Econ 522 – Lecture 17 (Nov 11 2008)

advertisement

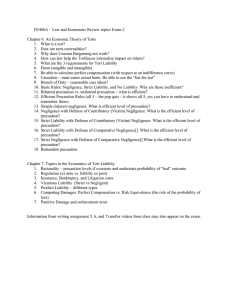

Econ 522 – Lecture 17 (Nov 11 2008) HW 3 posted online – due Thursday after Thanksgiving midterm graded – will return end of lecture Last week, we introduced a model of unilateral precaution, and looked at the effect various liability rules have on both injurer and victim behavior. In particular, we found that: a rule of no liability leads to inefficiently low injurer precaution, as well as inefficiently high injurer activity, since he does not internalize the cost of accidents; but it leads to efficient behavior by victims, since they face the full cost of accidents a rule of strict liability leads to efficient behavior by injurers, since they bear the cost of accidents; but it leads to inefficiently low victim precaution, and inefficiently high victim activity, since they are fully compensated for accidents and therefore do not consider their costs a negligence rule, with the correct standard of care, can achieve the efficient level of precaution by either victim or injurer under a negligence rule, one party or the other remains the residual risk bearer (that is, pays the cost of any accidents that still occur despite efficient precaution); this party sets an efficient activity level, while the other party still sets an inefficiently high level of activity The Shavell paper, “Strict Liability versus Negligence,” calls the cases we’ve been looking at “accidents between strangers”. That is, when a car hits a bicyclist, there is no preexisting relationship between the two parties. However, Shavell also looks at cases where the injurer is a business, engaged in selling some product (either to the victim or to someone else). Under the assumption of competitive markets, this changes the story significantly. Shavell assumes it is only injurer precaution that affects the likelihood of accidents. He looks at a number of different cases. (Under injurer precaution, a rule of no liability is obviously bad, so he focus on comparing negligence to strict liability.) He assumes there is no insurance. First, as we’ve already seen, is the case of accidents between strangers – or as he puts it, “injurers and victims are strangers, neither are sellers of a product, and injurers may choose to engage in an activity which puts victims at risk” He gives a nice explanation of what happens under a simple negligence rule: “Under the negligence rule, all that an injurer needs to do to avoid the possibility of liability is to make sure to exercise due care if he engages in his activity. Consequently he will not be motivated to consider the effect on accident losses of his choice of whether to engage in his activity or, more generally, of the level at which to engage in his activity; he will choose his level of activity in accordance only with the personal benefits so derived. But surely any increase in his level of activity will typically raise expected accident losses. Thus he will be led to choose too high a level of activity.” Under a strict liability rule, on the other hand: “Because an injurer must pay for losses whenever he is involved in an accident, he will be induced to consider the effect on accident losses of both his level of care and his level of activity. His decisions will therefore be efficient. Because drivers will be liable for losses sustained by pedestrians, they will decide not only to exercise due care in driving but also to drive only when the utility gained from it outweighs expected liability payments to pedestrians.” We can start our table again, focusing only on injurer precaution and injurer activity: ACCIDENTS BETWEEN STRANGERS Liability Rule Seller Precaution Simple Negligence Efficient Strict Liability Efficient Seller Activity Too High Efficient Next, Shavell considers accidents between sellers and strangers – that is, injurers are engaged in some sort of competitive business, but not with their victims He gives the example of taxi drivers – taxis provide a service to passengers, but still run the risk of hitting other pedestrians who aren’t their passengers Shavell assumes that there is perfect competition – taxis lower their prices to compete against each other, up till prices equal the costs of “production”; and the number of passengers who demand rides at those prices determine the level of sales Under a strict liability rule, the outcome is still efficient, but for a different reason Under strict liability, taxi drivers pay for accidents, so they will take the efficient level of precaution In addition, the expected costs of remaining accidents is borne by the taxi drivers, so under competition, it is built into the price of a taxi ride (That is, once taxi fares reach the level that just covers costs plus expected damage payments, taxi drivers stop lowering prices, so that sets the price.) This means that taxi passengers face the “socially optimal” price – given efficient precaution, they now internalize the cost of