One Hundred Years of Evil Justin Douglas Outten David Clausen

advertisement

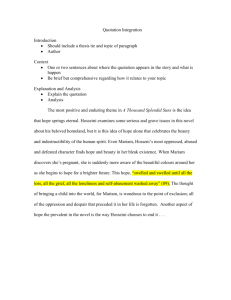

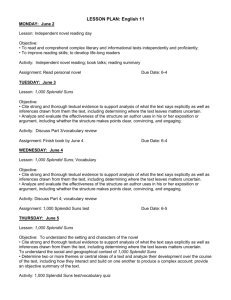

One Hundred Years of Evil Justin Douglas Outten David Clausen May 25, 2012 A3 AP English Gate to Auschwitz Concentration Camp 1 Prologue As hundreds of years passed, Dorian Henry, disgusted by the human race, realizes that the human race is the root of all evil. Cursed with immortality, Henry is forced to forever live life as a high-schooler. He is forced to outlive everyone he has ever known. He has witnessed friends and family die. He has witnessed nations rise, and he has witnessed nations fall. He has witnessed peace, and he has witnessed war. Dorian has had enough. He can’t keep his secret buried away any longer. He needs to tell someone. He chose to reveal his secret in his final essay: the iSearch. 2 I couldn’t stay in one place for more than four years; otherwise people would grow suspicious of my age. This time it was Seoul, South Korea. I was always on the move, and I could never settle somewhere for too long. I’ve lived through history’s worst years and its best. I’ve had my share of memories in Europe, the United States, the Middle East, and even Korea, (before it was separated.) I’ve lived all over the world but could never achieve comfort. My life was a curse. When I was a seventeen, I lived in a small rural town in Edinburgh, England. I can hardly remember if it was the seventeenth century or the eighteenth. Nonetheless, it was quite some time ago, but I remember it clearly. One night I was in the woods looking for firewood for my family, and suddenly, a gloomy aura filled the air behind me. I turned around, dropping the wood that I had gathered. I stood motionless as a black smoke covered me completely. The smoke left after a few moments. I was stunned. I remember how those few seconds in the smoke felt like years. I knew nothing of what had happened and told no one, for no one would believe me. Everyone would think I was crazy or some poor young soul that need an exorcism. A poor farm boy didn’t need any attention like that. After a number of years, I noticed something different about me, or, more specifically, absolutely nothing different. All my friends and family had shown signs of wear and age. Wrinkles became more apparent on foreheads; hair grew on chests; baby fat turned into muscle. But, not me. After 10 years, nothing about me had changed. I recalled the moment of my life when I was approached by the blackness. A crazy thought entered my mind: “I can’t age.” I tried committing suicide countless times, but to no 3 avail. My skin would heal instantly and my scars would bury away under new skin. Others around me kept aging, except me. My parents believed I was some demon, so they abandoned me. I had nowhere to go. I fled my rural hometown and began living life alone, surviving off what little money I could earn and going to schools to fit in. I’ve been all over the world. I’ve lived in Europe for almost a century, many decades in the Americas, a number of years in the Middle East, and now Asia. I survive by fitting in. I falsify my identity, and I enroll in schools and find a small place to live. Living in Seoul was my get away from the first world. I enrolled myself into a school that involves students coming and going every two years. I’ve been here for three years so far. I can’t remember how many times I’ve been a junior in high school. I don’t dare try and guess how many of my beloved teachers I’ve out-lived. However, this year was different. I was given an assignment to read four novels over the year and at the end, create an essay that synthesizes the books’ major themes and ideas. I wanted to make this one count, so I wrote about a time I was familiar with. A time I wanted to get past: the twentieth century. The twentieth century was the worst hundred years of the human race. Millions of people died and millions more were affected. I chose to study novels that focused on man’s inhumanity to man. I remember how women were treated like slaves just because they were believed to be inferior to men, shown in Khaled Hosseini’s book, A Thousand Splendid Suns. I remember when Korea was under turmoil and innocent people were sent to live in gulags for crimes they didn’t commit, represented in Kang Chol-Hwan’s The Aquariums of Pyongyang. I remember when the African-Americans were treated as 4 unequal and as second class citizens just because of the color of their skin, just like in Kathryn Stockett’s novel, The Help. I even remember the years where Hitler reigned in Europe and persecuted Jews and other non-Aryans and committed genocide, depicted in Elie Wiesel’s Night. I chose these books because of the themes that pertained to each book: hope, oppression, racism, inequality, injustice, and inhumanity. These six themes are the epitome of the dark twentieth century filled with horrors and death. I remember how each one of those themes played a part throughout the 1900s and throughout my four novels. I shared something in common with the authors of each novel. Although I was never in a concentration camp like Kang and Wiesel, I