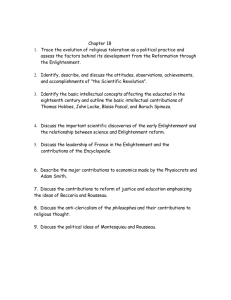

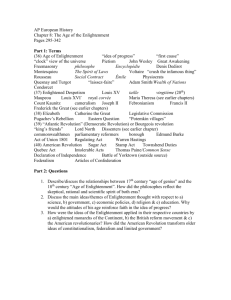

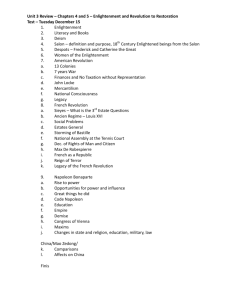

Ch. 10: Revolution and Enlightenment

advertisement

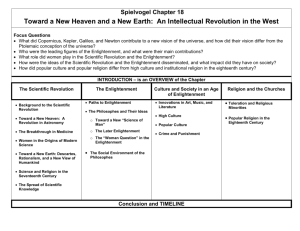

Ch. 10: Revolution and Enlightenment 1550 - 1800 I. The Scientific Revolution A. Background to the Revolution Science in the Middle Ages was practiced by natural philosophers, who studied the works of Aristotle and a few other Latin authors to understand the world around them. Experimentation was limited to the practice of alchemy. During the Renaissance, Europeans rediscovered texts in Greek by Ptolemy, Archimedes and Plato. These disagreed with Aristotle and broadened scientists’ perspectives. The printing press, new optical instruments like the telescope and microscope, and practical engineering problems all encouraged new types of thought. Classical texts on mathematics influenced the likes of Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo and Newton. They believed that all of nature could be understood through math. Their work set the stage for the Age of Reason. An alchemist’s lab Sir Isaac Newton I. The Scientific Revolution B. A Revolution in Astronomy Astronomy had always been an important field of study for European intellectuals. The movement and alignment of stars and planets was thought to have an affect on people’s destinies and the fates of nations. This belief is known as astrology, and it was taken very seriously by the elite. The European understanding of the universe was based on the knowledge and observations of Classical astronomers. In the Age of Enlightenment, those notions were challenged by new measurements and mathematical proofs. I. The Scientific Revolution C. The Ptolemaic System Ptolemy Ptolemy (AD 90-168) was the greatest astronomer of the Classical age. His ideas and written works were well known to natural philosophers of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. His calculations, in connection with the ideas of Aristotle and the worldview of early Christianity, produced the Ptolemaic, or geocentric, system. In the Ptolemaic system, the Earth is believed to be stationary at the center of the universe. Around the Earth are ten clear crystal spheres, which rotate independently of one another. The sun, moon, planets and stars are attached to these spheres. The outermost heavenly sphere was known as the “prime mover,” which moved on its own and gave motion to the inner spheres. Beyond the prime mover was heaven. In Ptolemy’s view, as adapted by Christian scholars, the Earth was the center and most important part of the universe. Even so, Man’s goal was to make his way to God beyond the universe. I. The Scientific Revolution Preview Copernicus and Kepler Galileo Newton Pgs. 295 - 297 Nicholas Copernicus Johannes Kepler Galileo Galilei Sir Isaac Newton I. The Scientific Revolution D. Copernicus and Kepler The Polish-born mathematician Nicholas Copernicus (1473 – 1543) believed that the geocentric system was unnecessarily complicated. In his book, On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, he suggested that the motions of the planets and stars make more sense when viewed as a sun-centered, or heliocentric, system. The Copernican heliocentric system held that the moon rotates around the Earth, the Earth rotates around the sun, and the Earth revolves on its axis every 24 hours. This explains why the sun appears to move from the Earth’s perspective. The heliocentric theory was further supported by the observations of Johannes Kepler (1571 – 1630), a German mathematician. Kepler’s analysis of thousands of measurements showed that the planets did not follow circular orbits, but elliptical ones. This is known as Kepler’s First Law, and it explained all apparent inconsistencies in Copernicus’s model. Heliocentric model Kepler’s First Law I. The Scientific Revolution E. Galileo The heliocentric model gained acceptance amongst scientists, but it posed further questions. An Italian astronomer named Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642) attempted to answer some of these questions through observation. He was the first European scientist to look at the planets through a telescope. Galileo’s observations of mountains on the moon and sunspots demonstrated that other celestial bodies were made of matter, just like the Earth. This refuted to Ptolemaic idea that the planets and stars were orbs of pure light. Galileo’s ideas were much more widely read than those of Copernicus and Kepler, largely because his book, The Starry Messenger, was written for a general audience. Unfortunately for Galileo, this got the attention of the Catholic Church. Copernican astronomy seemed to challenge the Christian concept of the universe and Man’s place in it. The Church, fearful of Galileo’s ideas and influence, forced him to recant. He spent the last ten years of his life under house arrest. I. The Scientific Revolution F. Newton Isaac Newton (1642 – 1727) was a latter-day Renaissance man. He was a professor of mathematics at Cambridge University, he developed and made his own optical instruments, he studied medicine and anatomy, and he was an acknowledged expert on the biblical Apocalypse. Newton’s most important work, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (called the Principia), defines the laws of motion governing all objects. The universal law of gravitation states that all objects in the universe exert an attraction on one another, which is why the planets orbit around the more massive sun. All of Newton’s work is based on precise measurements and provable mathematical formulas. Newton’s theorems demonstrated that the all motion in the universe could be explained by mathematical principles. This was the foundation for a new, mechanistic view of the world which would persist until the early twentieth century. I. The Scientific Revolution Preview Breakthroughs in Medicine & Chemistry Women & the Origins of Modern Science Descartes and Reason Pgs. 297 - 298 I. The Scientific Revolution G. Breakthroughs in Medicine & Chemistry Until the Renaissance, medicine had been based on the works of Galen, a Classical-era Greek physician. Galen’s understanding of anatomy and disease came from animal dissections. Andreas Vesalius (1514 – 1564), a professor at the University of