Lecture 18 – results of Tuesday's experiment

advertisement

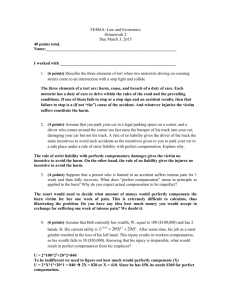

Econ 522 Economics of Law Dan Quint Fall 2009 Lecture 18 Results of Tuesday’s experiment 1 Tuesday’s experiment You have been asked to serve on a jury on a lawsuit dealing with personal injury. In the case before you, a 50-year-old construction worker was injured on the job due to the negligence of his employer. As a result, this man had his right leg amputated at the knee. Due to this disability, he cannot return to the construction trade and has few other skills with which he could pursue alternative employment. The negligence of the employer has been firmly established, and health insurance covered all of the related medical expenses. Therefore, your job is to determine how to compensate this worker for the loss of his livelihood and the reduction in his quality of life. 2 What did you all say a leg was worth? 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% less than 100,000 100,000 to 199,999 200,000 to 499,999 500,000 to 999,999 1,000,000 to 2,000,000 to 4,000,000 to 1,999,999 3,999,999 7,999,999 8,000,000 and up 3 What were we actually trying to test? Half of you were asked… The other half were asked… (a) Should the plaintiff in this case be awarded more or less than $10,000? (a) Should the plaintiff in this case be awarded more or less than $10,000,000? (b) How much should the plaintiff receive? (Please give a number.) (b) How much should the plaintiff receive? (Please give a number.) (c) (c) Are you male or female? Are you male or female? The question: how much did the “suggestion” affect answers to question (b)? 4 So, how much did question (a) affect your answers to question (b)? 35% asked 10k asked 10MM 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% less than 100,000 100,000 to 199,999 200,000 to 499,999 500,000 to 999,999 1,000,000 to 2,000,000 to 4,000,000 to 1,999,999 3,999,999 7,999,999 8,000,000 and up 5 Or to put it another way… Asked $10,000 Sample Size Asked $10,000,000 Both Groups 23 25 48 1,002,609 4,644,000 2,899,167 323,118 2,764,049 988,266 10,001 700,000 10,001 25th Percentile 112,500 1,000,000 250,000 Median 250,000 3,000,000 1,000,000 75th Percentile 875,000 5,000,000 3,100,000 10,000,000 20,000,000 20,000,000 Average Geometric Mean Smallest Largest 6 But the picture’s so cool, I’ll show it again 35% asked 10k asked 10MM 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% less than 100,000 100,000 to 199,999 200,000 to 499,999 500,000 to 999,999 1,000,000 to 2,000,000 to 4,000,000 to 1,999,999 3,999,999 7,999,999 8,000,000 and up 7 What does it mean? Nobody knows what a leg is worth “Reference point bias” “Framing effects” 8 Back to work… 9 So far… We’ve discussed a bunch of liability rules No liability Strict liability Various versions of a negligence rule And the effect of each rule on several incentives: Injurer precaution Victim precaution Injurer activity level Victim activity level And we saw the Hand Rule for determining negligence “If more precaution would have been efficient, you should have taken it” 10 Strict liability versus negligence Negligence rules lead to efficient precaution by both sides But strict liability leads to efficient activity level by injurers Over course of 1900s, strict liability rules became more common Why? 11 Strict liability versus negligence: information Relatively easy to prove harm and causation Harder to prove negligence If negligence is hard enough to prove, injurers might avoid liability altogether… …in which case they have no incentive to take precaution “Negligence requires me to figure out the efficient level of care for Coca-Cola; strict liability only requires Coca-Cola to figure out the efficient level of care” 12 Errors and uncertainty in evaluating damages Random mistakes Damages could be set too high or too low, but on average are correct Textbook calls these uncertainty Systematic mistakes Damages are set incorrectly on average – consistently too high, or consistently too low Textbook calls these errors 13 Effect of errors and uncertainty under strict liability Strict liability rule: injurer minimizes wx + p(x) D Perfect compensation: D = A Leads injurer to minimize social cost wx + p(x) A Under strict liability, random errors in damages have no effect on incentives Injurer only cares about expected level of damages As long as damages are right on average, injurers still internalize cost of accidents, set efficient levels of precaution and activity 14 Effect of errors and uncertainty under strict liability $ wx + p(x) D p(x) D wx + p(x) A wx p(x) A x x* Precaution (x) 15 Effect of