******* 1

advertisement

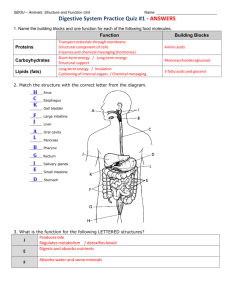

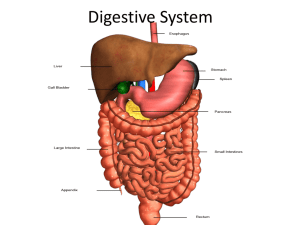

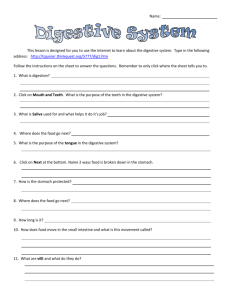

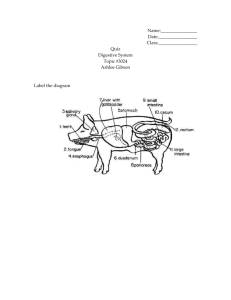

The Digestive System OVERVIEW OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM The organs of the digestive system fall into two main groups: 1- Alimentary canal, also called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or gut, It digests food—breaks it down into smaller fragments (digest = dissolved)—and absorbs the digested fragments through its lining into the blood. -The organs of the alimentary canal are the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine. -In a cadaver, the alimentary canal is approximately 9 m (about 30 ft) long, but in a living person, it is considerably shorter because of its muscle tone. . - Food material in this tube is technically outside the body because the canal is open to the external environment at both ends. 2- The accessory digestive organs are the teeth, tongue, gallbladder, and a number of large digestive glands—the salivary glands, liver, and pancreas. -The teeth and tongue are in the mouth, or oral cavity, while the digestive glands and gallbladder lie outside the GI tract and connect to it by ducts. Digestive System Organs The Mouth The mouth, a mucosa-lined cavity, is also called the oral cavity, or buccal cavity (buk′al). - Its boundaries are the lips (labia) anteriorly, cheeks laterally, palate superiorly, and tongue inferiorly . - Its anterior opening is the oral orifice. Posteriorly, the oral cavity is continuous with the oropharynx. - It is lined with stratified squamous epithelium which can withstand considerable friction. - The space bounded externally by the lips and cheeks and internally by the gums and teeth is called the vestibule . - The area that lies within the teeth and gums is the oral cavity proper. • The palate, forming the roof of the mouth, has two distinct parts: the hard palate anteriorly and the soft palate posteriorly. • The hard palate is formed by the palatine bones and the palatine processes of the maxillae, and it forms a rigid surface against which the tongue forces food during chewing. • The soft palate is a mobile fold formed mostly of skeletal muscle. Projecting downward from its free edge is the fingerlike uvula (u′vu-lah). The soft palate rises reflexively to close off the nasopharynx when we swallow. The Tongue The tongue occupies the floor of the mouth and fills most of the oral cavity when the mouth is closed. • A fold of mucosa, called the lingual frenulum, secures the tongue to the floor of the mouth and limits posterior movements of the tongue. • Children born with an extremely short lingual frenulum are often referred to as “tongue-tied” because of speech distortions that result when tongue movement is restricted. This congenital condition, called ankyloglossia (“fused tongue”), is corrected surgically by snipping the frenulum. • The Pharynx From the mouth, food passes posteriorly into the oropharynx and then the laryngopharynx ,both common passageways for food, fluids, and air. (The nasopharynx has no digestive role.) The mucosa contains a friction-resistant stratified squamous epithelium well supplied with mucus-producing glands. The Esophagus -A muscular tube about 25 cm (10 inches) long. It is collapsed when not involved in food propulsion. - Lined by stratified squamous epithelium to accommodate high friction. - It takes a fairly straight course through the mediastinum of the thorax and pierces the diaphragm at the esophageal hiatus to enter the abdomen. -It joins the stomach at the cardiac orifice. The cardiac orifice is surrounded by the gastro-esophageal or cardiac sphincter acts as a valve. -The muscular diaphragm, which surrounds this sphincter, helps keep it closed when food is not being swallowed. Histology of the Alimentary Canal From the esophagus to the anal canal, the walls of the alimentary canal have the same four basic layers : 1-The mucosa, or mucous membrane—the innermost layer—is a moist epithelial membrane that lines the alimentary canal lumen from mouth to anus. Its major functions are (1) secretion of mucus, digestive enzymes, and hormones, (2) absorption of the end products of digestion into the blood, and (3) protection against infectious disease. 2- The Submucosa just external to the mucosa, is a moderately dense connective tissue containing blood and lymphatic vessels, lymphoid follicles, and nerve fibers. 