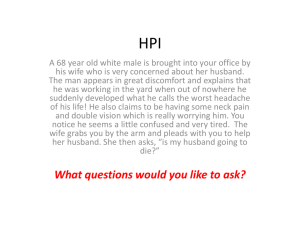

Case Presentation

advertisement

Case Presentation NSS SGD Ontok.Rodriguez.Salongcay.Samson.Bautista General Data T.A. 43 year old female Laguna Right-handed Married Roman Catholic Beautician in Brunei Date of admission: October 6, 2009 On her 8th hospital day Source of History Informant: patient Reliability: good Chief Complaint Headache History of Present Illness Patient is apparently well, with no known co-morbidity. 2 months PTA, while cleaning the toilet (+) Headache – VAS 10/10, sudden onset, fronto-parietal area, throbbing, non-radiating (+) Weakness and numbness – both lower extremities (+) Loss of consciousness – lasted for 3 days allegedly (+) Diaphoresis (-) Nausea / Vomiting History of Present Illness admitted at local hospital in Brunei Blood pressure was 160 / 100 mmHg CT scan - subarachnoid hemorrhage - Right PCOM aneurysm, infundibular type Nimodipine 60 mg x 21 days, other meds unrecalled History of Present Illness advised surgery for clipping of aneurysm - deferred Preferred to be further treated in the Philippines Patient allegedly discharged with normal neurologic findings Patient admitted at PGH for further management Review of Systems (-) fever, weight loss, anorexia (-) dyspnea, cough, colds (-) palpitations, chest pain, easy fatigability (-) abdominal pain, mass, tenderness, bowel movement changes (-) dysuria, hematuria, tea-colored urine (-) muscle or joint pain, tenderness, swelling Past Medical History (-) Diabetes mellitus (-) Tuberculosis (-) Cardiovascular disease (-) Bronchial asthma (-) Allergy to food or medication (-) Connective tissue disease (-) Substance abuse (-) Previous surgical operations or hospitalizations Family History (-) similar illness (+) Hypertension – mother (+) Stroke – uncle, maternal side (-) Diabetes mellitus (-) Tuberculosis (-) Cardiovascular disease (-) Bronchial asthma (-) Allergy to food or medication (-) Connective tissue disease (-) Substance abuse Personal and Social History Vocational course graduate Works as a beautician in Brunei Married with 2 children Denies use of cigarette, alcoholic beverage, or illicit drugs Eats fatty, salty, and sweet foods regularly No regular physical exercise Physical Examination General Survey: Patient is awake, coherent, ambulatory and not in cardiorespiratory distress Vital Signs: BP 130/90 mmHg HR 90 beats/min RR 20 breaths/min T 37.3˚C Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat: Pink palpebral conjunctivae, anicteric sclerae, (-) anterior neck mass, (-) cervical lymphadenopathy, (-) neck vein engorgement, (-) bruits Chest/Lungs: Equal chest expansion, clear breath sounds, (-) rales, (-) crackles, (-) wheezes Cardiovascular: Adynamic precordium, distinct heart sounds, normal rate, regular rhythm, (-) murmurs Abdomen: Flat, normoactive bowel sounds, soft, (-) masses or tenderness Genitourinary: Deferred Skin/Extremities: Pink nail beds, full and equal pulses, (-) cyanosis, (-) edema, (-) clubbing, (-) skin lesion Physical Examination Neurologic: GCS 15 (E4 V5 M6) Patient presently awake, conversant, oriented to time, place and person Physical Examination Neurologic: Cranial Nerves I – can smell II – can read fine print III – pupils 3 mm, equally briskly reactive to light; EOM’s full and equal IV – EOM’s full and equal V – can clench jaw, intact light touch sensation on face, brisk corneal reflex VI – EOM’s full and equal VII – can raise eyebrow, smile, frown, (-) facial asymmetry VIII – can hear grossly IX – symmetrical uvula and soft palate, (+) gag reflex X – can taste, (+) gag reflex XI – good shoulder shrug XII – tongue midline Physical Examination Neurologic: Sensory – intact light touch, temperature, vibration, pain sensation Motor - Muscle strength 5/5 in all extremities Deep tendon reflex ++ (triceps, biceps, brachioradialis, patella, Achilles’) Cerebellar – (-) dysdiadochokenisia, dysmetria, nystagmus, tandem walk, heel-to-shin test (-) Brudzinski sign, Kernig’s sign, nuchal rigidity Summary of hx and PE This is a case of a 43 year old female with no known comorbidity presenting with acute onset of severe headache, bilateral lower extremity weakness and numbness, loss of consciousness for three days, allegedly resolving after several days. Physical examination upon admission revealed essentially normal systemic and neurologic findings. CT