I. The PersianS AND THEIR Empire A. Building the Persian Empire

advertisement

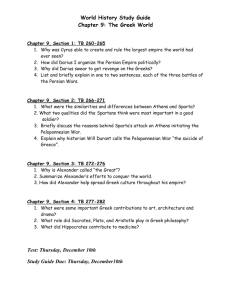

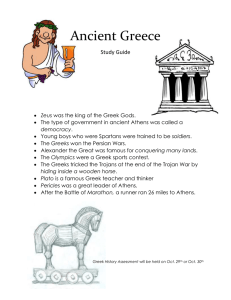

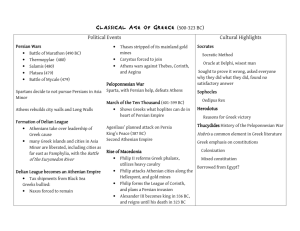

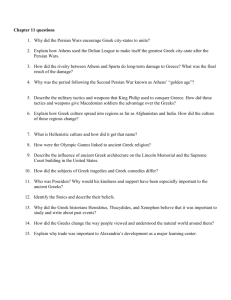

I. II. THE PERSIANS AND THEIR EMPIRE A. Building the Persian Empire 1. The Persian homeland was a plateau north of the Persian Gulf. 2. Trade routes connecting Mesopotamia and Anatolia to India and Central Asia passed through Persia. 3. Two societies competed for power in the early seventh century B.C.E., the Medes and the Persians. Ultimately, the Persians displaced the Medes. 4. The ruling family of Persia was the Achaemenids, whose four kings built the empire: Cyrus II “the Great” (r. 550–530 B.C.E.), and his successors Cambyses II (r. 530–522 B.C.E.), Darius I (r. 521–486 B.C.E.), and Xerxes I (r. 486–465 B.C.E.). 5. Under Cyrus, the Persian Empire conquered Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine, Lydia, and the Greek cities of Anatolia and parts of central Asia; Cambyses II conquered Egyptand Darius annexed Afghanistan and parts of northwestern India. 6. Darius completed the first Suez Canal, 125 miles long and 150 feet wide, and he began building a spectacular new capital at Persepolis. B. Imperial Policies and Networks 1. Persians used laws, generous economic policies, and tolerance in ruling the peoples they conquered. 2. Each of the Persian provinces was ruled by a satrap (“protector of the kingdom”) who ruled according to set laws and paid fixed taxes to the king. 3. Persians excelled at road building; their greatest was the 1,700-mile-long “royal road” from east to west that aided communication and could be traveled in nineteen days by a king’s messenger on horseback. 4. Persians allowed conquered peoples to maintain their local religions and social customs; furthermore, leading citizens came from all over the empire and used many official languages, including Aramaic and Greek. C. Persian Religion and Society 1. Monotheistic Zoroastrianism, founded by Zoroaster (“With Golden Camels”), celebrated the supreme good god Ahura Mazda who was locked in a contest with an evil spirit devil. 2. Other religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism, may have adapted Zoroastrianism’s ideas of ethical behavior and an afterlife in heaven or hell. 3. Persian society consisted of nobles educated by Zoroastrian priests, a middle class of artisans, and peasants and slaves at the bottom. 4. Persian society was generally patriarchal and polygamous, with wives of rich men secluded in harems. 5. Some women, such as Irdabama, became independently wealthy or controlled large estates. D. Warfare and Persian Decline 1. Darius unsuccessfully fought against the Scythians, whose territory stretched from Ukraine to Mongolia. 2. Inspired by the success of the Scythians, some Greek cities on the Ionian coast rebelled against Persia. 3. Darius attacked the cities on the Greek peninsula that were supporting the Ionian rebels but failed to conquer mainland Greece. He was able to stop the rebellions in the Ionian coastal cities. 4. Xerxes attacked the Greek city states in 480 B.C.E., but he was defeated. 5. Under Xerxes, higher taxes, inflation, high interest rates, and less inclusiveness towards minor groups led to rebellions that weakened the empire before Alexander the Great conquered it. THE RISE AND FLOWERING OF THE GREEKS A. The Greek City-States 1. B. C. D. E. D. The major institution of classical Greek life was the polis, or city-state, that gave citizens a sense of personal identity and meaning. 2. City-states competed fiercely in the Olympic Games, a religious festival where participants sought to win at all costs in wrestling, running, and other athletic events. 3. Only a small percentage (c. 20 percent) of the total population were citizens, and they were often further dominated by a tiny group of wealthy leaders or oligarchy. 4. By the seventh century, the growth of trade and the evolution of citizen-armies decreased the influence of aristocrats. Reform, Tyranny, and Democracy in Athens 1. A series of reforms begun by Solon about 594 B.C.E. to solve a debt crisis culminated in the redistribution of land under Peisistratus (561-527 B.C.E. and then the foundation of a democracy in 507 B.C.E. by Cleisthenes. 