CIVIL RIGHTS SOURCE ANALYSIS

advertisement

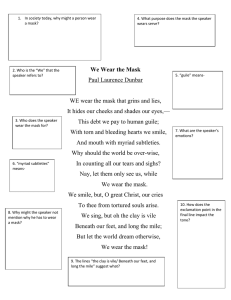

CIVIL RIGHTS SOURCE ANALYSIS Directions: Select TWO poems and TWO excerpts from the sources below that primarily reflect the social climate of the United States during the pre-Civil Rights movement era. Analyze the message and meaning associated with the sources you have selected. Conduct an OPVL analysis as well (Hint: additional information regarding these sources can be found in chapter 17 of Zinn, pages 443-467). “I, Too.” By Langston Hughes: I, too, sing America. I am the darker brother. They send me to eat in the kitchen When company comes, But I laugh, And eat well, And grow strong. Tomorrow, I'll sit at the table When company comes. Nobody'll dare Say to me, "Eat in the kitchen," Then. Besides, They'll see how beautiful I am And be ashamed,-I, too, am America. “Lenox Avenue Mural” By Langston Hughes: What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a soreAnd then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar overlike a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode? “Incident” By Countee Cullen: Once riding in old Baltimore, Heart-filled, head-filled with glee; I saw a Baltimorean Keep looking straight at me. Now I was eight and very small, And he was no whit bigger, And so I smiled, but he poked out His tongue, and called me, "Nigger." I saw the whole of Balimore From May until December; Of all the things that happened there That's all that I remember. “We Wear the Mask” by Laurence Dunbar: WE wear the mask that grins and lies, It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,— This debt we pay to human guile; With torn and bleeding hearts we smile, And mouth with myriad subtleties. Why should the world be over-wise, In counting all our tears and sighs? Nay, let them only see us, while We wear the mask. We smile, but, O great Christ, our cries To thee from tortured souls arise. We sing, but oh the clay is vile Beneath our feet, and long the mile; But let the world dream otherwise, We wear the mask! Excerpt from Black Boy by Richard Wright (1937): The white South said that it knew "niggers," and I was what the white South called a "nigger." Well, the white South had never known me-never known what I thought, what I felt. The white South said that I had a "place" in life. Well, I had never felt my "place"; or, rather, my deepest instincts had always made me reject the "place" to which the white South had assigned me. It had never occurred to me that I was in any way an inferior being. And no word that I had ever heard fall from the lips of southern white men had ever made me really doubt the worth of my own humanity. Writings from Angelo Herndon: All my life I'd been sweated and stepped-on and Jim-Crowed. I lay on my belly in the mines for a few dollars a week, and saw my pay stolen and slashed, and my buddies killed. I lived in the worst section of town, and rode behind the "Colored" signs on streetcars, as though there was something disgusting about me. I heard myself called "nigger" and "darky" and I had to say "Yes, sir" to every white man, whether he had my respect or not. I had always detested it, but I had never known that anything could be done about it. And here, all of a sudden, I had found organizations in which Negroes and whites sat together, and worked together, and knew no difference of race or color… Recollection of his trial – Angleo Herndon: The state of Georgia displayed the literature that had been taken from my room, and read passages of it to the jury. They questioned me in great detail. Did I believe that the bosses and government ought to pay insurance to unemployed workers? That Negroes should have complete equality with white people? Did I believe in the demand for the self- determination of the Black Belt - that the Negro people should be allowed to rule the Black Belt territory, kicking out the white landlords and government officials? Did I feel that the working- class could run the mills and mines and government? That it wasn't necessary to have bosses at all? I told them I believed all of that—and more. . .. Truman’s Committee on Civil Rights: Our position in the post-war world is so vital to the future that our smallest actions have tarreaching effects. .. . We cannot escape the fact that our civil rights record has been an issue in world politics. The world's press and radio are full of it. . ., Those with competing philosophies have stressed-and are shamelessly distorting-our shortcomings. . . . They have tried to prove our democracy an empty fraud, and our nation a consistent oppressor of underprivileged people. This may seem ludicrous to Americans, but it is sufficiently important to worry our friends. The United States is not so strong, the final triumph of the democratic ideal is not so inevitable that we can ignore what the world thinks of us or our record.