accidents, so they take the efficient number of taxi rides Under a negligence rule, the activity level is still inefficiently high, but again, for a different reason Under a negligence rule, taxi drivers take efficient precaution, to avoid liability for any accidents that occur But once they’re taking efficient precaution, they’re no longer liable, so they do not bear the costs of accidents So the cost of accidents is not built into prices So passengers face prices that are too low – taxi passengers don’t internalize the cost of accidents when they decide how often to ride So the demand for taxi rides will be inefficiently high – again, we get an inefficiently high activity level So the table looks the same as before: Liability Rule Seller Precaution Seller Activity ACCIDENTS BETWEEN STRANGERS Simple Negligence Efficient Too High Strict Liability Efficient Efficient ACCIDENTS BETWEEN SELLERS AND STRANGERS Simple Negligence Efficient Too High Strict Liability Efficient Efficient The third case that Shavell considers is that of accidents between sellers and their customers (or their employees) Here, he uses the example of restaurants taking precautions to reduce the risk of food poisoning In this case, it ends up vitally important how accurately customers perceive risks He looks at three separate cases: o customers can accurately perceive the risk of each restaurant o customers can accurately perceive the average level of risk, but not differences between different restaurants o customers are just generally ignorant of the risks Under strict liability, customer perception of risk ends up not mattering after all Under strict liability, the seller bears the cost of accidents, so he takes efficient precaution to prevent them And since he still bears the remaining risk of accidents, their expected cost is built into the price of meals – that is, menu prices include a premium for expected damage payments when food poisoning does occur Which means that regardless of whether they perceive risk, customers make efficient choices about how often to eat out, because they explicitly see the cost of risk through prices (That is, if I like seafood, I don’t have to know that if I eat raw shellfish, I have a 1-in-100 chance of an unpleasant experience that costs me $500; I don’t need to know this because the cost of a raw shellfish meal is $5 more than it would be otherwise, since the restaurant needs to charge this just to break even since if I ever do get sick, he knows I’ll sue. So the prices I face include the expected cost of food poisoning; so even if I don’t realize that, I choose efficiently.) Under negligence, however, this doesn’t work Under negligence, restaurants will still take efficient precaution, to avoid liability (they’ll keep the kitchen clean, wash hands after using the bathroom, etc.) But since they then won’t be liable when accidents do occur, prices won’t reflect these risks If customers correctly perceive risks, this won’t matter – customers will consider the money cost of the meal, plus the expected cost due to food poisoning, and will choose efficiently But if customers underestimate the risk of food poisoning, they’ll order an inefficiently large number of risky meals – the level of activity will be too high We can start a new table, just for the case of sellers and their customers: Liability Rule Risk Perception Seller Buyer Activity Precaution Strict Liability Yes Efficient Efficient No Efficient Efficient Negligence Yes Efficient Efficient No Efficient Too High We can also look at what will happen under a rule of no liability If customers correctly judge the risk, then sellers will still take efficient precaution – it gives them a way to attract customers If the restaurant can spend $3 to make a meal $5 cheaper in expected costs, they could charge $4 more for the meal and still get more customers. Competition means that this will happen So if risk is judged accurately, sellers will take efficient precautions, and buyers, judging risk correctly, will buy the efficient number of meals Next, suppose customers can accurately judge the average level of risk across all restaurants, but can’t differentiate between restaurants In this case, restaurants have no reason to take precaution – since they won’t be rewarded with higher sales, and they won’t be liable if there are accidents – so precaution will be zero But, at least customers will know that precaution is low and the product is risky, so they’ll eat the efficient number of meals (Under no liability in a city without any health inspectors, maybe people don’t eat much sushi.) Finally, consider the case where customers are just completely oblivious to the risk of the product Like the last case, there is no reason for sellers to take any precaution And since there is no liability, risk will not be built into prices And since customers can’t perceive risk, not only is precaution too low, but activity is too high – customers don’t consider the risks when deciding how often