Court Briefs Barron-TLO

advertisement

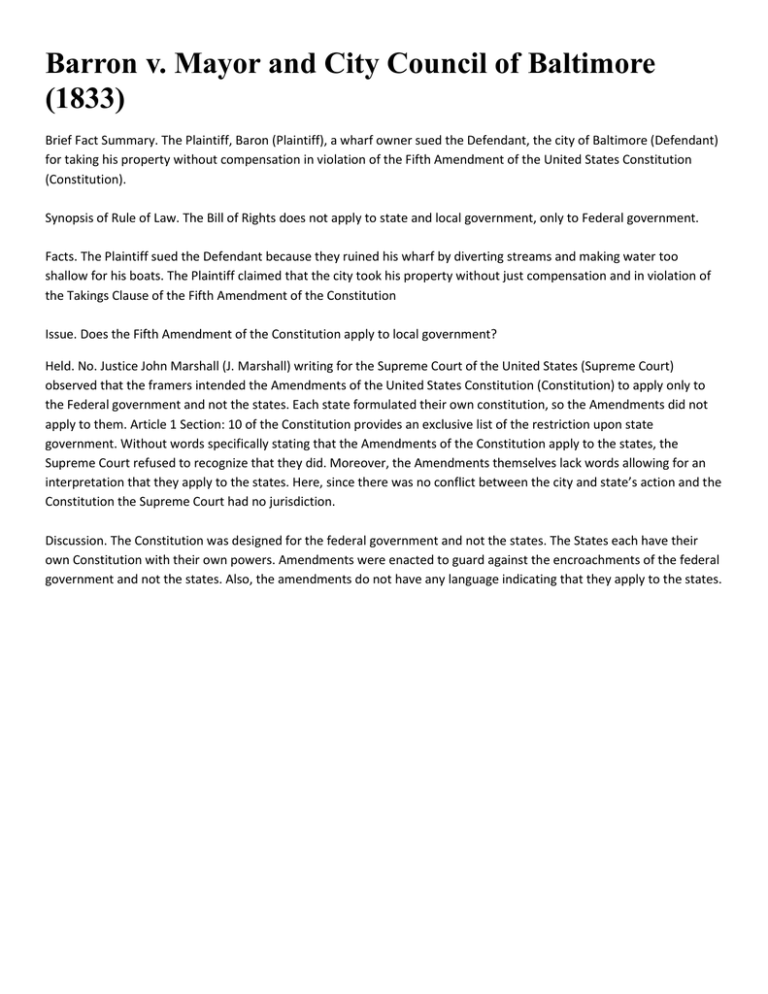

Barron v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore (1833) Brief Fact Summary. The Plaintiff, Baron (Plaintiff), a wharf owner sued the Defendant, the city of Baltimore (Defendant) for taking his property without compensation in violation of the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution (Constitution). Synopsis of Rule of Law. The Bill of Rights does not apply to state and local government, only to Federal government. Facts. The Plaintiff sued the Defendant because they ruined his wharf by diverting streams and making water too shallow for his boats. The Plaintiff claimed that the city took his property without just compensation and in violation of the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution Issue. Does the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution apply to local government? Held. No. Justice John Marshall (J. Marshall) writing for the Supreme Court of the United States (Supreme Court) observed that the framers intended the Amendments of the United States Constitution (Constitution) to apply only to the Federal government and not the states. Each state formulated their own constitution, so the Amendments did not apply to them. Article 1 Section: 10 of the Constitution provides an exclusive list of the restriction upon state government. Without words specifically stating that the Amendments of the Constitution apply to the states, the Supreme Court refused to recognize that they did. Moreover, the Amendments themselves lack words allowing for an interpretation that they apply to the states. Here, since there was no conflict between the city and state’s action and the Constitution the Supreme Court had no jurisdiction. Discussion. The Constitution was designed for the federal government and not the states. The States each have their own Constitution with their own powers. Amendments were enacted to guard against the encroachments of the federal government and not the states. Also, the amendments do not have any language indicating that they apply to the states. Gitlow v. New York (1925) Brief Fact Summary. The Petitioner, Gitlow (Petitioner), published a communist manifesto for distribution in the United States. He was charged with plotting to overthrow the United States government. Synopsis of Rule of Law. State statutes are unconstitutional if they are arbitrary and unreasonable attempts to exercise authority vested in the state to protect public interests. Facts. The Petitioner was charged with criminal anarchy because he was an advocate of socialist reform in the United States. The Petitioner is a member of the Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party. He served as the business manager for the paper that was run by the organization. In 1919 he published the group’s manifesto and prepared for widespread distribution from the New York City headquarters. Issue. Did the statute prohibiting such activity deprive the Petitioner of his First Amendment constitutional right to freedom of expression? Held. No. The current statute is not an unreasonable or arbitrary means of exercising the state’s police power. It is within the state’s power to prevent the disturbance of the peace and regulate speech that may incite crime even if the threat of such action is not immediate. Dissent. A state may not prohibit speech unless it presents a clear and present danger to the public interest. Discussion. Freedom of speech and press do not confer an absolute right to publish or speak without being held responsible for the results of such speech. The state may regulate to protect its interests in general welfare of its citizens. Mapp v. Ohio (1961) Brief Fact Summary. Police officers sought a bombing suspect and evidence of the bombing at the petitioner, Miss Mapp’s (the “petitioner”) house. After failing to gain entry on an initial visit, the officers returned with what purported to be a search warrant, forcibly entered the residence, and conducted a search in which obscene materials were discovered. The petitioner was tried and convicted for these materials. Synopsis of Rule of Law. All evidence discovered as a result of a search and seizure conducted in violation of the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution (”Constitution”) shall be inadmissible in State court proceedings. Facts. Three Cleveland police officers arrived at the petitioner’s residence pursuant to information that a bombing suspect was hiding out there and that paraphernalia regarding the bombing was hidden there. The officers knocked and asked to enter, but the petitioner refused to admit them without a search warrant after