Transportation & Infrastructure Finance in the States

advertisement

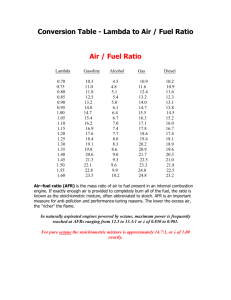

Presentation to Arkansas Blue Ribbon Committee on Highway Finance September 16, 2009 by Sean Slone Transportation Policy Analyst The Council of State Governments Founded in 1933 Serves the executive, judicial & legislative branches of state government through leadership education, research and information services Regionally-based, non-partisan forum Headquartered in Lexington, KY with regional offices in New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Sacramento, Washington America’s infrastructure crumbling 5-year investment of $2.2 trillion needed Needed annually to improve the nation’s highways: $186 billion Current spending for highway capital improvements: $70.3 billion ARRA funding for transportation infrastructure projects: $48.1 billion 82% of federal transportation funding comes from federal fuel taxes 24% of state revenues for highways come from state fuel taxes Motor fuel tax revenues continue to decline Purchasing power has declined No longer sufficient to finance large and growing infrastructure needs Converting from Cents Per Gallon Excise Taxes to an ad valorem tax Indexing the fuel tax to some appropriate indicator such as the Consumer Price Index or the Construction Cost Index Several states adopted “variable rate” fuel taxes between 1974 and 1982. Fuel prices fell rapidly in the 1980s and fuel tax revenues pegged to the price of fuel also produced dramatic reductions in revenue. Michigan is the oft-cited example. About 15 states enacted some form of indexing in the seventies or early eighties; most reversed themselves Indexing only a portion of the motor fuel tax Coupling indexing with a “cap” on annual changes in the upward or downward direction in order to avoid wild fluctuations in tax revenue and in prices faced by consumers Six states index their gasoline taxes to inflation. Florida and Maine adjust gas taxes by the CPI. Nebraska adjusts gas taxes by a state funding formula. Kentucky, North Carolina and West Virginia link their gas taxes to the fuel wholesale price. Nine states also add a sales tax to gasoline purchases or tax fuel distributors or suppliers. Oregon enacted a law to increase fuel taxes by 25 percent and to raise registration, title and driver’s license fees. Only three jurisdictions have enacted gas tax increases this year; Vermont and D.C. are the other two. Minnesota increased their gas tax for the fourth time in 15 months this summer as part of a graduated increase approved by lawmakers last year. Fifteen states considered raising state fuel taxes, motor vehicle fees , or both this year. Tennessee’s gas tax of 21.4 cents per gallon has not been raised in 20 years. Relatively inexpensive to administer in relation to potential yield Can be varied by vehicle size Can be set in rough relation to highway cost responsibility Categorized as “very promising” as both a short- and long-term funding option Types: heavy truck fees, excise taxes on vehicle sales, personal property taxes Development Impact Fees Special Assessments Tax Increment Financing Community Facilities Districts Rental Car Taxes Cigarette Taxes Gambling/Lottery Revenues Colorado hiked vehicle registration fees to raise about $250 million a year for transportation. Iowa lawmakers agreed to Gov. Culver’s plan to borrow $830 million, with the bonds paid off from casino gambling profits. Illinois financed a $31 billion construction program by legalizing video poker, raising fees and hiking taxes on candy, beauty products and alcohol. North Carolina lawmakers approved legislation to allow counties to increase their sales taxes to support transportation projects. Every state except South Dakota, Tennessee and Wyoming has authority to issue state transportation bonds. Bond funding provides states upfront capital to accelerate project delivery. New state bond obligations in 2007 were valued at $19.8 billion. At the end of 2006, outstanding state bond obligations reached a record $96.5 billion. As credit markets have tightened, states seeking to issue bonds or access credit and private capital have encountered challenges. State Credit Assistance Federal Credit Assistance GARVEE Bonds Section 129(a) Loans Private Activity Bonds Build America Bonds Recovery Zone Bonds Authorized by Congress in 1995 In 35 states and Puerto Rico Allow for leveraging of federal and state resources by lending rather than granting federal-aid funds Can be used to attract non-federal public and private investment Revenues from loan repayment and interest are used to fund subsequent loans Vary widely in size, from less than $1 million to more than $100 million South Carolina is the leader in SIB financing Interest rate is set by the state Maximum loan term is 35 years State may be willing to take more risk than a commercial bank would for a project with significant public benefits A state infrastructure bank loan can make a large project affordable by allowing for