2. A Council of 500 submitted legislation to the Assembly, of 40,000 citizens. The Spartan System 1. The land-locked polis of Sparta on the Peloponnese peninsula developed a militaristic, aristocratic state. 2. Short of land, Spartans conquered their neighbors, creating a system of agricultural slaves who outnumbered Spartans, so the Spartans developed a rigid military state. 3. Spartans were led by two kings and a Council of Elders, twenty-eight men who were elected for life by an Assembly of citizens over thirty years of age. 4. Spartans practiced eugenics, abandoning physically unfit boys to die; other boys experienced military training. 5. Though they were not citizens, Spartan women had higher status, wealth, and independence than women in other Greek city-states. Religion, Rationalism, and Science 1. Gods and legends from the Homeric epics shaped Greek thinking and values, with elements from Egyptian and Phoenician beliefs. 2. Greek gods and goddesses represented natural and human activities: Zeus (leadership), his wife Hera (marriage and family), Poseidon (sea), Apollo (sun, music, and philosophy), Dionysus (wine), and Aphrodite (sex and love). 2. Humans maintained harmony with the immortal gods by performing sacrifices to appease their wrath; defying the gods led to disaster. 3. A rational tradition of philosophers included Thales, Anaximander, Democritus, Heracleitus, and Pythagoras. 4. The Sophists emphasized skepticism and relativism, arguing there is no ultimate truth. Axial Age Philosophy and Thinkers 1. Athenian philosophers Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle were part of the philosophical and religious revolution taking place across Eurasia 600-200 B.C.E., known as the Axial Age. 2. Socrates (469–399 B.C.E.) used his “Socratic Method” of questioning to challenge the relativism of the Sophists and led his interlocutors toward a belief in absolute truths. 3. Socrates chose to show his loyalty to Athens and to his ideals by accepting his fellow citizens’ death sentence for “corrupting the youth.” 4. Socrates’ student Plato (428–347 B.C.E.) founded the Academy in Athens and advocated that a special class of “Guardians” use reason to rule a just society. 5. Plato’s student Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.) studied human and physical nature, as well as the social and natural sciences and humanities; he pioneered the study of zoology. Literature 1. The wealth and culture of Athens made possible great dramatic and literary achievements. 2. The tragedies of Aeschylus (525–456 B.C.E.) examined issues of justice, those of Sophocles (ca. 497–406 B.C.E.) explored human and emotional issues, and the comedies of Aristophanes (448–380 B.C.E.) ridiculed Athenian leadership. 3. Vivid images of strong women appear, for example, in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. 4. Lyric poets were individualistic, such as Archilochus, who mocked the Spartan idea of heroism, and Sappho from Lesbos, who wrote love poems, inspired by Aphrodite. E. Greek Society 1. Greek society had pronounced differences between genders and social classes. 2. About one-third of the population were slaves, mostly captives from battle or debtors. 3. Greek families were limited to the nuclear family pattern of a husband, wife, and children. 4. Women suffered strong misogynist prejudice but could own property and divorce their husbands, and they often appeared as strong-willed characters in plays, such as Lysistrata by Aristophanes. 5. Greek society was very open about homosexuality. III. GREEKS, PERSIANS, AND THE REGIONAL SYSTEM A. The Greco-Persian Wars 1. Greek cities in Anatolia revolted against their Persian overlords in 499 B.C.E. and were defeated five years later. 2. The first Greco-Persian War ended with a Greek victory over the forces of the Perisan king Darius I at Marathon in 490 B.C.E. 3. Xerxes tried to conquer Greece but was defeated by the Athenian fleet at Salamis in 480 B.C.E. and by Greek infantry at Plataea in 479 B.C.E. 4. Athenians had developed the most advanced fighting ship, the trireme. B. Empire and Conflict in the Greek World 1. To defeat the Persians, Greek cities had organized a defensive alliance called the Delian League. 