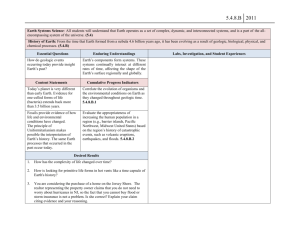

Section 1 Geologic History Chapter 5

advertisement

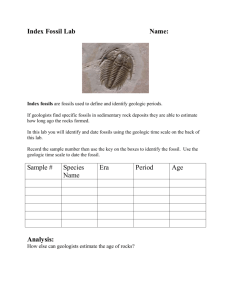

Chapter 5 The Fossil Record Preview Section 1 Geologic History Section 2 Looking at Fossils Section 3 Time Marches On Concept Mapping Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Bellringer “The Present is the Key to the Past.” This phrase was the cornerstone of the uniformitarianist theory developed by geologist James Hutton in the late 1700s. Write a few sentences in your science journal about how studying the present could reveal the story of Earth’s history. Use sketches to illustrate processes that occurred millions of years ago that you can still see today. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Objectives • Compare uniformitarianism with catastrophism. • Describe how the science of geology has changed over the past 200 years. • Contrast relative dating with absolute dating. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History The Principle of Uniformitarianism, continued • In Theory of the Earth (1788), James Hutton introduced the idea of uniformitarianism. • Uniformitarianism assumes that geologic processes that are shaping the Earth today have been at work throughout Earth’s history. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History The Principle of Uniformitarianism, continued • Uniformitarianism Versus Catastrophism During Hutton’s time, most scientists supported catastrophism, the principle that all geologic change occurs suddenly. • Supporters of catastrophism thought that Earth’s mountains, canyons, and seas formed during rare, sudden events called catastrophes. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History The Principle of Uniformitarianism, continued • Most people also believed that Earth was only a few thousand years old. • Hutton’s work suggested a very different reality. • According to his theories, Earth had to be much older, because gradual geologic processes would take much longer than a few thousand years. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History The Principle of Uniformitarianism, continued • A Victory for Uniformitarianism Catastrophism remained the guiding principle of geology in the early 19th century. • But uniformitarianism became geology’s guiding principle after Charles Lyell reintroduced the concept in his Principles of Geology (1830-1833). Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History The Principle of Uniformitarianism, continued • Using Hutton’s notes and evidence of his own, Lyell successfully challenged the principle of catastrophism. • He saw no reason to doubt that major geologic change happened at the same rate in the past as it happens in the present—gradually. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Modern Geology—A Happy Medium • During the late 20th century, scientists such as Stephen J. Gould challenged the principle of uniformitarianism. • They believed that catastrophes sometimes play an important role in shaping Earth’s history. • Neither theory completely accounts for all geologic change. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Modern Geology—A Happy Medium, continued • Most geologic change is gradual and uniform. • But catastrophes that cause geologic change have occurred during Earth’s long history. • Asteroid and comet strikes to Earth, for example, have caused rapid change. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Modern Geology—A Happy Medium, continued • Some scientists think an asteroid strike 65 million years ago caused the dinosaurs to become extinct. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Relative Dating • Scientists can use two methods to determine the age of objects in sedimentary rocks. • One of those methods is known as relative dating. • Relative dating examines a fossil’s position within rock layers to estimate its age. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Relative Dating, continued • The bottom layers of rock are usually the oldest, and the top layers are usually the youngest. • Scientists can use the order of these rock layers to determine the relative age of objects within the layers. • For example, fossils in the bottom layers are usually older than fossils in the top layers. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Relative Dating, continued • The Geologic Column To make relative dating easier, geologists combine data from all of the known rock sequences around the world. • From this information, geologists create the geologic column—an ideal sequence of rock layers that contains all of the known fossils and rock formations on Earth. • These layers are arranged from oldest to youngest. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Absolute Dating • Scientists can use absolute dating to more precisely determine the age of a fossil or rock. • In absolute dating, scientists examine atoms to measure the age of fossils or rocks in years. • Atoms are the particles that make up all matter. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Absolute Dating, continued • Some atoms are unstable, and will decay over time. • When an atom decays, it becomes a different and more stable kind of atom. • Each kind of unstable atom decays at its own rate. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Absolute Dating, continued • The time it takes for half of the unstable atoms in a sample to decay is known as the half-life of that atom. • Scientists can examine a sample of rock or fossil, and look at the ratio of unstable to stable atoms. • Since they know the half-life, they can determine the approximate age of the sample. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Absolute Dating, continued • Uranium-238 has a half-life of 4.5 billion years. Scientists can use uranium-238 to date rocks or fossils that are millions of years old. • Carbon-14 has a half-life of only 5,780 years. • Scientists use carbon-14 to date fossils and other objects that are less than 50,000 years old, such as human artifacts. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Radiometric Dating Click below to watch the Visual Concept. Visual Concept Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Paleontology—The Study of Past Life • Paleontology is the science involved with the study of past life. • Scientists who study past life are called paleontologists. • Paleontologists collect data by studying fossils, the remains of organisms preserved by geological processes. Chapter 5 Section 1 Geologic History Paleontology—The Study of Past Life, continued • Vertebrate and invertebrate paleontologists study the remains of animals. • Paleobotanists study fossils of plants. • Other paleontologists reconstruct past ecosystems, study the traces that animals left behind, and piece together the conditions under which fossils formed. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Bellringer Describe the fossil record of your own life that might be found 65 million years from now. What items, or artifacts, might be likely to survive? What kinds of things would decay and disappear? Do you think your fossil record would produce an accurate picture of your life? What might be missing? Write your description in your science journal. Later, you will share your description with the class. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Objectives • Describe five ways in which different types of fossils form. • List three types of fossils that are not part of organisms. • Explain how fossils can be used to determine the history of changes in environments and organisms. • Explain how index fossils can be used to date rock layers. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Fossilized Organisms • The remains or physical evidence of an organism preserved by geologic processes is called a fossil. • Fossils in rocks can form when an organism dies and is quickly covered by sediment. • When the sediment becomes rock, hard parts of the organism are preserved. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Fossilized Organisms, continued • If an insect is caught in sticky tree sap, the sap covers its entire body and hardens quickly. • Fossils in amber are entire organisms preserved inside hardened tree sap, called amber. • Some of the best insect fossils, as well as frogs and lizards, have been found in amber. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Fossilized Organisms, continued • Organisms can also be preserved by petrifaction. • Petrifaction is a process in which minerals replace the organism’s tissues. • Permineralization and replacement are forms of petrifaction. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Fossilized Organisms, continued • In the process of permineralization, pore space in an organism’s hard tissue (like bone or wood) is filled up with mineral. • In the process of replacement, minerals completely replace the tissues of the organism. • Some samples of petrified wood are composed completely of minerals. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Fossilized Organisms, continued • In some places, asphalt wells up and forms thick, sticky pools at Earth’s surface. • These asphalt pools can trap and preserve many organisms. • The La Brea asphalt deposits in Los Angeles, California have preserved organisms for at least 38,000 years. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Fossilized Organisms, continued • Frozen Fossils In 1999, scientists removed a 20,000-year-old woolly mammoth that was frozen in the Siberian tundra. • These mammoths became extinct about 10,000 years ago. • Because cold temperatures slow down decay, the mammoth was almost perfectly preserved. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Other Types of Fossils • Trace fossils are any naturally preserved evidence of animal activity. • Tracks are an example of a trace fossil. They form when animal footprints fill with sediment. • Tracks can reveal size and speed of an animal, and whether it traveled in groups. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Other Types of Fossils, continued • Burrows are another trace fossil. • Burrows are shelters made by animals that bury themselves in sediment, such as clams. • Another type of trace fossil is coprolite, or preserved animal dung. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Other Types of Fossils, continued • Molds and casts are two more examples of fossils. • A cavity in rock where a plant or animal was buried is called a mold. • A cast is an object that is created when sediment fills a mold and becomes rock. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Using Fossils to Interpret the Past • The Information in the Fossil Record The fossil record gives only a rough sketch of the history of life on Earth. • Most organisms never become fossils. • Many fossils have yet to be discovered. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Using Fossils to Interpret the Past, continued • Organisms with hard body parts have left more fossils than those with soft body parts. • Organisms that lived in areas that favored fossilization have also left more fossils. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Using Fossils to Interpret the Past, continued • But fossils can show a history of environmental change. • For example, the presence of marine fossils on mountaintops in Canada means that these mountains formed at the bottom of the ocean. • Marine fossils can also help scientists reconstruct ancient coastlines and detect the presence of ancient seas. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Using Fossils to Interpret the Past, continued • Scientists can use fossils of plants and land animals to reconstruct past climates. • By examining fossils, scientists can tell whether the climate of an area was cooler or wetter than that climate is now. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Using Fossils to Interpret the Past, continued • History of Changing Organisms Scientists study the relationships between fossils to interpret how life has changed over time. • Since the fossil record is incomplete, paleontologists look for similarities between fossils over time to try to track change. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Using Fossils to Date Rocks • Scientists have found that particular types of fossils appear only in certain layers of rock. • By dating rock layers above and below these fossils, scientists can determine the time span in which the organism lived. • If the organism lived for a relatively short period of time, its fossils would show up in limited layers. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Using Fossils to Date Rocks, continued • Index fossils are fossils of organisms that lived for a relatively short, well-defined geologic time span. • To be index fossils, these fossils must be found worldwide. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Using Fossils to Date Rocks, continued • Ammonites of the genus Tropites are index fossils. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Using Fossils to Date Rocks, continued • These ammonites were marine mollusks similar to modern squids. • Tropites lived between 230 million and 208 million years ago. • Fossils of these ammonites are index fossils for that time period. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Using Fossils to Date Rocks, continued • Trilobites of the genus Phacops are also index fossils. • Trilobites are extinct. Their closest living relative is the horseshoe crab. Chapter 5 Section 2 Looking at Fossils Using Fossils to Date Rocks, continued • Phacops lived about 400 million years ago. • When scientists find fossils of trilobites anywhere on Earth, they assume the rock layers are also approximately 400 million years old. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On Bellringer Archaeologists and paleontologists believe that modern humans have lived on Earth for 150,000 to 200,000 years. If we imagine the history of the Earth to be the length of one calendar year, on which date do you think modern humans arrived? Record your answer in your science journal. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On Objectives • Explain how geologic time is recorded in layers of sedimentary rock. • Explain how the geologic time scale illustrates the occurrence of processes on Earth. • Explain how the fossil record provides evidence of changes that have taken place in organisms over time. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On Geologic Time • Earth is about 4.6 billion years old. • Paleontologists find a record of Earth’s history in rock formations and fossils around the world. • Dinosaur National Monument in Utah contains the remains of thousands of dinosaurs that inhabited the area about 150 million years ago. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On Geologic Time, continued • Although 150 million years seems like an incredibly long period, it is little more than 3% of the time our planet has existed. • The Rock Record and Geologic Time One of the best places in North America to see Earth’s history recorded in rock layers is Grand Canyon National Park in northwestern Arizona. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On Geologic Time, continued • The Colorado River has cut the Grand Canyon nearly 2 km deep in some places. • Over the course of 6 million years, the river has eroded countless layers of rock. • These layers represent almost half, or nearly 2 billion years, of Earth’s history. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On Geologic Time, continued • The Fossil Record and Geologic Time Sedimentary rocks in the Green River formation can be found in parts of Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado. • These rocks are thousands of meters thick, and were once part of a system of ancient lakes that existed for millions of years. • Fossils of plants and animals are common in these rocks, and very well preserved. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale • The geologic column represents the billions of years that have passed since the first rocks formed on Earth. • Geologists study a total of 4.6 billion years of Earth’s history! • To make their job easier, geologists have created the geologic time scale, a scale that divides Earth’s history into distinct intervals of time. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • Geologists have divided Earth’s history into sections of time. • The largest divisions of time are eons. • The four eons are the Hadean eon, the Archean eon, the Proterozoic eon, and the Phanerozoic eon. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • The Phanerozoic eon is divided into three eras, which are the second-largest divisions of geologic time. • The three eras are further divided into periods, which are the third-largest divisions of geologic time. • Periods are divided into epochs, the fourth-largest divisions of geologic time. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On Earth-History Clock Click below to watch the Visual Concept. Visual Concept Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • The boundaries between geologic time intervals represent shorter intervals in which visible changes took place on Earth. • Some changes are marked by the disappearance of index fossil species. • Other changes can be recognized only by detailed paleontological studies. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • The Appearance and Disappearance of Species At certain times during Earth’s history, the number of species has increased or decreased dramatically. • A sudden increase in species is often a result of a relatively sudden increase or decrease in competition between species. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • Hallucigenia sparsa appeared during the Cambrian period, when the number of marine species greatly increased. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • The number of species can dramatically decline over a relatively short period of time as a result of a mass extinction event. • Extinction is the death of every member of a species. • Gradual events such as global climate change and changes in ocean currents can cause mass extinctions. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • The Paleozoic Era—Old Life The Paleozoic era lasted from about 543 million to 248 million years ago. • The Paleozoic era is the first era well represented by fossils. • Marine life flourished at the beginning of the Paleozoic era. However there were few land animals. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • By the middle of the Paleozoic era, all modern groups of land plants had appeared. • By the end of the era, amphibians and reptiles lived on the land, and insects were abundant. • The following slide shows what life might have looked like in the late Paleozoic era. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Late Paleozoic Era Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • The Paleozoic era came to an end with the largest mass extinction in Earth’s history. • Some scientists believe that ocean changes were a likely cause of this extinction. • The event killed nearly 90% of all species. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • The Mesozoic Era—The Age of Reptiles The Mesozoic era began about 248 million years ago. • The Mesozoic era is called the Age of Reptiles because reptiles such as dinosaurs dominated the land. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • Small mammals appeared about the same time that the dinosaurs did. • Birds appeared in the late Mesozoic era. • Many scientists think that birds developed directly from a type of dinosaur. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • At the end of the Mesozoic era, about 15% to 20% of all species on Earth became extinct. • This mass extinction event wiped out the dinosaurs. • Global climate change may have caused this extinction. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • The Cenozoic Era—The Age of Mammals The Cenozoic era began about 65 million years ago and continues to the present. • This era is known as the Age of Mammals. • During the Mesozoic era, mammals had to compete with dinosaurs and other animals for food and habitat. Chapter 5 Section 3 Time Marches On The Geologic Time Scale, continued • After the mass extinction at the end of the Mesozoic era, mammals flourished. • Unique traits may have helped these mammals survive the environmental changes that probably caused the extinction of the dinosaurs. • These traits include the ability to regulate internal body temperature and to develop young inside the mother. Chapter 5 The Fossil Record Concept Mapping Use the terms below to complete the concept map on the next slide. rock layers relative dating decay atoms fossils absolute dating Chapter 5 The Fossil Record Chapter 5 The Fossil Record