Université Libanaise Rectorat Educational Psychology Course

advertisement

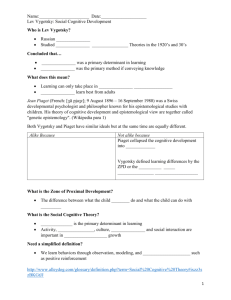

Université Libanaise Rectorat Educational Psychology Course Instructor: Dr Rita Zgheib Rita.zgheib@gmail.com 1 COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT -1 1.1 3 HOURS: NOVEMBER 25, 2014 COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENTAL THEORIES Learning is more powerful if learners actively construct their own understandings. Learning experiences are far more effective if they take into account the cognitive development levels of learners. Students’ knowledge construction is assisted by the nature of their interactions with people and objects in their environment. Cognitive development “involves changes in reasoning and thinking, language acquisition, and the ways individuals gain store and remember or recall knowledge of their environment.” – Seifert and Hoffmung, 1994, p. 6. 1.2 CONSTRUCTIVISM - PIAGET Jean Piaget (1896 –1980) was a Swiss developmental psychologist and philosopher known for his epistemological studies with children. His theory of cognitive development and epistemological view are together called "genetic epistemology". Genetic epistemology is a study of the origins (genesis) of knowledge (epistemology). The discipline was established by Jean Piaget. The goal of genetic epistemology is to link the validity of knowledge to the model of its construction. It shows that how the knowledge was gained affects how valid it is. Piaget placed great importance on the education of children. As the Director of the International Bureau of Education, he declared in 1934 that "only education is capable of saving our societies from possible collapse, whether violent, or gradual. Jean Piaget was "the great pioneer of the constructivist theory of knowing”. However, his ideas did not become widely popularized until the 1960s. Piaget was born in Neuchâtel, in the Francophone region of Switzerland. Piaget was a precocious child who developed an interest in biology and the natural world. His early interest in zoology earned him a reputation among those in the field after he had published several articles on mollusks by the age of 15. He was educated at the University of Neuchâtel, and studied briefly at the University of Zürich. Piaget moved from Switzerland to Paris, France after his graduation and he taught at the GrangeAux-Belles Street School for Boys. The school was run by Alfred Binet, the developer of the Binet intelligence test, and Piaget assisted in the marking of Binet's intelligence tests. It was while he was helping to mark some of these tests that Piaget noticed that young children consistently gave wrong answers to certain questions. Piaget did not focus so much on the fact of the children's Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 1 of 15 answers being wrong, but that young children consistently made types of mistakes that older children and adults did not. This led him to the theory that young children's cognitive processes are inherently different from those of adults. Ultimately, he was to propose a global theory of cognitive developmental stages in which individuals exhibit certain common patterns of cognition in each period of development. In 1921, Piaget returned to Switzerland as director of the Rousseau Institute in Geneva. In 1923, he married and had three children, whom Piaget studied from infancy. In 1964, Piaget was invited to serve as chief consultant at two conferences at Cornell University (March 11–13) and University of California, Berkeley (March 16–18). The conferences addressed the relationship of cognitive studies and curriculum development and strived to conceive implications of recent investigations of children's cognitive development for curricula. In 1979 he was awarded the Balzan Prize for Social and Political Sciences. Piagetian theory consists of two main parts: A. His ideas about the purpose and nature of intelligence. B. A stage theory perspective on human cognitive development. A. Piagetian View of Intelligence: . Intelligence: A set of cognitive capabilities that allows people to adjust to the demands of the environment. These capabilities are: 1. Knowledge Structures: The basic structure is the scheme or schema – an organized pattern of thought or action used by people to understand and interact with their world. People tend to organize knowledge about their experiences into categories. All cats in the neighborhood meow. Scheme for understanding cats: All cats meow. CASES: Mrs. Rayburn, a junior high science teacher, is amazed how resilient her students' belief systems are. She shows them a science demonstration that contradicts their beliefs, and the students find a way to make the demonstration fit with their beliefs. "I guess that's one reason why it is hard to change students' misconceptions about science." Mrs. Pantera's sixth grade science students often have developed some misunderstandings of physical science concepts such as heat and gravity. "I often need to assess students' understanding of these concepts before I introduce them. I can then try to create experiences that allow them to confront and hopefully change their particular misunderstandings." Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 2 of 15 . These are examples of cognitive functions. But what are cognitive functions? 