Padua, dissected human remains and wrote the book, On the Fabric of the Human Body. He corrected many of Galen’s errors through careful examination. The circulatory system was described by William Harvey (1578 – 1657) in his work, On the Motion of the Heart and Blood. He showed that the same blood circulates throughout the body, and that the heart is the source of its motion. The science of chemistry was pioneered by Robert Boyle (1627 – 1691), who conducted the first laboratory experiments. Boyle’s Law states that the volume of a gas is dependent on the pressure exerted on it. Antoine Lavoisier (1743 – 1794) was the first chemist to try and organize the known elements by their properties. His efforts led to the Periodic Table. I. The Scientific Revolution H. Women & the Origins of Modern Science Prominent women were also engaged in scientific endeavors in the seventeenth century. Margaret Cavendish (1623 – 1673), an Englishwoman of noble birth, criticized the popular belief that science could make humanity the masters of nature. In one of her books, Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy, she stated: “We have no power at all over natural causes and effects… for man is but a small part, his powers are but particular actions of Nature, and he cannot have a supreme and absolute power.” In Germany, up to 14% of astronomers were women who had been trained at observatories by their husbands or fathers. One such woman, Maria Winkelmann (1670 – 1720), discovered comets and made original contributions to astronomy. When she applied for a position at the Berlin Academy, she was denied because she was a woman with no university degree. Margaret Cavendish Maria Winkelmann I. The Scientific Revolution I. Descartes and Reason “The Thinker” by Rodin The new philosophy of European scientists of the seventeenth century is best exemplified by the French thinker Rene Descartes (1596 – 1650). Descartes’ approach to understanding the universe was the axiom, “I think, therefore I am.” By this he meant that in order to study anything else, he must first recognize that he himself was real. All other information was to be approached through doubt. He reasoned that the material world and everything in it could be doubted, so they must be very different from the mind, which could not be doubted. Descartes’ notion that mind and matter were separate led scientists to deal with the material world as a subject of study independent from philosophy. The application of reason to the study of matter is called rationalism, and Descartes is credited with its invention. I. The Scientific Revolution II. The Enlightenment Preview The Scientific Method Path to the Enlightenment Philosophes and their Ideas Pgs. 299 - 302 I. The Scientific Revolution Homework Answer each question in a half-page response with complete sentences. Be accurate, be specific, be complete. Due tomorrow. 1. Name the four great mathematicians who had a profound impact on astronomy. For each one, briefly summarize what he contributed. 2. How did Vesalius and Harvey disprove many of Galen’s theories? 3. What is the significance of Descartes’ principle of the separation of mind and matter? I. The Scientific Revolution J. The Scientific Method Scientists wanted to understand the physical world in a systematic manner. They wanted a way to organize information and guarantee that their findings were reliable. The resulting system is called the scientific method. The scientific method was developed by Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626), who was not really a scientist. Bacon suggested that, rather than rely on ancient authorities like Aristotle, scientists should employ inductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning involves moving from the particular to the general, or from observed phenomena through experimentation toward general principles. Bacon was not interested in pure science. He viewed scientific endeavor as a means to provide humanity with new technologies and capabilities. His ultimate goal was to “conquer nature in action.” Sir Francis Bacon II. The Enlightenment A. Path to the Enlightenment The Scientific Revolution had a tremendous impact on the philosophers of the eighteenth century. The belief in reason as humanity’s greatest tool for progress was important to the Enlightenment movement. Enlightenment thinkers wrote a great deal about reason, as well as natural law, hope and progress. Isaac Newton (1643 – 1727) was a major influence on the Enlightenment. His mechanistic universe led philosophers to believe that if they could discover the principles on which nature operated, then they could apply them to how society operated. John Locke (1632 – 1704) also influenced the Enlightenment when, in his Essay Concerning Human Understanding, he suggested that the mind was created by its experience and observation. This encouraged philosophers to believe that the environment could be changed so as to produce the perfect mind and therefore the perfect society. John Locke II. The Enlightenment B. Philosophes and Their Ideas The important thinkers of the Enlightenment were of the middle and upper classes. They were authors, teachers, economists and social reformers. While they were not philosophers in the strictest sense, they were known by the French term “philosophes.” The early influences of the Enlightenment were largely English, including Newton and Locke, but those who spread the movement were mostly French. They synthesized the ideas of the earlier generation into a social program and spread it to other parts of Europe. The goal of the philosophe was to improve society through the application of reason and rational criticism. Over the course of a century, this agenda was pursued in different ways by different philosophes. They often disagreed with one another, and their ideas became more radical later in their era. II. The Enlightenment Preview Montesquieu Voltaire Diderot Pgs. 302 - 303 II. The Enlightenment C. Montesquieu Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (1689 – 1755) studied the law. In his The Spirit of the Laws, he attempted to use the scientific method to determine which laws were natural, or universal. Montesquieu’s investigation led him to identify three types of governments: Republics, which work well for small groups of citizens