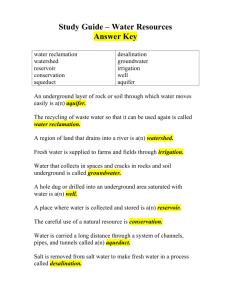

- Sacramento

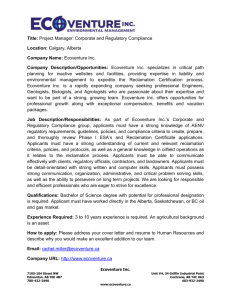

advertisement