2. Cognitive Functions: Organization: The general tendency of biological organisms to combine structures into more complicated structures or systems. Adaptation: The process used to develop and refine schemes to adjust to our environments.It occurs through two complementary subprocesses: •Assimilation: Interpreting environmental events in terms of existing schemes. Infant calls ALL men "Daddy!" •Accomodation: When evironmental experiences cause a person to change the nature of a scheme. Not all men are Daddy. . Relate each of the cases above to a subcategory of adaptation. . Self-Regulation: From a Piagetian perspective, people are motivated to make sense of the world so they can adapt to its demands. To accomplish this, people must self-regulate and maintain a sense of balance among the many factors that influence their ability to understand and adapt to their environments – cognitive balance. Equilibrating means assessing current understanding in terms of how well it explains experiences and maintaining an appropriate balance between assimilation and accommodation in making sense of these experiences. CORNERSTONE IDEAS for the constructivist approach. B. Piagetian Stage Theory: . Assumptions: Each stage is characterized by the development of cognitive structures or capabilities that are qualitatively different from those of earlier stages. The sequence of stages is the same for all children; but the timing can change. Development is cumulative. Children may demonstrate capabilities from two stages simultaneously – horizontal décalage. In general, development occurs through a series of four stages: Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 3 of 15 Formal Operations Stages: Concrete Operations Preoperational Sensorimotor 0-2 1. 2-6 or 7-10 or 11 11-13 Years Sensorimotor: Infants think and develop schemes through their motor responses to stimuli in their environment. By the end of this stage infants should have developed: - Intentionality: Actions are no longer mere neonatal reflexes. - Object Permanence: Infants demonstrate permanence by continuing to search for objects that are hidden or out of sight (18-24 months old). 2. Preoperational: Symbolic Thought: the ability to think symbolically - Semiotic function. a. Deferred imitation: The ability to imitate a model that is no longer there. b. Symbolic play: Pretend play; make believe. An excellent example of assimilation. Characteristics of the Preoperational Stage: - Irreversibility: Their operations cannot be reversed. - Egocentrism: Tendency to judge things from their point of view. - Centration: Limit of perspective to one aspect of a complicated stimulus. 3. Concrete Operations: . They understand the nature of physical realities. a. Conservation: change in appearance does not mean a change in quantity. Identity If nothing is added or taken away nothing changes. Negation For an action, there is another that undoes its effect . Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 4 of 15 Compensation Changes in one aspect explains the observed change in another. b. Seriation and Classification: Series: 1, 2, 3, 4. Categories: positive digits Formal Operations: a. Hypothetico-Deductive Reasoning: The ability to reason from hypotheses. Become capable of forming theories and hypotheses. b. Propositional Logic: The ability to determine the truth or fallacy of propositions that may or may not have a basis in experience. c. Ability to Consider What-Ifs: The ability to go beyond the content of the logic they are evaluating. Current Status to the Piagetian Theory: Piagetians tend to underestimate the capabilities of infants and young children. Children’s performance seems to be influenced by a number of factors other than cognitive development. As many as 40-60% of young adults and adolescents do not achieve formal operational thought. Development is so gradual that two people within the same stage may be very different in terms of their cognitive development. Movement from one stage to the other occurs gradually. . THE COMPETENCE/PERFORMANCE RELATIONSHIP. 1.3 VYGOTSKY’S SOCIO-HISTORICAL THEORY Lev Semyonovich Vygotsky: (1896 – 1934) was a Soviet psychologist, the founder of a theory of human cultural and bio-social development commonly referred to as cultural-historical psychology, and leader of the Vygotsky Circle. Vygotsky's main work was in developmental psychology, and he proposed a theory of the development of higher cognitive functions in children that saw reasoning as emerging through practical activity in a social environment. Vygotsky also posited a concept of the Zone of Proximal Development, often understood to refer to the way in which the acquisition of new knowledge is dependent on previous learning, as well as the availability of instruction. During his lifetime Vygotsky's theories were controversial within the Soviet Union. In the 1930s Vygotsky's ideas were introduced in the West where they remained virtually unknown until the 1970s when they became a central component of the development of new paradigms in developmental and educational psychology. . The major emphasis of Vygotsky’s theory is the importance of understanding cognitive development in terms of the social and cultural contexts in which it occurs. Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 5 of 15 A. The Role of Cultural Tools in Cognitive Development . Each environment provides cultural tools to support or mediate students’ activities: Technical Tools: Cultural tools that are used to act on objects A hammer and a nail Psychological Tools: Cultural tools that guide or mediate thoughts and behaviors Language; mnemonics B. Development of Higher Order Mental Functions . A function is a mental process such as attention, memory, perception, and thinking. These functions appear first in their elementary form which develop naturally in all living creatures and are not voluntary. . Higher mental functions are unique to humans, are under the control of the person, social in origin, and are assisted by psychological tools. C. General Genetic Law of Cultural Development . Any higher form of mental functions exists first on the social level. Internalization is the process by which an individual acquires