Brown

advertisement

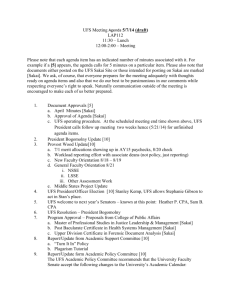

“Conceptualizing Communities in Applied Anthropological Practice using a Social Network Paradigm: Experiences from Lesotho and South Africa.” DAVID TURKON In Lesotho, as elsewhere, people have been pushed socially, economically and spiritually, toward individualism and nuclear family models. • Economically: Rational Man vs Moral Economy. • Spiritually: Individual salvation vs ancestral and kinship responsibilities. • Socially: Citizens vs community members. Day-care. Salang, Mokhotlong District 1991. Factionalism in Lesotho is so severe that it is seen as an obstacle to development, and AIDS has even been proposed as a possible remedy: • HIV and AIDS - “the social crisis that may very well help Basotho to transcend the past as they join hands beyond partisan lines to defeat this new common enemy” (Kimaryo et al. 2003:xl–xli). • Centralization created by technology, transportation and communication have further blurred boundaries that used to provide frameworks for community identity and action (Hayland & Bennett 2005:6-7). • There has been a shift among social scientist to focus on how community based groups react to macro forces (Hayland & Bennett 2005:6-7). Traditional Healers Association meeting (Mokhotlong hospital, 1992) This academic focus on community based groups has not substantially influenced the ways that most international NGOs approach “community level” Interventions. Care Family Health International and World Food Program Nonetheless, our concepts have been usurped • Intervention work is today commonly said to be “culturally tailored” and administered through “indigenous institutions” that serve “the community.” A survey of INGO professionals working in Lesotho identified multiple problems associated development work, including: • Programs are poorly targeted, don’t always reach people with greatest need. • Programming is fragmented (not coordinated across sectors). • Within communities participation is spotty. • Even when people with greatest need are targeted, education stressing importance of conforming to program standards is seldom stressed. (Turkon et al. 2009). Conceptualizing communities • Much social science research focuses on the outcomes of individual behaviors, motivations and other conditions. Behavior, however, does not happen in isolation. Other people, groups and organizations influence individual behavior. We are social beings. NGOs commonly assume communities exist among shared living spaces or demographically similar populations. But: • community members do not share the same roles and rights (e.g. gender, religion, age, ethnicity, kinship, political preferences, class, etc.). • Factions coalesce around interests and issues and embody different resources and degrees and kinds of social capital. Lesotho Irrigation Porject (LIP) • Addresses nutrition and livelihood security through reliable food production in marginal environs. • Water stored in cisterns is available during drought. • Conservation agriculture uses little water and provides good yields on small farms. Administered through Catholic Relief Services LIP selection methods are fairly typical • Identify “community” (village) with resources needed to meet project goals. • Solicited full participation through chief • Use cultural institutions to appeal to symbolism and motivate participation (mosobelo – “traditional” helping and sharing). Participants realized bountiful produce and substantial income from sale of surpluses BUT: • Many villagers did not participate but indicated they would like to. • Participants did not want new members who would dilute benefits. Household Urban Garden (HUG) Selection Methods • Uneven participation: – Some did not receive notification of information meetings or chose not to attend. – Renters thought of “their village” as being where they possess land. Almost all non-participating households expressed desire to participate. Chief showing improvements he made to a “trench” or “raised bed” garden Does the approach used by CRS exacerbate problems it seeks to ameliorate? • To their credit, CRS is concerned about getting selection right and working to do so. • CRS is hampered, however, by: – – – – Short project cycles. High staff turnover (three year rotation). Poor coordination with other NGOs. Inadequate understandings of culture and community. Social Network Paradigm: methods for analyzing structural inequalities by focusing on: • The interconnectedness of people, institutions and locations. • The contexts of life (recognizing people rarely act in isolation). • How people are influenced by groups to which they belong and with whom they interact and communicate. (LeCompte & Schensul 2010:73). Public telephone provider in rural Lesotho Social network analysis can identify, for example: • Sources and flows of power, influence and communication. • Social contexts of people’s lives beyond their individual or family characteristics. • Areas within networks where resources might be available. • Whether individuals are “bound” allegiances or “unbound.” • Risks through association with a network (e.g. contracting STDs) (Trotter et al 2012:198-200, 245). Open vs. Closed Networks • Boundaries of closed network are