to eat out So for the case of accidents between sellers and their customers, we can sum up Shavell’s results like this: ACCIDENTS BETWEEN SELLERS AND THEIR CUSTOMERS Liability Rule Risk Perception Seller Buyer Activity Precaution Strict Liability Yes Efficient Efficient No Efficient Efficient Negligence Yes Efficient Efficient No Efficient Too High No Liability Yes Efficient Efficient Average None Efficient No None Too High (They also argue accidents between businesses and their employees work the same way.) It’s a really nice paper. At least read the introduction if you’re fuzzy about all this. Next topic: due care. All our talk about negligence rules, and especially about efficiency, has assumed that courts are able to set a legal standard of care equal to the efficient level That is, a negligence rule leads to an actual level of precaution equal to the legal standard x~. Efficiency requires this to match the level that minimizes the total social cost of accidents, x*. So negligence rules are only efficient if x~ = x*. In some cases, this is exactly what the courts try to do. This is based on a 1947 case, United States v Carroll Towing Company, in which Judge Learned Hand formulated a rule for deciding on negligence. The case (as described in Cooter and Ulen) was this: A number of barges [in New York Harbor] were secured by a single mooring line to several piers. The defendant’s tug was hired to take one of the barges out to the harbor. In order to release the barge, the crew of the defendant’s tug, finding no one aboard in any of the barges, readjusted the mooring lines. The adjustment was not done properly, with the result that one of the barges later broke loose, collided with another ship, and sank with the cargo. The owner of the sunken barge sued the owner of the tug, claiming that the tug owner’s employees were negligent in readjusting the mooring lines. The tug owner replied that the barge owner was also negligent because his agent, called a “bargee,” was not on the barge when the tug’s crew sought to adjust the mooring lines. The bargee could have assured that the mooring lines were adjusted correctly. Judge Learned Hand, in his decision, wrote the following: It appears from the foregoing review that there is no general rule to determine when the absence of a bargee or other attendant will make the owner of a barge liable for injuries to other vessels if she breaks away from her moorings… Since there are occasions when every vessel will break away from her moorings, and since, if she does, she becomes a menace to those around her; the owner’s duty, as in other similar situations, to provide against resulting injuries is a function of three variables: (1) the probability that she will break away; (2) the gravity of the resulting injury, if she does; (3) the burden of adequate precautions. Possibly it serves to bring this notion into relief to state it in algebraic terms: if the probability be called P; the injury, L; and the burden, B; liability depends upon whether B is less than L multiplied by P. Thus, Judge Hand argued that if precaution (in this case, having a bargee on board your barge) cost less than its expected benefit, then it was negligent not to do it. So the legal standard for what constituted negligence was whether the precaution was efficient. Since having an agent on board the barge is a yes-no decision, not a continuous variable, these were stated as absolutes; but if we reinterpret them as marginal terms, we get back to our old rule for efficiency: that if w, the marginal cost of precaution, is less than –p’A, the marginal benefit, the injurer is negligent. Implicitly, this is the same as setting the legal standard for care, x~, equal to the efficient level, x*. Cooter and Ulen argue that successive application of the Hand rule over time will lead to people figuring out what the legal standard for precaution is. I’m careless, I cause an accident, I get sued. The court rules that a little more precaution would have been justified, so I’m held liable. The next guy is a little more careful; an accident happens, he gets sued, he’s found negligent. The next guy is a little more careful. Eventually, we reach a level of care where a little bit more would not have been cost-justified; that guy is found not to be negligent, and not held liable, and then we all know what level of care is required. Another alternative, of course, is for laws and regulations to specify a legal standard. Highway officials could compute the efficient speed for a particular road – accounting for the value of getting somewhere sooner, and the effect of speed on the likelihood of accidents – and set the speed limit to the be efficient speed. And of course, a third alternative is for the law to enforce social norms or best-practices of an industry when it comes to standards of care. That is, if a community or an industry has been facing this problem for a long time, and evolved its own norms or practices for what level of care