the social higher order mental functions. – Egocentric speech which gradually becomes inner speech. . Zone of proximal development DISTANCE What a learner can accomplish while working with a more skilled adult or a peer What a learner can accomplish independently in a domain D. The Historical Process of Cultural Development . Vygotsky believed that theory in human development must account for the changes that occur at four historical levels: Phylogeny The development of the species The history of humans since becoming a species Ontogeny The history of individual children The history of development of psychological processes during an experimental task . This is of vital importance to the teacher in the classroom: - First: Ontogeny is important: Two students fail the course. Each for a different reason. Thus, two different remedies. - Second: Individual development in terms of the individual’s cultural or social group. Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 6 of 15 Educational Implications of the Vygotskian Theory A. The Zone of Proximal Development and Strategy and Skill Learning 1. Tutoring within the zone of proximal development: In a tutorial approach, learners interact with more skilled peers or adults to perform a task that those learners cannot perform independently. This guidance is referred to as scaffolding. Scaffolding is a threestep process: Adult or skilled learner assumes most of the responsibility for completing the task. Adult or skilled learner share the responsibility for completing the task with the student gradually relinquishing control to the learner. Learner takes full responsibility for completing the task. 2. Collaborative problem solving within the zone of proximal development: In this case, the idea of scaffolding by a more skilled learner is replaced by the ideas of two learners collaborating together to accomplish a goal. B. The Zone of Proximal Development and Assessment To assess learning potential more accurately, Vygotskians suggested that standardized ability tests should be supplemented with measures of a learner’s zone of proximal development. In this case, evaluators would scaffold learners as they attempted problems that were slightly above the assessed independence level. 1.4 A. GESTALT – WERTHEIMER, KOFKA, AND KOHLER Gestalt Psychology Gestalt psychology, founded by Max Wertheimer, was to some extent a rebellion against molecularism. In fact, the word Gestalt means a unified or meaningful whole, which was to be the focus of psychological study instead. It had its roots in a number of older philosophers and psychologists: Ernst Mach (1838-1916) introduced the concepts of space forms and time forms. We see a square as a square, whether it is large or small, red or blue, in outline or technicolor... This is space form. Likewise, we hear a melody as recognizable, even if we alter the key in such a way that none of the notes are the same. Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 7 of 15 Christian von Ehrenfels (1859-1932), is the actual originator of the term Gestalt as the Gestalt psychologists were to use it. In 1890, in fact, he wrote a book called On Gestalt Qualities. One of his students was none other than Max Wertheimer. Oswald Külpe (1862-1915) is best known for the idea of imageless thoughts. He showed that some mental activities, such as judgments and doubts, could occur without images. Max Wertheimer (1880 – 1943). Max studied law for more than two years, but decided he preferred philosophy. He left to study in Berlin, where he took classes from Stumpf, then got his doctoral degree (summa cum laude) from Külpe and the University of Würzburg in 1904. In 1910, he went to the University of Frankfurt’s Psychological Institute. While on vacation that same year, he became interested in the perceptions he experienced on a train. While stopped at the station, he bought a toy stroboscope -- a spinning drum with slots to look through and pictures on the inside, sort of a primitive movie machine or sophisticated flip book. His first subjects were two younger assistants, Wolfgang Köhler and Kurt Koffka. They would become his lifelong partners. He published his seminal paper in 1912: "Experimental Studies of the Perception of Movement." In 1933, he moved to the United States to escape the troubles in Germany. While there, he wrote his best known book, Productive Thinking, which was published posthumously by his son, Michael Wertheimer, a successful psychologist in his own right. Wolfgang Köhler (1887 – 1967) received his PhD in 1908 from the University of Berlin. He then became an assistant at the Psychological Institute in Frankfurt, where he met and worked with Max Wertheimer. In 1922, he became the chair and director of the psychology lab at the University of Berlin, where he stayed until 1935. During that time, in 1929, he wrote Gestalt Psychology. In 1935, he moved to the U.S. Kurt Koffka (1886 – 1941 received his PhD from the University of Berlin in 1909, and, just like Köhler, became an assistant at Frankfurt. In 1911, he moved to the University of Giessen, where he taught till 1927. While there, he wrote Growth of the Mind: An Introduction to Child Psychology (1921). In 1922, he wrote an article for Psychological Bulletin which introduced the Gestalt program to readers in the U.S. In 1927, he left for the U.S. to teach at Smith College. He published Principles of Gestalt Psychology in 1935. B. The Theory Gestalt psychology is based on the observation that we often experience things that are not a part of our simple sensations. The original observation was Wertheimer’s, when he noted that we perceive motion where there is nothing more than a rapid sequence of individual sensory events. This is what he saw in the toy stroboscope he bought at the Frankfurt