Despotism, which is ideal for large nations Monarchies, which work best for mid-sized states, like England Montesquieu identified the three branches of England’s government: Executive, Legislative and Judicial. These three branches maintain a separation of powers through the use of checks and balances. Montesquieu’s analysis, when translated into English, became a principle founding document for the American Constitution. II. The Enlightenment D. Voltaire Perhaps the most influential, and certainly the most prolific, thinker of the Enlightenment was FrancoisMarie Arouet (1694 – 1778), known as Voltaire. He wrote hundreds of letters, essays, histories, plays and novels, including Candide. Voltaire was an advocate of deism, a religious philosophy that was popular among eighteenth century intellectuals. Deists believe that the universe was created by a great mechanic, usually associated with God, who designed the laws of physics and matter. The universe operated along these guidelines in a mechanistic way without further involvement from God. Voltaire was also a champion of religious toleration. He criticized religious persecution in France in his book, Treatise on Toleration in 1763. He was also known to be a critic of Christianity in general. Voltaire The deist universe II. The Enlightenment E. Diderot Denis Diderot (1713 – 1784) attended the University of Paris. His original intent was to become a lawyer or enter the Church. Instead, he pursued a career as a freelance writer, much to his father’s disappointment. Writing allowed Diderot to study any subjects that appealed to him and learn whatever he could. Diderot was passionate about knowledge for its own sake. Denis Diderot His life’s work was the Encyclopedia, or Classified Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Trades, published between 1751 and 1772. The Encyclopedia had 28 volumes and included all the information Diderot and other contributors could collect. Alchemy lab Unlike a modern encyclopedia, Diderot’s work included articles that argued for a reform of the ancien regime. They attacked superstitions and supported religious toleration, they called for changes to the law and political practices. The Encyclopedia was especially popular amongst middleCobbler’s tools class intellectuals like doctors, lawyers and the lower clergy. II. The Enlightenment Preview Toward a New Social Science Economics Beccaria and Justice Pgs. 303 - 304 II. The Enlightenment F. Toward a New Social Science Newton’s idea of a mechanistic universe had led the philosophes to believe that all aspects of the world could be understood through underlying natural laws. Intellectuals believed that human institutions were also subject to natural laws, and that these laws could be understood through scientific exploration. Once the laws were understood, they could be exploited to improve society for the betterment of all people. The search for these universal laws led to the development of the social sciences, a set of academic disciplines that include economics and political science. II. The Enlightenment G. Economics The first attempt to establish the universal laws of economics was made by a group of French philosophes called the Physiocrats. Led by Francois Quesnay (1694 – 1774) and Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot (1727 – 1781), they reasoned that if everyone were free to follow their own self-interest, then all of society would benefit. This idea, called laissez-faire (from the French phrase meaning “to let people do what they want”) economics, became popular in the late eighteenth century. Laissezfaire economics held that the government should not interfere via taxes or regulations. The ideas of the Physiocrats were taken to a new level with the works of the Scottish economist Adam Smith (1723 – 1790). In his Wealth of Nations, Smith argued that the government’s only role was to provide for an army, a police force, and expensive public works like roads and canals. Francois Quesnay Adam Smith II. The Enlightenment H. Beccaria and Justice Flaying Cesare Beccaria In the 1700s, nearly every European nation had a judicial system and a set of courts. The punishments handed down by these courts were often brutal, involving maiming and public execution. The reason for these harsh penalties was to deter future criminals, as the police were not adequately equipped to investigate crimes. The philosophe Cesare Beccaria (1738 – 1794) disagreed with the idea of capital punishment. In his 1764 book, On Crimes and Punishments, he argued that public executions did not prevent future crimes. Instead, displays of brutality simply made people more comfortable with brutality. Beccaria’s essays on criminal justice represented a more practical and less theoretical approach than other leading authors, including Samuel von Pufendorf. He advocated the use of imprisonment for reform rather than punishment. II. The Enlightenment Preview The Later Enlightenment Rights of Women Pgs. 304 - 305 II. The Enlightenment Homework Answer each question in a half-page response with complete sentences. Be accurate, be specific, be complete. Due tomorrow. 1. What are the characteristics of the scientific method? 2. What contributions did Isaac Newton and John Locke make to Enlightenment thought? 3. What were the major contributions of Montesquieu, Voltaire, and Diderot to the Enlightenment? II. The Enlightenment I. The Later Enlightenment The latter stage of the Enlightenment began in the 1760s, with the work of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1717 – 1778). Rousseau spent the early years of his life working at various jobs in France and Italy. He was eventually brought into the company of the philosophes in Paris. In Discourse on the Origins of the Inequalities of Man, Rousseau argued that people invent laws and government to protect their property, and that governments take away people’s rights in exchange for safety. In The Social Contract, Rousseau suggests that a society agrees to abide by a set of rules, called a social contract. Those individuals who prefer to follow their own selfinterest may be forced to follow the social contract, which benefits the “general will” and creates liberty for the entire community. Jean-Jacques Rousseau The Social Contract II. The Enlightenment I. The Later Enlightenment