speaking with her attorney. The officers left and returned approximately three hours later with what purported to be a search warrant. When the petitioner failed to answer the door, the officers forcibly entered the residence. The petitioner’s attorney arrived and was not permitted to see the petitioner or to enter the residence. The petitioner demanded to see the search warrant and when presented, she grabbed it and placed it in her shirt. Police struggled with the petitioner and eventually recovered the warrant. The petitioner was then placed under arrest for being belligerent and taken to her bedroom on the second floor of the residence. The officers then co nducted a widespread search of the residence wherein obscene materials were found in a trunk in the basement. The petitioner was ultimately convicted of possessing these materials. Issue. Whether evidence discovered during a search and seizure conducted in violation of the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution shall be admissible in a State court? Held. Justice Tom Clark (”J. Clark”) filed the majority opinion. No, the exclusionary rule applies to evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment’s search and seizure clause in all State prosecutions. Since the Fourth Amendment’s right of privacy has been declared enforceable against the States through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the same sanction of exclusion is also enforceable against them. The purpose of the exclusionary rule is to deter illegally obtaining evidence and to compel respect for the constitutional guarantee in the only effective manner. Otherwise, a State, by admitting illegally obtained evidence, disobeys the Constitution that it has sworn to uphold. A federal prosecutor may make no use of illegally obtained evidence, but a State prosecutor across the street may, although he supposedly is operating under the enforceable prohibitions of the same Amendment. If the criminal is to go free, then it must be the law that sets him fr ee. Our government is the potent, omnipresent teacher. For good or for ill, it teaches the whole people by its example. If the government becomes a lawbreaker, it breeds contempt for law. Dissent. Justice John Harlan (”J. Harlan”) filed a dissenting opinion joined by Justice Felix Frankfurter (”J. Frankfurter”) and Justice Charles Whittaker (”J. Whittaker”). A recent study shows that one half of the States still adhere to the common-law non-exclusionary rule. The main concern is not the desirability of the rule, but whether the States should be forced to follow it. This Court should continue to forbear from fettering the States with an adamant rule which may embarrass them in coping with their own peculiar problems in criminal law enforcement. Concurrence. Justice Hugo Black (”J. Black”) filed a concurring opinion. When the Fourth Amendment’s ban against unreasonable searches and seizures is considered together with the Fifth Amendment’s ban against compelled self-incrimination, a constitutional basis emerges which not only justifies, but actually requires the exclusionary rule. Justice William Douglas (”J. Douglas”) filed a concurring opinion. He believed this to be an appropriate case in which to put an end to the asymmetry which Wolf imported into the law. Discussion. This case explicitly overrules Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U.S. 25 (1949). The federal exclusionary rule now applies to the States through application of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. All illegally obtained evidence under the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution must now be excluded. New Jersey v. TLO (1985) Brief Fact Summary. The vice-principal of a school searched a students bag and found evidence that she was dealing marijuana. Synopsis of Rule of Law. “[S]chool officials need not obtain a warrant before searching a student who is under their authority.” Facts. The principle of a high school discovered two girls smoking in a laboratory. One of the girls admitted she was smoking, which violated a school rule. The second girl claimed she was not smoking and as such did not break the rule. The assistant vice-principal took the student into his private office and demanded to search her purse. While looking for cigarettes, the vice-principal found a package of cigarette rolling papers. He continued searching the purse and found a small amount of marijuana and a pipe, a number of empty plastic bags and a substantial amount of one dollar bills and an index card with the names of various people who owed the student money. The state brought delinquency proceedings against the student and the student argued that her Fourth