scan Differentials Differentials Intracranial Hemorrhage (Subarachnoid Hemorrhage) - Rule In - Acute onset - Severe headache - Focal neurologic deficits - Loss of consciousness - Patient’s age - Patient is hypertensive - Family history of stroke - Patient’s diet preferences (increased cholesterol) - Patient was doing household chores during onset - Rule Out - Cannot be ruled out Differentials Ischemic Stroke Rule In Acute onset Focal neurologic deficits Patient’s age Family history of stroke - Patient’s diet preferences – fatty, salty and sweet foods Rule Out Cannot be completely ruled out (without CT Scan) Differentials Brain Tumor Rule In Headache Focal neurologic deficits Rule Out Onset of symptoms is acute Differentials Brain Abscess Rule In Headache Focal neurologic deficits Rule Out Onset of symptoms is acute No evidence of infection (afebrile, no cough/colds, no previous head surgery, etc.) Differentials Migraine Rule In Headache Patient’s sex Rule Out First episode No perceived “aura” prior to onset Focal neurologic deficits rarely occurs with migraine Assessment Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Course in the Wards Course in the Wards 10/6/09 S> Patient admitted at ACU ER. Patient seen by the treatment officer, (+) HA, VAS 2/10 fronto-temporal.(-) fever, coughs, dyspnea, chest pains, epigastric pain, urinary or bowel changes O> BP: 120/70 HR: 80 RR: 20 E/N systemic PE findings Neuro Exam : intact cranial nerves, (-) sensory and motor deficits, (-) cerebellar/ meningeal signs CT scan: A> SAH P>Dx: Blood typing, CBC, Blood Chem, CT scan (plain and with contrast) TX:Tramadol 50mg/cap q8 prn for HA, Captopril 2mg TID, Lactulose 30cc HS Patient was referred to Neurology Course in the Wards 10/07/09 S> Seen by the Neurology service.No new symptoms/ complaints, no neurological deficits. (-) headache, () dizziness, (-) nausea, (-) vomiting, (-) nape pain (-) blurring of vision O> BP: 120/80 HR: 80 RR: 20 E/N systemic PE findings Neuro Exam : intact cranial nerves, (-) sensory and motor deficits, (-) cerabellar/ meningeal sigins A> SAH secondary to cerebral aneurysm P> For repeat 4V angiography Patient transferred to NSS WOF: decrease in sensorium, severe headache,seizures, new onset neurological deficits Course in the Wards 10/09/09 S> Patient admitted at W6B17. (-) headache, (-) dizziness, (-) nausea, (-) vomiting, (-) nape pain. No other neurologic complaint. O> BP: 120/70 HR: 80 RR: 20 E/N systemic PE findings Neuro Exam : intact cranial nerves, (-) sensory and motor deficits, (-) cerebellar/ meningeal signs A> SAH P> Tx: Tramadol 50mg/cap was shifted to Etorocoxib 120mg/tab For 4V angiography For possible craniotomy, clipping of the aneurysm Course in the Wards 10/10/09 S> Patient had headache, VAS 5/10 (fronto-temporal), (+) nape pain, (+) dipahoresis, (+) vomiting (3x, non-bloody, non bilous, non-mucoid, about 3 tablespoons per episode), (+) chest pain, non radiating, ‘described as mabigat’ , (point tenderness) O> BP: 140/90 HR: 105 RR: 20 Neuro Exam : intact cranial nerves, (-) sensory and motor deficits, (-) cerabellar/ meningeal signs A> t/c costohondritis r/o ACE P> for stat ECG for Na, K, Cl Encourage deep breathings Captopril 20mg/tab BID Etoricoxib 120mg/tab for headache Referred to Gen MeD Course in the Wards 10/11/09 S> Patient seen by Gen Med. At that time (-) chest pain, (-) headache,(-) blurring of vision, (-)nape pain, (-) nausea, (-)vomiting, (-)fever, (+) palpitations 0> BP 90/60 HR 100 RR 20 E/N systemic PE findings Neuro Exam : intact cranial nerves, (-) sensory and motor deficits, (-) cerabellar/ meningeal signs ECG: ST, NA, NSSTTWC A> SAH Hypertension most probably secondary (reactive) Chest pain not anginal P> Suggest decrease Captopril to ½ tab for BP >160/100 Course in the Wards 10/12/09 S> Patient seen by SAPOD for clearance for 4v angiography and possible clipping of the aneurysm. (-) chest pain, (-) headache, (-)nape pain, (-) nause, (-)vomiting, (-)fever, (+) palpitations, (-) orthopnea, (-) PND, (-) exertional dyspnea O> > BP: 120/70 HR: 80 RR: 20 E/N systemic PE findings Neuro Exam : intact cranial nerves, (-) sensory and motor deficits, (-) cerabellar/ meningeal signs A> SAH Hypertension St. II P> Shift Captopril to Metoprolol 50mg/tab, ½ tab BID LABS ECG: ST, NA, NSSTTWC PT 11.8/11.6/>1.0/ 1.10 APTT/ 35.5/30.9 Blood Chemis try : FBS: 