Frontispiece to Emile Death mask In Emile, a novel, Rousseau makes the point that education should encourage children’s natural inclinations, no restrict them. This is in line with Rousseau’s belief that emotions, as well as reason, are necessary for the development of the human mind. Other philosophes had de-emphasized the role of emotions in favor of pure reason. Rousseau’s personal attitudes paint him as something of a hypocrite. He sent his own children off to be raised in orphanages. He believed that women were fundamentally different than men, less accustomed to thought or work. In Rousseau’s personal view, women should be educated only in obedience and nurturing, so that they could be supportive wives and mothers. Nothing more was required of them. II. The Enlightenment J. Rights of Women With few exceptions, European intellectuals had minimized the role of women for centuries. Women were regarded as inferior in intelligence and energy. This attitude made male domination of women possible, and justified it after the fact. By the early eighteenth century, female intellectuals were challenging this paradigm. Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 – 1797) is known as the founder of the modern women’s rights movement. In her book, A Vindication of the Rights of Women, she identified two flaws in Enlightenment thinking: On the one hand, philosophes had said that arbitrary political power was wrong. On the other hand, they said that women had to obey men. Wollstonecraft asserted that this was equally wrong. The Enlightenment had been based on the supremacy of reason. Since women had reason to the same degree as men, then women should have equal rights and opportunities. Mary Wollstonecraft Suffragettes II. The Enlightenment Preview Social World of the Enlightenment The Growth of Reading The Salon Religion in the Enlightenment Pgs. 305 - 307 II. The Enlightenment K. Social World of the Enlightenment Fancy folks Vive la Revolicion! The Enlightenment was not entirely an aristocratic movement. Philosophes came from various social and economic backgrounds. Rousseau and Diderot, among others, were from lower-middle-class families. While not all of the celebrated thinkers were from the aristocracy, the Enlightenment appealed most to the wealthier classes. The lower nobility and wealthy urban professionals made up the majority of the movement’s audience. The urban poor and the peasantry had relatively little interest in the intellectual pursuits of the upper classes. Neither did they have much to gain from their ideas, at least not until the end of the eighteenth century. II. The Enlightenment L. The Growth of Reading The publishing industry expanded dramatically during the 1700s. In France, the number of books published annually rose from 300 to 1,600 over 30 years. This was related to a profound change in reading habits. Books had been written and published with small, specialized markets in mind. By the end of the eighteenth century, the lower-middle class were reading for pleasure and education. Women bought books at a much greater rate. This is how Enlightenment ideas spread throughout society. The spread of available print media was not limited to books. Magazines became increasingly popular through the course of the 1700s. By 1780, 158 different magazines were published in London alone. Daily newspapers appeared for the first time in 1701. They were cheap enough to appeal to the urban poor, and were often provided for free in coffeehouses. II. The Enlightenment M. The Salon Among the aristocracy and urban wealthy classes, it became a common practice to hold gatherings of intellectuals in private houses. Artists, scientists, writers and other philosophes would gather in a large sitting room in the home of a wealthy patron and discuss the new ideas of the time. This practice came to be named after the room it occurred in: the salon. The most fashionable salons began to attract the attention of politicians and aristocrats. The Paris home of Madame Marie-Therese de Geoffrin (1699 – 1777) became so well-known for its intellectual discussions that future kings of Sweden and Poland begged to be invited. This glamour helped popularize Enlightenment ideas. Mme. Geoffrin II. The Enlightenment N. Religion in the Enlightenment John Wesley Methodism While prominent philosophes became deists or atheists, this did not reflect the religious sentiment of Europe at the time. The majority of people were Christians, and many became more spiritual in this era. The spiritual fervor of the early Protestant Reformation had dissipated by the eighteenth century. It was replaced by statecontrolled churches that often lacked enthusiasm. This led to parishioners seeking spiritual depth in new movements. The most influential of these new movements was Methodism, founded by John Wesley (1703 – 1791) in England. Wesley received a mystical revelation and spent the rest of his life preaching his “glad tidings” of salvation to the poor. Methodist societies focused on good works and cooperation. Methodism stresses hard work and spiritual contentment, which are said to be more valuable than social or political equality. The Methodist Church therefore proved that spiritual satisfaction was still important in a world that emphasized reason. III. The Impact of the Enlightenment Preview The Arts Architecture and Art Music Literature Pgs. 308 - 310 III. The Impact of the Enlightenment A. The Arts The impact of the Enlightenment was not limited to philosophy and science. Ideas changed how artists approached their work as well. While traditional forms persisted in some fields, such as portraiture, the eighteenth century saw the development of new techniques in painting, architecture, music and literature. III. The Impact of the Enlightenment B. Architecture and Art Church of the 14 Saints Ceiling of the Residence The monarchs of Europe built immense residences. These palaces exhibited Renaissance styles as much as Baroque. The combination created a new style: neoclassical. The neoclassical style features religious and secular themes, bright colors, and extreme ornamentation. The Church of the Fourteen Saints and the Residence of Wurzburg, both by Balthasar Neumann (1689 – 1783), are prime examples of the style. By the 1730s, a new style had replaced neoclassical. Called rococo, this trend featured graceful curves and soft colors to suggest a happy, bright mood. Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684 – 1721) painted aristocrats enjoying pastoral entertainment. There is a sadness, suggesting the short-lived nature of pleasure. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696 – 1770) painted scenes full of enchantment and enthusiasm, like the ceiling of the Residence at Wurzburg. III. The Impact of the Enlightenment C. Music Some of the most profound music in history was composed in the eighteenth century. The four principle geniuses of the century are associated with the Baroque (Bach and Handel) and classical (Haydn and Mozart) music: Johann Sebastian Bach: Bach spent his entire life in Germany. He was a notable organist and composer, most famous for his Mass in B Minor. George Frederick Handel: Handel spent much of his career writing for the court of King George I of England. His Messiah appeals to nearly everyone, yet is a subtle masterpiece. Franz Joseph Haydn: Haydn began his career writing court music in Hungary, but later composed popular pieces in England, including The Creation and The Seasons. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Mozart began his musical career at the age of four. He was never a financial success, but his operas (The Marriage of Figaro, The Magic Flute, Don Giovanni) are among the greatest in history. III. The Impact of the Enlightenment D. Literature The novel continued to develop as a unique form of literature. As literacy spread to more social classes in the eighteenth century, the practice of reading for pleasure became common amongst the middle class. The novel also became an opportunity for authors to make criticisms of the age they lived in. Characters came to represent the various classes and were used to ridicule the social order. Henry Fielding (1707 – 1754), an English novelist, wrote about immoral characters who succeed through trickery and intellect. His most famous novel, The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, is a comedy in which the protagonist makes a fool of the aristocracy and takes advantage of the London poor. III. The Impact of the Enlightenment Preview Enlightenment and Enlightened Absolutism Prussia: Army and Bureaucracy The Austrian Empire Russia under Catherine the Great Enlightened Absolutism? Pgs. 310 - 312 II. The Enlightenment Homework Answer each question in a half-page response with complete sentences. Be accurate, be specific, be complete. Due tomorrow. 1. What is the concept of laissez-faire? Who came up with it? How did Adam Smith add to the idea? 2. What were Rousseau’s basic themes as presented in The Social Contract and Emile? 3. What are the central ideas of Methodism? III. The Impact of the Enlightenment E. Enlightenment & Enlightened Absolutism Eighteenth century philosophes intended to reform society in a rational way. They believed in natural rights, and they believed that the state should protect these rights. Therefore, a truly enlightened government should guarantee the following: equality before the law; freedom of religious worship; a free press; the right of assembly; property ownership; and the pursuit of happiness. Most philosophes believed that society should be governed by enlightened monarchs, who protected natural rights and fostered the arts and sciences. They should obey the laws and enforce them fairly. For a long time, historians described the monarchies of eighteenth century Europe as examples of enlightened absolutism. By this, they meant that the rulers maintained their royal authority while attempting to support Enlightened philosophies. Phillip III of Spain III. The Impact of the Enlightenment F. Prussia: Army and Bureaucracy Prussia became a major power in Europe under the leadership of two eighteenth century kings, Frederick William I (1688 – 1740) and Frederick II the Great (1712 – 1786). They developed the Prussian state along two traditional lines: The bureaucracy and the army. The Prussian bureaucracy was based on absolute loyalty to the monarch, and it stressed obedience and honor among its thousands of governmental workers. By 1740, Prussia’s army was the fourth largest in Europe, even though the nation had only the thirteenth largest population. Officers came from among the Junkers, and also held a strong sense of loyalty to the monarch. Frederick the Great was fond of Enlightenment ideas. He was acquainted with philosophes and he made progressive changes to the state, like abolishing torture, religious persecution, and censorship. However, he maintained serfdom and the medieval social structure. III. The Impact of the Enlightenment G. The Austrian Empire By the early 1700s, the Austrian Empire had become one of the most influential nations in Europe. Management of the empire was still a challenge, as it was composed of more than a dozen semi-autonomous states. Empress Maria Theresa (1717 – 1780) attempted to centralize authority and alleviate the conditions of the serfs, though she did not pursue Enlightened reforms. Maria Theresa’s son, Emperor Joseph II (1741 – 1790), was a true Enlightened monarch. He abolished serfdom and the death penalty, established religious toleration and equality under the law. Unfortunately, Joseph’s reforms were wholly unpopular. He was opposed by the aristocracy for freeing the serfs, the Catholic Church for imposing religious toleration, and the serfs for their loss of livelihood. The subsequent Austrian emperors had to undo all of Joseph’s work. Joseph II III. The Impact of the Enlightenment H. Russia under Catherine the Great Catherine the Great Peter the Great’s death in 1725, there was a series of six weak czars who were all assassinated or removed by their guards. The last of these, Peter III (1728 – 1762), was succeeded by his German wife. She ruled Russia as Catherine II the Great (1729 – 1796). Catherine was an intelligent and dynamic woman. She knew some of the philosophes and conversed with Diderot about his ideas for reforming Russian law. She did not implement them because she felt they would not work for the Russian people, especially the nobility. Catherine’s policies favored the aristocracy, which made conditions worse for the peasants. A rebellion broke out in 1774, led by a Cossack named Emelyan Pugachev. The