Document 9991278

advertisement

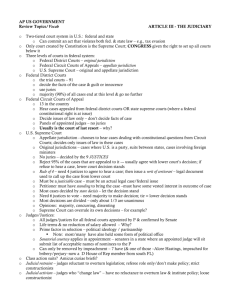

1 CHAPTER 12 The Supreme Court and American Judiciary The National Court System 2 There are three criteria that distinguish the Supreme Court and other courts from the rest of the national government: The judiciary operates only in the context of cases. Cases develop in a strictly prescribed fashion. Judges rely heavily on reason in justifying what they do. Cases: Raw Material for the Judiciary A case refers to a dispute handled by a court. Criminal cases involve a crime or public wrong against society. Civil cases are actions involving a private wrong or dispute. The National Court System (continued) 3 Fifty-one Judicial Systems The national court system consists of state courts and federal courts, each of which hears different kinds of cases. Jurisdiction refers to the authority a court has to entertain a certain case. This is dependent on who is involved and the subject matter the case entails. State and federal courts are both bound by the Constitution, and each may have cases appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. The United States Court System 4 Almost all cases the Supreme Court decides each year are the part of its appellate jurisdiction. These cases begin in the state and federal courts. State and Local Courts 5 These courts handle the great bulk of legal business. State judicial systems are usually divided into four tiers. Courts of limited jurisdiction hear minor cases in villages, towns, and cities; a judge alone usually decides minor cases. Courts of general jurisdiction, usually located in each county, hear appeals and serious criminal offenses and civil suits. Intermediate appellate courts accept appeals from courts of general jurisdiction. Courts of last resort (usually state supreme courts) hear final appeals. Most state judges are elected. In some instances, the Missouri Plan allows the governor to appoint judges from a list of nominees. Judges may be subject to periodic retention votes. Typical Organization of State Courts 6 Each state has its own system of state courts. No system is exactly like another, but all are organized in a hierarchy similar to that pictured here. All states have courts of limited jurisdiction, courts of general jurisdiction, and a court of last resort. In Texas and Oklahoma, there are two separate courts of last resort—one for criminal appeals and one for all other types of cases. Most, but not all, states have at least one intermediate appellate court. In the 12 states that have no intermediate court, cases move on to appeal from courts of general jurisdiction to the court of last resort. United States District Courts, and Courts of Appeal 7 United States District Courts The Judiciary Act of 1789 organized a national court system. Almost all federal cases begin in the 94 United States district courts. United States Courts of Appeals There are 13 United States courts of appeals,12 of which have a regional jurisdiction or circuit. Appeals judges sit in panels of three and hear cases on appeal from district courts or the tax court and review rulings from federal agencies. The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit hears appeals in patent cases as well as all appeals from the Claims court, Court of International Trade, and Court of Veterans Appeals. Geographic Boundaries of U.S. Courts of Appeals and U.S. District Courts 8 The map shows how the 94 U.S. district courts and 13 U.S. courts of appeals exist within the court systems of the 50 states and the District of Columbia Special Courts 9 Tribunals created by Congress to hear specific kinds of cases include the following: Court of Federal Claims Court of International Trade Tax Court Court of Veterans Appeals Court of Military Appeals Except for the Court of International Trade, all are legislative courts created by Congress to assist with implementation of statutes. Judges in constitutional courts are appointed by the president and serve during good behavior, while Congress specifies the appointment and terms of judges in legislative courts. The Supreme Court of the United States 10 The Supreme Court has appellate jurisdiction: the authority to review decisions made by federal courts, as well as decisions of the highest state courts that raise federal questions. Almost all cases reach the Supreme Court on a writ of certiorari, and at least four justices must agree to accept a case (rule of four). The Supreme Court has original jurisdiction in four kinds of disputes: Cases between one of the states and the U.S. government Cases between two or more states The Supreme Court of the United States (continued) 11 Cases involving foreign ambassadors, ministers, or consuls Cases begun by a state against a citizen of another state or country. (The Eleventh Amendment requires suits against a state by a citizen of another state or country to go the state court) Today only cases between states qualify exclusively as original cases for the Supreme Court. The chief justice of the United States, whose vote is equal to that of any other associate justice, heads the Court. Federal Judicial Selection 12 All federal judges are appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Federal judges have no constitutional qualifications. Senatorial courtesy allows home-state senators to strongly influence the fate of presidential nominees. The American Bar Association rates the qualification of nominees. Federal Judicial Selection (continued) 13 A president’s selection of a Supreme Court justice is based upon the following: Professional qualifications Senate acceptability Ideological fit Personal friendship Other background factors Supreme Court justices have not been generally representative of American society. Senate confirmation is not automatic, and several recent nominees have been rejected. What Courts Do 14 Constitutional Interpretation Judicial review allows a court to set aside laws made by elected officials if judges believe the law