3-The Muscularis Externa This layer is responsible for segmentation and peristalsis. It typically has an inner circular layer and an outer longitudinal layer of smooth muscle cells .In several places along the tract, the circular layer thickens, forming sphincters that act as valves to prevent backflow and control food passage from one organ to the next. 4-The Serosa The outermost layer which is the visceral peritoneum. It is formed of a single layer of squamous epithelial cells. HOMEOSTATIC IMBALANCE Heartburn, the first symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), is the burning, radiating substernal pain that occurs when the acidic gastric juice regurgitates into the esophagus. Heartburn is most likely to happen in conditions that force abdominal contents superiorly, such as extreme obesity, pregnancy, and running, which causes stomach contents to splash upward with each step (runner’s reflux). It is also common in those with a hiatal hernia, in which the superior part of the stomach protrudes slightly above the diaphragm. If the episodes are frequent and prolonged, esophagitis (inflammation of the esophagus) and esophageal ulcers may result. • The Stomach A temporary “storage tank” where chemical breakdown of proteins begins and food is converted to a creamy paste called chyme (kīm; “juice”). • The stomach lies in the upper left quadrant of the peritoneal cavity, nearly hidden by the liver and diaphragm. • An empty stomach has a volume of about 50 ml but it can hold about 4 L of food and may extend nearly to the pelvis! • When empty, the stomach collapses inward, throwing its mucosa (and submucosa) into large, longitudinal folds called rugae . • The small cardiac region, or cardia (“near the heart”), surrounds the cardiac orifice through which food enters the stomach from the esophagus. • The fundus is its dome-shaped part, that bulges superolaterally to the cardia. • The body, the midportion of the stomach, is continuous inferiorly with the funnel-shaped pyloric region. The pylorus is continuous with the duodenum through the pyloric sphincter, which controls stomach emptying . • The convex lateral surface of the stomach is its greater curvature, and its concave medial surface is the lesser curvature. • The lesser omentum runs from the liver to the lesser curvature of the stomach, where it becomes continuous with the visceral peritoneum covering the stomach. • The greater omentum from the greater curvature of the stomach to cover the coils of the small intestine. The greater omentum is riddled with fat deposits. It also contains large collections of lymph nodes. • Microscopic Anatomy of the stomach -Besides the usual circular and longitudinal layers of smooth muscle, there is a layer that runs obliquely . -The lining epithelium of the stomach mucosa is a simple columnar epithelium composed entirely of goblet cells, which produce a protective coat of alkaline mucus .There are millions of gastric glands that produce the stomach secretion called gastric juice. The glands contain four types of cells: 1. Mucous neck cells, found in the upper, or “neck,” regions of the glands, produce mucus . 2. Parietal cells, secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl) and intrinsic factor. -HCl makes the stomach contents extremely acidic (pH 1.5–3.5), a condition necessary for activation and optimal activity of pepsin enzyme. The acidity can kill many of the bacteria ingested with foods. - Intrinsic factor is a glycoprotein required for vitamin B12 absorption in the small intestine. 3. Chief cells produce pepsinogen (pep-sin′o-jen), the inactive form of the protein-digesting enzyme pepsin. 4. Enteroendocrine cells release a variety of chemical messengers. Some of these, for example histamine and serotonin, act locally. Others, such as somatostatin, act both locally and as hormones -Gastrin, a hormone, plays essential roles in regulating stomach secretion and motility. The Small Intestine -Is a convoluted tube extending from the pyloric sphincter in the epigastric region to the ileocecal valve in the right iliac region where it joins the large intestine -It is the longest part of the alimentary tube. It is 6– 7 m long in a cadaver, but is only about 2–4 m long during life because of muscle tone. -Within its twisted passageways, digestion is completed and virtually all absorption occurs. The small intestine has three subdivisions: • the duodenum, is relatively immovable “twelve finger widths long”, which curves around the head of the pancreas ,is about 25 cm (10 inches) long. -The bile duct and the main pancreatic duct unite in the wall of the duodenum in the hepatopancreatic ampulla . The ampulla opens into the duodenum and is controlled by a muscular valve called the hepatopancreatic sphincter, or sphincter of Oddi. • The jejunum ,about 2.5 m (8 ft) long, extends from the duodenum to the ileum. • The ileum ,approximately 