smaller annual payments States lacked legislative authority to leverage their funds and increase the capitalization level of the bank Complexity of federal requirements Requirements for smaller projects can delay construction schedules and increase costs Insufficient demand for loans due to limited marketing efforts Public-Private Partnerships Tolling Congestion Pricing Vehicle Miles Traveled Charges Collaborations between governments and private companies that aim to improve public services and infrastructure by capturing efficiencies associated with private sector involvement while maintaining the public accountability of government involvement Full-Service Long-Term Concession or Lease Multimodal Agreement Joint Development or Transit-Oriented Development Build-Own-Operate Build-Operate-Transfer or Design-Build-OperateMaintain Design-Build-Finance-Operate Design-Build with Warranty Design-Build Design-Bid-Build Construction Manager at Risk Fee-Based Contract Services & Maintenance More capital can be raised for a project Operating risk shifted to private investors and operators Costs and risks to taxpayers minimized Help taxpayers unlock the inherent value in toll roads lost under government ownership Maximize the strengths of both the public and private sectors Take advantage of the more businesslike approach of private sector firms Private firms quicker to adopt cost-saving and customerservice oriented technology Take advantage of the private sector’s diversified knowledge and awareness of new methods in design, construction, operations and maintenance Transparency & public participation Use of concessions Conflicts of interest Better value for the money Private partner must adequately maintain No non-compete clauses Facility will revert to the state Capping the rate of toll increases Revenue-sharing Length of agreement term More than 5,000 miles of roads, bridges and tunnels in the United States are tolled. State and local governments used $6.6 billion in toll revenues for highway investments in 2004 (7% of total revenues). Increasing tolling on existing roads may be a challenging proposition. Tolling on new roads or when adding additional lanes hold potential for generating new revenue. Legislators in Nevada rejected the state Department of Transportation’s requests to have authority to pursue toll roads and public/private partnerships. Texas failed to act to extend the state DOT’s ability to enter into new P3s. Arizona and North Carolina’s Governors signed legislation allowing their state DOTs to enter into P3s. West Virginia Turnpike increased tolls this year for the first time in 28 years. Toll opponents in Massachusetts have filed ballot measures to eliminate all turnpike, tunnel and bridge tolls in the state. Mechanism that seeks to assess vehicles for the costs they impose on society, which may include time costs, external congestion costs and other variable costs, such as environmental and governmental Types include: tolling the entire roadway, tolling existing lanes, tolling new capacity, imposing a “cordon fee” on any vehicle that enters a designated area. Easy to implement Affordable and feasible administratively Makes enforcement more effective Manages demand on congested facilities, thereby reducing traffic Can generate additional revenues that could be used to expand highway and transit capacity in the corridor to further reduce congestion Encourages the use of other routes and other modes of travel, such as public transportation Impact on lower-income commuters Drivers unable to accept the notion that they should be charged for congestion and don’t want to pay for roads currently free Commuters feel they already “pay” for congestion through delays and stress. Commuters don’t consider traffic conditions to be bad enough to warrant congestion pricing Privacy concerns Fee based on miles driven in the state, collected at gas stations Oregon conducted a year-long pilot project; other states have ongoing research projects GPS-based receiver estimates miles driven in different zones Mileage data transmitted wirelessly to receivers at gas stations Revenues directly reflect the amount of travel VMT-based fees are in place in Europe Technological and institutional challenges remain University of Minnesota added to the body of evidence recently NCHRP also recently addressed strategies for shifting to VMT Three national commissions have said U.S. should adopt a mileage-based approach Premature to rule out other types of taxes and fees to supplement traditional fuel tax revenues Revenue potential Sustainability Political viability Ease/cost of implementation Ease of compliance Ease/cost of administration Level of government Promotes efficient use Promotes efficient investment Promotes safe and effective system operations/management Address externalities Minimize distortions Promotes spatial equity Promotes social equity Promotes generational equity Sean Slone Transportation Policy Analyst The Council of State Governments sslone@csg.org (859)244-8234