Amendment Rights were violated . The juvenile court denied the motion to suppress and the student was found to be delinquent. The Appellant Division affirmed the trial court’s finding there was no Fourth Amendment violation. The Supreme Court of New Jersey overruled the Appellate Division. Issue. What is the appropriate “standard for assessing the legality of searches conducted by public school officials and the application of that standard to the facts of this case[?]” Held. The search did not violate the Fourth Amendment. The majority observed, “we are faced initially with the question whether that Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures applies to searches conducted by public school officials.” The majority observed “[i]t is now beyond dispute that “the Federal Constitution, by virtue of the Fourteenth Amendment, prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures by state officers.’ ” Equally indisputable is the proposition that the Fourteenth Amendment protects the rights of students against encroachment by public school officials.” “Today’s public school officials do not merely exercise authority voluntarily conferred on them by individual parents; rather, they act in furtherance of publicly mandated educational and disciplinary policies. In carrying out searches and other disciplinary functions pursuant to such policies, school officials act as representatives of the State, not merely as surrogates for the parents, and they cannot claim the parents’ immunity from the strictures of the Fourth Amendment.” The majority then asked, “[h]ow, then, should we strike the balance between the schoolchild’s legitimate expectations of privacy and the school’s equally legitimate need to maintain an environment in which learning can take place? It is evident that the school setting requires some easing of the restrictions to which searches by public authorities are ordinarily subject. The warrant requirement, in particular, is unsuited to the school environment: requiring a teacher to obtain a warrant before searching a child suspected of an infraction of school rules (or of the criminal law) would unduly interfere with the maintenance of the swift and informal disciplinary procedures needed in the schools. Just as we have in other cases dispensed with the warrant requirement when ‘the burden of obtaining a warrant is likely to frustrate the governmental purpose behind the search, we hold today that school officials need not obtain a warrant before searching a student who is under their authority .’ ” “We join the majority of courts that have examined this issue in concluding that the accommodation of the privacy interests of schoolchildren with the substantial need of teachers and administrators for freedom to maintain order in the schools does not require strict adherence to the requirement that searches be based on probable cause to believe that the subject of the search has violated or is violating the law. Rather, the legality of a search of a student should depend simply on the reasonableness, under all the circumstances, of the search. Determining the reasonableness of any search involves a twofold inquiry: first, one must consider ‘whether the . . . action was justified at its inception,’ second, one must determine whether the search as actually conducted ‘was reasonably related in scope to the circumstances which justified the interference in the first place.’ Under ordinary circumstances, a search of a student by a teacher or other school official will be ‘justified at its inception’ when there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that the search will turn up evidence that the student has violated or is violating either the law or the rules of the school. Such a search will be permissible in its scope when the measures adopted are reasonably related to the objectives of the search and not excessively intrusive in light of the age and sex of the student and the nature of the infraction.” “This standard will, we trust, neither unduly burden the efforts of school authorities to maintain order in their schools nor authorize unrestrained intrusions upon the privacy of schoolchildren. By focusing attention on the question of reasonableness, the standard will spare teachers and school administrators the necessity of schooling themselves in the niceties of probable cause and permit them to regulate their conduct according to the dictates of reason and common sense. At the same time, the reasonableness standard should ensure that the interests of students will be invaded no more than is necessary to achieve the legitimate end of preserving order in the schools.” “Because the search resulting in the discovery of the evidence