rebellion was defeated, and Catherine instituted even harsher conditions for the serfs. Under Catherine’s rule, Russia expanded to the Black Sea in the southwest and annexed roughly half of Poland. III. The Impact of the Enlightenment I. Enlightened Absolutism? Of the three eastern European monarchs discussed, two of them (Frederick, Catherine) were more interested in maintaining the status quo than with meaningful Enlightened reform. They knew the philosophes and appreciated their ideas, but made little effort to implement them. In fact, all three rulers were more concerned with maintaining power and increasing tax revenue than with Enlightened rule. While the philosophes argued that warfare was wasteful and ultimately self-destructive, the monarchs of Europe still competed with one another to build the biggest armies and wage costly wars against one another. Kings and emperors became obsessed with the notion of a balance of power, where each nation would be prevented from becoming too powerful by the combined efforts of its neighbors. This balance often led to wars of conquest and precarious alliances. III. The Impact of the Enlightenment Preview War of the Austrian Succession The Seven Years’ War New Allies The War in Europe Pgs. 313 - 315 III. The Impact of the Enlightenment J. War of the Austrian Succession The balance of power in Europe led to a global war in 1740. The War of the Austrian Succession (1740 – 1748) was triggered when the emperor of Austria died and the throne passed to his daughter, Maria Theresa. Frederick the Great of Prussia saw a woman on the throne as a sign of weakness and invaded the Austrian territory of Silesia. The system of alliances that guaranteed the balance of power meant that France declared war on Austria, while Great Britain declared war of France and Prussia. Fighting took place on three continents: Prussia attacked in Silesia and France invaded the Netherlands; France captured Madras from the British in India; and Britain besieged the French fortress at Louisbourg in Canada. In 1748, all parties were exhausted by fighting. They signed the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which returned all captured territories to their original owners. Prussia refused to return Silesia to Austria, which set off another global war. Siege of Louisbourg Surrender of Madras III. The Impact of the Enlightenment K. The Seven Years’ War Empress Maria Theresa Hungarian grenadiers The loss of Silesia was something that Maria Theresa could not accept. From the moment that Prussia refused to return the territory, the empress began planning a further war. The Austrian army had been badly beaten during the War of the Austrian Succession and needed to be rebuilt. Maria Theresa spent eight years reorganizing her forces. Even with a new army, the empress knew that she could not beat the combined forces of Prussia and France. She set about turning the French against their recent allies. Her success in this field has been called a “diplomatic revolution.” III. The Impact of the Enlightenment L. New Allies Maria Theresa’s diplomatic coup was to get France to change sides. France and Austria had been bitter enemies for 200 years, and yet the French disliked the British even more, and they hoped to gain colonial territories from Britain. Therefore, France joined an alliance with Austria against Prussia. This new alignment of nations led to other unlikely pairings. Britain also wished to seize colonial territory, so they allied themselves with Prussia against Austria and France. Russia, a new participant on the European stage, was worried that Prussia posed a threat to their frontiers, and so joined in with Austria and France. The final alignment of nations: Austria, France and Russia versus Prussia and Britain. In 1756, war broke out again. It involved fighting in Europe, India and North America. It was known as the Seven Years’ War (1756 – 1763), and as the French and Indian War in America. King George III of Great Britain III. The Impact of the Enlightenment M. The War in Europe Frederick the Great Peter the Not-So-Great All five of the major powers participated in the European theater of the war. Fighting took place in Prussia, Austria, Germany and the Netherlands. For most of the war, Frederick the Great’s remarkable generalship allowed the Prussian army to defeat the forces of Austria, France, and Russia all at the same time. Eventually, the overwhelming numbers of his enemies were too great, and Frederick was forced to retreat. In 1762, Frederick’s luck changed. The czarina of Russia, Elizabeth, died and was replaced on the throne by her nephew, Peter III. Peter was German by birth and culture, and he immediately withdrew the Russian army from the war. This gave Frederick the opportunity to hold off the Austrians and French and force a stalemate. The European war ended in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris. Invaded territories were returned, and Austria recognized Prussia’s ownership of Silesia. III. The Impact of the Enlightenment Preview The War in India The War in North America Pgs. 315 - 316 III. The Impact of the Enlightenment N. The War in India Both Britain and France were involved in the Seven Years’ War in order to acquire colonies from one another. The colonial theaters of the war saw much more immediate gain for these two powers. At the end of the War of the Austrian Succession, France had been forced to return Madras to the British. This same conflict was renewed in 1756, with the French attempting to seize British towns and forts in India. Over the course of the war, Britain was victorious. This was not due to the size or superiority of the British army, which was in fact quite small and inept. Instead, it was the persistence of British forces. They simply outlasted the French. In the Treaty of Paris, France gave up all claim to India and left the subcontinent in uncontested British control. India would be part of the British Empire for 200 years. A maharaja surrenders to the British III. The Impact of the Enlightenment O. The War in North America Fort Carillon The battles in North America were more decisive and on a larger scale. Here, the war was known as the French and Indian War. French colonies in the New World were organized differently from their British counterparts. Canada and