5.81 BUN 3.34 Crea: 6.4 Hemoglobin: 123 Hematocrit: 0.38 WBC:5.7 Platelet : 302 Na: 141 K: 3.6 Subarachnoid hemorrhage Discussion RELEVANT ANATOMY saccular aneurysms - bifurcations of vessels of circle of Willis. Circle of Willis • close proximity to ventral surface of diencephalon • adjacent to optic nerves and tracts. • important anastomosis for the 4 arteries that supply the brain - 2 vertebral and the 2 internal carotid arteries • divided into anterior and posterior sections Anterior portion of the circle of Willis • Consists of: 1. internal carotid arteries 2. anterior cerebral artery 3. anterior communicating artery Posterior portion of the circle of Willis • consists of: 1. posterior cerebral arteries 2. posterior communicating arteries, paired Location of aneurysm rupture anterior circulation - 85% of saccular aneurysms most common sites of rupture are as follows: 1. internal carotid artery, including posterior communicating junction (41%) 2. anterior communicating artery/ anterior cerebral artery (34%) 3. middle cerebral artery (20%) 4. vertebral-basilar arteries (4%) 5. other arteries (1%) Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION DEFINITION: extravasation of blood into the subarachnoid space between the pial and arachnoid membranes detrimental effect on both local and global brain function and leads to high morbidity and mortality rates. Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION Subarachnoid hemorrhage: 1. Traumatic: head trauma 2. Non-traumatic (spontaneous): a. ruptured cerebral aneurysm b. arteriovenous malformation (AVM) Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION FREQUENCY Age • Incidence increases with age • peaks at age 50 years • 80% of SAH cases: 40-65 years Sex • women to men ratio (3:2) • risk of SAH from aneurysmal rupture - maternal deaths in pregnancy • AVM rupture during pregnancy. Race • different ethnic groups develop intracranial aneurysms Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION ETIOLOGY Nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) - caused by extravasation of blood from abnormal blood vessels onto the surface of brain - result of: 1. aneurysmal ("berry," or saccular) 2. AVM leakage or rupture – 10 % Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION Less common causes of SAH: • Fusiform and mycotic aneurysms • Fibromuscular dysplasia • Blood dyscrasias • Moyamoya disease • Infection • Neoplasm • Trauma (fracture at the base of the skull leading to internal carotid aneurysm) • Amyloid angiopathy (especially in elderly people) • Vasculitis • Idiopathic SAH Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION Etiology Of Cerebral Aneurysms - unknown Congenital defects in the muscle and elastic tissue of the arterial media in the vessels of the circle of Willis • familial cerebral aneurysm - 10% • multiple aneurysms in patients with SAH 15% • congenital diseases coarctation of the aorta Marfan syndrome Ehlers-Danlos syndrome fibromuscular dysplasia polycystic kidney disease Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION Aneurysmal formation - Acquired factors Atherosclerosis Hypertension Hemodynamic stress Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION RISK FACTORS Smoking heavy alcohol consumption hypertension and SAH – conflicting evidence hypertension has been identified as a risk factor for aneurysm formation, the data with respect to rupture are conflicting hypertensive states (stimulants e.g. cocaine) - promote aneurysm growth and earlier rupture Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION The following do not appear to be significant risk factors for SAH: • Use of oral contraceptives • Hormone replacement therapy • Hypercholesterolemia • Vigorous physical activity • The risk of AVM rupture is greater during pregnancy Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION PATHOPHYSIOLOGY • Aneurysms - occur at branching sites on large cerebral arteries of circle of Willis. defects in media of arteries small outpouchings ↓ expand due to hydrostatic pressure 1. pulsatile blood flow 2. blood turbulence (greatest at the arterial bifurcations) ↓ mature aneurysm paucity of media replaced by connective tissue diminished or absent elastic lamina Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION Law of La Place: ‘tension is determined by the radius of the aneurysm