lived through the same era. I understood the sadness they felt when their friends and family died. I knew how it felt to be treated “like dogs” (17:22). A short memoir full of genuine sadness and inhumanity, Night, by Elie Wiesel, is about a young Jewish boy and his family who are “expelled” (17:3) with other “foreign Jews from Sighet,” (17:3) his hometown. Stripped of his identity and family, Eliezer, a fifteen year old boy, is disconnected from society and put into the Nazi Auschwitz concentration camp with his father. In this camp, Eliezer and his father are forced to sacrifice years of their life fighting for survival under constant oppression and inhumanity. As I read Night I remember the days I sat in the apartment cellar as bombs fell from the London night sky. The sound of rumors of genocide and “camps” still ring in my head: “Babies were thrown into the air and the machine gunners used them as 5 targets.” (17:4) I remembered walking down the streets as I saw people with a yellow star on their chests, matched with a look of sadness on their faces. The sadness in their faces could not hide behind a smile like the smiles of the help in Kathryn Stockett’s novel: The Help. Living in a small town like Jackson, Mississipi for many years, I understood how Aibileen and Minnie felt when their white overseers mistreated them daily. The Help was a story about a handful of women, black and white, who were subject to racism and sexism. In a racially segregated town like Jackson, many people were afraid to go against the tacit codes about black and white integration; however Skeeter, a rebellious college graduate, wasn’t. Through a series of interviews with black maids, Skeeter documents their confessions and creates a book that narrates their memories and hardships; filled with racism, inequality, and injustice, while working for white families as maids. Just like in The Help, Khaled Hosseini, a denizen of Afghanistan, writes a novel about the mistreatment of two women, Mariam and Laila, in a troublesome country and a difficult time period: the 1970s. Subject to discrimination and abuse, both girls are forced into an arranged marriage and must endure domestic abuse, poverty, starvation, and the Taliban. I once lived in small city like Kabul, and it was quite normal to see very young women partnered with much older men; results of arranged marriages. I can still see the miserable eyes that were left uncovered by the traditional burqa1. Tired of the extreme inequality and dangers, not only women, but everyone faced in the Middle East, I moved to a remote location: Korea. Believing I was away from 1 - a required veil to cover Islamic women’s faces. 6 genocide, from racial injustice, from domestic inhumanity, I lived life in the capital of communist North Korea: Pyongyang. I was among many who were oppressed by the state and forced to relinquish my personal possessions. I knew this place was no different than Auschwitz, Poland, Jackson, Mississippi, or Kabul, Afghanistan. Families like Kang’s were forced give up all that they owned to the Communist Party. Kang’s family, along with other unlucky, innocent families, was wrongfully tried and sentenced to ten years at Yodok’s labor camp. Disguised as a border patrol headquarters, Yodok’s true purpose was hidden to the public and the inhumane activities that occurred there were masked as well. Kang was forced to grow up quickly from the back-breaking labor and his indigent family. Almost everyone one of my characters were persecuted for something they could not control. Children are born into the world without discrimination in their hearts. The way they are brought up into the world is what corrupts them and turns them into racists and oppressors. “Once upon a time they was two girls," I say. "one girl had black skin, one girl had white." Mae Mobley look up at me. She listening. "Little colored girl say to little white girl, 'How come your skin be so pale?'” White girl say, “'I don't know. How come your skin be so black? What you think that mean?'" “But neither one a them little girls knew. So little white girl say, 'Well, let's see. You got hair, I got hair. '"I gives Mae Mobley a little tousle on her head. "Little colored girl say 'I got a nose, you got a nose.'" I gives her little snout a tweak. She got to reach up and do the same to me. "Little white girl say, 'I got toes, you got toes.' And I do the little thing with her toes, but she can't get to mine cause I got my white work shoes on. “So we's the same. Just a different color” (14:198) “Race is not a neutral concept” (6:1) in most of my novels. In a time when everyone believed they were superior, it is easy to imagine someone taking action over 7 their beliefs. People who treat others differently for something as uncontrollable as skin color are comparable to villains like Hitler. Kathryn Stockett, an author from a racial segregated town (2:1), writes about how blacks are treated unequally even though, under law, they are considered equals. “Dirty ain’t a color, disease ain’t the Negro side a town. I want to stop that moment from coming. . . when they start to think that colored folks ain’t as good as