is required, it’s plausible that this level is efficient, and the court may just choose to enforce it. The book gives the example of a residential community setting rules concerning the maintenance of steps leading up to houses, or the accounting industry having standards regarding auditing. Cooter and Ulen point out that American courts have consistently made a mistake in the way they’ve applied the Hand rule. In terms of calculating the efficient level of precaution, marginal cost should be balanced against the total social benefit of reducing accidents, which includes both the reduction in risk to the plaintiff (“risk to others”) and the risk to the injurer himself (“risk to self”). For example, when I drive recklessly, I risk hitting a pedestrian, and I also risk destroying my own car. The reduction in both these risks constitutes the social benefit of driving more carefully. However, courts have tended to only consider the reduction in “risk to others” when assessing the benefits of precaution. Cooter and Ulen also point out the idea of “hindsight bias” – once something happens, we tend to assume it was likely to happen. That is, if something is extremely lowprobability, but then occurs, we may change our mind about how unlikely it initially was to happen. This would lead to an overestimate after the fact of the probability of an accident. Next, a little history. We’ve shown that a negligence rule creates efficient incentives for precaution by both the victim and the injurer, while a strict liability rule only creates efficient incentives for the injurer. However, over the course of the 1900s, the incidence of strict liability rules increased. Why? The answer has to do with information. It’s easy to prove harm and causation – my coke bottle explodes and takes out my left eye. Clearly, I got hurt; and clearly, the bottle did it. But it’s very hard to prove that Coca-Cola was negligent in their bottling process – I’d have to understand their whole manufacturing process, understand the likelihood of accidents, how the likelihood of accidents responds to precautionary measures they could have taken, how much those actions would have cost, and so on. Under a negligence rule, it might be too hard to prove negligence; and so the manufacturer might not have to take precautions, knowing they can avoid liability anyway. On the other hand, under strict liability, the company bears the cost of accidents, so it faces the incentive to reduce accidents directly, not just avoid having appeared negligent. To put it another way, negligence requires me to figure out the efficient level of care Coca-Cola should have taken; strict liability requires Coca-Cola to figure out the efficient level of care. If Coca-Cola has better knowledge of their manufacturing process than I do, this may be better. This leads us to the topic of errors and uncertainty in evaluating damages, and the effects that these have on incentives for precaution. First, put aside the question of whether or not someone is liable, and think only about the problem of calculating the amount of damages owed. There are two types of mistakes a court can make: systematic mistakes, and random mistakes. Random mistakes mean that, if an accident caused $10,000 in harm, the court might end up setting damages either higher or lower than $10,000, but on average will get it right. (DRAW IT.) Systematic mistakes are when damages, on average, are set either higher or lower than the actual harm. C and U refer to systematic mistakes as “errors,” and to random mistakes as “uncertainty”. First, let’s look at the effects of errors under a strict liability rule. Under a strict liability rule, the injurer minimizes the sum of two things: cost of precaution, plus expected damage payments. (With perfect compensation, damage payments = cost of accidents, and so the injurer minimizes the total social cost of accidents.) Random errors in damages awarded have no effect on injurer incentives under a strict liability rule. This is because the injurer is only concerned with the expected level of damages he will have to pay; as long as damages are right on average, he will still internalize the expected cost of accidents, and still take the same level of precaution. On the other hand, systematic errors in calculating damages will skew the injurer’s incentives. If damages are consistently set too low, then the injurer will not internalize the entire social cost of accidents; so precaution will be set too low. (DRAW IT.) If damages are consistently set too high, the injurer will internalize more than 100% of the social cost of accidents, so precaution will be set too high. To sum up, under strict liability, systematic errors in setting damages will cause the injurer’s precaution level to respond in the same direction as the error; random errors in setting damages will have no effect. Another way the court could err is to fail to find the injurer liable when it should. If the probability of being found liable