delineated socially and spatially. You can study all members. • Boundaries of open networks can not be delineated and you can never study all members. • Nevertheless, studying open networks gives us understandings of social forces and dynamics, and of key individuals or core groups that shape the whole and influence the individuals within (Trotter et al 2012:199-201). Social capital is actualized through social networks Ego networks are closed networks that consist of a focal node ("ego") and the nodes to whom ego is directly connected ("alters") plus the ties and the nature of ties. Which nodes seem most isolated? Relational Networks (broad community networks) • Open networks that link communities through exchanges of persons, resources and infrastructure. • Organizations are connected by users, boards of directors, administrators, outreach workers, etc. • Individuals are considered in relation to other individuals and groups. (LeCompte & Schensul 2010:75) Partners In Health, Bobote, Lesotho Bonding and Bridging Networks: o Bonding – Indicate strong social cohesion between like people (boundaries may exist around geography, occupation, ethnicity, culture, class, religion, gender, and so on. o Bridging – Where social boundaries are crossed to forge relationships. Key question: What conditions produce and maintain boundaries at the edges of networks, and can these “blocks” be “bridged” to confront common problems or initiate interventions. Bridging networks may be used to enhance social capital by establishing connections with other people, resources or organizations. “Connectivity” (patterns of information flow) can be characterized by measures such as: • Amount of information that passes through a network. • Who are “gatekeepers” to information. • Graphing differential influence in the group (e.g. centralized, hierarchical or diffuse). • Probabilities that someone will or will not receive information introduced into the network. • Groups at risk (infectious disease, crime victimization, food insecurity, etc.) (Trotter et al 2012:230-231). • Social network analysis identifies sodalities as well as social divisions. • Ethnographic investigation (qualitative research) can reveal the nature of sodalities and divisions. It may be prudent to work with factions until common foci around which community solidarity can be promoted are ethnographically identified or verified (Wayland & Crowder, 2002). Bridging networks to empower agency and mobilize social capital, promotes sodalities and unleashes social immunity. Social Immunity: “Collective resistance against problems” (Mitika 2001) Members of an AIDS caregiving cooperative in Lesotho Social Network Paradigm is useful for: • Identifying group members, patterns of interaction with other members, networks and organizations. • Understanding how network membership influences beliefs and behaviors. • Understanding how cultural, behavioral and technological innovations are transmitted through networks. • Introducing innovations that lead to normative and behavioral change in individuals, groups and wider communities. • Correlating with demographic variables to identify “predictors” of other behaviors or conditions, such as resources, risks, health or mental status (Trotter II et al 2012). The social network paradigm is not just a sophisticated social scientific method. It is a rapidly evolving field that provides a simple way of conceptualizing and thinking about the cultural and social universes we engage with. Applying the Social Network Paradigm to Longitudinal Survey Research • Future Impacts Today: Long Term Consequences of Early Environment (FIT). • Examines multiple influences on childhood development from 19 weeks gestation to 20 years old (biomarkers, education, psychological profiles, family violence, nutrition, genetic profile, etc.). Rationale: • Determine degrees to which participants benefit from social capital by gauging: – Degrees to which individuals are connected to support networks through bonding and bridging networks. – Are networks open or closed? – Does each network embody emotional support, material support, cooperative support, information, etc. – Does a network provide support, extract support, or both? Utility: • This approach will allow us to: – Explore beyond individual social and psychological characteristics to establish social contextual elements within which people spend much of their lives interacting with groups around them. – Treat these characteristics as variables that describe network characteristics in ways similar to demographic variables (Trotter et al 2013: 202, 198). – Add social context to individual or household centered research instruments. Methodology I • Focus groups to determine: – Types of networks (kinship, cooperatives, religious, political, clubs and societies, etc.). – Open vs Closed. – Bridging vs. bonding. – Strengths and weaknesses of networks. Methodology II • Research Instrument: – Provide comparative picture of relational ties to correlate with other outcomes. – Administered at outset and at benchmarks to determine changes in network relations and degrees of social capital. – Determine degree to which social connectedness (social capital) affects developmental health determined by other measures. UFS