A radical change is taking place in the development of our

advertisement

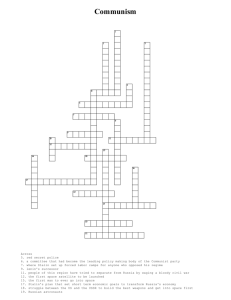

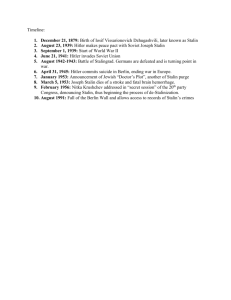

Comrade Mona Malamiri Modern History Oral: Russia and the USSR “Why did Stalin introduce collectivisation and industrialisation, and how did these policies impact the Soviet State?” Comrade Mona Malamiri Modern History Oral: Russia and the USSR “A radical change is taking place in the development of our agriculture from small, backward individual farming. We are advancing full steam ahead along the path of industrialisation to Socialism, leaving behind the age-long ‘Russian’ backwardness. We are becoming a country of metal, a country of cars, a country of tractors, and when we have put the USSR in a car, and a peasant on a tractor, let the capitalists try to overtake us1.” By November 1929, Russian dictator Joseph Stalin had successfully removed his rivals, obtained supreme power and was introducing plans of collectivisation and industrialisation, aimed at promoting rapid economic growth and ridding the Soviet of its backward state. These policies, however, instigated conflict between the populace and the Man of Steel himself, whose brutality and lack of concern for the welfare of the people allowed him advance his socialist dictatorship. Good afternoon Mrs. Hufton and comrades, Stalin’s ultimate objective was to turn the Soviet Union into a modern industrial power, secure from foreign capitalist invasion. However, Stalin was in a similar position to that of his predecessors: the inefficiency of agriculture was proving a hindrance in his efforts to expand Russian industry. It was essential that agriculture was modernized in order to finance the industrialisation drive. There had to be enough food to feed the workers and for export in exchange for technology and raw materials. Stalin felt that drastic change was needed in order to maintain power hence, in 1929, decisions were made that agriculture would once again be centralised under government control. He introduced collectivisation, confident that the replacement of privately-owned peasant farms by larger, more manageable collective farms, or kolkhozy, would immediately increase food supplies for urban populations, the supply of raw materials for industry, and agricultural exports. While collectivism was extremely successful in consolidating Stalin’s power, it was unpopular amongst the peasantry and had devastating repercussions. As described by historian Sheila Fitzpatrick, the mentality of the peasantry was that of “resistance to change.2” Seen as a revival of serfdom, resentment towards the kolkhozy was expressed through the destruction of crops, equipment and farm buildings, and the slaughtering of livestock. Stalin’s response to resistance was, of course, brutal. Methods of coercion in the form of terror were used against people resisting collectivisation. There was scant regard for the interests of the peasants, with soldiers ordered to imprison, shoot or deport peasants who did not comply with the policy. The introduction of collectivisation is describes by historian Peter Kenez as a “declaration of war against peasantry.3” Supporting his theory is Russian historian Geoffrey Hosking, stating that “collectivisation destroyed the structure of the traditional Russian village, bequeathed a 1 Extract from speech by Stalin explaining his policy of collectivisation (November 1929) Ingram, Philip. (1997). Russia and the USSR 1905-1991. University Press: Cambridge 2 Fitzpatrick, Sheila. (1996). Stalin's Peasants: Resistance and Survival in the Russian Village after Collectivization. Oxford University Press: Oxford. 3 Kenez, Peter. (1999). A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. Comrade Mona Malamiri Modern History Oral: Russia and the USSR demoralized rural population…4” These views exemplify not only the broken relations between the government and the peasantry under Stalin’s rule, but also the damage brought on by collectivisation. The introduction of the New Economic Policy had seen the growth of a class of slightly better-off peasants or kulaks who Stalin saw as the ‘enemy to communism’ and hoped to exterminate through collectivisation. Stalin used kulaks as scapegoat to show other peasants that opposition to the government would not be tolerated. Kulaks suffered the worst from collectivisation, as unlike poor peasants who had nothing to lose under the policy, kulaks saw all they had worked for simply being taken away. As stated by American historian David Christian, “…for most peasants, collectivisation was a disaster.5” The destruction and disruption caused by collectivisation led to a widespread famine. Although harvests were extremely low, Stalin continued to collect grain from famine stricken areas to sell overseas. He ignored the cries of the peasants, resulting in 5 million starving to death between 1931 and 1933. An eyewitness account describes how “the peasants ate dogs, horses, rotten potatoes, the bark of trees, grass – anything they could find … cannibalism was not uncommon.6” Historian R. W. Davies notes that the policy “was enforced in spite of famine in the countryside,” believing