train station, and what he saw in his laboratory when he experimented with lights flashing in rapid succession (like the Christmas lights that appear to course around the tree, or the fancy neon signs in Las Vegas that seem to move). The effect is called apparent motion, and it is actually the basic principle of motion pictures. If we see what is not there, what is it that we are seeing? You could call it an illusion, but it’s not a hallucination. Wertheimer explained that you are seeing an effect of the whole event, not Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 8 of 15 contained in the sum of the parts. We see a coursing string of lights, even though only one light lights at a time, because the whole event contains relationships among the individual lights that we experience as well. Furthermore, say the Gestalt psychologists, we are built to experience the structured whole as well as the individual sensations. And not only do we have the ability to do so, we have a strong tendency to do so. We even add structure to events which do not have gestalt structural qualities. C. The Gestalt Laws In perception, there are many organizing principles called gestalt laws. 1. The most general version is called the law of pragnanz. Pragnanz is German for pregnant, but in the sense of pregnant with meaning, rather than pregnant with child. This law says that we are innately driven to experience things in as good a gestalt as possible. “Good” can mean many things here, such a regular, orderly, simplicity, symmetry, and so on, which then refer to specific gestalt laws. For example, a set of dots outlining the shape of a star is likely to be perceived as a star, not as a set of dots. We tend to complete the figure, make it the way it “should” be, finish it. Like we somehow manage to see this as a "B"... 2. The law of closure says that, if something is missing in an otherwise complete figure, we will tend to add it. A triangle, for example, with a small part of its edge missing, will still be seen as a triangle. We will “close” the gap. 3. The law of similarity says that we will tend to group similar items together, to see them as forming a gestalt, within a larger form. Here is a simple typographic example: OXXXXXXXXXX XOXXXXXXXXX XXOXXXXXXXX XXXOXXXXXXX XXXXOXXXXXX XXXXXOXXXXX XXXXXXOXXXX XXXXXXXOXXX XXXXXXXXOXX XXXXXXXXXOX XXXXXXXXXXO It is just natural for us to see the o’s as a line within a field of x’s. 4. Another law is the law of proximity. Things that are close together as seen as belonging together. For example... Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 9 of 15 ************** ************** ************** You are much more likely to see three lines of close-together *’s than 14 vertical collections of 3 *’s each. 5. [ Next, there’s the law of symmetry. Take a look at this example: ][ ][ ] Despite the pressure of proximity to group the brackets nearest each other together, symmetry overwhelms our perception and makes us see them as pairs of symmetrical brackets. 6. Another law is the law of continuity. When we can see a line, for example, as continuing through another line, rather than stopping and starting, we will do so, as in this example, which we see as composed of two lines, not as a combination of two angles...: 7. Figure-ground is another Gestalt psychology principle. It was first introduced by the Danish phenomenologist Edgar Rubin (1886-1951). The classic example is this one... Basically, we seem to have an innate tendency to perceive one aspect of an event as the figure or fore-ground and the other as the ground or back-ground. There is only one image here, and yet, by changing nothing but our attitude, we can see two different things. It doesn’t even seem to be possible to see them both at the same time! But the gestalt principles are by no means restricted to perception -- that’s just where they were first noticed. Take, for example, memory. That too seems to work by these laws. If you see an irregular saw-tooth figure, it is likely that your memory will straighten it out for you a bit. Or, if you experience something that doesn’t quite make sense to you, you will tend to remember it as having meaning that may not have been there. A good example is dreams: Watch yourself the next time you tell someone a dream and see if you don’t notice yourself modifying the dream a little to force it to make sense! Learning was something the Gestalt psychologists were particularly interested in. One thing they noticed right away is that we often learn, not the literal things in front of us, but the relations between them. For example, chickens can be made to peck at the lighter of two gray Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 10 of 15 swatches. When they are then presented with another two swatches, one of which is the lighter of the two preceding swatches, and the other a swatch that is even lighter, they will peck not at the one they pecked at before, but at the lighter one! Even something as stupid as a chicken “understands” the idea of relative lightness and darkness. Gestalt theory is well known for its concept of insight learning. People tend to misunderstand what is being suggested here: They are not so much talking about flashes of intuition, but rather solving a problem by means of the recognition of a gestalt or organizing principle. The most famous example of insight learning involved a chimp named Sultan. He was presented with many different practical problems (most involving getting a hard-to-reach banana). When, for example, he had been allowed to play with sticks that could be put together like a fishing pole, he appeared to consider in a very human fashion the situation of the out-of-reach banana thoughtfully -- and then rather suddenly jump up, assemble the poles, and reach the banana. A similar example involved a five year old girl, presented with a geometry problem way over her head: How do you figure the area of a parallelogram? She considered, then excitedly asked for a pair of scissors. She cut off a triangle from one end, and moved it around to the other side, turning the parallelogram into a simple rectangle. Wertheimer called this productive thinking. The idea behind both of these examples, and much of the gestalt explanation of things, is that the world of our experiencing is meaningfully organized, to one degree or another. When we learn or solve problems, we are essentially recognizing meaning that is there, in the experience, for the “dis-covering.” Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 11 of 15 Isomorphism suggests that there is some clear similarity in the gestalt patterning of stimuli and of the activity in the brain while we are perceiving the stimuli. There is a “map” of the experience with the same structural order as the experience itself, albeit “constructed” of very different materials! We are still waiting to see what an experience “looks” like in an experiencing brain. 1.5 BRUNER’S COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENTAL THEORY Jerome Seymour Bruner: (October 1, 1915) is a psychologist who has made significant contributions to human cognitive psychology and cognitive learning theory in educational psychology, as well as to history and to the general philosophy of education. Bruner is currently a senior research fellow at the New York University School of Law. He received a B.A. in 1937 from Duke University and a Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1941. Jerome Bruner received a bachelor's degree in psychology, in 1937 from Duke University. He went on to earn a master's degree in psychology in 1939 and then a doctorate in psychology in 1941 from Harvard University. Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 12 of 15 In 1939, Bruner published his first psychological article studying the effect of thymus extract on the sexual behavior of the female rat. During World War II, Bruner served on the Psychological Warfare Division of the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditory Force Europe committee under Eisenhower, researching social psychological phenomena. In 1945, Bruner returned to Harvard as a psychology professor and was heavily involved in research relating to cognitive psychology and educational psychology. In 1970, Bruner left Harvard to teach at the University of Oxford in England. He returned to the United States in 1980 to continue his research in developmental psychology. In 1991, Bruner joined the faculty at New York University, where he still teaches students today. As an adjunct professor at NYU School of Law, he studies how psychology affects legal practice. Throughout his career, Bruner has been awarded honorary doctorates from Yale and Columbia, as well as colleges and universities in such locations as Sorbonne, Berlin, and Rome, and is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. A. Knowledge Representation According to Bruner, an important factor in the development of an intelligent mind is the ability to represent knowledge. Knowledge representations allow learners to store rules or generalizations that can organize and explain recurrent themes in their experience. Bruner cites three systems of representations which develop in sequence. By the time people reach adolescence, they typically have all three representation systems. Representation 1. Enactive 2. Iconic 3. Symbolic Description Example Remarks Representation through The series of actions for Children may know how to motor responses tying a knot do things that they cannot explain verbally The use of mental images to Reporting knowledge of Verbal messages are better represent knowledge circles by a mental picture of understood when circles represented in the form of pictures The use of arbitrary symbol A student represents a rule Very important in the systems such as language or such as” I need to invert and development of logic mathematical notation multiply when I divide fractions” B. Culture and Cognitive Development Similar to Vygotsky’s cultural tools, Bruner has amplifiers. He believed that cultural systems assist cognitive development by helping learners acquire the amplification systems of the culture. Amplifiers of action Hammers & shovels Amplifiers of senses Microscopes & pictures Amplifiers of thought Logic systems & language One particular form of an instructional interaction that interested Bruner is the interaction between adults and children in problem-solving situations. Adults guide or support learners as they solve problems together – scaffolding. Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 13 of 15 C. Bruner and Classroom Instruction Discovery Learning: Knowledge students discover for themselves is the most unique personal knowledge they have. – OWNERSHIP. “Discovery, like surprise, favors the well-prepared mind.” Bruner also supported scaffolded discovery learning. D. Curriculum Design: 1. The Psychology of a Subject Matter: This includes: a. The key organizing principles or ideas of a discipline. b. The characteristic way in which practitioners of that discipline solve problems. The importance of organizing a curriculum around the psychology of the subject matter is that it tends to replace breadth of coverage with depth of coverage, an idea referred to as less is more. 2. Spiral Curriculum: Periodically revisiting key organizing ideas in a discipline throughout a curriculum. Each time an idea is revisited, it is done at a higher level of complexity. Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 14 of 15 1.6 CONSTRUCTIVISM Dr. Rita Zgheib - Page 15 of 15