and the pressure gradient across the wall of the aneurysm’ probability of rupture ~ aneurysm wall tension Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION rate of rupture is directly related to the size of the aneurysm < 5 mm diameter - 2% risk of rupture 6-10 mm diameter - 40% risk of rupture Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION aneurysm ruptures ↓ blood extravasation (under high arterial pressure) ↓ 1. local tissue damage 2. global increase in intracranial pressure (ICP) 3. meningeal irritation Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION PRESENTATION signs and symptoms: subtle prodromal events to classic presentation of catastrophic headache clinical history physical examination - neurologic examination Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION Cause of prodromal signs and symptoms: 1. sentinel leaks 2. mass effect of aneurysm expansion 3. emboli Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION 1. Sentinel (‘warning’) leaks • produce minor blood leakage • symptoms: head pain - sudden focal or generalized, severe nausea, vomiting photophobia malaise neck pain • not elevated ICP • not in setting of AVM Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION 2. Mass effect • characteristic features based upon aneurysm location. a. Posterior communicating artery/internal carotid artery Focal, progressive retro-orbital headaches oculomotor nerve palsy (Just posterior and superior to the cavernous sinus, the oculomotor nerve crosses the terminal portion of the internal carotid artery at its junction with the posterior communicating artery.) b. Middle cerebral artery Contralateral face or hand paresis aphasia (left side) contralateral visual neglect (right side) c. Anterior communicating artery Bilateral leg paresis bilateral Babinski sign d. Basilar artery apex Vertical gaze, paresis, and coma e. Intracranial vertebral artery/posterior inferior cerebellar artery Vertigo, components of lateral medullary syndrome Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION 3. Emboli: transient ischemic attacks from intra-aneurysmal thrombus formation. classic symptoms and signs of aneurysmal rupture: Headache - sudden onset, severe, ‘worst headache of my life’ Nausea, vomiting meningeal irritation nuchal rigidity and pain back pain bilateral leg pain Photophobia and visual changes sudden loss of consciousness (LOC) Transient or comatose for several days Seizures Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION Physical Examination Findings normal or consistent with the following: a. Focal neurologic abnormalities - hemiparesis, aphasia, hemineglect, cranial nerve palsies, and memory loss b. Motor neurologic deficits - middle cerebral artery aneurysms c. Ophthalmologic examination - subhyaloid retinal hemorrhages, papilledema d. Blood pressure elevation e. Temperature elevation - chemical meningitis from subarachnoid blood products f. Tachycardia Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION CLINICAL GRADING SCALES • Clinical scales: 1. Hunt and Hess grading system 2. World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) grading system • Imaging scale: Fischer scale CT scan appearance subarachnoid blood quantification Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION HUNT AND HESS GRADING SYSTEM Grade 1 Asymptomatic or mild headache Grade 2 Moderate-to-severe headache, nuchal rigidity, and no neurological deficit other than possible cranial nerve palsy Grade 3 Mild alteration in mental status (confusion, lethargy), mild focal neurological deficit Grade 4 Stupor and/or hemiparesis Grade 5 Comatose and/or decerebrate rigidity Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION WFNS SCALE Grade 1 Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 15, motor deficit absent Grade 2 GCS of 13-14, motor deficit absent Grade 3 GCS of 13-14, motor deficit present Grade 4 GCS of 7-12, motor deficit absent or present Grade 5 GCS of 3-6, motor deficit absent or present Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION FISCHER SCALE (CT SCAN APPEARANCE) Grade 1 No blood detected Grade 2 Diffuse deposition of subarachnoid blood, no clots, and no layers of blood greater than 1 mm Grade 3 Localized clots and/or vertical layers of blood 1 mm or greater in thickness Grade 4 Diffuse or no subarachnoid blood, but intracerebral or intraventricular clots are present Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION Hunt and Hess and WFNS grading systems - correlation with patient outcome. Fischer classification - predict likelihood of symptomatic cerebral vasospasm, All 3 grading systems are useful in determining the indications for and timing of surgical management. Subarachnoid hemorrhage DISCUSSION ‘For an accurate assessment of SAH severity, these grading systems must be used in concert with the patient's overall general medical condition and the location and size of the ruptured aneurysm.’ Management Work-up Work-up CBC count - For evaluation of possible infection or hematologic abnormality Prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) - For evaluation of possible coagulopathy Serum electrolytes - To establish a baseline for detection of future complications Blood type and screen - In case intraoperative transfusion is required or in the setting of massive hemorrhage Cardiac enzymes - For evaluation of possible myocardial ischemia Arterial blood gas (ABG) - Assessment is necessary in cases with pulmonary compromise Imaging CT scan: The diagnosis of SAH usually depends on a high index of clinical suspicion combined with radiographic confirmation via CT scan without contrast. CT scan has a sensitivity of 98% within the first 12 hours of the ictus and 93% within 24 hours; sensitivity decreases to approximately 80% at 72 hours and 50% at 1 week. CT scan findings are positive in 92% of patients who have SAH. Lumbar Puncture LP should be performed when strong clinical suspicion of SAH exists with a negative finding on CT scan or when a CT scan is not available. If possible, a CT scan should be performed before LP to exclude significant intracranial mass effect, elevated ICP, obstructive hydrocephalus, or obvious intracranial bleed. LP findings often are negative within 2 hours of the ictus, and LP is most sensitive 12 hours after the bleed. Lumbar Puncture LP should not be performed if the CT scan demonstrates an SAH because of the (small) risk of further intracranial bleeding associated with a drop in ICP. SAH often can be distinguished from traumatic LP by comparing the red blood cell count of the first and last tubes of CSF. The RBC count usually will not decrease between the first and last tubes in the setting of SAH; however, case reports of this phenomenon do exist. The most reliable method of differentiating SAH from a traumatic tap is to spin down the CSF and examine the supernatant fluid for the presence of xanthochromia, a pink or yellow coloration of the CSF supernatant caused by the breakdown of RBCs and subsequent release of heme pigments. Cerebral angiography Cerebral angiography is particularly useful in cases of diagnostic uncertainty Cerebral angiography can provide the following important surgical information in the setting of SAH: Cerebrovascular anatomy Aneurysm location and source of bleeding Aneurysm size and shape, as well as orientation of the aneurysm dome and neck Relation of the aneurysm to the parent artery and perforating arteries Presence of multiple or mirror aneurysms (identically placed aneurysms in both the left and right circulations) Medical Therapy Medical therapy The initial management of patients with SAH is directed at patient stabilization. Assess the level of consciousness and airway, as well as breathing and circulation (ABCs). Endotracheal intubation should be performed for patients presenting with coma, depressed level of consciousness, inability to protect their airway, or increased ICP. Medical therapy Therapeutic goals of subarachnoid hemorrhage: 1. blood pressure control 2. prevention of seizures 3. treatment of nausea 4. management of ICP 5. prevention of vasospasm 6. control of pain 7. maintenance of cerebral perfusion Medical therapy The traditional treatment of ruptured cerebral aneurysms included strict blood pressure control, with fluid restriction and antihypertensive therapy. This approach was associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality from the ischemic complications of hypovolemia and hypotension. Medical therapy The current recommendations advocate the use of antihypertensive agents when the mean arterial pressure (MAP) exceeds 130 mm Hg. Intravenous beta-blockers, which have a relatively short half- life, can be