3.6 m (12 ft) in length, joins the large intestine at the ileocecal valve. The jejunum and ileum are suspended from the posterior abdominal wall by the fan-shaped mesentery . • They are encircled and framed by the large intestine. • The nutrient-rich venous blood from the small intestine drains into the hepatic portal vein, which carries it to the liver. • Modifications for Absorption : - Its length - The circular folds, or plicae circulares are deep, permanent folds of the mucosa and submucosa . Nearly 1 cm tall, these folds force chyme to spiral through the lumen, slowing its movement and allowing time for full nutrient absorption. -Villi are fingerlike projections of the mucosa .In the core of each villus is a dense capillary bed and a wide lymph capillary called a lacteal . - Microvilli, tiny projections give the mucosal surface an appearance called the brush border .The plasma membranes of the microvilli bear enzymes referred to as brush border enzymes, which complete the digestion of carbohydrates and proteins in the small intestine. The Large Intestine -The large intestine frames the small intestine on three sides and extends from the ileocecal valve to the anus. Its diameter, at about 7 cm( nearly double the small intestine (hence, large intestine), but it is less than half as long (1.5 m versus 6 m). -Its major function is to absorb most of the remaining water from indigestible food residues (delivered to it in a fluid state), store the residues temporarily, and then eliminate them from the body as semisolid feces (fe′sēz). • Gross Anatomy -The large intestine has two features not seen elsewhere : -the longitudinal muscle layer is reduced to three bands of smooth muscle called teniae coli . -Their tone causes the wall of the large intestine to pucker into pocketlike sacs called haustra . -The large intestine has the following subdivisions: 1-The saclike cecum which lies below the ileocecal valve in the right iliac fossa. 2-The blind, wormlike vermiform appendix. The appendix contains masses of lymphoid tissue, and as part of MALT. 3- The colon has several distinct regions: -the ascending colon -it makes a right-angle turn—the right colic, or hepatic, flexure—and travels across the abdominal cavity as the transverse colon. -Directly anterior to the spleen, it bends acutely at the left colic (splenic) flexure and descends down the left side of the abdominal wall as the descending colon. -Inferiorly, it enters the pelvis, where it becomes the Sshaped sigmoid colon. 4- In the pelvis, the sigmoid colon joins the rectum, which runs just in front of the sacrum. The position of the rectum allows the prostate gland of males to be examined digitally (with a finger) through the anterior rectal wall. This is called a rectal exam. 5-The anal canal is about 3 cm long, it opens to the body exterior at the anus. The anal canal has two sphincters: a- an involuntary internal anal sphincter composed of smooth muscle and b-a voluntary external anal sphincter composed of skeletal muscle. The sphincters, are ordinarily closed except during defecation. Accessory Digestive organs • The Teeth Teeth are classified according to their shape and function as incisors, canines, premolars, and molars . Ordinarily by age 21, two sets of teeth: - The primary dentition consists of the deciduous teeth, also called milk or baby teeth. The first teeth to appear, at about age 6 months, are the lower central incisors. Additional pairs of teeth erupt at one- to two-month intervals until about 24 months, when all 20 milk teeth have emerged. - As the deep-lying permanent teeth enlarge the mil; teeth loosen and fall out between the ages of 6 and 12 years. Generally, all the teeth of the permanent dentition (but the third molars) have erupted by the end of adolescence. -The third molars, also called wisdom teeth, emerge between the ages of 17 and 25 years. There are usually 32 permanent teeth in a full set, but sometimes the wisdom teeth are completely absent. • Tooth Structure Each tooth has two major regions: the crown and the root . -The enamel-covered crown is the exposed part of the tooth above the gingiva or gum, which surrounds the tooth like a tight collar. Enamel, an acellular, brittle material that directly bears the force of chewing, is the hardest substance in the body. • The crown and root are connected by a constricted tooth region called the neck. • The outer surface of the root is covered by cementum, a calcified connective tissue, which attaches the tooth to the thin periodontal ligament . • Dentin, a bonelike material, underlies the enamel cap and forms the bulk of a tooth. It surrounds a central pulp cavity containing a number of soft tissue