whites.” (14:99) When people begin to think they are better than someone else, a number of things can happen. In the United States, segregation and race riots occurred. In Korea, labor camps. In Europe, genocide. Racism has no limit. When a race is singled out as inferior, injustice occurs. There are thousands of cases where people have been mistreated and wronged because the color of their skin or their culture. When you are born, you don’t get to choose what race you want to be; that is chosen for you. In the United States of America’s Declaration of Independence, the forefathers of our country said that “all men are created equal.” Hypocritically, this same nation’s citizens racially discriminated against their own people: blacks, Asians, and even women. Subject to sexism, (racism’s cousin), women had to endure the abuse that men do to make themselves seem more superior to women. Raised with Islamic traditions (15:1), Khaled Hosseini observed arranged marriages and spousal abuse everywhere he went. Reading his novel made me reminisce of the Women’s Suffrage movement that took place in America and the struggles that the women had to go through for basic rights such as the right to vote and own property. This imbalance of rights wasn’t just unique to 8 people of different race or color, but also to anyone who looked different or thought differently. I never understood why people thought blacks and women were different. Both, coloreds and women are people. Nonetheless, someone always thought otherwise; someone who believed “[coloreds] carry different kinds of diseases than we do.” (14:17) I recall the segregated bathrooms for blacks and whites. Every little thing was segregated. Blacks had their own restaurants, bathrooms, churches, and even movie theaters. I can imagine nothing was different it Europe. “[Jews] were no longer allowed to go into restaurants or cafés, to travel on the railways, to attend the synagogue, to go out into the street after six o’clock.” (17:9) All people who were different by the majority’s standards were considered inferior. Early on in all four of my novels, the author creates an aura of unfairness: an aura of inequality. If someone were to be different in thought or appearance, they were treated as such: differently. The minority would be oppressed by the majority and forced to obey their laws. In The Help, “colored folk ain’t allowed in that library,” (14:154) because they are black. Settings even as simple as libraries were segregated. Everything about the minorities’ lives were segregated from the majorities lives. Whites, Aryans, and men all believed that they were better than blacks, Jews, and women, respectively. Those thought to be superiors treated different people as viruses that needed to be controlled and exterminated. In my memories and my novels, there was always a group of people who were victimized. Jews, blacks, and even women were treated as animals and like “swine.” 9 (17:17) In a novel where sexism was a major theme, A Thousand Splendid Suns, women were required to follow rules that limited what they could wear, where they could go, and what they could do. Before the suffrage movement, women had a very limited role in society. A woman’s main purpose in life was to tend to the needs of her husband and bear children. Without a woman’s ability to accomplish these two tasks, she was rendered useless and pathetic. “Oh you’re gonna have some kids. I mean, kids is the only thing worth living for.” (14:40) Brainwashed by society’s expectations, women in both Hosseini and Stockett’s novel are convinced that their sole role in the world was to have children. With this clear division of people, the Jewish people, the African-Americans, the women, and the minorities were maltreated and were subject to injustices. When someone doesn’t like someone, they tend to treat each other as enemies; they fight. Whites fought blacks. Nazis fought Jews. Men fought women. Injustice wasn’t always as severe as violence, but often degraded the victims. Many targets of injustice were forced to submit to their superiors. Women in Afghanistan were forced to obey their parents and participate in arranged marriages. Later, the woman would have to obey her husband and please him by any means necessary. He slid under the blanket beside her. She could feel his hand working at his belt, at the drawstring of her trousers. Her own hands clenched the sheets in fistfuls. He rolled on top of her, wriggled and shifted, and she let out a whimper, Mariam closed her eyes, gritted her teeth. The pain was sudden and astonishing. (14:198) Through the injustices of arranged marriages and the power of men over women, Mariam and Rasheed’s second wife, Laila, were raped numerous times. Injustices to women were 10 a common sight in countries where cultures differed from those of the modern world. But, when it came to injustices to other men, the treatment was either just as bad or worse. Although violence was not a common form of injustice, it did happen. Mostly the injustices exercised in my novels were harmful to the phycology of the characters. The wrongs committed by the whites, Aryans, and men made the