violates the Constitution. Political groups that have failed to settle their differences in the executive or legislative branches often resort to arguing opposing interpretations of the Constitution in court. Statutory Interpretation Often courts are required to interpret laws that may be vague. Judges may need to discover legislative intent when unanticipated ambiguities arise. What Courts Do (continued) 15 Fact Determination Judges attempt to discern the truth from competing testimony and evidence. Fact determination is most visible in a trial court. Clarification of the Boundaries of Political Authority Courts attempt to resolve conflicts between the branches of government over the exercise of power. In 1952, the Supreme Court declared President Truman had exceeded his powers by seizing the steel mills as part of the war effort. What Courts Do (continued) 16 Education and Value Application Judges apply values and teach by making decisions. Through opinion leaders like journalists and scholars, court decisions help shape public attitudes. Legitimation In most cases, courts provide legitimacy to the law by upholding challenged laws or policies. The Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the civil rights laws of the 1960s virtually ended the controversy. The Supreme Court at Work 17 Petition for Review Lawyers file briefs with the Court’s clerk, requesting that the Court consider the issues raised in the case. Cases are decided in several different ways: With full opinion Summarily Without opinion They are denied review. The Supreme Court at Work (continued) 18 Chances for review are enhanced if one or more or more of the following factors exist: The United States is a party to the case and requests Supreme Court review. Different courts of appeals have decided differently on the issue. The case involves an issue the justices are eager to resolve. A lower court has made a decision at odds with the established Supreme Court interpretations. The Court’s workload permits acceptance of another case. The case represents a critical national issue. Caseload in the U.S. Supreme Court, 1950-2008 19 Figure 12.4 shows the number of cases appealed to the Supreme Court in each of seven years and the number of cases decided with full opinion. The justices decide other cases summarily each term. The number of summary decisions each term sometimes equals the number of cases decided with full opinion. The volume of cases has grown almost eightfold since 1950, while the number of cases decided has varied only modestly. Indeed, since 1988 when 171 decisions were issued, the Court has been deciding fewer cases, a trend aided by the virtual elimination of the Court’s obligatory appellate jurisdiction in 1988. Almost all of each year’s cases come from the lower federal courts and the state supreme courts. Only a handful, at most, of original cases appears each term. A minimum of four justices must agree to hear a case. The Supreme Court at Work 20 Briefs on the Merits A second round of briefs focus on persuading the justices as to what decision they should make. Amici curiae briefs are submitted by “friends of the court” with an interest in the case. The solicitor general of the United States represents the government before the Supreme Court. The brief provided by the Solicitor General is routinely read with extra care. The Supreme Court at Work (continued) 21 Oral Argument Each side is given 30 minutes for oral argument, during which time the justices can ask questions as desired. Appearance before the Court is an intimidating experience. Conference and Decision After the oral arguments, the justices meet to discuss the case. If opinions are unclear, a non-binding vote is taken. Conferences are closed to all but the justices, and leaks are rare. The Supreme Court at Work (continued) 22 Assignment and Writing of Opinions An opinion of the Court is an explanation and justification of the decision agreed to by at least a bare majority of the justices. Justices in the minority write dissenting opinions. Concurring opinions are written by majority justices whose reasons differ or who have other thoughts to add. All opinions are published in the United States Reports. The Law Clerks Law clerks (recent law school graduates) assist the justices. Clerks do a variety of jobs and work long hours. The Supreme Court and American Government: An Assessment 23 Judicial Review and Democracy Critics argue that judicial review is antidemocratic because judges invalidate decisions made by elected representatives. Others reply that judicial review checks government power and protects minority rights. Influences on Supreme Court Decision Making A justice’s political ideas can have a strong influence. A justice’s perception of his/her role can have a strong influence. The Supreme Court and American Government: An Assessment (continued) 24 Some justices are result-oriented and view their task as writing political ideas into their decisions. Some justices are process-oriented, concerned with the Court’s place in the democratic process and hesitant to interfere with majority rule. Judicial activists are eager to apply judicial review, while judicial restraints are not. Influences on Supreme Court Decision Making (cont.): Precedents (prior decisions in similar cases) affect justices’ decisions. The Court’s own decision-making process (briefs and oral arguments) shape its decisions. Collegial interaction and conferences affect decisions. Public opinion may influence the actions of the justices. The Supreme Court and American Government: An Assessment (continued) 25 Checks on Judicial Power Constitutional amendments may reverse a Court’s decision. Statutory amendment allows Congress to correct the Court’s interpretation of a statute. Impeachment may be used to remove judges and justices. Congress may withdraw jurisdiction from the Court or change its size. The president may appoint and the Senate may confirm new justices. The Court depends on others for compliance.