that the aim of collectivisation was merely to “strengthen central power and repressive apparatus.7” Soviet historian, Lyudmila Saraskina, agrees with Davies that collectivisation was a “monstrous means of the seizure of absolute power… that Stalin really wanted.8” Agricultural productivity has seen a 65% increase in 1941 from that of 1930, proving the success of collectivisation. While there had been social unrest and severe food shortages, Stalin’s policy had helped in the consolidation of communism in Russia and had tightened his hold on power. Stalin’s idea of ‘Socialism in one country’ provided the basis on which industrialisation was to be enhanced. Industrialisation was primarily aimed at shifting the Soviet from an agrarian-based economy to a modern, self sufficient industrialist nation. Stalin was worried that if the USSR did not catch up to the Western industrialised standards, they would be vulnerable to capitalist invasion. Industrialisation was hence to become Russia’s main priority with the working class to be increased. Stalin believed the Five-Year Plans were the only way to rapidly industrialise. He developed a total of 3 Five-Year Plans, each focusing on specific industries. The first aimed at expanding heavy industry, emphasized the production of coal, oil, iron, steel and electricity. The second concentrated on the production of machinery, particularly tractors for the collective farms, whilst the third aimed at producing consumer goods. 4 Hosking, Geoffrey. (2002). Russia and the Russians: From Earliest Times to 2001. Penguin: London. 5 Christian, David. (1997). Power and Privilege: Russia and the Soviet Union. Palgrave Macmillan: United Kingdom. From: Proctor, Helen. (1995). Ruling Russia – from Nicholas II to Stalin. Longman Australia: Melbourne. 6 7 Davies, R.W. (1990). From Tsarism to the New Economic Policy: Continuity and Change in the Economy of the USSR. Macmillan: London. 8 From: Ingram, Philip. (1997). Russia and the USSR 1905-1991. University Press: Cambridge Comrade Mona Malamiri Modern History Oral: Russia and the USSR He gained the support of the nation through the use of widespread propaganda aimed at encouraging hard work. Triumphs of the Soviet development were published and the promotions of future projects, such as the Trans-Siberian railway, were conveyed through propaganda as a reminder of the successes that would come with industrialization. Overall, the Five-Year Plans were a success for Russia. The plans had seen an increase in industrial output, economic stability and export profits, whilst workplace productivity was at a high. By 1939, the USSR was transformed into one of the most advanced industrial countries in the world from its backward state in 1928. Not only had industrialisation brought on mass urbanization and an increased stability in employment rates, but it had also seen the economic consolidation of communism in the Soviet. Historian E.H. Carr’s assessment of Stalin’s rapid industrialisation is that of “monumental achievement, monstrous price.” However, R. W. Davies believes that although Stalin “triumphed in planned industrialisation9” the policy “would be considered necessary if the aim was to create conflict.10” The negative implications of industrialisation were primarily due to a decrease in working and living standards. Wages were extremely low, working conditions often hazardous, and housing was in very short supply. Stalin set targets for industrial growth purposely high to encourage perseverance by the workers. Workplace discipline became very strict, with regular absence resulting in the loss of rations and commodity cards. The first Five-Year Plan itself was harsh on industrial workers, with the emphasis being on the fulfillment of quotas and failure to reach targets resulting in severe punishments. In regards to the first and second five-year plans, British professor Martin McCauley comments that given the huge sacrifices, the annual growth was “modest, and arguably could have been achieved by adopting more traditional methods.” However, this conflicts with the perspective of Russian historian Alexander Gershchenkron, who states that “the 1890’s marked the beginnings of the Russian Industrial Revolution…however it took 30 years for the right man to step up and take action on the matter.11” Joseph Stalin’s collectivisation and industrialisation policies were necessary for economic and social growth within the Soviet State. Stalin’s implementation of these policies saw Russia prosper and modernize, leaving behind Russian ‘backwardness’ whilst consolidating communism in the Soviet. Though with negative impacts on the people of Russia, especially the peasantry, economy rapidly advanced and Russia was able to gain a place on the industrialised world stage. Stalin had taken a gamble but had transformed Russia into a state stronger than ever before. Thank you. 9 Davies, R.W. (1990). From Tsarism to the New Economic Policy: Continuity and Change in the Economy of the USSR. Macmillan: London. 10 Ibid. 11 Gershenkron, Alexander. (1962). Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective: A Book of Essays. Harvard University Press: USA.