victims feel as if they were inferior and had no power to resist their oppressors. The injustices gave the oppressors a sense of control over their victims. “Then the police began suggesting my grandfather should voluntarily bequeath his cherished Volvo to the government. The suggestions became recommendations, the recommendations an order.” (8:34) In North Korea, Kang’s family was forced to relinquish their beloved Volvo to the government. This submission to the government demoralized the family and made them feel as if they had no control or say in their lives. Everywhere you went, you heard slurs. I had a daily routine every morning when I lived in Jackson. Every morning I would go down to the diner and enjoy a cup of coffee and a plate of delicious pancakes, and every time a black person would walk in, the waiter would scream “Get outta here, nigger!” (:135) I never paid any attention to the names they called the coloreds, but deep down inside I felt guilty. I knew there was something wrong with that word. There were slurs for all kinds of people; Jews were called kikes, blacks were called niggers, and Koreans were called chinks. These slurs, along with the other injustices, made the blacks feel lesser than their oppressors. Kang, 11 Mariam, Laila, Aibileen, Minny, and Eliezer could only hope for a way out, an escape from their living nightmare. Just as I had hoped to rid myself of my curse, the protagonists of my novels all had hopes of surviving and enduring. Some characters in my novels even lost hope in surviving. The things they experienced had changed them forever and they lost faith. Despite all my cares, the black champion [the last surviving goldfish] died. . . Seeing his lifeless body floating on the surface of the water filled me with great sadness. . . By this time I was struggling with the problem of my own survival and had little energy left for grieving. With his death, my former world had taken another step. (8:75) This quote from The Aquariums of Pyongyang shows that the loss of something sentimental, his goldfish, could alter his will to survive and persevere. Living in a concentration camp for years can be devastating to a person’s morale, and this devastation is reflected in Kang and Wiesel’s loss of hope and endurance. Their loss was purely due to the fact that were forced to witness and experience, first-hand, sheer inhumanity from the Nazis and the North Koreans. In Night, Eliezer narrated a story about a man who asked, “’Where is God now?,’” (17:62) and another man answered, “’He is hanging here on this gallows.’” (17:62) Not everyone faced the amount of injustice and inhumanity that Kang and Eliezer faced. Their faith and hope were put under extreme pressure, and not many can say they still had hope. The women of my book, Mariam and Laila of A Thousand Splendid Suns and Aibileen and Minnie of The Help, were women who had the strength will to endure their injustice. They preserved and kept fighting until the end. Miriam and Laila believed 12 they had a chance to a better life. “They would make new lives for themselves—peaceful, solitary lives—and there the weight of all that they’d endure would lift from them, and they would be deserving of all the happiness and simple prosperity they would find.” (7:354) Reading these novels reminded me of how I once lost hope and tried taking my own life. The hope that these two women had of surviving their living nightmare was immeasurable when compared to mine. Even Aibileen and Minnie, from The Help, went against the tacit codes of their culture and spoke out against the whites. The women hoped for a time when they could be free of racism, inequality, and injustice. “I realized I actually had a choice in what I could believe.” (14:68) With the friendship and deep connections with children and their help, Skeeter is able to find hope in becoming something other than the average, conforming housewife with a suitable husband and children. Hope was something that went both ways in my conquest back to the twentieth century. Hope could be lost and it could be found, however it was something that played a vital role in each and every character in my novels. In every part of the world I’ve lived in, almost everyone experiences some form of oppression. Oppression is the exercise of authority or power in a burdensome, cruel or unjust manner.2 Whether the oppression is practiced by an abusive husband, a number of white women, Nazi guards, or North Korean communists, the oppression is all the same and has a damaging effect on every single individual. Each book varied on the type of 2 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oppression 13 oppression that was exercised. Some were oppressed verbally, some physically, and some mentally. Walking down the street and finding a pro-Nazi poster was a common sight in 1940s Europe. Everywhere I walked there were posters of Uncle Sam, Hitler, and Churchill: each poster trying to oppress us mentally and convince us that their cause was more right than the other. In concentration camps like the one Elie and Kang depicted, the Nazis and North Koreans, respectively, used mental oppression to try and diminish the morale of the prisoners. “The punishment for attempted escape is execution. No exceptions.” The guards make the whole village come out to watch it. . . So given all that, I have a hard time seeing the mountains as very beautiful. We were silent, but the look on our faces, must have communicated our horror. (8:57) Elie and Kang’s oppressors would use fear and threats to weaken their spirits. Oppression was something that all people faced. It was faced by women and men alike. Oppression was even exercised by women! In Stockett’s novel, The Help, the black maids are oppressed by their white superiors. “It was so obvious what she wanted. Hilly cleared her throat and finally Aibileen lowered her head. ‘Thank you, ma’am.’ She whispered.” Fearing the loss of their jobs, Aibileen and Minnie did what their white, female oppressors told them to do. Not only would the antagonists of my novels use verbal oppression, but also physical oppression. Machiavelli once asked, “Is it better to be loved than feared or feared than loved?” Obviously in some of my novels violence and fear were used to have a sense of power over someone. In A Thousand Splendid Suns, Rasheed uses violence to keep 14 Mariam from acting out and embarrassing him. He punishes her by forcing her to chew rocks. “Mariam chewed. Something in the back of her mouth cracked. ‘Good,’ Rasheed said.” (8:104) During a time of war, physical strength is used to oppress others. Strength shows that no one is above you, and that is exactly what the Nazis and the North Koreans showed to the prisoners in the camps and gulags. These oppressors showed their strength by committing acts of terror and pure inhumanity. Everywhere I have been, there has been violence; but, only in few places have I witnessed inhumanity. The fact that people can commit acts of such horror and inhumanity is unbelievable. “’Humanity? Humanity is not concerned with us. Today anything is allowed. Anything is possible, even these crematories.’” (17:30) Inhumanity can be seen throughout the world, it is seen in Europe, the United States, the Middle East, and even in the Far East. However, not all inhumanity is in the form of genocide; some forms are depicted through local, domestic violence. In each of my novels, inhumanity is practiced most commonly through acts of extreme violence. Two of my novels, The Help and A Thousand Splendid Suns, represented inhumanity on a more local scale, while my other two novels contained motifs of inhumanity on a much more global scale: so global in fact that it was considered genocide. In A Thousand Splendid Suns, Laila and Mariam are beaten and raped over and over by their abusive husband, Rasheed; whereas, in my other novels “babies were thrown into the air and machine gunners [would use] them as targets.” (17:4) 15 I remember reading the daily newspaper and splashed on the front page would be a black and white image of hundreds, maybe thousands, of bodies piled on top of one another, and the headlines would read “GENOCIDE.” How can someone murder millions of innocent people due to something they had no say in: their race. The oppressors didn’t hold back when they wanted to show their power. “Without passion, without haste, they slaughtered” (17:4) hundreds of people day in and day out. The murders would not hesitate when they had a chance to express their power. A Myong-Chul, a former camp guard who escaped to the South, has talked about the barbarous punishment he saw inflicted on women found guilty of sexual relations. There was a pregnant woman who was bound to a tree and flogged, another who had her breasts cut off, a third who died after being raped with a spade handle.” (8:146) Acts like the one quoted above are acts that have been committed over and over, without hesitation. These horrors not only leave scars on flesh, but they also scar on the soul. Witnessing millions of dead bodies through the newspaper is nightmare enough. I can only imagine the torment that victims of the Holocaust or North Korean gulags had to suffer. Being a part of something as inhumane as genocide, constant spousal abuse, or starvation, can affect a person’s outlook on the world. The victims remained the same physically; however, inside, “a dark flame had entered into [their] soul[s] and devoured [them].” Over time, the constant struggle to survive changed people. People would fight one another over a few breadcrumbs or an extra spoonful of soup. Sons would betray their fathers. These atrocities turned civilized men into savages. Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp which has turned my life into one long night. Never shall I forget that smoke. Never shall I forget 16 the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky. Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever. Never shall I forget that nocturnal silence which deprived me of the desire to live. Never shall I forget those moments which turned my dreams to dust. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never. (17:32) I can’t imagine a worse century. I’ve stopped counting birthdays, for I don’t want to know how long my curse has been around. But if I were to guess how old I am, I would assume almost 300 years old. I’ve been through it all. I’ve seen nations rise. I’ve seen them fall. I’ve seen peace, and I’ve seen war. I’ve seen many die. I’ve lived too long to be able to bear any more death and injustice on the scale of any of the genocides and injustices in my novels. Humanity needs to change the way it has been acting. We, as people, cannot fight among ourselves. We cannot decide who is better than someone else. The world needs more organizations like the United Nations and the World Peace Council. I’ve lived my share of years and I’ve kept my lips sealed for too long. The world needs peace. I, and many others, believe that the world needs to end the fighting. End the bloodshed. I will not stand for a society that will discriminate people based on someone’s skin color or ethnicity. Bob Marley, prominent musician, once said that “the color of a man's skin is of no more significance than the color of his eyes.” Until that statement has become true, I cannot live among oppressors and murderers. “For the dead and the living, we must bear witness.” - Elie Wiesel 17 Epilogue Tired of life, tired of school, and tired of the world, Dorian chose to escape society and to live on his own. With the money he’s saved over the numerous centuries, Dorian fled society and lived a life of peace. He ran away to Switzerland, a country of peace and tranquility, where he could avoid inequality, oppression, racism, injustice, and inhumanity. 18 About the Author Justin Douglas Outten, born in a cotton field to Jameson Outten and Victoria Davidson, grew up in a small town in Ohio with his four sisters. He dropped out of school at aged sixteen and escaped with his girlfriend, Katrina, to Florida to pursue his dream in surfing. Four years after arriving, he got attack by a great white shark and lost his right leg. He became a vegetable and had to stay in bed all day, so he decided to pass time by writing about the times he had surfed. In 1968, he published his first book, and continued writing until he died in 1998. 19 Bibliography 1. "The Aquariums of Pyongyang:." Google Books. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://books.google.com/books/about/The_Aquariums_of_Pyongyang.html?id=8XzbKfI2GUC>. 2. "Biography." Kathryn Stockett, Author of The Help. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://kathrynstockett.com/biography/>. 3. Bloom, Harold. Elie Wiesel's Night. Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2001. Print. 4. Glionna, John M. "North Korea Gulag Spurs a Mission." Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times, 07 Apr. 2010. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://articles.latimes.com/2010/apr/07/world/lafg-north-korea-gulags8-2010apr08>. 5. "Handley | Review of 'Hell on Earth: Life in Kim Il-Sung's Gulag'" Handley | Review of 'Hell on Earth: Life in Kim Il-Sung's Gulag' Web. 26 May 2012. <http://www.unc.edu/depts/diplomat/archives_roll/2002_1012/book_handley/book_handley.html>. 6. "The Help." Shmoop. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://www.shmoop.com/the-help/>. 7. Hosseini, Khaled. A Thousand Splendid Suns. New York: Riverhead, 2007. Print. 8. Kang, Chʻŏr-hwan, and Pierre Rigoulot. The Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in a North Korean Gulag. New York: Basic, 2001. Print. 9. "Khaled Hosseini Biography." -- Academy of Achievement. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/hos0bio-1>. 10. "Night." Shmoop. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://www.shmoop.com/night/>. 11. "Night." SparkNotes. SparkNotes. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://www.sparknotes.com/lit/night/>. 20 12. "ReadingGroupGuides.com - The Help by Kathryn Stockett." ReadingGroupGuides.com The Help by Kathryn Stockett. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://www.readinggroupguides.com/guides_h/the_help1.asp>. 13. "Review of Kang Chol-Hwan's The Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in the North Korean Gulag - BrothersJudd.com." Review of Kang Chol-Hwan's The Aquariums of Pyongyang: Ten Years in the North Korean Gulag - BrothersJudd.com. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://www.brothersjudd.com/index.cfm/fuseaction/reviews.detail/book_id/1438/>. 14. Stockett, Kathryn. The Help. New York: Amy Einhorn, 2009. Print. 15. "A Thousand Splendid Suns." By Khaled Hosseini: Study Guide / Chapter Summary / Book Notes / Analysis / Synopsis / Download. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://thebestnotes.com/booknotes/Thousand_Splendid_Suns_Hosseini/Thousand_Splendi d_Suns_Study_Guide01.html>. 16. "A Thousand Splendid Suns Study Guide & Essays." A Thousand Splendid Suns Study Guide & Literature Essays. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://www.gradesaver.com/a-thousandsplendid-suns/>. 17. Wiesel, Elie, Josh Perry, and Jon Natchez. Night: Elie Wiesel. New York: Spark Pub., 2002. Print. 18. Windrem, Robert. "Death, Terror in N. Korea Gulag." Msnbc.com. Msnbc Digital Network. Web. 26 May 2012. <http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/3071466/ns/us_newsonly_on_msnbc_com/t/death-terror-n-korea-gulag/>. 21