structures (connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerve fibers) collectively called pulp. Pulp supplies nutrients to the tooth tissues and provides for tooth sensation. • Where the pulp cavity extends into the root, it becomes the root canal. At the proximal end of each root canal is an apical foramen that allows blood vessels, nerves, and other structures to enter the pulp cavity. • The Salivary Glands A number of glands associated with the oral cavity secrete saliva which. (1) cleanses the mouth, (2) dissolves food chemicals so that they can be tasted, (3) moistens food and aids in compacting it into a bolus, and (4) contains enzymes that begin the chemical breakdown of starchy foods. Three pairs of salivary glands: 1-The large parotid gland lies anterior to the ear. The prominent parotid duct opens into the vestibule next to the second upper molar. Branches of the facial nerve run through the parotid gland on their way to the muscles of facial expression. For this reason, surgery on this gland can result in facial paralysis. • HOMEOSTATIC IMBALANCE Mumps, a common children’s disease, is an inflammation of the parotid glands caused by the mumps virus (myxovirus), which spreads from person to person in saliva. People with mumps complain of pain when they open their mouth or chew. Mumps in adult males carry a 25% risk that the testes may become infected as well, leading to sterility. 2- the submandibular gland lies along the medial aspect of the mandibular body. 3- The small sublingual gland lies under the tongue and opens via 10–12 ducts into the floor of the mouth. To a greater or lesser degree, the salivary glands are composed of two types of secretory cells: mucous and serous. Serous cells produce a watery secretion containing enzymes and ions, whereas the mucous cells produce mucus. • Composition of Saliva -water—97 to 99.5%.. - slightly acidic (pH 6.75 to 7.00). - Its solutes include electrolytes (Na+, K+, Cl–, PO4–, and HCO3–); the digestive enzyme salivary amylase; the proteins mucin (mu′sin), lysozyme, and IgA; and metabolic wastes (urea and uric acid). When dissolved in water, the glycoprotein mucin forms thick mucus that lubricates the oral cavity and hydrates foodstuffs. • The Pancreas The pancreas is a soft gland that extends across the abdomen from its tail (abutting the spleen) to its head, which is encircled by the C-shaped duodenum . Most of the pancreas is retroperitoneal and lies deep to the greater curvature of the stomach. -It produces enzymes that break down all categories of foodstuffs. -Pancreatic islets (islets of Langerhans) are miniendocrine glands release insulin and glucagon, hormones that play an important role in carbohydrate metabolism . • Composition of Pancreatic Juice -Approximately 1200 to 1500 ml is produced daily. -The high pH (about pH 8)of pancreatic fluid helps neutralize acid chyme and provides the optimal environment for activity of intestinal and pancreatic enzymes. -Trypsin, and chymotrypsin . -Amylase -lipases, and -nucleases. • The Liver and Gallbladder The liver and gallbladder are accessory organs associated with the small intestine. The liver, one of the body’s most important organs, has many metabolic and regulatory roles. However, its digestive function is to produce bile for export to the duodenum. Bile is a fat emulsifier; that is, it breaks up fats into tiny particles so that they are more accessible to digestive enzymes. The gallbladder is chiefly a storage organ for bile. • Gross Anatomy of the Liver The liver is the largest gland in the body, weighing about 1.4 kg .Located under the diaphragm, the liver lies almost entirely within the rib cage, which provides some protection . - The liver is said to have four primary lobes. The largest of these is the right lobe. -Bile leaves the liver through several bile ducts that ultimately fuse to form the large common hepatic duct, which travels downward toward the duodenum. Along its course, that duct fuses with the cystic duct draining the gallbladder to form the bile duct . Composition of Bile -A yellow-green, alkaline solution containing bile salts, bile pigments, cholesterol, triglycerides, phospholipids (lecithin and others), and a variety of electrolytes. -Of these, only bile salts and phospholipids aid the digestive process. Bile salts are cholesterol derivatives. Their role is to emulsify fats .As a result, large fat globules entering the small intestine are physically separated into millions of small, more accessible fatty droplets that provide large surface areas for the fat-digesting enzymes to work on. • The chief bile pigment is bilirubin a waste product of the heme of hemoglobin formed during the breakdown