Heading towards a new international approach to crises and

advertisement

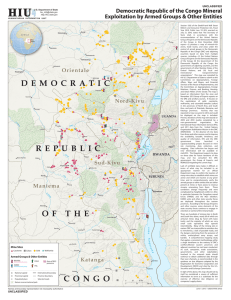

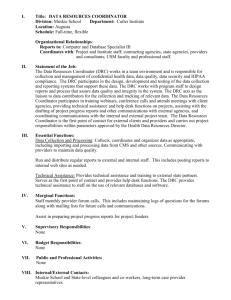

Heading towards a new international approach to crises and conflict management? The case of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Gérard Gerold, Associate Researcher, Fondation pour la recherche stratégique Translation: Alexander Bramble The threat of Islamist fighters taking control of Bamako in December 2012, and the attack on the Westgate shopping centre in Nairobi by members of al-Shabbaab on the 21st September 2013, seem to have accelerated the shift in the evaluation of events and crises in Africa and to have modified the international community’s previous approach, in place since the beginning of the century, to conflict management and re-establishing peace in this part of the world. As a broad outline, the previously political, institutional, and developmental approach has given way to a military and security-related attitude that scrutinises countries and regions in terms of the risks they harbour and the most effective responses. Multilateral and multi-dimensional peacekeeping and statebuilding operations, launched in the euphoria of the immediate aftermath of the end of the Cold War, have been progressively replaced by “regional stabilisation” operations that draw more heavily on the objectives of fighting terrorism or armed groups than major principles of law. The primary objective is now to build security partnerships, most often bilateral, which provide intelligence, operational support, and boots on the ground where necessary, and, beyond that, forging alliances to “contain” the terrorist threat. From MONUC to MONUSCO; from ambition to stabilisation At the beginning of the century, the DRC was the test site for an ambitious policy to resolve conflicts and reconstruct a “failed State”, through an operation conducted by the United Nations – MONUC – on behalf of the international community. After more than fifteen years on the ground, results that are constantly called into question by the government, and repeated episodes of military humiliation, this operation, which became MONUSCO in June 2010, no longer has many supporters in diplomatic missions and in New York. It seems, in fact, to have abandoned its political and institutional ambitions over the years, falling back on a security mission in the east of the country, thus accepting the organisation by Congolese authorities of an irregular election in 2011, and to have failed in its duty to protect populations and human-rights defenders. These criticisms are both the recognition of an ageing mission that has difficulties in fulfilling its mandate, and the result of a change of approach to the Congolese and regional crisis by the international community, and particularly by its western component, the United States, France, and the United Kingdom. The desire to establish democratic institutions in the country and to institute new economic governance has, it seems, given way to the policy of “stabilisation”, which takes care above all to avoid trouble along borders and the emergence of lawless areas. The international community has given, at least until now, the impression of contenting itself with maintaining the status quo and a few blows against the “spoilers” 1, which provide the added advantage of being more mediatised than a long and difficult effort to change the nature of governance. In the region, the countries that have stable regimes and credible armed forces and intelligence services remain partners; the 1 Fifteen years of crisis management in the DRC provide, with some nuances, a fairly good example of the change that has occurred. This term is generally used within international bodies to categorise the politico-military groups at odds with the governments of the day, and responsible for national or regional destabilisation. Dakar International Forum on Peace and Security in Africa 47 DRC, which has none of the above, claims to run the risk of gradually disappearing from the top of the international agenda and seeing its institutional and political reconstruction left fallow. The Addis-Ababa Agreement: the last, short-lived, attempt at an overarching solution Presented at the start of 2013 as the reaffirmation of the international community’s desire to find lasting solutions to the region’s problems, and above all as the implementation of an overarching strategy, the Framework Agreement gave rise, notably following the swift victory against the M-23 rebellion in November 2013, to the hope of a definitive resolution of the Congolese crisis through a series of regional agreements and the commitment by the Congolese government to conduct profound political and security reforms and to have a more transparent election process in 2015. Coupled with two followup mechanisms placed under the direction of two leading figures, notably Mary Robinson, UN Special Envoy to the Great Lakes region, the Framework Agreement furthermore presented the novelty of directly involving regional actors in the resolution of the crisis. Alas, over the past six months, the application of the Agreement has broken down. The eternal problem of the disarmament of the FDLR 2 is dividing the signatories, national economic interests and diverging strategic development choices are fracturing regional organisations 3, the political pressure that is vital to the implementation of the commitments undertaken is no longer being applied, and Mary Robinson finally abandoned the task to a successor who set up base, along with the rest of his team, far away from the field. The UN Secretary General’s assessment in his latest report to the Security Council 4 is irrevocable: the Framework Agreement is not being applied, none of the structural reforms, on standby in Kinshasa for many years, is being seriously undertaken, and the armed groups are far from having been neutralised. The grave deterioration of the security situation in the Beni region, which is currently unfolding, further corroborates this damning diagnosis. A new strategic approach that risks reinforcing countries with strong armies It very much seems that the political imperatives of regional stabilisation and the “war on terrorism”, along with the worsening of the threats in central Africa – al Shabbaab’s penetration into Uganda and Kenya, the expansion of Boko Haram, and the appearance in the Central African Republic of Islamist groups of fighters – have got the better of the commitments undertaken in Addis-Ababa. The United States is now above all concerned with strengthening its partnerships with Uganda, Rwanda, and Kenya, whose armed forces, intelligence services, and national police forces are the beneficiaries of ever more substantial support. The United Nations is feting the fact that some of these countries, along with Burundi, have, in the framework of AMISOM 5, committed themselves on the front line of the extremely difficult fight against the Somalian Islamists. Moreover, the UN, along with the United States and European countries, is supporting the creation of the future “East African Standby Force” whose formation is provided for by the African Union in the framework of its peace and security policy, and of which the armed forces of these countries, along with those of Ethiopia, will constitute the backbone. The indirect consequence of this policy focused on stabilisation, the political status quo, and security priorities, is to contribute to the 2 The Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda 4 3 5 ICGLR, EAC, SADC th See document S/2014/698 of the 25 September 2014 48 Dakar International Forum on Peace and Security in Africa African Union Mission to Somalia continuation, and sometimes to the reinforcement, of political regimes in the region and in the DRC that have little democratic legitimacy and which are regularly criticised for their mode of governance. As such, the rescue of the Kabila regime in November 2013 by the International Intervention Brigade was not offset by any form of compensation in terms of political openness or the acceleration of reforms. On the contrary, the Congolese government expelled the leading UN human rights official, Scott Campbell. The political agendas of the DRC and the three other countries in the region6 are marked by the important electoral deadlines. They could be an opportunity for the international community to change its perspective on what constitutes stability in the Great Lakes region. Questions to address at the Dakar Forum: • In light of the failure to implement the Framework Agreement, what lessons can be learned from the involvement of the countries and organisations in the region? Does joint management of regional crises have its limits? • Are the magnification of crises of legitimacy of regimes in power and the preparation of new scenarios for violence not by-products of stabilisation policies? • Faced with the next electoral deadlines in the countries in the region, what position should be adopted with regard to the authorities in situ without undermining the credibility of international action to support the establishment of the rule of law? • How can an effective fight against terrorism be reconciled with the necessary strengthening of democratic institutions in the African countries in question? 6 Presidential elections are scheduled to take place in June/July 2015 in Burundi, in July and December 2016 in the Congo and in the DRC, and finally in Rwanda in August 2017 Dakar International Forum on Peace and Security in Africa 49