Obeah and Vodoo

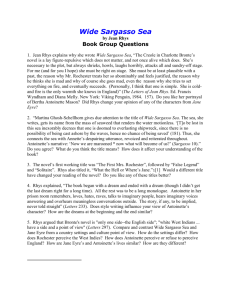

advertisement

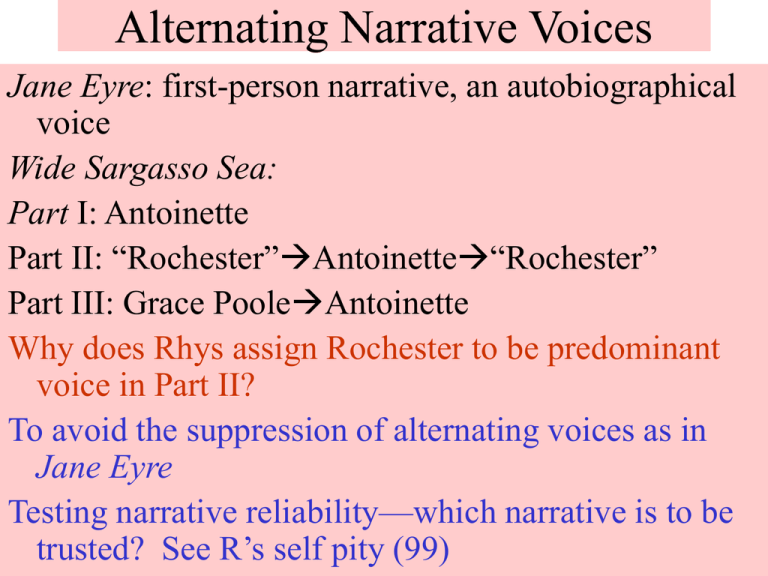

Alternating Narrative Voices Jane Eyre: first-person narrative, an autobiographical voice Wide Sargasso Sea: Part I: Antoinette Part II: “Rochester”Antoinette“Rochester” Part III: Grace PooleAntoinette Why does Rhys assign Rochester to be predominant voice in Part II? To avoid the suppression of alternating voices as in Jane Eyre Testing narrative reliability—which narrative is to be trusted? See R’s self pity (99) Two Quotes about Christophine • Spivak on imperialism: “Christophine is tangential to this narrative. She cannot be contained by a novel which rewrites a canonical English text within the European novelist tradition in the interest of the white Creole rather than the native.” (p.246) • Parry on Spivak: “what Spivak’s strategy of reading necessarily blots out is Christophine’s inscription as the native, female, individual Self who defies the demands of the discriminatory discourses impinging on her person.” (p.248) Christophine: Between Imperialism and the Native Voice Analyze the powerful presence of Christophine. How does Rhys describe her appearance and her linguistic competence? What is the significance of the fact that she disappears before the end of the novel? Gayatri Spivak and Benita Parry have very different view of Christophine. What is your stand in this argument and why? • Two major scenes of Christophine in WWS • Christophine and Antoinette (p.64-71) • Christophine and Rochester (p.90-97) Christophine and Antoinette • A surrogate mother for Antoinette—giving Antoinette advice, singing her to sleep—kiss her (90)– a human touch that softens A, who has been rejected by everyone else—see the “sun” in Antoinette • A model of self-independence for Antoinette • Antoinette depends on Christophine but still cannot get out of the racial stereotypes internalized by the white people—calling C “damned black devil from Hell” (81) Christophine and Rochester • multiple tongues —speaking French patois, English, and the native language vs the monolingual Rochester • The native talks back: judging R (92)--No longer a mimicking parrot (cf Annette’s parrot Coco)—force Rochester to repeat her words— a reversal of the colonizer/ colonized role in which the colonized is mimicking the master’s metropolitan language and discourse • A site of alternative power—an obeah woman Obeah and Voodoo Christophine as an obeah woman (a Nanny figure) --Antoinette’s fear--imagining the occult objects hidden in the room (p.18) --black people’s fear of her--Améle (p.61) -the love portion (p.82) and the sleep medicine for Antoinette (p.91) • Obeah as a part of Caribbean existence --a creolized practice of African religions and Christianity (memory of Africa)--negative + positive --negative: evil magic (esp. for the white colonizers) --positive: as a source of rebellion against slavery (ex. Nanny and the Maroons in Jamaican legends) Obeah as Metaphors in WWS • letter to Francis Wyndham (4/14/1964) p.138-9 Rhys’s “writer’s cramp” and the help from “Obeah Night” about R’s reason for hating A (1413)--a poem written in the name of Edward Rochester or Raworth--“I think there were several Antoinettes and Mr Rochesters. Indeed I am sure…. Mr R.’s name ought to be changed…. In the poem (if it’s that) Mr Rochester (or Raworth) consoles