of worn-out erythrocytes • The liver produces 500 to 1000 ml of bile daily, and production increases when the GI tract contains fatty chyme . The gallbladder is a thin-walled green muscular sac about 10 cm long in a shallow fossa on the ventral surface of the liver . - The gallbladder stores and concentrates bile by absorbing some of its water and ions. (In some cases, bile released from the gallbladder is ten times as concentrated as that entering it.) -When its muscular wall contracts, bile is expelled into its duct, the cystic duct, and then flows into the bile duct. • HOMEOSTATIC IMBALANCE Bile is the major vehicle for cholesterol excretion, and bile salts keep the cholesterol dissolved within bile. Too much cholesterol or too few bile salts leads to cholesterol crystallization, forming gallstones, or biliary calculi which obstruct the flow of bile. When the gallbladder is removed, the bile duct enlarges to assume the bile-storing role. Bile duct blockage prevents both bile salts and bile pigments from entering the intestine. As a result, yellow bile pigments accumulate in blood and eventually are deposited in the skin, causing obstructive jaundice . Digestive Processes The processing of food by the digestive system involves six essential activities: 1. Ingestion is simply taking food into the digestive tract, usually via the mouth. 2. Propulsion, which moves food through the alimentary canal, includes : -swallowing, which is initiated voluntarily, and - peristalsis ,an involuntary process. the major means of propulsion, involves alternate waves of contraction and relaxation of muscles in the organ walls .Its main effect is to squeeze food along the tract, but some mixing occurs as well. In fact, peristaltic waves are so powerful that, once swallowed, food and fluids will reach your stomach even if you stand on your head. 3. Mechanical digestion Mechanical processes include chewing, mixing of food with saliva by the tongue, churning food in the stomach, and segmentation, or rhythmic local constrictions of the intestine Segmentation mixes food with digestive juices. 4. Chemical digestion is a series of steps in which complex food molecules are broken down to their chemical building blocks by enzymes secreted into the lumen of the alimentary canal. Chemical digestion of foodstuffs begins in the mouth and is essentially complete in the small intestine. 5. Absorption is the passage of digested end products through the mucosal cells by active or passive transport into the blood or lymph. The small intestine is the major absorptive site. 6. Defecation eliminates indigestible substances from the body via the anus in the form of feces. METABOLISM The term metabolism encompasses all of the reactions that take place in the body .It is divided into : 1-Anabolism:means synthesis or “formation of larger molecules. Such reactions require energy, usually in the form of ATP. 2- Catabolism means decomposition, the breaking of bonds of larger molecules to form smaller ones. -Most of our anabolic and catabolic reactions are catalyzed by enzymes. Enzymes are proteins that enable reactions to take place rapidly at body temperature. The body has thousands of enzymes, and each is specific, that is, will catalyze only one type of reaction. Carbohydrate Metabolism -all food carbohydrates are eventually transformed to glucose -Glucose enters the tissue cells by facilitated diffusion, a process that is greatly enhanced by insulin.Cellular respiration is the sourse of ATP - Glucose is needed for the synthesis of the pentose Sugars(ribose) found in DNA and RNA. • Any glucose in excess of immediate energy needs or the need for pentose sugars is converted to glycogen in the liver and skeletal muscles. • Glycogen is then an energy source during states of hypoglycemia or during exercise. • If still more glucose is present, it will be changed to fat and stored in adipose tissue(lipogenesis). • Gluconeogenesis is the formation of glucose from noncarbohydrate (fat or protein) molecules. It occurs in the liver when blood glucose levels begin to fall. Proteins Metabolism Amino acids are the structural building blocks of the body. • Animal products provide high-quality complete protein containing all (10) essential amino acids. • Most plant products lack one or more of the essential amino acids. • Protein synthesis can and will occur if all essential amino acids are present .Otherwise, amino acids will be burned for energy. • A dietary intake of 0.8 g of protein per kg of body weight is recommended for most healthy adults. - Excess amino acids; will be deaminated and converted to simple carbohydrates or they may be changed to fat and stored in adipose tissue. -Amine