titrated easily and do not increase ICP. Beta-blockers are the agents of choice in patients without contraindications. Medical therapy Calcium channel blocker calcium - involved in the generation of the action potential. calcium channel blockers - inhibit movement of calcium ions across the cell membrane, depressing both impulse formation (automaticity) and conduction velocity. Nimodipine (Nimotop) - 60 mg PO q4h x 21 d For improvement of neurological impairments resulting from spasms following SAH caused by ruptured congenital intracranial aneurysm in patients who are in good postictal neurological condition. Medical therapy therapeutic interventions for increased ICP include the following: • Osmotic agents (eg, mannitol), which can decrease ICP dramatically (50% after 30 min postadministration) • Loop diuretics (eg, furosemide) also can decrease ICP • The use of IV steroids (eg, Decadron) is controversial but is recommended by some authors. Prophylaxis and treatment of complications Common complications of SAH: Rebleeding Vasospasm Hydrocephalus Hyponatremia Seizures Pulmonary complications Cardiac complications Rebleeding Rebleeding is the most dreaded early complication of SAH. The greatest risk of rebleeding occurs within the first 24 hours of rupture (4.1%). The cumulative risk of rebleeding is 19% at 14 days. The overall mortality rate from rebleeding is reported to be as high as 78%. Measures to prevent rebleeding Bedrest Analgesia. Pain is associated with a transient elevation in blood pressure and increased risk of rebleeding. Sedation Stool softeners Antifibrinolytics have been shown to reduce the occurrence of rebleeding. However, outcome likely does not improve because of a concurrent increase in the incidence of cerebral ischemia. Vasospasm Cerebral vasospasm, the delayed narrowing of the large capacitance vessels at the base of the brain leading cause of morbidity and mortality in survivors of nontraumatic SAH. Vasospasm is reported to occur in as many as 70% of patients with SAH and is clinically symptomatic in as many as 30% of patients. Most commonly, this occurs 4-14 days after the hemorrhage. Risk factors for vasospasm Larger volumes of blood in the subarachnoid space Clinically severe SAH Female sex Young age Smoking Measures used for prevention of vasospasm Maintenance of normovolemia, normothermia, and normal oxygenation are paramount to vasospasm prophylaxis. Volume status should be monitored closely Prophylaxis with oral nimodipine: Calcium channel blockers have been shown to reduce the incidence of ischemic neurological deficits nimodipine has been shown to improve overall outcome within 3 months of aneurysmal SAH Measures used for prevention of vasospasm Some evidence indicates that subarachnoid clot removal achieved via intracisternal injections of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rTPA) may dramatically reduce the risk of vasospasm. Aspiration and irrigation of the subarachnoid clot at the time of aneurysmal clipping associated with a significant risk of iatrogenic trauma to pial surfaces and small vessels. Surgical therapy Surgical Clipping introduced by Walter Dandy of the Johns Hopshins Hospital in 1937. It consists of performing a craniotomy, exposing the aneurysm, and closing the base of the aneurysm with a clip. The aneurysmal neck is obliterated via application of a clip that occludes blood flow to the aneurysmal dome without compromising flow to the parent artery. Surgical Clipping Surgical clipping has a lower rate of aneurysm recurrence after treatment. Direct aneurysmal clipping is still considered first-line treatment in the United States. Clips are available in various sizes and shapes. Endovascular coiling Endovascular coiling was introduced by Guido Guglielmi at UCLA in 1991. It consists of passing a catheter into the femoral artery in the groin, through the aorta, into the brain arteries, and finally into the aneurysm itself. Once the catheter is in the aneurysm, platinum coils are pushed into the aneurysm and released. These coils initiate a clotting or thrombotic reaction within the aneurysm that, if successful, will eliminate the aneurysm. Endovascular coiling Guglielmi detachable coil system (GDC) is the first-line therapy in Europe. They are soft, flexible, and can be contoured to the configuration of the aneurysm. Sizes range