Economic and Political Weekly

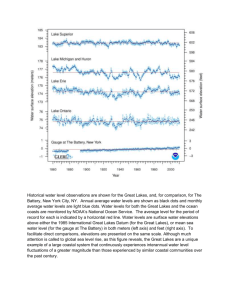

advertisement

Experiential Learning in Education Shyam Sunder December 25, 2010 I am grateful to you for assembling on this pleasant, bright, and auspicious Christmas morning. Our immediate purpose is to celebrate the opening of Great Lakes Institute’s laboratory of experiential learning with the assistance of our generous and farsighted benefactor Mr. Ramanujam at Brakes India. I would like to take these few minutes to outline its educational purpose, and to share with you the vision that energizes this experiment on the future of education in India. First, experiential learning. The ability of the Homo Sapiens to learn in several modes has allowed us dominance in many aspects of life on this earth, at least for the time being. (As you probably know, there are serious arguments for ultimate reversion of earth to insects and cockroaches because humans may fail to use their great intelligence with wisdom. But that is topic for another day. As a species, we have learned a great deal within the space of a few million years, greatly expanding our brains, ability to think, conceptualize, remember, and create new ideas, artifacts, symbols, and to process them. We have rapidly expanded our genetic endowment and passed it on through generations. This evolutionary learning is gifted to us through the genome, and we are hardly aware of this. In addition, each one of us learns a great deal more within our individual life times. In fact, our learning is so extensive that we remain dependent of our parents for some fifteen to twenty years, and in some cases, well beyond that period of physical and mental growth. This seems routine until you compare ourselves with insects, fish, snakes, dogs or cows. They complete their learning and achieve adulthood with periods ranging from a few minutes to a couple of years from their birth. 1 During this two decade long period of dependence, we learn through several ways. Most important aspects of learning are built into our genes. These include skills like walking and aspects of language. However, it is through imitation of what a baby sees in the surroundings that most learning takes place. Speech is the most striking of these attributes but there are hundreds of others. The instinct to imitate is fortunately included in our genes. The baby sees, tries to imitate, fails, adjusts, and tries again. This fundamental process of learning is far more powerful than all the teaching in this world. If babies had to depend on parents to learn to walk and talk, they would never learn. Beyond these powerful instinctive methods, human learning is supplemented by our ability to generalize through two methods: one is inference from observation and the other is logical deduction. Observation that some people who attend Great Lakes get well-paying jobs leads many others to infer that such jobs result from the attendance, and therefore attracts others interested in such jobs to this School. Finally, our faculties of logical deduction allow us to learn that the higher the income, the more a person can spend on food, clothes and housing, etc. without going into debt. Since during your 12 months at the Great Lakes the chances of your genetic evolution are low, we focus on the last three--imitation, inference and deduction—as three approaches to learning in formal education. My earliest memories of learning in the first grade was by imitation—repeating and memorizing A for apple, and counting by imitating the teacher, even before I knew what is A or what is number one. While elements of memorization are retained through all levels of education, it is not enough. Even in the elementary school, inference and deduction begin to take important roles, and must come to dominate in a good system of higher education. In secondary or higher education, a student who relies on imitation and memorization alone is at serious risk of missing on the essence of education. The traditional learning in higher education is based on reading, lectures, discussion, problem solving, laboratory and project work. These tasks combine imitation, memorization, inference, and deduction in varying degrees in an 2 attempt to exploit all our learning faculties to best advantage, and to enable us to integrate our learning in such a way that it becomes ours forever. One might forget memorized details after a few years or months, but inferences and deductions are likely to stay with us for the lifetime. The purpose of higher education is to give you learning of those elements which are important enough for you to retain through your lifetime. Since learning-by-doing is such an effective way of integrating our faculties, it is hardly surprising that laboratory method of learning has long been an integral part of education in the sciences. During the recent fifty or so years, we have developed laboratory methods of learning in social sciences such as economics and finance. During my visits to the Great Lakes during the past five or six years (and in the last two days of classes), I have introduced these methods to the Great Lakes students. When I started using and developing these methods thirty years ago, only a dozen or so people in the world know about them. Today, there over a thousand of people around the world using them. Last week I was in China to inaugurate an experimental economics laboratory at WISE institute at Xiamen University. This first Nobel Prize to an experimental economist was granted in 2003. While India has been a bit slow in adopting this method of research and learning, you should be proud to know that the Great Lakes students are the first in India to learn from these experiential methods. Last December, I addressed the first research conference in India on the subject at the University of Mumbai, and in a couple of months Economic and Political Weekly will devote a special issue to a review of experimental economics. Before I end, I would like to touch on another important issue concerning Great Lakes’ role in reshaping higher education in India, and management education in particular. Great Lakes is a wonderful visionary experiment to bring the best of higher education to India in landscape that looks quite bleak. While the enrollments grow, the quality of higher education in India is in decline. There are two primary reasons: (1) not enough talented young people (like the ones attending Great Lakes) choose a life of research, scholarship and teaching. Unless 3 the best students from the top of each year’s class choose to devote themselves to scholarship, Indian education has no future, and it will continue its rapid decline both in absolute as well as relative terms. Again, my experience in China should be an eye opener. About 90 percent of my PHD applications at Yale are from one country. Each week, I receive at least one email from a Chinese student who want to come to Yale for his PHD. During and after my visits to China, I am flooded with exceptionally talented people wanting to pursue scholarship. After my years of lecturing at Great Lakes and other Indian universities, I have yet to receive a single application from a talented student. Few application that we do receive are poor quality and have little chance of success in world wide competition. So the first thing I would like you to think about is—who would you like to teach your children? Second problem is financing. Some 16 percent of Yale’s expenses come from student fees. The rest is subsidized by donations from alumni and business community (as being done here today by Mr. Ramanujam). Nobody in the world has found a way of delivering quality education at a profit, or without large subsidies. Who will pay the money needed for quality education and research in India. Government does not have the money and will not have the money. It is for this reason that Great Lakes is a great experiment to create quality higher education at reasonable cost with the philanthropic support of those who can afford to pay. This is the public spirit that drove Tata, Birla, and many other businessmen to create schools of quality higher education in India with their philanthropy. Unless the fortunate ones among us feel an obligation to support higher education through their charity, India will not progress. When you leave Great Lakes in a few months, please do make a commitment to support the development of this and other not-for-profit schools in India. I do not mean the for-profit teaching shops that flourish in every part of India today under the guise of being not-for-profit. Your own self-interest lies in thinking long term, and provide the public good of quality higher education for all in India. But I am getting ahead of myself, because public good is the subject of tomorrow’s class and experiment. 4 Under the leadership of your founder Dr. Balachandran, your benefactor Mr. Ramanujam, your executive Director Prof. Sriram, and Mr. BalaSubramaniam who has worked tirelessly to make it possible, you are the beneficiaries of this very special opportunity to learn experientially. Perhaps, when I come here in 2011, I shall not have to distribute those slips of paper to you and collect them by hand; we might be able to do all this more easily on computers. However, I have to admit wondering if you actually enjoyed trading physically during the first day of class, and would rather not have that experience replaced by computers. I am grateful to you all for your kind attention. Merry Christmas to you all. Bharat mata ki jaya. 5