is less than 100%, this has the same effect as lowering the expected level of damages that the injurer has to pay. (The injurer is indifferent between paying $10,000 in damages half the time, or paying $5,000 in damages for sure.) So a failure to consistently hold injurers liable has the same effect as a systematic error in setting damages too low: Under strict liability, systematic errors in failing to hold injurers liable leads to less injurer precaution. Next, we can look at the same incentives under a negligence rule. (DRAW IT.) Here, the result is very different. Small errors in setting damages – either their amount, or whether they are awarded at all – will change how the injurer perceives the p(x)A curve. However, because of the discontinuity, small errors will not cause the injurer to change his behavior – it will still be optimal to take a precaution level of x~. So “modest” errors – either systematic or random – in setting damages will have no effect on precaution under a negligence rule. Under a negligence rule, modest errors in setting damages will not affect injurer precaution. Similarly, occasional failures to hold negligent injurers liable will also not affect injurer precaution, so long as they are occasional. (If you have a 90% chance of being held liable when negligent, it’s the same as being charged 90% of the proper level of damages; it probably isn’t enough to change your behavior under a negligence rule.) Of course, large enough errors in either measure could cause the p(x) D curve to dip below the level of w x*, in which case they would have an effect. (C and U also point out that these errors can be thought of as court errors in setting appropriate damages, or as injurer errors in predicting the level of damages. Again, neither one leads to a change in precaution level under a negligence rule, so long as the errors are not too large.) Of course, under a negligence rule, the court also has to rule on whether the legal standard of care was met, that is, the court has to compare the care the injurer took, x, to the legal standard, x~, which we hope is set equal to the efficient level, x*. Systematic errors in the standard of care have a very direct effect on injurer precaution. (DRAW IT) In general, under a negligence rule, the injurer’s level of precaution responds exactly to systematic court errors in setting the legal standard. What about random errors? Here, the result is a little bit harder to see. I don’t want to get into the technical details of it, small amounts of uncertainty about the legal standard will lead to firms taking higher precaution. That is (DRAW IT) In general, under a negligence rule, small random errors in the legal standard of care cause the injurer to increase precaution. Given these results, C and U argue that when courts are able to assess damages more accurately than standards of care, a strict liability rule is better; when a court can assess standards more accurately than damages, a negligence rule is better. Also, they point out that when the standard of care is vague, that is, when there is uncertainty about what does and does not constitute negligence, the court should err on the side of leniency, so as not to further aggravate the problem of excessive precaution. (The book does a little aside on “bright-line” rules, like speed limits, versus vague standards, like “don’t drive recklessly”. In certain settings, laws won’t be enforced if they’re overly vague. Off-topic a bit, but California helmet law.) (ENDED HERE, RETURNED MIDTERM) Cooter and Ulen talk a bit about the different costs of administering different liability systems. Obviously, it’s simpler to prove just harm and causation than to prove harm, causation, and negligence; so once a case goes to court, we expect the administrative costs to be higher under a negligence rule than under strict liability. (More time spent, more witnesses, etc.) On the other hand, under a negligence rule, many victims will know they have no case, and therefore not bring a lawsuit at all; under a strict liability rule, every accident victim is entitled to damages, so there will be more lawsuits. So strict liability will lead to more cases, but easier cases. Obviously, a rule of no liability leads to lower administrative costs than either, since there’s no work to be done. C and U also point out the tradeoff between rules (such as the legal standard of care) which are tailored to individual situations, versus broad, simple rules that apply to many situations. As we’d expect, broad, simple rules are cheaper to create and enforce, but will not create perfect incentives in every situation; more specific, detailed, “tailored” rules will be more costly to create and enforce, but will create more efficient incentives. In addition, there is the question of who bears some of these administrative costs. In some countries, victims who win at trial also have their legal expenses paid by the injurer; in the U.S., this tends not to be the case.