from 2-20 mm in diameter and 2-30 cm in length. In limited clinical trials, GDCs have been reported to achieve excellent rates of aneurysmal occlusion combined with a low complication rate in appropriate patients. Surgical clipping vs. Endovascular coiling the risks associated with surgical clipping and endovascular coiling, in terms of stroke or death from the procedure, are the same . The major problem associated with endovascular coiling is a higher aneurysm recurrence rate. Although endovascular coiling is associated with a shorter recovery period as compared to surgical clipping, it is also associated with a significantly higher recurrence rate after treatment. Other surgical options Proximal ligation of the parent artery or trapping of aneurysms with or without bypass. Proximal ligation is effective for giant aneurysms. Wrapping or coating of aneurysms may be the only option in rare cases of dissecting or fusiform aneurysms Timing of surgical intervention Advantages of early surgery (0-3 d) : Prevention of rebleeding, which is associated with a high mortality rate Possible prophylaxis against vasospasm by removal of subarachnoid clot Prevention and treatment of ischemic complications Prevention of medical complications Decreased duration of hospitalization Timing of surgical intervention Disadvantages of early surgery for SAH : Technical problems associated with edematous brain tissue High risk of intraoperative rupture of fragile aneurysm Higher surgical morbidity and mortality rates Timing of surgical intervention Advantages of delayed surgery for SAH (>10 d posthemorrhage) Brain tissue is less edematous. Lower risk of intraoperative aneurysm rupture Lower surgical morbidity and mortality rates Flexibility of scheduling The disadvantages of delayed surgery: Increased rate of morbidity and mortality due to rebleeding Technical difficulties due to adhesions around the aneurysm Complications of surgical clipping Hemorrhagic complications Ischemic complications Damage to parent artery or perforating arteries Acute or delayed neurological deficits from iatrogenic trauma Meningitis Cellulitis and wound infection Nonspecific postsurgical syndrome similar to postconcussive syndrome Common complications of endovascular therapy Aneurysm rupture (GDCs, balloons) Thromboembolism (GDCs) with acute or delayed neurologic deficit Balloon rupture or deflation Prognosis Despite advances in medical and surgical therapy, the mortality rate for aneurysmal SAH remains 50% at 1 year. Survival is inversely proportional to SAH grade upon presentation. Hunt and Hess Grading and Survival Rate Grade 1 – 70% Grade 2 – 60% Grade 3 – 50% Grade 4 – 20% Grade 5 – 10% Prognosis Approximately 25% of survivors have persistent neurologic deficits. Most survivors have either a transient or a permanent cognitive deficit. Mortality and morbidity are influenced by: magnitude of the bleed age of the patient co-morbid conditions medical complications. Sentinel Headache and the Risk of Rebleeding After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Stroke, Journal of the American Heart Association (Sep 28, 2008) INTRODUCTION The presence of a severe, sudden headache, often referred to as a warning leak, minor leak, or sentinel headache (SH), during the days or weeks before subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) has been reported in 15% to 60% of all patients eventually admitted with an SAH Pathophysiology of an SH: changes in the wall of the aneurysm without rupture or rupture of an intracranial aneurysm causing minor SAH INTRODUCTION The current mainstay of treatment of acute SAH consists of prevention of another bleed, because the rebleeding rate and associated mortality are exceedingly high Most protocols favor early treatment in 48 to 72 hours after the ictus INTRODUCTION Because the rebleeding rate may be highest immediately after SAH, some investigators have suggested a general policy of “ultraearly” surgery, which is unlikely to gain wide acceptance, because it does not provide treatment with the best team under the optimum circumstances for many patients INTRODUCTION It would be of important clinical value to identify a subgroup of patients that is more likely than others to experience rebleeding The hypothesis of this study was that there is a causal relation between the aneurysm or SAH and the