University Studies 15A: Consciousness I

advertisement

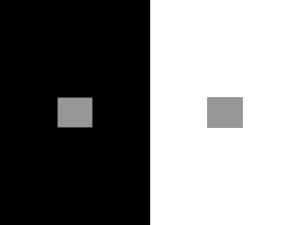

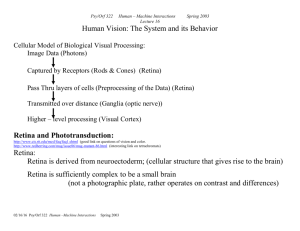

University Studies 15A: Consciousness I The Neurobiology of Vision The Neurobiology of Vision provides an example for the challenges of understanding consciousness. The first challenge is simply to grasp the problem biology presents. If we cannot see that visual awareness, whatever it is in the mind, is a reconstruction based on layer upon layer of processing in the brain, we will not see that there is a problem to be explained in the first place. We will not agree that the science matters in principle. We will not agree that the details of the neurobiology are relevant as a challenge to our experience of visual awareness. We will not agree that our experience of visual awareness is relevant as a challenge to getting the details of the neurobiology right. If we can come to see the neurobiology as relevant to the problem of visual experience, the next challenge is to synthesize the two levels of description. 1. Our account of visual experience must account for the neurobiology. a. It must account for the constructed character of visual awareness b. It must account for the particular details of the biological mechanisms 2. The neuroscientific account must respect the experiential facts of visual consciousness a. It must provide an account adequate to explain (at least roughly) the qualities of first person experience b. That is, it will need to integrate the visual system into a “self,” into semantic networks, memory, emotions, and saliency. We start this week with the visual system itself, not with its integration into other networks of meaning and memory. We will set out the layers of mediation, the biological sub-systems upon which visual experience is built. I hope you will agree that the biology of vision does indeed present a challenge to our understanding of visual consciousness. We start with the eye. We are not concerned with questions of optics. We want to know how the optical information is changed into neuronal responses. For this, we look at the retina. The retina has three basic layers: 1. On the surface of the retina, ganglion cells connect to the optic nerve. 2. In the middle, bipolar cells process responses of the rods and cones and pass activation to the ganglion for more aggregation. 3. Behind the other neurons are the rods and cones that are the photoreceptor cells. Photoreceptors: 1. The rods are not tuned for color but are sensitive, working well with low light The rods are not tuned for color but are sensitive, working well in low light There are many more rods than cones on the periphery of the retina, fewer near the fovea (see below) Photoreceptors: 2. The cones are tuned for three wavelengths of light, labeled “long,” “medium,” and “short” Horizontal Cells: These are a source of lateral inhibition for the rods and cones. The lateral inhibition begins the process of defining “center-surround” receptive fields. That is, given the right connections, if all the receptors surrounding a particular rod/cone are firing, the horizontal cells activated by those receptors may inhibit the central receptor. Or the other way around: the firing of the central receptor may inhibit the firing of its neighbors Bipolar Cells: There are rod bipolar cells and cone bipolar cells. There are none with synaptic connections to both. Rod bipolar cells are connected to amacrine cells rather directly to ganglion cells. Bipolar cells come in two types: “On” bipolar cells (which spike most quickly when photoreceptors indicate the presence of light) and “Off” bipolar cells (that spike most in the dark). Amacrine Cells: Seventy percent of the neurons connecting to the ganglion cell are amacrine cells. As noted, rod bipolar cells are connected to amacrine cells rather directly to ganglion cells. Amacrine cells seem to be involved in lateral inhibition among the bipolar cells However, amacrine cells remain something of a mystery after decades of work. Ganglion Cells: Ganglion cells gather data from a collection of bipolar cells that in turn have gathered data from a collection of rods or cones.. As a result, ganglion cells have a receptive field. They are either off-center on-surround or on-center off-surround. Baars and Gage show the response pattern for an “on-center off-surround” ganglion cell. The cell spikes at a moderate rate for weak on-center light (as determined by the photoreceptor data transmitted via the bipolar cells) and spikes strongly for strong oncenter light. The cell spikes slowly when there is some light in the “surround” and slowest for full light in the “surround” As Baars and Gage explain, the resulting spiking patterns turn the ganglion cells into neurons that respond most strongly to edges where information changes. Hence the retina performs a first level of data reduction that reorganizes the visual field: The axons of the ganglion cells form the optic nerve and transmit data that emphasizes edges. However, we still are not through with the design of the retina. At one place in the retina, the ganglion and bipolar cells have been pushed to the side to allow a concentration of cone cells to have particularly precise information about the light coming into the eye. This is the fovea: We can tract the center of visual attention by tracking the shifting of the fovea as it focuses on different part of a visual scene. This is foveation: The optic nerve then splits the visual data into right and left streams and carries the data to the contralateral (“other-side”) lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) in the thalamus As Baars and Gage note, the receptive fields of the neurons in the LGN are basically like those of the ganglion cells in the retina. That is, “On-center off-surround” and “Off-center on-surround” However, it is important to stress that 10% of the connections to the LGN come from the retina and 90% from V1 and other “up-stream” layers. The LGN must be performing types of signal enhancement based on previously extracted patterns at higher levels. We finally get to V1, the Primary Visual Cortex (this is a macaque brain) As we have discussed before, the simple cells of V1 extract line-segment information from the receptive-field activations sent from the LGN: Note that the “data” transmitted at each stage is in terms of spiking rates. However, beyond the “simple cells,” other cell assemblies in V1 extract other types of patterns and combinations of patterns. Some cell assemblies detect direction of motion (changes in light over a “retinal map” in V1). Some cell assemblies detect motion of line segments with particular angles. Since data is coming in from both eyes, some cell assemblies detect differences between the data provided by the two eyes (binocular disparities). Some cell assemblies add in color information based on comparing the spiking rate of L, M, and S cones. In all these systems, remember that the network of neurons work by difference, by dividing the incoming data into mutually differentiated, mutually inhibiting groupings. Onward and Upward: Beyond V1 Baars and Gage provide us with an excellent summary image: This is the so-called “What” Pathway, a.k.a. the Ventral Pathway The story starts to get a bit complicated as we head to higher areas. The dorsal stream, the “Where” pathway next goes to the “middle temporal area’” (MT). For the moment, however, follow the red arrows for the ventral pathway and remember that the “Where” pathway is the dorsal stream. We’ll explore what happens next to turn visual data into visual consciousness after the mid-term.