THE FINNISH POLITICAL SYSTEM (5 ECTS)

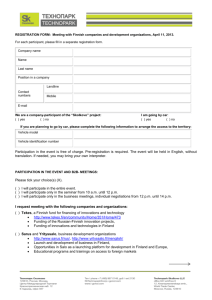

advertisement