The History of the Normative Opposition of *Language versus

advertisement

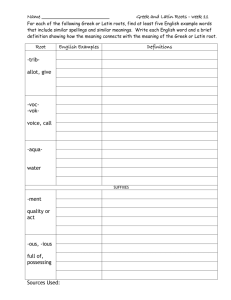

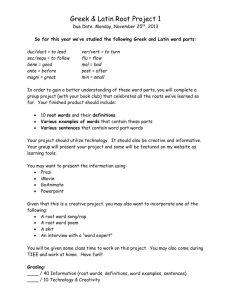

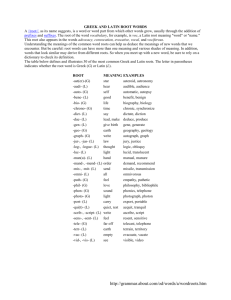

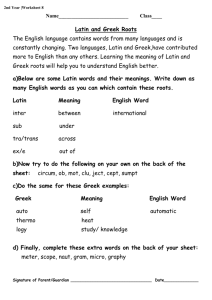

Ludwig Boltzmann Institut, Innsbruck Neulateinische Studien Conference Latin, National Identity and the Language Question in Central Europe Panel: Language and Identity I; Thur, Dec 13, 2012, 9:00-10:45 The History of the Normative Opposition of ‘Language versus Dialect:’ From Its Graeco-Latin Origin to Central Europe's Ethnolinguistic Nation-States Tomasz Kamusella University of St Andrews Scotland, UK Received Believes in the West: Languages and Dialects • Belief 1: there are languages and dialects • Belief 2: dialects are qualitatively different from languages • Belief 3: dialects belong to appropriate languages • Secondary belief A: different peoples / nations speak & write different languages • Secondary belief B: groups speaking dialects are parts of peoples / nations that speak and write languages Received Believes and Linguists • Desire for making linguistics into a natural science • Leonard Bloomfield. 1926. A Set of Postulates for the Science of Language. Language. Vol 2. • Bloomfield’s proposition: Languages are mutually unintelligible, dialects (of a language) are mutually comprehensible • Problem 1: Dialects of Arabic or Chinese are often mutually incomprehensible • Problem 2: The languages of Moldovan & Romanian or Bulgarian & Macedonian are almost exactly the same, and thus fully mutually comprehensible • Problem 3: Asymmetrical in/comprehensibility in Spanish/Portuguese or among Scandinavia’s Germanic languages • Ergo, no linguistic definition of the language vs dialect opposition • Hence, its origin and functioning must lie in extralinguistic factors, that is, human decisions and choices, in the vagaries of human culture and its changes Ancient Greek: Glossa • 8th c BCE: the organ (muscle) of the ‘tongue’ • 5th c BCE: a language or dialect (that is, a lect) • 3rd c BCE: peoples speaking different languages, ergo a people = a language Ancient Greek: Dialektos Writing and Glossa • Early 4th c BCE: Dialektos - ‘discourse’ or ‘conversation,’ especially in the context of learned discussions conducted among philosophers and scholars (thence the philosophical term ‘dialectics’) • Mid-4th c BCE: Dialektos - ‘speech,’ ‘language,’ and ‘common language’ • 2nd c BCE: Dialektos - ‘a language of a country,’ thus becoming quite synonymous with Glossa in the meaning of ‘a people living in a country’ • Late 1st c BCE: Dialektos denotes ‘a spoken language,’ as opposed to ‘a written language,’ • that is, Glossa meaning ‘written language’ • Emergence of the opposition Dialektos vs Glossa = oral vs written Latin-Greek Bilingualism • Early 2nd c BCE: Lingua ‘the organ of tongue’ and ‘the particular mode of speech in a given country or region.’ (These meanings corresponded closely to those of the Greek glossa) • (Late 2nd c BCE glossa was marginalized in Latin as a term for ‘a collection of unfamiliar words’ (that is, a ‘glossary’). And the neologism glossema was coined for ‘an unusual word requiring explanation’) • 30s of 1st c BCE the Greek loanword dialectos was attested in Latin for ‘a dialect, a form of speech [hence, unwritten]’ (Glare 1982, 536) • Hence, the Greek distinction between ‘spoken language’ (dialektos) and ‘written language’ (glossa) was adopted in Latin as: Dialectos vs Lingua. • 1st – 2nd cc CE: the Greek opposition dialektos vs glossa was consolidated in the Greek texts of the time that frequently were translated into Latin fortifying the Latin opposition Dialectos vs Lingua • • • • • • In the Christian West Translatio imperii and ‘Translatio lingua’ ? > Transmission of concepts from the bilingual, Latin-Greek Antiquity to the Christian West > 1st c CE: the Greek original of the New Testament; late 2nd c CE: Latin translation of the New Testament; early 5th c CE: the consolidation of the new world view in the Vulgate, or canonical Latin translation of the Bible. M(edieval) Latin: the rise of the term Natio - ‘people,’ ‘race’ (today, we’d say ‘ethnic group’), ‘set of people,’ ‘the people of a country, or state’ ‘a region of a country, occupied by a people.’ M Latin: the decline of the term Gens, which was a near-synonym of Natio M Latin: Lingua - a close association with Natio / Gens, following the former word’s 2nd c BCE meaning ‘the particular mode of speech in a given country or region,’ in turn, a reflection of the 3rd BCE meaning of the Greek word Glossa for ‘a people living in a country’ M Latin: Dialectos disappeared and replaced with the neologism Linguagium for ‘an unwritten form of speech’ Oppostion between written and unwritten lects also mapped by opposing Latin to ‘Vulgar Latin’ (Latinum Vulgare) or ‘Countryside Latin’ (Lingua Romana Rustica) The Counter/Reformation: From Vernaculars to Written Languages • Translating the Vulgate into vernaculars: recreating the Western Christian cultural package in a plethora of initially unwritten forms of speech, thus made into languages in their own right • Vernaculars opposed to Latin (Greek) • Early 17th c: English ‘Vernacular’ (from Latin Vernaculus for ‘domestic,’ ‘native,’ ‘indigenous’) for the ‘speech of the people of a particular country or district;’ later ‘a written language developed on the basis of this speech’ • Likewise, the ancient opposition between ‘spoken lect’ and ‘written lect’ revived (Dialektos vs Glossa; Dialectos vs Lingua) • The term Linguagium disappears • 1570s: In English (directly from classical Latin or via French) the term ‘Dialect’ is revived for denoting ‘a subordinate form of a language, a manner of speech peculiar to a group of people’ From the Territorial State to the Nation • 15th-17th c religious wars, compromise > eius regio cuius religio, hence one polity – one religion, the political principle of religious homogeneity • The population of a polity are generically referred to as a Natio > Italian nazione (1294) , German Nation (14th c), Slavic narod (14th c) Spanish nación (1444), Polish nacja (1558), English nation (1600, 14th c in form nacioun), Portuguese naçao (1691; 14th c in forms naçõ, nasçião), Russian natsiia (1705) • 18th c, new theory (Nationalism): each nation (‘group of people,’ however defined) should live in its own state (that is, nation-state) not shared with any other nation or controlled by a nation-state of another nation • Turn of the 19th c: Herder, Hegel, Napoleonic Wars, the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, the rise of ethnolinguistic nationalism > language = nation = state (eius regio cuius lingua) The normative Politicization of the Dialect vs Language Opposition • Language – written lect, defined as the national language of a nation, and official in a (nation-)state • Dialect – oral (unwritten) lect, typically subsumed under the ‘umbrella’ of an extant recognized national / official language • 19th c – mid-20th c: Spread of full literacy and ethnolinguistic nationalism across Europe • Often, when a dialect gets written it is not recognized as a language, because it would necessitate the creation of a new state for the speakers of this dialect-turnedlanguage, hence construed as a nation Humans: Main Extralinguistic Force Dilemma: How to keep the number of the nation-states low and not to fall foul of the requirements of ethnolinguistic nationalism? Some tried solutions • written or not dialect remain dialects (Low German in Germany), • or autonomous regions / separate states created for the speakers of such dialects-turned-languages (Croatia), • or in multilingual aspiring nation-states amalgam languages are postulated/created (German, Serbocroatoslovenian, Czechoslovak), • or the same language goes by two different names to serve appropriately separate nation-states (Moldovan/Romanian, Bulgarian/Macedonian), • or languages are created/proclaimed for separate states that share the same language (Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, Serbian)