Louisiana were vast wildernesses that the French government ran as game preserves and trade markets. There were very few French colonists in North America, and most of them traded in furs, leather, timber and fish. By contrast, British North America was densely populated. The thirteen Atlantic colonies were home to over a million British subjects, and featured heavy industry and agriculture. There were two theaters to the American campaign. One centered on the French fortress at Louisbourg on the Gulf of St. Lawrence. This one fort commanded the river approaches to French Quebec, the most prosperous and populated part of Canada. III. The Impact of the Enlightenment O. The War in North America The second theater of the war was in the Ohio River Valley. The French occupied the valley so they could deny the British access to its rich farmlands. The French contracted Native American tribes as allies. They preferred the French, who were only interested in trade, to the British, who settled and took over land. In the early stages of the war, the larger French army was victorious. The prime minister of Britain, William Pitt the Elder, decided to make America his primary focus, diverting forces from Europe to help. He used the superiority of the British navy to cut the French off from supplies and reinforcements. In 1759, the British General Wolfe defeated the French General Montcalm outside Quebec City on the Plains of Abraham. From there, the British drove the French out of Canada, the Great Lakes and Ohio. In the Treaty of Paris, Britain received Canada and everything east of the Mississippi, including Florida from Spain. Spain was given Louisiana in exchange. Pitt the Elder Wolfe’s army at Quebec IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution Preview Colonial Empires in Latin America Economic Foundations State and Church Pgs. 318 - 320 III. The Impact of the Enlightenment Homework Answer each question in a half-page response with complete sentences. Be accurate, be specific, be complete. Due tomorrow. 1. What are the characteristics of the rococo style? Who were its most famous artists? 2. What effect did enlightened reforms have in Prussia, Austria, and Russia? 3. What was the War of the Austrian Succession about? What countries fought and on which side? IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution A. Colonial Empires in Latin America Spain and Portugal had colonized the New World beginning in the early sixteenth century. Spain came to own parts of North America, virtually all of Central America, and most of South America. Portugal had received Brazil as part of the Treaty of Tordesillas. Latin American culture, which includes all of the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking regions of the New World, is the product of a unique mix of influences. The Spanish authorities permitted, and even encouraged, intermarriage between European colonists and Native Americans. The product of these unions were called mestizos, and they occupied a social class of their own. In addition, the Spanish and Portuguese colonies imported millions of Africans to work the plantations. Unions between Europeans and Africans, while not condoned by the authorities, did happen, and the offspring were known as mulattoes. This group occupied a precarious position in Latin American society, similar to that of African slaves. IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution B. Economic Foundations Spanish and Portuguese colonies in the New World were operated for profit. Initially, profit came in the form of gold and silver, which were mined and sent back to Europe. After about 1650, the mines became less productive, and agriculture became a more profitable enterprise. Agriculture in Latin America was organized along the plantation system. Wealthy planters owned huge farms, which they operated with slave labor or Native American tenant farmers. Native peasants might also own small subsistence farms on poor land. This pattern of land ownership is still practiced today. The mercantilist trade system operated in Latin America as well. The colonies shipped sugar, tobacco, diamonds and furs to Europe in exchange for manufactured goods. Like other mercantilist powers, Spain and Portugal tried to keep competition out of their colonies. By the 1700s, however, France and Britain were too powerful to be restrained. Mexican laborers, by Edwards Modern sugarcane workers IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution C. State and Church Cathedral, Mexico City Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz The great distance between Europe and Latin America made it very difficult for Spanish or Portuguese monarchs to control their colonies. In many cases, and for hundreds of years, local administrators were allowed to govern any way they pleased. The Catholic Church played a major role in the administration of Latin America. The Dominican, Franciscan and Jesuit orders established missions all over the Spanish colonies in order to convert the native population. These missions made the natives more docile and easier to preach to. The Catholic Church also built cathedrals, hospitals and schools for the population of Latin America. They provided basic education and some economic opportunities. The Church established convents, where women could become nuns as an alternative to marriage. One such nun, Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz (1651 – 1695), campaigned to provide education for women. IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution Preview Britain and British North America The American Revolution The War Begins Foreign Support and British Defeat Pgs. 320 - 321 IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution D. Britain and British North America The United Kingdom of Great Britain was a constitutional monarchy. Parliament had the power to raise taxes, create an army, and make laws. The monarch could appoint government ministers and set foreign policy. When the last Stuart monarch, Queen Anne (1665 – 1714), died, the throne passed to her nearest cousin. George I (1660 – 1727), Elector of Hanover, was a German who spoke no English. He and his son, George II (1683 – 1760), had little idea how the government worked, so they let their prime ministers run the nation. Robert Walpole (1676 – 1745) attempted to follow a course of peace. Under influence from the growing mercantile class, William Pitt the Elder (1708 – 1778) was nominated in 1757. He expanded the Empire in India and the Americas. The populous, prosperous American colonies were technically run by the British government, but in practice they exercised a great deal of autonomy. The colonists resented governmental interference. George I Pitt the Elder IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution E. The American Revolution “O! the fatal Stamp” Stamp riot in New Hampshire The Seven Years’ War had been extremely expensive for the British government. In order to recover some of the cost, and pay for the standing army left to protect the American colonies, Parliament decided to increase taxes on the colonists. The British government imposed the Stamp Act in 1765. This was a modest tax on printed documents, such as legal notices and newspapers. The American colonists, who were highly literate, took exception to the tax. The Stamp Act was so unpopular that it was repealed in 1766. It had established two patterns, though: The British government would make several more attempts to tax goods in the Colonies, and the American colonists would resist “taxation without representation” with violent determination. IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution F. The War Begins Several more tax crises followed. In 1774, the colonists had become so infuriated with the Crown that they organized the first Continental Congress in Philadelphia to raise militias. In April, 1775, fighting broke out between colonists and the British army around Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. A second Congress was held, and George Washington was nominated as commander-in-chief of Colonial forces. Another year passed before independence was declared on July 4, 1776. The Declaration of Independence, written by Thomas Jefferson (1743 – 1826) and based on the ideas of John Locke, formally made the colonies free from British authority. War had been declared. The Americans initially had no real hope of winning. The British army was large and professional, and their navy was the greatest in the world. By contrast, the Continental Army was untrained and underequipped, and the American navy did not yet exist. Declaration of Independence John Paul Jones IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution G. Foreign Support and British Defeat Marquis de Lafayette Surrender at Yorktown The Americans would have had no hope of defeating the British Empire had they not received assistance from other European powers. France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic all assisted the Colonial cause. The French, in particular, wanted to avenge their embarrassing defeat at the hands of the British in the Seven Years’ War. They supplied the Americans with money, weapons, military advisors and naval support. In 1778, France was the first nation to formally recognize American independence. In 1781, the British commander Lord Cornwallis (1738 – 1805) found himself surrounded at Yorktown. Cut off on land by the Continental Army and at sea by the French navy, Cornwallis was forced to surrender. This ended formal hostilities. In 1783, Britain signed the Treaty of Paris, which recognized the United States and ceded control of all territory to the Mississippi River. IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution Preview The Birth of a New Nation The Constitution The Bill of Rights Pgs. 321 - 322 IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution H. The Birth of a New Nation At the close of the war, the thirteen colonies were free. However, they had come to distrust centralized government, so they remained technically separate from one another. The first governing document of the United States, the Articles of Confederation of 1781, did not provide for a strong central government. It created the office of president of Congress, but the position had no authority. The government could not collect taxes, raise an army, or manage trade between the states. It was soon clear that the Articles were insufficient. In 1787, 55 representatives of the thirteen states met in Philadelphia to decide on a new system of government. This meeting became known as the Constitutional Convention. IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution I. The Constitution The proposed Constitution would set up a federal system, in which the central government and the states would share power. The central government would have the authority to raise taxes, create an army, control interstate commerce, and establish a national currency. Following the ideas of Montesquieu, the new government would have three branches: the Executive, the Legislative, and the Judicial. These three offices would regulate one another through checks and balances. The Executive is the president and his advisors. They enforce the laws, veto the legislature, nominate judges and command the military. The Legislative branch is the Senate and House of Representatives. They make the laws, approve nominations and control taxation. The Judicial is the Supreme Court. They decide the constitutionality of laws and enforce the Constitution. The Constitution had to be approved by each one of the states. In some cases, it was a close call, but all thirteen ratified it by 1788. IV. Colonial Empires and the American Revolution J. The Bill of Rights In order to get the Constitution ratified in all thirteen states, the Constitutional Convention had to promise to include a Bill of Rights. Twelve amendments were proposed, and ten were approved by the states. These first ten amendments guarantee a number of basic rights. Among them are the right to freedom of speech, religion, petition, press, and assembly. They also guarantee the right to bear arms, protection against unreasonable search and seizure, right to trial by jury, due process of law, protection from cruel and unusual punishment, and property rights. The Bill of Rights is partially based on the ideals of eighteenth century philosophes like Locke and Montesquieu. Enlightenment thinkers saw the American Revolution as the fulfillment of their intellectual prophesy, and the beginning of a new, rational age. The Bill of Rights Authors of the Federalist Papers