errors and uncertainty under strict liability Under strict liability: random errors in setting damages have no effect systematic errors in setting damages will skew the injurer’s incentives if damages are set too low, precaution will be inefficiently low if damages are set too high, precaution will be inefficiently high failure to consistently hold injurers liable has the same effect as systematically setting damages too low if not all injurers are held liable, precaution will be inefficiently low 16 What about under a negligence rule? $ wx + p(x) D wx + p(x) A p(x) D wx p(x) A xn = x* x Under a negligence rule, small errors in damages have no effect on injurer precaution 17 What about errors in setting xn? $ wx + p(x) A wx p(x) A xn x* xn x Under a negligence rule, injurer’s precaution responds exactly to systematic errors in setting the legal standard 18 What about random errors in setting xn? $ wx + p(x) A wx p(x) A x* x x Under a negligence rule, small random errors in the legal standard of care lead to increased injurer precaution 19 To sum up the effects of errors and uncertainty… Under strict liability: random errors in setting damages have no effect systematic errors in setting damages will skew the injurer’s incentives in the same direction failure to consistently hold injurers liable lead to less precaution Under negligence: small errors, random or systematic, in setting damages have no effect systematic errors in the legal standard of care have a one-to-one effect on precaution random errors in the legal standard of care lead to more precaution So… when court can assess damages more accurately than standard of care, strict liability is better when court can better assess standards, negligence is better when standard of care is vague, court should err on side of leniency 20 What about relative administrative costs of the two systems? Negligence rules lead to longer, more expensive trials Simpler to just prove harm and causation But negligence rules lead to fewer trials Not every victim has a case, since not every injurer was negligent Unclear which system will be cheaper overall 21 Does it all matter? 22 Gary Schwartz, Reality in the Economic Analysis of Tort Law: Does Tort Law Really Deter? Reviews a wide range of empirical studies Finds: tort law does affect peoples’ behavior, in the direction the theory predicts… …but not as strongly as the model suggests 23 Gary Schwartz, Reality in the Economic Analysis of Tort Law: Does Tort Law Really Deter? Reviews a wide range of empirical studies Finds: tort law does affect peoples’ behavior, in the direction the theory predicts… …but not as strongly as the model suggests Most academic work either… took the model literally, or pointed out reasons why model was wrong and liability rules might not affect behavior at all Schwartz found truth was somewhere in between 24 Gary Schwartz, Reality in the Economic Analysis of Tort Law: Does Tort Law Really Deter? “Much of the modern economic analysis, then, is a worthwhile endeavor because it provides a stimulating intellectual exercise rather than because it reveals the impact of liability rules on the conduct of real-world actors. Consider, then, those public-policy analysts who, for whatever reason, do not secure enjoyment from a sophisticated economic proof – who care about the economic analysis only because it might show how tort liability rules can actually improve levels of safety in society. These analysts would be largely warranted in ignoring those portions of the law-and-economics literature that aim at finetuning.” 25 Gary Schwartz, Reality in the Economic Analysis of Tort Law: Does Tort Law Really Deter? Worker’s compensation rules in the U.S. Employer is liable – whether or not he was negligent – for economic costs of on-the-job accidents Victim still bears non-economic costs (pain and suffering, etc.) “…Worker’s compensation disavows its ability to manipulate liability rules so as to achieve in each case the precisely efficient result in terms of primary behavior; It accepts as adequate the notion that if the law imposes a significant portion of the accident loss on each set of parties, these parties will have reasonably strong incentives to take many of the steps that might be successful in reducing accident risks.” 