groups removed during deamination (as ammonia) are combined with carbon dioxide by the liver to form urea. Urea is excreted in urine. -Protein synthesis requires the presence of all ten essential amino acids. If any are lacking, amino acids are used as energy fuels. Lipids Metabolism • Most dietary lipids are triglycerides. The primary sources of saturated fats are animal products while unsaturated fats are present in plant products, nuts, and fish. • The major sources of cholesterol are egg yolk, meats, and milk products . • Linoleic and linolenic acids are essential fatty acids. -Triglycerides provide reserve energy, cushion body organs, and insulate the body. -Phospholipids are used to synthesize plasma membranes and myelin. -Cholesterol is used in plasma membranes and is the structural basis of vitamin D, steroid hormones, and bile salts. -Fat intake should represent 35% or less of caloric intake. - About 15% of blood cholesterol comes from the diet. The other 85% is made from by the liver. Cholesterol is never used as an energy source. -The end products of fat digestion that are not needed immediately for energy production may be stored as fat (triglycerides) in adipose tissue. Most adipose tissue is found subcutaneously and is potential energy for times when food intake decreases. • Cholesterol Transport Because fats are insoluble in water, they are transported to and from tissue cells bound to small lipid-protein complexes, formed by the liver, called lipoproteins. In general, the higher the percentage of lipid in the lipoprotein, the lower its density; and the greater the proportion of protein, the higher its density. On this basis, there are high-density lipoproteins (HDLs), low-density lipoproteins (LDLs), and very low density lipoproteins (VLDLs). • LDLs transport triglycerides and cholesterol from the liver to the tissues, whereas HDLs transport cholesterol from the tissues to the liver (for catabolism and elimination). Excessively high LDL levels are implicated in atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, and strokes. • The Metabolic Role of the Liver 1-The liver is the body’s main metabolic organ and it plays a crucial role in processing (or storing) virtually every nutrient group. 2-It helps maintain blood energy sources, metabolizes hormones, and detoxifies drugs and other substances. 3-The liver synthesizes cholesterol, catabolizes cholesterol and secretes it in the form of bile salts, and makes lipoproteins. METABOLIC RATE The metabolic rate is usually expressed as an amount of heat production. -The energy required for merely living (lying quietly in bed) is the basal metabolic rate (BMR) -Total Metabolic Rate(TMR):the amount of energy actually expended during an average day (24 hours). To estimate your own basal metabolic rate (BMR): -For women: use the factor of 0.9 kcal / kg/hour. -For men: use the factor of 1.0 kcal / kg /hour Then multiply kcal/hour by 24 hours . Example: A 55 kg- woman: 1. Multiply kg weight by the BMR factor: 55 kg x 0.9 kcal/kg/hr = 49.5 kcal/hr 2. Multiply kcal/hr by 24: 49.5 kcal/hr x 24 = 1188 kcal/day (An approximate BMR, about 1200 kcal/day). Example: A 70 kg - man: 1. 70 kg x 1.0 kcal/kg/hr = 70 kcal/hr 3. 70 kcal/hr x 24 = 1680 kcal/day (An approximate BMR, about 1700 kcal/day). To approximate, the TMR the following percentages may be used: -Sedentary activity: add 40% to 50% of the BMR to the BMR -Light activity: add 50% to 65% of the BMR to the BMR -Moderate activity: add 65% to 75% of the BMR to the BMR -Strenuous activity: add 75% to100% of the BMR to the BMR Body Temperature - Normal range is 36° to 38°C with an average of 37°C. - Temperature regulation in infants and the elderly is not as precise as it is at other ages. Heat Production Heat is one of the energy products of cell respiration. Many factors affect the total heat actually produced: 1. Thyroxine from the thyroid gland—the most important regulator of daily heat production. As metabolic rate decreases, more thyroxine is secreted to increase the rate of cell respiration. 2. Stress—sympathetic impulses and epinephrine and norepinephrine increase the metabolic activity of many organs, increasing the production of ATP and heat. 3. Active organs continuously produce heat. Skeletal muscle tone produces 25% of the total body heat at rest. The liver provides up to 20% of the resting body heat. 4. Food intake increases the activity of the digestive organs and increases heat production. 5. Changes in body temperature affect metabolic rate. A fever increases the metabolic rate, and more heat is produced. Heat Loss 1. Most heat is lost through the skin. 2. Blood flow through the dermis determines the amount of heat that is lost by radiation, conduction, and convection. 