusts, endowment funds, retirees) rely on the dividends from their portfolio to provide them with income. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-28 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Why Dividends May Increase the Value of the Firm These investors could just sell their shares to generate the cash they need, but this ignores the transactions costs and inconvenience they would incur selling a small number of shares. It is so much simpler and cheaper for the firm to simply send them a dividend cheque. Conclusion: Investors should prefer firms with higher dividends and bid up their share price. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-29 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Clientele Effect Unfortunately, life is not that simple! While it may be true that investors prefer companies paying higher dividends that doesn’t mean you can increase the value of your firm just by increasing its dividend payout. Afterall, lots of smart financial managers would have recognized this fact years ago. They would already have satisfied this clientele for high dividend stocks. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-30 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Clientele Effect You don’t hear business people saying there is a clientele for cars, so we should be manufacturing cars. They know that clientele was probably satisfied years ago. Likewise, the clientele for high dividend stocks has a wide variety of stocks to choose from. No one will notice if you add your firm to that already long list! copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-31 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Dividends as Signals Another argument for higher dividends relies on the fact that investors are constantly seeking clues as to which companies are most successful. How can an investor separate the marginally profitable companies from the real money makers? One clue they can use is dividends. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-32 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Dividends as Signals Accounting numbers may lie, but dividends require the firm to come up with hard cash. A firm that reports good earnings, but does not back it up with generous dividends may be tweaking its numbers. But a high dividend policy will be costly to firms that do not have the cash flow to support it. Thus dividend increases signal a company’s good fortune and its managers’ confidence in its future cash flows. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-33 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Information Content of Dividends Since dividends are interpreted by investors as a signal about future earnings, announcements of dividend cuts are usually taken as bad news. You should read the Finance in Action boxes on pages 492 and 493 for more details on the information content of dividends. The information content of dividends means that dividends are used as a source of information to investors about a firm’s future performance. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-34 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Why Dividends May Decrease the Value of the Firm If dividends are taxed more heavily than capital gains, then a policy of paying high dividends would hurt firm value. Investors would avoid the shares of such firms, causing their stock price to drop. Plowing earnings back into the firm, instead of declaring dividends, would produce the capital gains desired by investors. Companies with high retention rates would be rewarded by investor demand for their shares and higher share prices. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-35 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Why Pay Dividends? A look at Tax Law Implications In Chapter 2 you learned about how dividends and capital gains are taxed in Canada. Both are a tax advantaged source of income. That is, both capital gains and dividends are taxed at a lower rate than interest and other types of income. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-36 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Why Pay Dividends? A look at Tax Law Implications One of the key differences between dividends and capital gains is that taxes on dividends must be paid immediately. Taxes on capital gains are deferred until the shares are sold and the capital gains are realized. Thus, investors can control when they pay capital gains tax. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-37 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Tax Clienteles Overall, some investors in Canada are taxed more heavily on dividends, while others are taxed more heavily on capital gains. Thus, some investors have a tax reason for preferring dividends to capital gains and vice versa. Does any of these clienteles play a dominant role in the Canadian market? copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-38 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Tax Clienteles If the answer is “yes”, then we would expect that dominant clientele to have an influence on whether high-dividend yield stocks sell for more or less than low-dividend yield stocks on the basis of taxes. Unfortunately, it is difficult to measure such clientele effects and the researchers have not been able to come up with a definitive answer. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-39 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Dividend Clientele Effects Even if a clientele existed for either high- or low-dividend yield stocks, as we have already seen, most such clienteles have already been satisfied. Thus, changing your firm’s dividend policy to suit that clientele would not lead to a change in the value of your firm’s shares. That is, changing your firm’s policy would lead to a switch in investors holding your firm’s shares, but it probably would not affect your firm’s value. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-40 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Share Repurchases Instead of Cash Dividends? From a firm’s perspective a share repurchase is very similar to paying a cash dividend. However, the tax treatment for investors may be quite different. A dividend leads to an immediate tax obligation. However, an investor has the option of not tendering his/her shares to a repurchase offer and thus avoiding the capital gains tax. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-41 Seeking the Optimal Dividend Policy • Share Repurchases Instead of Cash Dividends? The authors caution financial managers from substituting share repurchases for dividends. The tax department would recognize the share repurchase for what it really is … a dividend in disguise. They would then tax the payments accordingly! This is probably why financial managers have never announced a share repurchase to save taxes. They always give another reason. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-42 Summary of Chapter 16 Dividends come in many forms, including cash dividends, stock dividends, and extra dividends. Studies have shown that managers have a target dividend payout ratio. There are also dividend-like payments such as stock splits and share repurchases. However to avoid fluctuations in dividend value, mangers smooth the dividend by moving only partway towards the target payout every year. Furthermore, managers look to future cash flows when setting the dividend. Investors know this and interpret a dividend increase as a sign of management optimism. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-43 Summary of Chapter 16 MM proved in perfect and efficient capital markets dividend policy is irrelevant. However, there is considerable controversy over the impact of dividend policy in a flawed world. Some groups hold that dividends should be high to maximize firm value. Their argument rests on the information content of such high dividends. Others hold that dividends should be low. Their argument rests on different tax treatment for dividends and capital gains. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited 15-44 Summary of Chapter 16 The dividend clientele effect argues that there may be clienteles for high (low) dividends, but that they are already satisfied. Thus changing your firm’s dividend policy may attract a new type of investor, but it will not change the value of your firm. Dividends are interpreted as a signal from management about the future prospects of the firm. If a sharp dividend change is necessary, the firm should provide as much forewarning and explanation as possible. copyright © 2003 McGraw Hill Ryerson Limited