26 Relaxing the assumptions of our model 27 Our model thus far has assumed… So far, our model has assumed: People are rational There are no regulations in place other than the liability rule There is no insurance Injurers pay damages in full They don’t run out of money and go bankrupt Litigation costs are zero We can relax each assumption and see what happens 28 Assumption 1: Rationality Behavioral economics: people systematically misjudge value of probabilistic events Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk” 45% chance of $6,000 versus 90% chance of $3,000 Most people (86%) chose the second 0.1% chance of $6,000 versus 0.2% chance of $3,000 Most people (73%) chose the first But under expected utility, either u(6000) > 2 u(3000), or it’s not So people don’t actually seem to be maximizing expected utility And the “errors” have to do with how people evaluate probabilities 29 Assumption 1: Rationality People seem to overestimate chance of unlikely events with well-publicized, catastrophic events Freakonomics: people fixate on exotic, unlikely risks, rather than more commonplace ones that are more dangerous 30 Assumption 1: Rationality People seem to overestimate chance of unlikely events with well-publicized, catastrophic events Freakonomics: people fixate on exotic, unlikely risks, rather than more commonplace ones that are more dangerous How to apply this: accidents with power tools Could be designed safer, could be used more cautiously Suppose consumers underestimate risk of an accident Negligence with defense of contributory negligence: would lead to tools which are very safe when used correctly But would lead to too many accidents when consumers are irrational Strict liability would lead to products which were less likely to cause 31 accidents even when used recklessly Assumption 1: Rationality Another type of irrationality: unintended lapses “Many accidents result from tangled feet, quavering hands, distracted eyes, slips of the tongue, wandering minds, weak wills, emotional outbursts, misjudged distances, or miscalculated consequences” 32 Assumption 2: Injurers pay damages in full Strict liability: injurer internalizes expected harm done, leading to efficient precaution But what if… Harm done is $1,000,000 Injurer only has $100,000 So injurer can only pay $100,000 But if he anticipates this, he knows D << A… …so he doesn’t internalize full cost of harm… …so he takes inefficiently little precaution Injurer whose liability is limited by bankruptcy is called judgment-proof One solution: regulation 33 Assumption 3: No regulation What stops me from speeding? If I cause an accident, I’ll have to pay for it Even if I don’t cause an accident, I might get a speeding ticket Similarly, fire regulations might require a store to have a working fire extinguisher When regulations exist, court could use these standards as legal standard of care for avoiding negligence Or court might decide on a separate standard 34 Assumption 3: No regulation When liability > injurer’s wealth, liability does not create enough incentive for efficient precaution Regulations which require efficient precaution solve the problem Regulations also work better than liability when accidents impose small harm on large group of people 35 Assumption 4: No insurance We assumed injurer or victim actually bears cost of accident When injurer or victim has insurance, they no longer have incentive to take precaution But, insurance tends not to be complete 36 Assumption 4: No insurance If both victims and injurers had complete insurance… Neither side would bear cost of accidents If insurance markets were competitive, premiums would exactly balance expected payouts (plus administrative costs) We said earlier, goal of tort law was to minimize sum of accidental harm, cost of preventing accidents, and administrative costs In a world with universal insurance and competitive insurance markets, goal of tort law can be described as minimizing cost of insurance to policyholders Under strict liability, only injurers need insurance; under no liability, only victims need insurance 37 Assumption 4: No insurance Insurance reduces incentive to take precaution Moral hazard Insurance companies have ways to reduce moral hazard Deductibles, copayments Increasing premiums after accidents Insurers may impose safety standards that policyholders must meet 38 Assumption 5: Litigation costs nothing If litigation is costly, this affects incentives in both directions If lawsuits are costly for victims, they may bring fewer suits Some accidents “unpunished” less incentive for precaution But if being sued is costly for injurers, they internalize more than the cost of the accident So more incentive for precaution A clever (unrealistic) way to reduce litigation costs At the start of every lawsuit, flip a coin Heads: lawsuit proceeds, damages are doubled Tails: lawsuit immediately dismissed Expected damages are the same same incentives for precaution But half as many lawsuits to deal with! 39