2. Athens dominated the Delian League, preferring to engage militarily against the island of Naxos rather than allow it to withdraw from this defensive alliance. 3. Athens enjoyed a golden age under Pericles (ca. 495-429 B.C.E.), a leader who promoted democratic legal reforms; during this era, Athenians built the Parthenon, a temple to Athena, on the hilltop Acropolis. 4. Athens’ arrogance and a series of misfortunes, including defeat at Syracuse on Sicily and a deadly plague in Athens, led to its defeat by Sparta during the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.E.). 5. Sparta became the most powerful Greek state, but conflicts between Greek cities led to decades of instability, and in less than a century, Greece was conquered by neighboring Macedonia. C. Historiography: Universal and Critical 1. Greek historians Herodotus and Thucycides developed critical, analytical concepts of history still in use today. 2. Herodotus (ca. 484-425 B.C.E.), sometimes called the Father of History, provided the main source of information about the Greco-Persian Wars. 3. Thucydides (ca. 460-400 B.C.E.) wrote The Peloponnesian War, including his critical judgments with his narrative and providing much of our knowledge about Greek politics and wars during the fifth century B.C.E. D. Interregional Trade and Cultural Mixing 1. The Mediterranean Basin was a huge trading zone; merchants became involved in a “trade diaspora,” living permanently in foreign cities. 2. Greek colonies throughout the Mediterranean spread Greek culture, grape cultivation, olive trees, and the use of metal coins. 3. The Greeks borrowed extensively from surrounding societies, such as the Phoenicians, Lydians, Egyptians, and Mesopotamians. E. The Persian and Greek Legacies 1. The Persian Empire left a legacy with traditions and ideas fused from multinational cultures, Zoroastrian ideas, and many words that have become part of the English language. 2. Many historians debate about how directly the Greeks influenced other cultures, demonstrating that Greece and Greek ideas remain fascinating subjects for study. IV. THE HELLENISTIC AGE AND ITS AFRO-EURASIAN LEGACIES A. Alexander the Great, World Empire, and Hellenism 1. Alexander “the Great” of Macedonia (r. 336–323 B.C.E.) created a huge empire, revitalized Greek society, and spread Hellenism, a combination of Persian and Greek cultures. 2. In thirteen years of brilliant but ruthless campaigning, Alexander conquered Egypt, dismantled the Persian Empire, and marched into India before his homesick troops refused to go further. 3. Alexander adopted the ruling traditions of the lands he conquered, encouraging his soldiers to marry Asian wives. 4. Hellenistic culture differed from that of classical Greece by placing more emphasis on the emotions, rather than individual freedom and reason. 5. When Alexander died of a fever in Babylon at age 33, his empire fragmented into areas ruled by his former generals: Ptolemy (Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean), Seleucus (Persia, Mesopotamia, and Syria), and Antigonus (Macedonia and Greece). B. Hellenistic Cities and Economic Networks 1. Alexander founded many cities named after him throughout his empire; Alexandria in Egypt retains this legacy today. 2. Hellenistic cities were not independent city-states but parts of kingdoms; city governments were run by aristocrats, professional soldiers, and bureaucrats. 3. The upper classes enjoyed an urban culture that glorified hedonism, lovemaking, drinking, and horse racing. 4. Hellenistic cities were cosmopolitan and ethnically diverse, and they linked the Mediterranean with western Asia in an enormous trading network. C. Science, Religion and Philosophy 1. Hellenistic thinkers continued the classical Greek interest in scientific, religious, and philosophical questions. 2. Hellenistic scientists and mathematicians included Euclid, who worked on plane geometry, Herophilus, who studied the brain, Aristarchus, who proposed a heliocentric approach to astronomy, Eratosthenes, who calculated the circumference of the earth within 200 miles, and Hero, who built a steam turbine. 3. Hellenistic philosophy and religion produced Cynicism, Stoicism, and Mithraism, all of which influenced the Romans and remained important in western Asia and the eastern Mediterranean for many centuries.