himself or justifies himself by saying that his Antoinette runs away after the “Obeah nights” and that the creature who comes back is not the one who ran away…. Antoinette herself comes back but so changed that perhaps she was ‘lost Antoinette’.” (140) Zombie and colonialism • Definition of zombie (64): symbolic of social and individual alienation • Antoinette turning into a ghost (102)—the haunting ghost in Thornfield (111)—”Her ‘real’ death is her subjugation by Rochester—by the colonizer—the long slow process of her reduction to the zombi state chronicled in the novel” (Sandra Drake 200) New Orleans Voodoo Museum • zombies humfo altar Names • name and identity--the African belief in name (88) • Daniel Cosway--Esau (73) ( sb. cheated out of his birthright) /Is he a Cosway—Daniel Boyd? (77, 94)—the importance of claiming the family name • Antoinette Bertha (68, 81, 88, 106-7) Marionette (90, 92, 103)--Why does Rochester change her name and the significance of this change of names? What is the significance in calling her Marionette (a doll)? • the unnamed male narrator in Part II (‘the man in Part III--Why does she keep him unnamed? (Why does she want to have him sign his name in “Obeah Night”?) Love, Sex, Betrayal and Hatred • signs of betrayals--cock crowing (40, 71, 97-98) • Rochester’s affair with Améle--People around Rochester and change their attitudes toward him after this one-nigh-stand Améle, Baptiste (85), Antoinette--physically transformed (87)—R feels everything as “hostile” (90) • His double standards: promiscuity (84, 88, 99) • R’s possessiveness: “my lunatic” (99) • Rochester’s hatred (83, 102-3) // (143) • the untold/undeveloped love story between Antoinette and Sandi (30)--hints at their sexual relationship (72-3, 75, 109-10)--white dress (76) for Rochester and red dress for Sandi (109) Spaces: the Caribbean vs. England • different gardens: Coulibri and Granbois “enclosed garden” (p.36) • Rhys’s one-room heroines—the final limit of hopelessness Antoinette has not locked herself up—for Grace it’s a shelter against the black and cruel world (105-6) • Places without looking glass: the convent (32), the house in England (107, 112)—What is the significance of looking glass? • England as world “made of cardboard” (107) What is the significance of this metaphor? Why does Antoinette insist that she has lost her way to England? Questions about the Ending • What are the significances of the red dress in Part III? (109) • Compare the fire scene in Part I and that in Antoinette’s dream in part III. Is there a parallel between the parrot in the first fire and Antoinette in the second? • What is the significance of the ending of the novel? Critics have argued that this novel has an open ending. Is Antoinette mad? Can she escape from the narrative containment? Has she burned down the house? The Ending The red dress—the color of fire and the flamboyant tree, the smell of the WI—a symbol of her Caribbean identity and of her memory of Sandi (109-10) vs the gray wrapper (110)—the color of England and sign of R’s neglect The two fires: Fire brings back her child hood memory (111-2)—the ambivalent power of fire—warm, purifying, protective but scorching (112) Holding the candle down the passage—a conformity to and a reversal of the Victorian angel in the house—illuminating, destructive—breaking her state of zombification (202)