of marihuana dealing by [the second student] was reasonable, the New Jersey Supreme Court’s decision to exclude that evidence from [the student's] juvenile delinquency proceedings on Fourth Amendment grounds was erroneous. Accordingly, the judgment of the Supreme Court of New Jersey is erroneous.” Discussion. This case illustrates another instance where the warrant requirement does not apply due to the uniqueness of the situation involved. Gideon v. Wainright (1963) Brief Fact Summary. Gideon was charged with a felony in Florida state court. He appeared before the state Court, informing the Court he was indigent and requested that the Court appoint him an attorney. The Court declined to appoint Gideon an attorney, stating that under Florida law, the only time an indigent defendant is entitled to appointed counsel is when he is charged with a capital offense. Synopsis of Rule of Law. This case overruled Betts and held that the right of an indigent defendant to appointed counsel is a fundamental right, essential to a fair trial. Failure to provide an indigent defendant with an attorney is a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution (”Constitution”). Facts. Gideon was charged in a Florida state court with breaking and entering into a poolroom with the intent to commit a misdemeanor. Such an offense was a felony under Florida law. When Gideon appeared before the state Court he informed the court that he was indigent and requested the Court appoint him an attorney, asserting that “the United States Supreme Court says I am entitled to be represented by counsel.” The se Court informed Gideon that under Florida law only indigent clients charged with capital offenses are entitled to court appointed counsel. Gideon proceeded to a jury trial; made an opening statement, cross-examined the State’s witnesses, called his own witnesses, declined to testify himself; and made a closing argument. The jury returned a guilty verdict and Gideon was sentenced to serve five years in state prison. While serving his sentence, Gideon filed a petition for habeas corpus attacking his conviction and sentence on the ground that the trial court’s refusal to appoint counsel denied his constitutional rights and rights guaranteed him under the Bill of Rights. The Florida State Supreme Court denied relief. Because the problem of a defendant’s constitutional right to counsel in state court continued to be source of controversy since Betts v. Brady, the United States Supreme Court (”Supreme Court”) granted certiorari to again review the issue. Issue. Whether the Sixth Amendment constitutional requirement that indigent defendants be appointed counsel is so fundamental and essential to a fair trial that it is made obligatory on the states by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution? Held. The right to counsel is a fundamental right essential to a fair trial and due process of law. Concurrence. Justice Tom Clark (”J. Clark”) concurred and recognized that the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution clearly required appointment of counsel in “all criminal prosecutions” and that the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution requires appointment of counsel in all prosecutions for capital crimes. The instant decision does no more than erase an illogical distinction. J. Clark further concludes that the Constitution makes no distinction between capital and noncapital cases. The Fourteenth Amendment requires due process of law for the deprivation of liberty just as equally as it does for deprival of life. Accordingly, there cannot be a constitutional distinction in the quality of the process based merely upon the sanction to be imposed. Justice John Harlan (”J. Harlan”): Agrees that Betts v. Brady should be overruled, but argues that Betts recognized that there might be special circumstances in non capital cases requiring the appointment of counsel. In non capital cases the special circumstances continued to exist, but have been substantially and steadily eroded, culminating in the instant decision. J. Harlan clarified his view that he does not believe that the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution incorporates the entire Sixth Amendment resulting in all federal law applies to all the States. J. Harlan still wants to preserve to the States their independence to make law and procedures consistent with the divergent problems and legitimate interests that the States face that are difference from each other and different from the Federal Government. Discussion. The Supreme Court, in reaching its conclusion that the right to counsel is a fundamental right imposed upon the states pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, engages