Interdisciplinary Research Proposal: Future Impact Today Confirmation of participation by UFS and other collaborators Researchers/ Groups: Department E-mail address Themes Signature Nutrition and Dietetics walshcm@ufs.ac.za Biomarkers for growth Dr L vd Berg (Louise) vdbergvl@ufs.ac.za Dietary intake Me L Janse van Rensburg JanseVanRensburgL1@ufs.ac.z Biomarkers related to macro- (Liska) a and micro-nutrients Health Sciences: Prof CM Walsh (Corinna) Mrs M Jordaan (Marizeth) Anthropometry Dr L Meko (Lucia) Prof P Wessels (Paul) Obstetrics and Gynaecology CronjeEM@ufs.ac.za Knowledge and attitudes with MekoNML@ufs.ac.za regard to breastfeeding phwessels@mweb.co.za Vitamin A, D and iron status in relation to pregnancy outcome Fetal growth in relation to maternal micronutrient status Pelvic floor dysfunction Anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) and its association with lifestyle habits and medical conditions Prof C Viljoen (Chris) Haematology and Cell viljoenCD@ufs.ac.za Genetic testing (Hypertension) and Cell bothaGM@ufs.ac.za Genetic testing (Diabetes) Biology Dr GM Marx (Gerda) Haematology Biology Prof SM Meiring (Muriel) Haematology and Cell Biology gnhmsmm@ufs.ac.za Micro-nutrient-deficiency and ADAMTS13 status Me M Visser (Marieta) Occupational Therapy visserMM@ufs.ac.za Neurodevelopmental trajectories from birth to 60 months Dr S van Zyl (Sanet) Basic Medical Sciences gnfssvz@ufs.ac.za Dr L van der Merwe (Lynette) Links between early adversity and chronic diseases of lifestyle, impairment of immune status, cardiovascular and metabolic function Dr M Reid (Marianne) School of Nursing reidM@ufs.ac.za Health literacy of pregnant women with Diabetes Dr D Botha (Delene) School of Nursing bothaDE@ufs.ac.za Incidence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in preterm labour Dr L Holtzhausen (Louis) Sport and Exercise Medicine holtzhausenLJ@ufs.ac.za Physical activity Prof Andre Venter (Andre) Paediatrics and Child Health Care gnpdav@ufs.ac.za ADHD Dr S-J Smith (Sarah-Jane) SmithSJ@ufs.ac.za Malnutrition Dr U Hallbauer (Ute) HallbUte@ufs.ac.za HIV and TB; Morbidity and mortality Postnatal depression Dr A Groenewoud (Annelise) GroenewoudA@ufs.ac.za Dr D Griesel (David) GriesselDJ@ufs.ac.za Dr PM van Zyl (Paulina) Pharmacology vzylpm@ufs.ac.za Autistic spectrum disorder Contribution of the acetaldehyde production capacity of maternal salivary microflora and microflora in colostrum to the acetaldehyde production capacity of salivary microflora of the neonate Dr PM van Zyl (Paulina) Pharmacology vzylpm@ufs.ac.za Contribution production of the acetaldehyde capacity of maternal salivary microflora and microflora in colostrum to production the acetaldehyde capacity of salivary microflora of the neonate Other departments/ universities Dr Z Hattingh (Zorada) CUT hattingz@cut.ac.za Geophagic practices of pregnant and lactating women Dr D Himmelgreen (David) University of South Florida dhimmelg@usf.edu Household food security status in relation to food-related making, nutritional decisionstatus (anthropomentric and dietary), and mental health (physiological and and stress psychometric measures) Dr D Turkon (Dave) Ithaca dturkon@ithaca.edu Participation in social networks and it’s relation with physical and mental development of children Prof L Marais (Lochner) Centre for Development Support, UFS MaraisJGL@ufs.ac.za Influence of urbanity on health profiles Illustration of Social Networks through Facebook • http://www.facebook.com/apps/application.p hp?id=3267890192 References Hayland, S. and L. Bennett (2005) Introduction. In, Community Building in the Twenty-First Century, S. Hyland Ed. SantaFe: School of American Research Press. Kimaryo, Scholastica Sylvan, Joseph O. Okpaku, Sr., Anne Githuku-Shongwe and Joseph Feeney (2003) Turning a Crisis into an Opportunity: Strategies for Scaling Up the National Response to the HIV/AIDS Pandemic in Lesotho. Maseru, Lesotho: The Expanded Theme Group on HIV/AIDS c/o United Nations Development Program, United Nations House. LeCompte, Margaret & Jean Schensul (2010) Designing and Conducting Ethnographic Research. Rowman and Littlefield, Altamira Press. Mitika, Mike Mathambo (2001) The AIDS Epidemic in Malawi and its Threat to Household Food Security. Human Organization, 60(2):178-188 Trotter II, Robert, Jean Schensul and Margaret Weeks (2012) Conducting Ethnographic Network Studies: Friends, Relatives and Relevant Others. In, Specialized Ethnographic Methods: A Mixed Methods Approach. Jean J. Schensul and Margaret D. LeCompte, eds. Rowman and Littlefield, Altamira Press. Turkon, D., Himmelgreen, D., Rmero-Daza, N. & C. Noble (2009) Anthropological perspectives on the challenges to monitoring and evaluating HIV and AIDS Programming in Lesotho. African Journal of AIDS Research 2009, 8(4). Wayland, C. & Crowder, J. (2002) Disparate views of community in primary health care: understanding how perceptions influence success. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 16(2). Yaffee, R. (2003) ‘A primer for panel data analysis.’ In: Connect: Information Technology at NYU [online]. Fall 2003 Edition. New York, New York University Information technology Services. Available at: <http://www.nyu.edu/its/pubs/connect/fall03/yaffee_primer.html>