clinical sign of an SH; ie, patients with an SH may have more fragile aneurysms INTRODUCTION This hypothesis was prospectively tested by investigating whether patients who presented with an SH before the index SAH indeed had a higher rate of rebleeding compared with those without an SH SUBJECTS AND METHODS Patient Population 237 consecutive patients with SAH proven by computed tomography (CT) or lumbar puncture Patient characteristics, treatment, radiological features, the presence of an SH, and rebleeding, was prospectively entered in an SPSS database SUBJECTS AND METHODS General Patient Management Early surgery strategy (24 to 48 hours) was done in patients of all clinical grades unless the patients were hemodynamically unstable or moribund Routine surveillance included daily transcranial Doppler measurements and, in selected cases, multimodal monitoring of brain tissue O2, regional cerebral blood flow, and interstitial metabolites SUBJECTS AND METHODS General Patient Management All patients received Nimodipine from the day of admission Fludrocortisone was administered as an adjunct in case of hyponatremia Desmopressin was used to control excessive diuresis Outcome was assessed according to a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) after 6 months SUBJECTS AND METHODS Sentinel Headache Thorough history was taken of patients, relatives, accompanying persons, general practitioners, and emergency or admitting doctors Inquired about a sudden, severe headache of unknown character and intensity lasting at least 1 hour in the last 4 weeks before the index SAH that had never been experienced before There had to have been an improvement before the index SAH or another deterioration that led to a diagnosis of SAH SUBJECTS AND METHODS Rebleeding Only included CT-proven episodes of rebleeding (neuroradiologist was blinded to a history of SH) Cases with a high clinical suspicion of rebleeding but without confirmation by at least 2 subsequent CT scans were not included SUBJECTS AND METHODS Rebleeding All patients underwent CT scanning after clipping/intervention within 48 hours as well as at day 14 or at discharge Rebleeding after aneurysm obliteration was not included SUBJECTS AND METHODS Data Analysis To test for an association with rebleeding, categorical variables were tested with Fisher exact test or x2 test Continuous variables were subjected to the Mann-Whitney U test or a t-test Binary logistic-regression model for the prediction of rebleeding was used to find the most important baseline predictors Results with P<0.05 were considered statistically significant RESULTS Patient Population RESULTS Rebleeding Overall rebleeding rate - 9.7% (23 of 237) SH before the index SAH - 17.3% (41 of 237) Univariate analysis revealed that the presence of an SH, maximum aneurysm size, and the number of aneurysms an individual patient presented with were significantly associated with rebleeding RESULTS Rebleeding Trend for an association with less rebleeding for aneurysms of the anterior circulation No association between the frequency of rebleeding and patient age, sex, smoking habits, or findings on the initial CT scan RESULTS Rebleeding The odds of eventually experiencing a rebleeding episode for a patient with an SH compared with a patient without an SH was 13.6 (P<0.0001) in the univariate model RESULTS Rebleeding Relative risk was 9.0 Sensitivity was 65.2% Specificity 87.9% Positive predictive value was 36.6% Negative predictive value was 95.9% RESULTS Rebleeding In a binary logistic-regression model,the presence of an SH remained a very statistically significant and independent predictor of rebleeding after controlling for age, aneurysm size, number of aneurysms, and the time at risk RESULTS Outcome Overall outcome at 6 months was available for 212 patients Rebleeding significantly increased the odds of death, reduced the odds of survival with good outcome, and reduced the odds of survival with functional independence RESULTS Outcome CONCLUSION The presence of an SH is strongly related to an increased frequency of rebleeding before aneurysm obliteration Therefore, a history of SH might be used to identify a subgroup of patients with a high risk for rebleeding and who could benefit from ultraearly aneurysm obliteration or immediate clot-stabilizing drug treatment Thank you vey much!!!!! Block_U_lala