3. Vasodilation in the dermis increases blood flow and heat loss; radiation and conduction are effective only if the environment is cooler than the body. 4. Vasoconstriction in the dermis decreases blood flow and conserves heat in the core of the body. 5. Sweating is a very effective heat loss mechanism; excess body heat evaporates sweat on the skin surface; sweating is most effective when the atmospheric humidity is low. 6. Heat is lost from the respiratory tract by the evaporation of water from the warm respiratory mucosa; water vapor is part of exhaled air. 7. A very small amount of heat is lost as urine and feces are excreted at body temperature. Regulation of Heat Loss 1. The hypothalamus is the thermostat of the body and regulates body temperature by balancing heat production and heat loss . It receives information from its own neurons and from the temperature receptors in the dermis. Fever—is controlled hyperthermia. Most often, it results from infection somewhere in the body, but it may be caused by cancer or allergic reactions. 1. Pyrogens are substances that cause a fever: bacteria, foreign proteins, or chemicals released during inflammation (endogenous pyrogens). 2. Pyrogens raise the setting of the hypothalamic thermostat; the person feels cold and begins to shiver to produce heat. 3. When the pyrogen has been eliminated, the hypothalamic setting returns to normal; the person feels warm, and sweating begins to lose heat to lower the body temperature. -A low fever may be beneficial because it increases the activity of WBCs and inhibits the activity of some pathogens. -A high fever may be detrimental because enzymes are denatured at high temperatures. This is most critical in the brain, where cells that die cannot be replaced. Heat-Promoting Mechanisms When the external temperature is low or blood temperature falls for any reason, the following mechanisms help: 1-Constriction of cutaneous blood vessels. As a result, blood is restricted to deep body areas and largely bypasses the skin. HOMEOSTATIC IMBALANCE Restricting blood flow to the skin is not a problem for a brief period, but if it is extended (as during prolonged exposure to very cold weather), skin cells deprived of oxygen and nutrients begin to die. This extremely serious condition is called frostbite. 2. Shivering. is involuntary shuddering contractions. Shivering is very effective in increasing body temperature because muscle activity produces large amounts of heat. 3. Enhanced thyroxine release. Because thyroid hormone increases metabolic rate, body heat production increases. 4. Some behavioral modifications : -Putting on more or warmer clothing. -Drinking hot fluids -Increasing physical activity (jumping up and down, clapping the hands). Heat-Loss Mechanisms Most heat loss occurs through the skin via radiation, conduction, convection, and evaporation. Heat-loss mechanisms include : 1. Dilation of cutaneous blood vessels. 2. Enhanced sweating. 3. Some behavioral modifications: • Reducing activity (“laying low”) • Seeking a cooler environment (a shady spot) or using a device to increase convection (a fan or air conditioner) • Wearing light-colored, loose clothing that reflects radiant energy. (This is actually cooler than being nude because bare skin absorbs most of the radiant energy striking it.) • HOMEOSTATIC IMBALANCE -Under conditions of overexposure to a hot and humid environment, normal heat-loss processes become ineffective. The skin becomes hot and dry and multiple organ damage becomes a distinct possibility, including brain damage. This condition, called heat stroke, can be fatal unless corrective measures are initiated immediately (immersing the body in cool water and administering fluids). • HOMEOSTATIC IMBALANCE Hypothermia (hi″po-ther′me-ah) is low body temperature resulting from prolonged uncontrolled exposure to cold. Vital signs (respiratory rate, blood pressure, and heart rate) decrease as cellular enzymes become sluggish. Shivering stops at a core temperature of 30–32°C (87–90°F) when the body has exhausted its heatgenerating capabilities. Uncorrected, the situation progresses to coma and finally death (by cardiac arrest), when body temperatures approach 21°C (70°F). Developmental Aspects of the Digestive System 1. Important congenital abnormalities of the digestive tract include cleft palate/lip, tracheoesophageal fistula, and cystic fibrosis. All interfere with normal nutrition. 2-The efficiency of all digestive system processes declines in the elderly. Fecal incontinence, and GI tract cancers such as stomach and colon cancer appear with increasing frequency in an aging population.