in an analysis of its previous decisions holding that other provisions of the Bill of Rights are fundamental rights made obligatory on the States. The Supreme Court accepts the Betts v. Brady assumption that a provision of the Bill of Rights which is fundamental and essential to a fair trial is made obligatory on the states by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. The Supreme Court diverges from Betts in concluding that the right to assistance of counsel is a fundamental right. The Supreme Court found that the Betts Court’s conclusion that assistance of counsel is not a fundamental right was an abrupt break from its own well-considered precedent. The Supreme Court further reasons that the right to be heard at trial would be, in many cases, of little avail without the assistance of counsel who is familiar with the rules of court, the rules of evidence and the general procedure of the court system. Without the assistance of counsel “though he be not guilty, he faces the danger of conviction because he does not know how to establish his innocence.” Miranda v. Arizona (1966) Brief Fact Summary. The defendants offered incriminating evidence during police interrogations without prior notification of their rights under the Fifth Amendment of the United States Constitution (the “Constitution”). Synopsis of Rule of Law. Government authorities need to inform individuals of their Fifth Amendment constitutional rights prior to an interrogation following an arrest. Facts. The Supreme Court of the United States (”Supreme Court”) consolidated four separate cases with issues regarding the admissibility of evidence obtained during police interrogations. The first Defendant, Ernesto Miranda (”Mr. Miranda”), was arrested for kidnapping and rape. Mr. Miranda was an immigrant, and although the officers did not notify Mr. Miranda of his rights, he signed a confession after two hours of investigation. The signed statement included a statement that Mr. Miranda was aware of his rights. The second Defendant, Michael Vignera (”Mr. Vignera”), was arrested for robbery. Mr. Vignera orally admitted to the robbery to the first officer after the arrest, and he was held in detention for eight hours before he made an admission to an assistant district attorney. There was no evidence that he was notified of his Fifth Amendment constitutional rights. The third Defendant, Carl Calvin Westover (”Mr. Westover”), was arrested for two robberies. Mr. Westover was questioned over fourteen hours by local police, and then was handed to Federal Bureau of Investigation (”FBI”) agents, who were able to get signed confessions from Mr. Westover. The authorities did not notify Mr. Westover of his Fifth Amendment constitutional rights. The fourth Defendant, Roy Allen Stewart (”Mr. Stewart”), was arrested, along with members of his family (although there was no evidence of any wrongdoing by his family) for a series of purse snatches. There was no evidence that Mr. Stewart was notified of his rights. After nine interrogations, Mr. Stewart admitted to the crimes. Issue. Whether the government is required to notify the arrested defendants of their Fifth Amendment constitutional rights against self-incrimination before they interrogate the defendants? Held. The government needs to notify arrested individuals of their Fifth Amendment constitutional rights, specifically: their right to remain silent; an explanation that anything they say could be used against them in court; their right to counsel; and their right to have counsel appointed to represent them if necessary. Without this notification, anything admitted by an arrestee in an interrogation will not be admissible in court. Justice Byron White (”J. White”) argued that there is no historical support for broadening the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution to include the rights that the majority extends in their decision. The majority is making new law with their holding. Discussion. The majority notes that once an individual chooses to remain silent or asks to first see an attorney, any interrogation should cease. Further, the individual has the right to stop the interrogation at any time, and the government will not be allowed to argue for an exception to the notification rule. FURMAN v. GEORGIA 1972 Facts of the Case Furman was burglarizing a private home when a family member discovered him. He attempted to flee, and in doing so tripped and fell. The gun that he was carrying went off and killed a resident of the home. He was convicted of murder and sentenced to death (Two other death penalty cases were decided along with Furman: Jackson v. Georgia and Branch v. Texas. These cases concern the