Margit Kaffka

advertisement

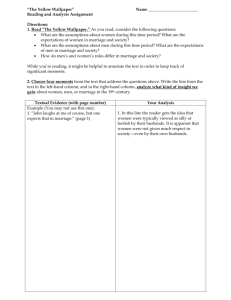

New Women in Hungarian literature: Margit Kaffka 1880-1918 The evaluation of women’s writing • ‘Not even the most outstanding among them [of the women writers] reach the level of value of the really talented male writer. Our judgment so far has also been a merely relative assessment since it will take them a long time before they reach the prominent strength, depth and value of the male writer.’ [István Boross on women’s writing, 1930s ] Margit Kaffka portrait Map of Hungary Biography • 1880 Nagykároly/Carei • Public prosecutor father, impoverished landed gentry • Sisters of Mercy Teacher Training College in Szatmár • Erzsébet Girls’ School, Budapest • 1904 Qualifies as a high school teacher, Miskolc • 1905 marriage Biography 2 • 1907: move to Budapest • 1910: divorce, single-handed support of her son, secondary school teaching • 1914-1918: marriage to Ervin Bauer, brother of Béla Balázs, librettist of Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle Beginning to write • ‘Sister, your daughter’s poems are not bad at all, rather, they are good and beautiful. But for what would a woman write? It would be a shame if the daughter of a good housekeeper like yourself decides not to stick to the wooden spoon. That she is training to be a teacher is also a shame.’ An uncle on Kaffka’s early poems Kaffka’s works Poetry: 1903: Versek [Poems] 1906: Kaffka Margit könyve [MK’s book] 1911: Tallózó évek [Browsing years] 1912: Utolszor a lyrán [The last time on the lyra] 1918: Az élet útján [On the journey of life] Kaffka’s works Short stories: 1905: Levelek a zárdából [Letters from the convent] 1906: A gondolkodók [The thinkers] 1910: Csendes válságok [Quiet crises] 1911: Csonka regény [Trump novel] 1912: Süppedő talajon [On sinking ground] 1914: Szent Ildefonsó bálja [The ball of St Ildefonso] 1916: Két nyár [Two summers] 1918: A révnél [At the ferry] Kaffka’s works Novels: 1912: Színek és évek/Colours and years (1999) 1913: Mária évei [Mária’s years] 1917: Állomások [Stations] 1918: Hangyaboly/The Ant Heap (1995) Nyugat • A significant connection: regular contributor to Nyugat, belonging to the social-literary ferment of the early 20th century • Earlier: support from Budapest publishing houses: embraced by Nyugat in 1908 Nyugat [West] • 1908-1941 • Hungarian literary and cultural periodical responsible for the renewal of Hungarian literature: ‘new songs of new times’ • Also responsible for introducing recent English, German and French poetry in poetic translation The predicament of the woman writer • ‘Maybe now it will be a little better; my grandmother will come to keep house, and in the new flat I will have four walls of my own (each of them one meter long!) among which I can huddle with some sense of privacy.’ Kaffka, 1908 Colours and years (1911) • The predicament of the woman in late 19th century Hungary • Strongly autobiographical work, based on the life story of her mother • Historical identifier: • During the prime ministry of Tisza (18751890); the archduke’s visit in the mid1880s Women’s choices Magda Pórtelky’s life is defined by her marriages 1. Girlhood in Grandmother’s house until marriage 1-approximately age 19 2. The Vodicska marriage: first year omitted, the second year is the focus of action -- about 6 years of marriage until the suicide of the first husband -- age 26 3. Looking for and not finding her place in society; in Budapest, at the mother’s house, and return to Szinyér where she marries the second husband -- age 30 4. The Horváth marriage, 17 years -- age 47 Internal tensions within Magda • Ambivalence about the Vodicska marriage: ‘conquest and dance’ is disproportionate to the aftermath • ‘At the end of that winter she already had some scheme for me to marry the lame Elemér Kendy, who had eleven hundred acres in view … That was the first time I was overwhelmed with a sudden feeling of despair at my helpless state; as a girl, I was at the mercy of others.’ [52] Women in marriage • ‘I felt a great burgeoning desire to undertake this role. Yes, of all occupations this was the one for me, for this was something I understood and had been brought up to do, running a household, a woman’s work in the home.’[172] Women in relationships • The story of widows (grandmother; mother; Magda) • The strong widow: Grandmother • The weak widow: Mother Klári, Magda • Women in relationships: Mother Klári (ineffectual, unable to save family from financial disaster) • Magda: Ineffectual, unable to save families from financial disasters Women in marriage • Aunt Piroska: the life of the village gentry • ‘My Aunt Piroska would spend half the day out of sight in the apiary … The dairy, the barnyard poultry, the orchard, and the bargaining with the market-women took up all my aunt’s time and energy, meanwhile she had a new infant every year’ [55-56; also 163-164] Women in marriage • Aunt Marika • ‘penny-pinching, constricted, petty official’s lifestyle’ [150] • ‘what a proper little pen-pusher he had become, the former lively, jaunty, leathergaitered young gentleman who gambled away the last of his little estate at cards when he was already married to Marika’ [154] Women’s powerlessness within marriage Men as failed providers: • Magda’s father • Vodicska: loses election, accummulates debts, eventually commits suicide • Horváth: inability to care and provide for his family - spendthrift and gambler • Telegdy: improvident, loses his own and his wife’s estate Magda’s inability to consider alternatives • Brief alternative in the ‘sinful city’- actress? • Brief alternative in the villagepostmistress? • Brief alternative in the uncle’s househousekeeper? So, what should a woman choose? • Telegdy: the vision of the ideal woman in the new world pp. 142-143 • ‘The age of independent, strong women capable of fighting is coming, women who can stand firm even in trouble, responsible for themselves and for those entrusted to them by nature, as mothers.’ • Telegdy: the vision of the ideal woman pp. 212-213 • ‘The woman will always remain inferior … two-thirds of their life-span are occupied with unconscious animal cares and duties that go with the maintenance of humankind, and instincts that guide the intellect.’ Magda’s daughters • more educated than their mother • ‘The youngest is eighteen years old now, preparing for her diploma, struggling hard, giving lessons and begging funds for herself, poor thing. Yet all the same she writes, and sometimes I feel that she may be right, that her life is a more honest life, and her youth is a more honest youth.’ [55] Page references to: Kaffka, Margit. Colours and years, trans. by George F. Cushing. Budapest: Corvina, 1999. Secondary sources • Brunauer, Dalma H., "A Woman's Self-Liberation: The Story of Margit Kaffka (18801918)," Canadian-American Review of Hungarian Studies vol.2 , Fall 1978, pp. 31-42. • Brunauer, Dalma H. "The Woman Writer in a Changing Society," Journal of Evolutionary Psychology vol. 9, n. 3-4, 1982. • Czigány, Lóránt, "Women in Revolt: Margit Kaffka" in The Oxford History of Hungarian Literature, Oxford: Clarendon, 1984. pp. 333-36. http://mek.niif.hu/02000/02042/html/47.html • Reményi, Joseph, "Margit Kaffka, Poet and Novelist, 1880-1918," Hungarian Writers and Literature, New Brunswick-New Jersey: Rutgers UP, 1964. pp. 284-91. • Zepetnek, Steven Tötösy de. “Margit Kaffka and Dorothy Richardson: A comparison,” Hungarian Studies, 1996, http://www.epa.oszk.hu/01400/01462/00018/pdf/003-012.pdf • Uglow, Jennifer S., comp, and ed. "Kaffka, Margit (1880-1918)," The Macmillan Dictionary of Women's Biography, London: Macmillan, 1982.