constitutionality of the death sentence for rape and murder convictions, respectively). Question Does the imposition and carrying out of the death penalty in these cases constitute cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments? Decision: 5 votes for Furman, 4 vote(s) against Legal provision: Amendment 8: Cruel and Unusual Punishment Yes. The Court's one-page per curiam opinion held that the imposition of the death penalty in these cases constituted cruel and unusual punishment and violated the Constitution. In over two hundred pages of concurrence and dissents, the justices articulated their views on this controversial subject. Only Justices Brennan and Marshall believed the death penalty to be unconstitutional in all instances. Other concurrences focused on the arbitrary nature with which death sentences have been imposed, often indicating a racial bias against black defendants. The Court's decision forced states and the national legislature to rethink their statutes for capital offenses to assure that the death penalty would not be administered in a capricious or discriminatory manner. Gregg v. Georgia (1976) Brief Fact Summary. A jury imposed the death sentence on Gregg (Defendant), after finding him guilty on charges of armed robbery and murder. Synopsis of Rule of Law. Capital punishment does not violate the Eighth or Fourteenth amendments of the United States Constitution provided it is set forth in a carefully drafted statute that ensures the sentencing authority has adequate information and guidance in reaching its decision. Facts. The Supreme Court of Georgia subsequently set aside Defendant’s death sentences on the armed robbery counts, on the basis, that defendants are rarely subject to capital punishment for that crime. The Court upheld defendant’s death sentences with respect to the murder convictions. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision in the Furman case, which held a death penalty statute to be unconstitutional, because it resulted in death being imposed in an “arbitrary and capricious” manner, the Georgia legislature revised its death penalty statute so that death could only be imposed when the jury had found the presence of specific aggravating factors. This effectively narrowed the class of murderers subject to capital punishment. The new statute created ten aggravating circumstances, from which the jury would have to find the presence of at least one, in order to impose the death penalty. Held. No. Judgment affirmed. The death penalty itself is per se constitutional on several grounds. First, it does violate contemporary standards of decency insomuch as much of the country seems to have accepted it (35 states have death penalty statues); second, it serves the traditional penological justifications of both retribution and deterrence; third, it is not a disproportionate sentence to the crime of murder, but rather an extreme punishment for the most extreme of crimes. The Georgia death penalty statute does not violate the United States Constitution because it establishes a particular set of procedures to prevent the imposition of the death penalty in an arbitrary and capricious manner. By limiting the circumstances under which the death sentence could be imposed on a defendant, the statute successfully focuses the jury’s attention on the presence or absence of particular aggravating factors so as to inform their decision on whether death is an appropriate punishment in each individual case. Dissent. The penological justifications for the death penalty set forth by the majority, deterrence and retribution, are invalid. First, there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate that capital punishment is an effective deterrent to crime. Second, it is unbelievable to suggest that the imposition of life imprisonment over the death penalty would result in citizens taking the law into their own hands to carry out a death sentence. Furthermore, the Georgia death penalty statute does not provide adequate information to jurors because if the citizenry were better informed about the morality of capital punishment they would never actually impose it. Discussion. This case expanded upon the Court’s Furman decision, which had invalidated death penalty statutes all across the country. Here, the majority established that the death penalty was not per se unconstitutional; rather, states could draft statutory provisions, as Georgia had done, to guide a jury’s decision on the imposition of the death penalty. These provisions, such as a list of aggravating factors to a make a crime death-eligible, satisfied the Court that a jury’s decision to impose death in one case but not another was not entirely arbitrary.